Jeremiah

Thunderstruck. Dazed. Speechless. Flabbergasted.

I could go on and on with words to describe the astonishment I felt upon hearing the news. But, first, let me give you a brief description of my background. I was a single woman, living alone, with only my books to keep me company. Writing took up most of my waking hours; reading took up the rest. To sum up my life: I was happy. I had a successful career, a home I loved and a life I cherished. That is until I woke up one morning in early April of 1984.

It started out no differently than most other mornings, with the sunlight streaming through my bedroom window. There was no need for an alarm clock to wake me at a given hour since my life did not adhere to a set schedule. After getting out of bed, I put on my robe and slippers and headed to the kitchen where I made myself a cup of coffee.

As I sat in the breakfast nook reading Stephen King's latest novel, Pet Sematary, I had no premonition of what was to come. How could I? When my parents divorced, I was only five years old. I remained with my mother, and my brother went to live with my father. Price Symington. That was my sibling's name. All I remember about him was that he was two years older than I was and that he had blue eyes and blond hair, but it could have darkened over the years. Other than Christmas and birthday cards, I had no contact with either my father or brother after the divorce. Then, six years after my parents split up, even these Hallmark greetings stopped coming.

In all honesty, I rarely thought about the male members of my family. The last time either of them came to mind was when my mother died. At that time, I had the good intention of finding Price to let him know of her passing, but when all my attempts to locate him failed, I gave up the pursuit. That was nearly eight years earlier.

Thus, on that April morning, as I sat in my breakfast nook with my novel and cup of coffee, I had no idea that the last surviving member of my family (besides myself, of course) was taking his last breath in a hospital in Switzerland. I would not receive the transatlantic telephone call from Wolfgang Hagelin, Price's lawyer, for several hours. I poured myself a second cup of coffee and continued to read in blissful ignorance.

Had I known what was about to befall me, would I have spent that time differently? Probably not.

* * *

Shocked. Stupefied. Astounded. Bewildered.

These synonyms flitted across my mind, making me feel like a living, breathing thesaurus. As an avid reader, I acquired an extensive vocabulary that, as a writer, I put to good use. I also found words comforting. In times of sorrow or stress, I relied upon them to chase away the fear and self-doubt that often plague the human brain.

If there was ever a time when I needed the solace of my words, it was when I stepped off the airplane in Zurich and was whisked away in a limousine to attend the funeral of a brother I had not seen since I was five years old. Wolfgang Hagelin met me at the airport. Dressed in an Armani suit, the good-looking, silver-haired, blue-eyed attorney made quite an impression.

"I'm sorry for your loss," he said in flawless English.

"Thank you," I replied. "I don't really know what to say or do. This was all so sudden."

"I've taken care of all the arrangements. I assume you have no objections to your brother's body being buried here in Switzerland."

"No. None at all."

I certainly had no intention of bringing it back to America when I returned home.

"Feel free to ask me any questions you might have," Wolfgang offered.

"Where is the service to be held?"

"Not far from where your brother was living."

"In a church?"

"No, Mr. Symington did not have any religious affiliations."

"Oh? I'm afraid I know very little about him. Our parents split up when we were young. Speaking of my parents, will my father be at the service?"

"You really have been out of touch with your family," the lawyer observed. "Your father passed away more than ten years ago."

There was no need to mentally recite a list of synonyms over this piece of news. I simply accepted it with as much emotion as one would exhibit when listening to a weather forecast. My lack of feeling does not make me callous or cold-hearted. It is only that my father was a stranger to me. Even when he and my mother were still living together, I saw very little of him. I could not, in all honesty, remember a single thing about him.

"Was my brother married?" I asked.

"Once, but his wife ... she's gone, too."

"Gone as in she left him or gone as in 'Elvis has left the building' gone."

A fleeting look of displeasure appeared on Herr Hagelin's face: a narrowing of the eyes and a tightening of the lips.

"I'm sorry," I quickly apologized. "I don't mean to sound flippant. The news about Price and this unexpected trip to Switzerland have knocked me for a loop."

