Maison Noire

Mandy and Clint Holroyd pulled their Subaru Forester into the cobbled driveway of the new two-story colonial house on Revere Road in quaint Maple Ridge, Massachusetts. After turning off the vehicle's engine, Clint put his arm around his wife, and the two looked at their new home with a deep sense of pride. They had worked hard and saved for many years to afford such a place.

"I can't believe it's ours," Mandy said.

"Technically, it belongs to the First New England Mortgage Company," Clint laughed.

"Too bad they're not here now to give us a hand with all the unpacking," Mandy joked while reaching into her handbag for the key to the front door. "Come on, handsome. It's time to carry me over the threshold."

"Again? I seem to remember doing that twelve years ago when we got back from our honeymoon in Bermuda."

"That was the threshold to our rented apartment; this is our first real home."

After Mandy unlocked the door, Clint picked her up, tossed her unceremoniously over his shoulder and carried her into the house fireman style. The sight of the dozens of cardboard cartons waiting to be unpacked dampened their good humor.

"I have a feeling we're going to be living out of boxes for the next month," Clint groaned.

"The sooner we get started, the sooner we'll be done. I suppose we should begin with the things we use most. Why don't you go upstairs to the master bedroom and start unpacking our clothes and toiletries while I tackle the kitchen."

They worked from midmorning to late in the evening, finally stopping when Clint's growling stomach could be heard above the sound of the radio. After a delightful dinner at the Maple Tree Inn, they returned to their new home and fell asleep on the couch while watching television.

The following morning the Holroyds, who were both suffering from aching muscles, had a quick breakfast of coffee and instant oatmeal and immediately resumed unpacking.

"I'm going to go set up the computer and unpack all the office supplies," Mandy said. "Call me when you want to take a break for lunch."

The architect who designed the house had included a single-story addition on the side of the building consisting of a garage and a spare room that was perfect for a home office. It was one of the features that attracted Mandy to that particular design because she did much of her work online. There were no windows in the office, but enough light filtered in from the adjoining kitchen to allow her to see inside the dim room.

"I could use some more light," she said, looking for the box that contained the office lighting fixtures.

Twenty minutes later she walked upstairs, carrying a desk lamp in her hand.

"Clint," she called up the stairs, "when you're done in the guest room, could you take a look at the electrical outlets in the office. They don't seem to be working."

"What do you mean?"

"When I plugged this lamp in, it didn't work; so, I replaced the bulb but still no light. Next, I tried it in the laundry room and it worked fine. I then went back into the office and tried the lamp in all three outlets. It didn't work in any of them."

Clint checked the circuit breaker box, but not a single switch was in the "off" position.

"None of the circuits have been tripped," he announced. "There's probably a broken wire somewhere. Can you set up the computer in another room until I get a chance to check it out?"

"Sure. I'll be working on getting this place organized for a few days. I won't have time to go on the computer."

The following morning Clint went into the office to check the electrical outlets, bringing his Mag-Lite flashlight with him so that he could see. When he pressed the switch, however, nothing happened.

"Mandy, did you unpack the batteries yet?"

"Yeah, I put them in the drawer next to the refrigerator. Why?"

"My flashlight is dead."

"It can't be. I just put batteries in it last week when I was cleaning out the closets in the apartment."

Mandy picked up the flashlight and pressed the switch. The beam came on immediately.

"There's nothing wrong with this light," she said.

"It wasn't working a minute ago. Maybe the contacts are loose."

Clint went back to the office, but again the flashlight would not work. After uttering a few choice words, he went out to his car and got the Coleman flashlight out of his glove compartment. As he walked back into the house, he pressed the on/off switch several times. The Coleman was working perfectly—until he got to the office, that is.

"What the hell?" he asked, perplexed.

He went back to the living room and complained to his wife.

"It's the weirdest thing. Neither of my flashlights will work in the office. Do we have any candles?"

Mandy opened the dining room china cabinet and took out a decorative taper.

"Will this do?"

"I'll try it."