"I understand, Miss Symington. Why don't we discuss your brother's family after the life celebration is concluded?"

Life celebration. Was that the latest thing? Whatever happened to good, old-fashioned funerals? If I were the one who permanently checked out, I would want an Irish wake. Throw open the windows, light the candles, stop the clocks, turn on the music and pass around the food and booze. But that's me, and I'm still alive.

As we continued our drive, we both lapsed into silence. I turned my face toward the tinted window and tried to recall the last time I had seen my brother. Did I cry when my mother told me he was going away? I can't remember.

The limousine pulled into a parking lot. The sign above the building read BESTATTUNGSINSTITUT. It was the German word for funeral parlor, the lawyer explained. Yves Fontenot, a middle-aged man who looked more suited to lederhosen than a Burberry suit, greeted us.

"I am the life celebrant," he explained.

Life celebrant? Is that like a mortician, a funeral director or an undertaker? What is this brave new world I've been thrust into?

When I walked into the bestattungsinstitut, the first thing I noticed was the three-foot-high photograph placed on an easel beside the casket. (Is it still called a casket or coffin or has it been renamed to something less morbid? An eternal rest chamber perhaps?) The man in the photograph had blue eyes and hair that was still blond. Had I seen the photo out of context, I would not have known who he was since there was no family resemblance—at least none that I could see.

For the next two and a half hours, I sat through my brother's celebration of life service. More than thirty people stood up and shared stories about him. Most spoke in English—probably for my benefit—but there were a few who spoke in German or French. Finally, when the last person sat down, all eyes turned in my direction.

"Is there a memory you would like to share with us, Georgia?" Yves Fontenot asked.

I froze. What could I say? That the man lying in the casket was a stranger to me? No, I had to tell them something. I rose from my seat, stood on wobbling legs and began to speak.

"One year for Christmas my brother gave me a doll. It wasn't a Barbie or any of the other popular dolls little girls like me asked Santa to bring them. It was a plain doll made of cloth. She wore a red dress with a white collar and gold buttons. She had yellow yarn for hair, which was put into two pigtails held together with red ribbons."

I looked around the room and saw that people were following my every word.

"My friends all laughed when they saw that doll. Santa had brought them store-bought fashion dolls with multiple outfits or baby dolls that could talk, cry and even wet their diapers. My doll did nothing. She could not even open and close her eyes because they were painted onto her face. But I loved her, for my brother had picked it out himself and paid for it with his own money. To this day, I still have that doll. She sits in a place of honor on a shelf in my home office, along with my writing awards. Even though her face is stained, her dress has worn thin in spots and her yellow wool hair has seen better days, it still means a great deal to me. And now that Price is gone I shall treasure it even more."

My words were rewarded with applause. Several of the people in the audience wiped tears from their eyes.

Damn, I'm good! (If I do say so myself.) That is why I'm a successful writer. I can make up a believable story on the spur of the moment.

My dearly departed brother never got me anything for Christmas.

* * *

Stunned. Dumbfounded. Astonished. Confounded.

Thank you, my friends, if I did not have synonyms to mentally recite, I surely would have lost it.

"Why me?" I asked Herr Hagelin after he explained my late brother's last wishes.

"You are all the family Mr. Symington has left. You and Jeremiah, that is."

"But I hardly knew my brother, and I didn't even know Jeremiah existed until now."

"Nonetheless, your brother named you as his son's legal guardian in his will."

Again, my brain took refuge in mentally reciting words; however, they mostly consisted of four letters and were not fit for young ears or mixed company.

"What am I going to do with him?" I asked. "I have no experience raising children."

"Most people don't until they actually have them."

"But he's not mine!"

"He is now. Come, let me introduce you to him."

"You mean he's here?"

"In the next room."

I was not sure what to expect. All I knew about my nephew was that he was a five-year-old orphan named Jeremiah. And now, thanks to my brother, he was my responsibility. When Wolfgang opened the door, it was as though I had stepped into H. G. Wells's time machine. Suddenly, I remembered with crystal clarity what Price had looked like because Jeremiah was the spitting image of his father at that age.

"Hello, there," I said with a tremulous voice.

The child stared at me but said nothing.

"There's something I neglected to mention," the lawyer announced.

"What's that?"

"Jeremiah doesn't speak."

"You mean he doesn't speak English?"

"No, I mean he doesn't speak at all. He's a mute."

Oh, Christ, give me strength! (You know things are bad when an agnostic calls on the Almighty for help.) Not only am I being asked to raise a child, but a special needs one to boot! Damn you, Price! How could you do this to me?

Just as I was considering running from the lawyer's office and taking the next flight back to America—alone—the cherubic little boy smiled and held out his tiny hand to shake mine.

"It's nice to meet you, Jeremiah," I said, kneeling down so that I could speak to him on his level. "I'm your Aunt Georgia. You're going to come live with me in the United States. Would you like that?"

The boy's smile widened, and he nodded his head.

* * *

Amazed. Surprised. Flummoxed. Nonplussed.

"Is this all there is? One suitcase?" I asked in disbelief when Herr Hagelin delivered my nephew to me at Zurich Airport. "Are you sending the rest of his things separately?"

"No. All his clothes are in that case. If he requires additional clothing, I'm sure the fund Mr. Symington set up for his son's care will more than cover the cost."

"It's not that. I have plenty of money. But what about his toys? When will they arrive?"

"Jeremiah doesn't play with toys."

"No cars? Action figures? A soccer ball?"

"None at all."

"Well, when we get to America, I intend to take him shopping—for clothes and toys!"

"You must keep in mind that Jeremiah is a most unusual child," the lawyer said mysteriously.

"But he's still a child, and he's my child now."

"Good luck to you, Miss Symington. And to you, Jeremiah. I hope you will like America."

It was after midnight when the plane landed at Boston's Logan Airport. After going through customs, my nephew and I retrieved our bags from the luggage carousel, after which I found my vehicle in the airport parking lot. On the drive home, I turned on the radio in my Lincoln Town Car to dispel the silence.

"I hope you like rock music," I said.

Jeremiah smiled and nodded.

We listened to the Doors, Styx, Aerosmith, the Bee Gees, the Eagles and a new band from New Jersey, Bon Jovi. The music temporarily stopped for a news update. The newscaster said something about President Reagan, but I was not interested in politics. The weather forecast, however, caught my attention. The weatherman claimed that snow was on its way—not flurries but a significant snowfall.

"It's April already, and we're still getting snowstorms. When is spring going to get here? We may have to put off our shopping trip until the weather improves," I announced. "My car isn't good in snow."

By the time I pulled into my driveway, Jeremiah had fallen asleep. At five years old, he was too heavy for me to carry, so I gently shook him awake. The angelic look that was usually present on his face was briefly replaced by a menacing one.

"I'm sorry to wake you," I apologized. "But we're home."

The angry countenance was quickly replaced by a benign one. However, the memory of the child's glaring eyes gave me a renewed cause to worry.

What was I getting myself into?

* * *

Baffled. Incredulous. Mystified. Bemused.

I was at it again. Words were racing through my mind as I stared at my nephew, unable to comprehend his unique talent.

It began the morning after we returned from Switzerland. Mother Nature had made good on the weatherman's promise by dropping eighteen inches of snow on New England. There would be no shopping trips to Jordan Marsh or Filene's. Thankfully, there were clothes in his suitcase, but there were no toys of any kind.

"Did you want to go outside and play in the snow?" I asked him.

He shook his head from side to side.

"I don't blame you. It's freezing out there, and the snow is coming down hard. Maybe there's something on television that will interest you."

I turned on PBS, which was showing Sesame Street. Jeremiah showed no interest in Big Bird or Bert and Ernie, so I changed the channel. The only cartoon I found was The Smurfs, but that did not appeal to him either.

How do I entertain a five-year-old all day? I wondered.