As soon as Clint crossed the threshold into the office, the flame went out.

"Something's definitely wrong in that room," he later told his wife as the two had a midmorning cup of coffee. "I couldn't keep the candle lit, and neither the fireplace lighter nor the matches from the kitchen would light inside the room. If I go out into the garage and light the candle, as soon as I go back into the office, it blows out again."

"Is there a draft?" Mandy asked.

"No. And besides, a draft wouldn't affect the flashlights or the desk lamp."

"Don't worry about it, honey. I'll call the builder in the morning and have him send over an electrician to sort things out."

"Electrician, hell!" Clint laughed. "I think we need an exorcist."

* * *

The electrical contractor arrived at three. Clint showed him into the office, not bothering to go into details about the problems he had experienced the day before. He merely told the electrician that there was no juice in the outlets.

Just as Clint had experienced the previous day, the minute the electrician entered the den his flashlight went out.

"I'll be damned," he swore. "Something's wrong with my flashlight."

"It's not your light," Clint informed him. "It's this room."

The electrician put a light at the end of an extension cord that when plugged into the garage would reach all the way into the office. Yet, when he crossed the threshold into the windowless room, the light—like the flashlight, candle, lighter and matches—would not work. Oddly enough, when he plugged Mandy's electric pencil sharpener into the outlet, it worked fine.

"I can't explain it," the electrician said as he stepped over the threshold and back several times, watching the lamp go on and off as he did. "Everything checks out. You've got plenty of juice going into those outlets. I've never seen anything like this before. Whatever the problem is in that room, it has nothing to do with the electrical wiring."

"Maybe we should call that exorcist," Mandy said jokingly.

Instead of appealing to the local Catholic church for help, Clint phoned a fellow worker whose husband once taught a course in parapsychology before leaving his position to become a writer. Soon thereafter, a team of volunteers from the Drexler Paranormal Research Center set up their base camp in the Holroyds' basement during which time they monitored electromagnetic, geomagnetic, electrical and electrostatic fields in and around the home office. They also used infrared photography, motion detectors, specialized night vision equipment, computer image analysis and audio recorders on multiple frequencies.

"Well, have they found Casper yet?" Clint asked Mandy when he came home from work one night, a month after they had moved into their new house.

"I haven't the slightest idea. I asked Professor Stern what was happening, and he started going on about rapid thermal changes, cold spots, ionizing radiation and gamma rays."

"Sounds like an episode of Star Trek."

"The bottom line is we still can't turn on a light in that room."

Unable to solve the Holroyds' problem, the team of parapsychologists apologized and then packed up and went back to Drexler.

"Now who should we call?" Mandy asked with growing irritation.

"The Ghostbusters?" Clint replied, equally frustrated.

For want of a better idea, Mandy found a psychic listed in the phonebook and gave her a call.

Jeannelle Maureau had recently moved to the United States from France and had some difficulty with the English language. She walked into the office, closed her eyes and tried to sense if there was any spiritual activity going on.

"Maison noire," she mumbled over and over again.

"What's she saying?" Clint whispered in his wife's ear.

Mandy shrugged her shoulders.

"Don't ask me. I took Spanish in school, not French."

After half an hour, Jeannelle and the homeowners left the office and gathered in the living room.

"There is definitely something in that room," the psychic announced in heavily accented English.

"Some-thing?" Mandy echoed.

"A restless spirit that has not yet gone over to the other side."

The Holroyds looked at each other, uncertain whether to believe the psychic or not. Clint then turned to Jeannelle.

"When you were in the office, you mentioned some guy named Mason. Is that the person who's haunting our house?"

"Mason? I don't know what—oh! maison. That is the French word for house."

"You said something like maison nor."

"Maison noire?" the psychic asked.

"Yes. That's it. You kept repeating that phrase over and over. What does it mean?"

"Black house."

Although Jeannelle insisted the house was haunted, she could not identify the person whose spirit had staked a claim on the Holroyds' office.

"I have tried to make contact with it, but I get no response, just a feeling of unrest, sadness and fear," she explained.