Suddenly, I remembered that my mother, a packrat at heart, had kept my old toys in boxes up in the attic. I doubted Jeremiah would want to play with my Barbie or Tammy dolls, but I was sure there were gender-neutral playthings up there as well. After putting on a jacket, I went upstairs. Good old mom, efficient as ever, had labeled the boxes. I grabbed one that said TOYS and lugged it downstairs.

"Maybe you can find something to play with in here," I declared.

Curious, Jeremiah watched as I cut the packing tape and opened the flaps. What followed was, to me, a memory-filled journey back to my childhood. The box contained toys I had not thought about in years but had once been treasured belongings.

"My Pebbles Flintstone doll! She was my favorite."

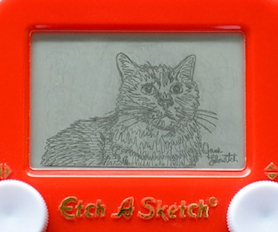

Also in the box were my Spirograph, an Easy-Bake Oven, Miss Cookie's Kitchen Colorforms, a ponytail Barbie and a flock-haired Ken (both of which had seen better days), an Etch A Sketch, a View-Master with more than a dozen reels stored in a plastic sandwich bag, a slightly bent Slinky, a Magic 8 Ball, Mr. Potato Head and two Troll dolls.

"You might like to play with this," I said, handing my nephew the Etch A Sketch. "You can draw horizontal and vertical lines using the two buttons."

Since I had never been able to master smooth diagonal lines, much less circles, the only things I ever drew were staircases and boxes. Jeremiah carried the Etch A Sketch to the living room and sat down on the couch with it. Hoping it would keep him occupied for an hour or so, I went to the office, turned on my IBM Selectric typewriter and began to work.

It took several starts and stops at writing before I was in "the zone." Once I was there, however, my fingers found it difficult to keep up with my thoughts. Rarely at a loss for words, I wrote close to twenty pages of my latest novel before my stomach alerted me to the lateness of the hour. I glanced at the clock on the wall; it was past noon. Although I often skipped meals, I now had a child to consider.

"What would you like for lunch?" I asked, momentarily forgetting that he could not speak. "A sandwich?"

Jeremiah, who was intent on creating something with the Etch A Sketch, nodded his head without taking his eyes off the screen.

"Is grilled cheese okay?"

Another nod.

At least he was not a picky eater.

Ten minutes later, I placed two sandwiches, a glass of milk and a bottle of TaB on the kitchen table.

"Lunch is ready."

As I washed the toasted cheese down with my diet cola, I wondered what I would make for dinner. I was never much of a cook and more often than not ate at a restaurant. The snow that was still falling made that option undesirable. It was time to look into the cabinets for my emergency stash: food I kept on hand for the rare time I was unable to buy a prepared meal.

"Let's see what I've got. Rice-A-Roni, Kraft Macaroni & Cheese, Bumble Bee Tuna, Ragú spaghetti sauce—that sounds good for a snowy day. Let's see if I have any pasta. Yup. Here's a box of Ronzoni."

Since lunch was done and I had everything I needed to make dinner, I decided to go back to work. As I passed by the living room couch on my way to my office, I looked down to see what Jeremiah had drawn with the Etch A Sketch. Expecting something similar to what I used to create, I was amazed to see a detailed drawing of the Statue of Liberty.

"You did this?" I asked with disbelief. "How? I couldn't draw this with a pencil, much less with an Etch A Sketch! You must be a prodigy!"

Rather than exhibit pride in his work, my nephew grabbed the toy from my hands, turned it upside down, shook it and erased the sketch. Then he handed it back to me.

"Why did you do that? It was such a beautiful drawing."

But Jeremiah did not answer. When was I going to remember that he could not speak?

* * *

Befuddled. Overwhelmed. Agape. Aghast.

That evening, after a somewhat palatable spaghetti dinner, Jeremiah continued playing with the Etch A Sketch. Since I was done writing for the day, I joined him in the living room.