"And that was just from us," Clint commented facetiously.

"You may think this is funny, Mr. Holroyd," Jeannelle said, "but there is a tormented soul in your house. It needs assistance in order to pass on to the other side."

"What can we do to help it?" Mandy asked.

"You must find out who it is and what holds it here."

"How do we do that?"

"You can begin by looking into the history of this house."

"It has no history," Clint said. "It was just built. We're the first people to live here."

"If the ghost has no connection to the house itself, then look into the history of the land. Perhaps there was another house here at one time."

Questioning the neighbors did little good. All the houses in the area were new, and the owners—like the Holroyds themselves—had moved there from out of the area. First, Mandy tried her luck at the town library where she searched through back issues of The Maple Ridge Tribune but could find no stories of murder, disappearance or mysterious death in the vicinity of Revere Road.

Her next stop was at the local historical association where a sweet old man invited her inside and offered her a cup of coffee.

"Are you a teacher?" the elderly volunteer asked. "Seems that most of the visitors we get are teachers who want information on local history to present to their students."

"No. I just moved into the area from Boston, and I'm curious about what buildings might have stood on my property before my house was built."

"Where do you live?"

"The eastern end of Revere Road, not far from the old bridge."

"Ah yes, so you moved into that new two-story colonial? Your lot and all the surrounding property were once part of a large farm."

"A farm?"

"Yes. One that used to belong to old Ichabod Van Buren. It was in his family for generations, all the way back to the early 1800s. After old Ichabod passed on, his son sold the farm to a developer and retired to Florida. People today just don't want all the hard work involved with farming."

"What about the farmhouse? Where was it located?"

"It's still there. Coretta Hoover bought it. She lives upstairs and turned the lower level into a beauty parlor."

"Were there any other buildings or houses on the property? Maybe a small one belonging to a relative or a farmhand?"

"No. There was the barn, of course, right next to the house, but Coretta tore it down and had a garage put up instead."

Mandy momentarily hesitated before asking her next question.

"Have you ever read about or heard of any violent deaths or accidents that might have occurred on that property?"

The old man looked at her strangely and then replied, "No, can't say that I have. Ichabod died in the hospital. His wife spent her final days at a nursing home in Taunton."

Mandy was uneasy, not sure how the old man would react to further questioning.

"I know this sounds ridiculous," she began. "But my husband I have been experiencing trouble in our house. We can't get any lights to work in one of the rooms."

"Perhaps I could recommend a good electrician."

"Thank you, but we've already called one. He was at a complete loss to explain the problem. We had a psychic come to our house, and she said there was a restless spirit there and that it wouldn't go away until we helped it find peace."

Mandy was sure that the historian must think her either a fool or a madwoman, but the old man, who had seen a lot in his years, gave her the benefit of the doubt.

"I'm sorry I can't be of any help to you. I know of nothing that happened on that property that could explain the presence of a ghost. But," he said, walking over to his desk, "perhaps Ichabod's son could tell you things about the family homestead that I'm not aware of."

The old man opened his rolodex, wrote down a name, address and telephone number on a piece of paper and gave it to Mandy.

* * *

Wednesday afternoon the FedEx deliveryman rang the doorbell of the two-story colonial house on Revere Road. Mandy signed for the large, heavy package and then opened it on the dining room table. Inside were a genealogy of the Van Buren family, several photograph albums, the family Bible and half a dozen old journals that Van Buren had found in his father's attic before Coretta Hoover bought the place. Mr. Van Buren had graciously consented to allow the Holroyds to borrow the items, provided they returned them to him when their investigation was concluded and did not sell them on eBay.

Mandy took the photo albums into the living room and curled up in her wing chair to look through pictures of generations of Van Burens. There were photographs of sleeping babies, smiling children, blushing brides, somber-looking old women, tired-looking old men and young men in various military uniforms dating all the way back to the Civil War. Eventually, she came across a snapshot of a Van Buren family reunion. In the foreground of the photo was a small cluster of blackberry bushes, ones that could still be found in her neighbor's yard. Beyond the bushes was a wide field that would later be subdivided—part of which became her property.