"Would you like to watch anything on TV?" I asked, to which I got a shake of his head.

I took out a tape of an old James Cagney movie, popped it into my Betamax and pressed the play button. Since George M. Cohan was not one of Cagney's gangster roles, I had no reservations about watching Yankee Doodle Dandy with a child in the room. By the time Cagney, playing an elderly Cohan, danced down the White House steps after telling his life story to FDR, it was already past nine o'clock.

"It's time for bed," I announced as I turned off the VCR and television.

Jeremiah shook his head.

"It's after nine already. Bedtime."

He put the Etch A Sketch down—not before erasing the picture he drew so that I could not see it—and picked up the Magic 8 Ball that was next to him on the end table. He turned it over and handed it to me. I glanced down at the window and read the saying that was revealed: MY REPLY IS NO.

I remembered reading somewhere that of the twenty sayings featured in the fortunetelling toy, ten were affirmative, five were non-committal and five were negative. That means Jeremiah had a one in four or twenty-five percent chance of getting that answer.

"Regardless of what the Magic 8 Ball says, you're going to bed."

He grabbed the toy from my hand, shook it to get another answer and handed it back to me.

DON'T COUNT ON IT.

What were the odds of getting two negative answers in a row? I did not bother to calculate them. I majored in English, not math.

"Let's put the toys away for tonight and go to bed."

He reached for the Magic 8 Ball, but I held it away from him. Then he picked up the Etch A Sketch and furiously turned the buttons. A few minutes later, he showed me the screen. My mouth opened in surprise when I read what he had written on it: I'M NOT TIRED. LEAVE ME ALONE.

Jeremiah may be a prodigy, I realized, but he is also a brat. I made the decision at that point not to let him get away with it.

"To bed—NOW!"

He angrily pressed his lips together and glared at me, but he did as he was told. Although I had not held the Panglossian belief that becoming the boy's guardian would be easy, I did not think it would be so difficult.

The next morning, I found my nephew sitting on the couch drawing with the Etch A Sketch.

"You're up early," I said cheerfully.

There was no response from the boy: neither a movement of the head nor a glance in my direction.

"Since I don't have much food in the house, I'm going to order groceries from the market. I don't know what you normally eat for breakfast, but I'll get a dozen eggs, bread, pancake mix and maple syrup. Do you like oatmeal? I can get that, too."

There was no nod or shake of the head.

"I'm speaking to you. Do you like oatmeal?"

Jeremiah paid no attention to me.

"Are you mad because I made you go to bed last night?"

When he continued to ignore me, I leaned over and took the Etch A Sketch from him. Again, what he had drawn was no simple sketch of predominantly horizontal and vertical lines and simple geometric shapes. He had managed to create a detailed illustration of a woman lying dead on the floor, bleeding from a gunshot wound to the chest. The features on her face left little doubt as to who she was supposed to be: me.

"What's the meaning of this?" I demanded to know, forgetting once again that he could not answer me. "What made you draw such a picture?"

The look on my nephew's face was one of profound malevolence as he picked up the Magic 8 Ball, turned it over and showed me the answer in the window: I HATE YOU.

That sentiment was not now and never had been one of the twenty sayings Ideal included in its toy.

How did it get there then? I wondered.

* * *

Agog. Taken-aback. Shook up. Awestruck.

During the next several days, a cold war developed between Jeremiah and me that would rival the one that existed between the USA and the USSR. After being ignored for two days, I stopped asking him questions. I made meals and put them on the table. If he ate them, good. If not, oh well! Let him go hungry until the next mealtime.

Most people would disagree with my parenting skills, but then I'm not a parent. I did not ask for this job; I certainly did not want it. On the contrary, I longed to have my old life back. I hated cooking; I wanted to go back to eating in restaurants or picking up the phone and calling for takeout delivery service.

There was only one consolation, one happy thought that would sustain me for the days and weeks ahead. School would start in September! Jeremiah would start kindergarten and be gone a good part of the day for ten months out of the year. But that blessed time was more than four months away. I had to get through the rest of the spring and the entire summer first.