When Clint came home that night, Mandy showed him the photograph.

"That's our yard, all right," he said. "Our house stands right about here, where this old oak tree is standing in the photograph."

"That's a huge tree," Mandy commented. "What a shame they had to chop it down."

"Yeah," Clint agreed. "I'll bet the builder got quite a few chords of firewood out of that one."

"A tree that size must have been at least two or three hundred years old, which means there was never a building on that spot."

The following day Mandy returned to the Van Buren family heirlooms. She briefly studied the genealogy and then thumbed through the family Bible, but there was nothing of importance to her search in either one. Finally, she picked up the half a dozen diaries and returned to her wing chair. She read all afternoon but could find nothing to shed light on the identity of the restless spirit.

She put the books aside long enough to cook, eat dinner and clean up the kitchen. Then she returned to the journals. She had already read three from cover to cover and now picked up a fourth. It looked older than the others; its pages were yellowed with age and brittle to the touch. She would have to be very careful while reading it.

According to the inside cover, the journal belonged to Mrs. Adelaide Van Buren and had been started in 1833. The first half of the book centered on the usual hopes and fears of a young woman. Adelaide expressed her concerns about marrying Webster Van Buren. She was only a young girl of seventeen and did not know what to expect out of marriage, but apparently, her concerns were unfounded. The teenager quickly adapted to her new domestic situation. After sixteen months of marriage, she gave birth to a baby boy, a year later she had another and a year after that, she had a girl—her last child.

The Van Burens were a happy family. The children were all healthy, the farm was doing well and Adelaide and Webster were very much in love. Then one day, when Adelaide called her children to supper, Becky, her daughter, did not come in from outside. The worried parents searched the entire farm but to no avail. Three days later the little girl's body was found in a nearby wooded area. The child had apparently been molested and strangled.

Mandy's heart beat rapidly. Was the spirit in her home office the ghost of Becky Van Buren?

There were several blank pages in the journal, and then the writing continued. Mandy looked at the date at the top of the page. There was a gap of more than twenty years between Adelaide's writing of her daughter's death and the continuation of her diary. Mandy sympathized with the poor mother. She must have been too heartbroken to write.

The later entries were quite different from those at the beginning of the book. It was as though a different woman had penned them. Gone was the romantic young girl who looked with hopeful eyes to the future. What remained of Adelaide Van Buren was a lonely old woman, tortured by memories of her past. Webster died ten years after his daughter was found murdered. He apparently had taken to drink after the tragedy, a habit that later killed him. The two boys were grown and both in the army, proudly serving under Ulysses S. Grant. Adelaide was left alone in the house with nothing but photographs and memories to keep her company.

Maybe it's not Becky's ghost in our office, Mandy thought after further consideration. It might be the spirit of her mother, Adelaide Van Buren. Perhaps she's waiting for her two sons to return from the war. But even if Adelaide is the restless spirit, why would she choose to haunt our house? Why not haunt Coretta Hoover's beauty shop? After all, that was where she and her family had lived.

Still puzzled over the identity of her unseen houseguest—if one actually existed—Mandy returned to Adelaide's journal. After writing several pages of prayers for the souls of her daughter and husband and for the safety of her sons, Adelaide confessed a dark secret to her journal, one she could not bring herself to tell to another living soul and yet one she could no longer bear alone.

Not long after Becky's murder, the local police found a homeless drifter sleeping in the woods not far from the spot where the poor girl's body had been found. He was immediately bound and taken to the Van Buren farm since the police were certain that Webster Van Buren would want to confront the man who molested and murdered his daughter. Webster, a fair and compassionate man, questioned the drifter about his possible involvement in Becky's death. When the man failed to deny the charges, Webster, four policemen and five of the Van Burens' farmhands took the drifter out into the yard and hanged him from a large oak tree.