As I rinsed out the breakfast dishes one morning in late April, I looked out my kitchen window to see that nearly all the snow had melted and the sun was shining. Maybe my nephew would want to go outside and play. Hoping to get him out of the house for a few hours, I decided to break my self-imposed silence and speak to him.

"It's going to be warm out today. Would you like to play in the backyard?"

Predictably, there was no answer.

"You really should get some exercise and fresh air."

He continued to behave as though he were deaf as well as mute.

"You can't stay in this house all day every day! I simply won't allow it."

The boy finally picked his head up and acknowledged my presence. Those blue eyes that I once thought so innocent in his beatific face now made me shiver at their icy coldness.

"Don't look at me like that!" I cried. "Like it or not, I'm your legal guardian. We might as well make the effort to get along. It was what your father would have wanted."

Jeremiah picked up the Magic 8 Ball that, like the Etch A Sketch, had become his constant companion. He turned it upside down and handed it to me.

I HATED MY FATHER.

I don't know which disturbed me more: the emotion those words conveyed or the fact that my nephew could somehow communicate his feelings through the toy.

"How did you do that?" I demanded to know. "When I was a girl, I played with this Magic 8 Ball hundreds of times and never got this answer before."

Jeremiah smiled as he reached for the toy, but the expression on his face was far from pleasant. Moments later, he handed it back to me.

I CONTROL IT WITH MY MIND.

My initial reaction to seeing that sentence was that a five-year-old was not capable of writing it. That meant my nephew was not only an artistic prodigy, but he was also a genius. What else was he, though? Did he have telekinetic powers like Stephen King's Carrie White? A well-educated woman, I had never been a believer in the supernatural. Could I have been wrong?

"How do you do that?"

NO MORE QUESTIONS was the answer he gave me before turning his attention back to the Etch A Sketch.

"No, you don't," I told him firmly. "You're going to explain this to me. I'm not ...."

My words failed me when I saw the screen of the Etch A Sketch. Jeremiah had drawn me again, but this time, he had included himself in the drawing.

"Why did you draw that?" I asked, tears filling my eyes as I spoke. "Is that what you want to do, stab me with a knife?"

I got my answer from the window of the Magic 8 Ball: IT IS DECIDEDLY SO (a standard saying included in the toy by the manufacturer).

"It's obvious you're not happy here," I said, trying to rein in the growing fear that threatened to consume me. "I will speak to my lawyer and see if other arrangements can be made."

Jeremiah seemed concerned about his future and initiated a conversation via the Magic 8 Ball.

WHAT ARRANGEMENTS? he asked.

"Maybe I can put you in a foster home or perhaps a boarding school."

NO SCHOOL.

"You're five years old," I explained. "You'll have to attend school in the fall anyway."

NO SCHOOL.

"Did you go to school in Switzerland?"

NO.

"Why not?"

I'M NOT SIX YET.

"So, you were going to start school next year if your father hadn't died?"

NO SCHOOL.

"Was Price planning to have you privately tutored at home?"

NO SCHOOL.

"This isn't getting us anywhere. You live in America now, and you have to attend school. It's the law."

NO SCHOOL.

"You can write full sentences and correctly spell the word arrangements. You must have had some form of education already."

I HATE SCHOOL.

"Why?"

There was defiance on Jeremiah's face as he took back the Magic 8 Ball. No matter how many times I repeated the question, he stubbornly refused to answer. Finally, he threw Ideal Toys' black plastic sphere at me, striking me in the face, a blow that I was sure would give me a black eye.

More than anything, I wanted to put the little brat over my knee and administer a good, old-fashioned spanking. But the saying in the toy's window stopped me in my tracks.

I'M GOING TO KILL YOU.

* * *

Afraid. Scared. Frightened. Terrified. Fearful.

Even though I locked my bedroom door that night, I could not fall asleep. Jeremiah told me that he had killed his father. Was he telling the truth? Reeling from the shock of my brother's passing at the time, I never asked Wolfgang Hagelin about the cause of his death. Could his five-year-old son really have murdered him? If so, then there was every likelihood that he would try to kill me, too.

I had to send him far away. But where? Was there anyone in Switzerland who would take him?

The first thing in the morning, I would call my late brother's attorney and tell him I could not honor Price's wishes. I'm sure there was no law—Swiss or American—that would force me to keep Jeremiah. There are plenty of people in the world who want to adopt children, I reasoned. Let one of them take him off my hands.

Having made up my mind to rid myself of my nephew, I closed my eyes and drifted off to sleep. It was after three in the morning when a noise woke me up. Someone was in my bedroom.

"Who's there?" I asked, which I suppose was a stupid question since there was only one other person in the house.

Trembling with fear, I reached my hand across the bed to the lamp on the night table and turned it on.

"Jeremiah! How did you get in here? The door was locked."

The Magic 8 Ball was tossed onto the bed.

NO LOCK CAN KEEP ME OUT.

Suddenly, in the light from the bedside lamp, I saw a flash of metal. I quickly shifted my weight, and the blade of the knife went into my Sealy Posturepedic mattress. Thrust into a fight or flight situation, I chose to fight. My weapon? The only one available to me: the Magic 8 Ball that was still in my hand. Although it was made of plastic, I brought it down with sufficient force to crush the five-year-old's skull. The toy shattered on impact, and the dyed-blue alcohol inside it mixed with Jeremiah's red blood and gray brain matter, giving my hands a ridiculous patriotic appearance.

* * *

What good are words? No one believes what I say—least of all the police. I was arrested and charged with first-degree, premeditated homicide. Since my victim was of tender age, the district attorney was hoping for the maximum penalty. To the public and press, I was a monster.

"Yes, I hit Jeremiah over the head with the toy," I told Carmine Amato, my defense attorney. "But I acted in self-defense. He came after me with a knife."

"There's no proof of that. The prosecutor will no doubt argue that you placed the weapon in your nephew's hand after you killed him."

"I thought in this country everyone was assumed innocent until proven guilty."

"You bashed in the brains of a five-year-old. No jury is going to believe he came after you, a grown woman."

"But he did. He killed his father, too."

"I checked with the Swiss authorities. They say your brother committed suicide as did his wife. He shot himself."

"Jeremiah shot him. He told me so. For all I know, he also killed his mother."

"Again, we have only your word that the boy was dangerous. And when the prosecutor shows the crime scene photographs during your trial, which he will, people will want to crucify you. There will be mothers and fathers on that jury. They won't understand how you could brutally murder a child."

I could tell from his demeanor that Carmine, who had two children of his own, would not mind it too much if he lost this case. He obviously believed I was guilty. After a sensational trial that made headlines on both sides of the Atlantic, the twelve men and women of the jury agreed with him. Since the Commonwealth of Massachusetts had recently abolished capital punishment, I was sentenced to life imprisonment without the possibility of parole.

Three days before my first Christmas as a guest of the Massachusetts Correctional Institution in Framingham I received a package during mail delivery.

"What's this?" I asked Coral Liddy, the guard on duty.

"How should I know," she replied brusquely. "I'm no mind reader."

The cellophane tape used to seal the plain brown paper packaging was loose, a sure sign that someone at the prison had opened it before it was delivered to me. I was not surprised. The officials could not risk contraband being sent through the mail.

There was no return address, so I had no idea who sent it. Curious, I tore the paper off the box.

"Is this someone's idea of a joke?" I cried when I uncovered the Magic 8 Ball. "I don't want it. You take it."

"What am I supposed to do with it?"

"You can throw it in the trash for all I care."

I passed the Magic 8 Ball through the bars to the tall, stocky prison guard.

"Will this child killer ever be a free woman again?" Coral laughingly inquired and turned the toy upside down to read the answer. "OUTLOOK NOT SO GOOD. What do you know? This thing really can predict the future."

Salem created a self-portrait on his Etch A Sketch (but he used a magic pencil spell to draw it).