Oh, my God! thought Mandy, who had been sitting on the edge of her seat as though watching a thriller on television.

With some difficulty, Adelaide continued her story. Just two days after the hanging, a young man was picked up in a neighboring county for molesting and strangling a little girl there. After his arrest, the man confessed to murdering not only that child but also Becky Van Buren. Both Adelaide and Webster were horrified by the knowledge that an innocent man had paid the ultimate price for a crime he did not commit, but there was nothing they could do to right the grievous wrong since the man was already dead. Webster never got over his part in the lynching. It was his guilt, not bereavement over his daughter's death, that drove him to drink.

All the men involved in the hanging of the drifter agreed never to speak of the tragic matter again. They buried the body in a secret grave, and since no one knew who their victim was or where he had come from, there was little chance anyone would notice he was missing. All those who knew of the foul deed were sworn to secrecy, Adelaide included. But her frail old bones could not bear the weight of that secret any longer.

"After they cut the poor man's body down," Adelaide concluded, "he was thrown into a hastily dug grave a few yards from the oak tree."

Mandy clutched the diary in her hand and ran upstairs to tell Clint of her discovery.

* * *

The following afternoon Mandy went to see the owner and editor of The Maple Ridge Tribune. Expecting her words to be met with incredulity, she told him about the electrical problems in her home office and the medium's insistence they were caused by a restless spirit.

"This is an account of a lynching written by a woman who once lived nearby," she announced and handed over Adelaide Van Buren's diary.

After perusing the journal, the newspaperman turned to his visitor. To her surprise, he seemed to give the story credence.

"I assume you came to see me for more information about these events. I'll see what I can do, Mrs. Holroyd. First, we have to verify that the diary is based on fact and was not intended to be a work of fiction or was the product of a disturbed mind."

"How do we do that?" Mandy asked.

He turned in his swivel chair and booted up his desktop computer, one he rarely used because he preferred the portability of his laptop.

"Do you have all the back issues of the Tribune online?" Mandy asked hopefully.

"Yes. Thanks to some dedicated interns from the community college, our computerized archive goes back to our first issue in 1765. My ancestor, who started the paper, was one of the Sons of Liberty."

He began his search by typing in the name VAN BUREN.

"Ah, here we are. In June 1843 the body of Rebecca Van Buren was discovered in a wooded area along Revere Road."

"That's got to be Adelaide's daughter. So that much of her story is true."

"Yes," the editor agreed. "The timeframe is correct, but it says here that she died from the result of injuries due to a fall."

"Is it possible that either the family or the police wanted to keep the girl's rape and murder from the public?"

"It's not only possible, it's very likely the case here. The Tribune wasn't a newspaper that favored yellow journalism. Still, we now know Becky existed and died as a child. We should continue under the assumption that the events described in the journal took place."

The editor quickly scanned the paper's archives for other references to the Van Burens, but he could find nothing that would shed light on the identity of the unfortunate man who had been hanged from the oak tree.

"Don't give up hope just yet," he said, noticing the look of disappointment on the woman's face. "Maybe this drifter's disappearance didn't go entirely unnoticed."

"Is there anything about a missing person around that time in the Tribune?

"No, but I have access to a database containing old police reports from towns all over the county. I'll see what I can find there."

Mandy's emotions rose and fell like a roller coaster car as the editor found several missing persons cases, only to rule them out when he read the details in the reports.

"Here's another one," he said. "Wait, no. It's a woman."

"I never realized how many people went missing back then."

"What's even more amazing is how many go missing now," the editor replied. "Given the number of cell phones, closed circuit television cameras and other security devices, it's hard to believe people still vanish without ...."

He stopped speaking and concentrated on the police report he was reading.

"What is it?" Mandy asked when she saw the look of excitement on his face.

"It seems a Mortimer Polk was reported missing a week after the hanging on the Van Buren farm. Polk lived in Gloucester and, according to his sister, he'd been making the rounds at farms up and down the north shore looking for work. Then one day he didn't come home. The sister was most upset because her brother was a deaf mute."

"A deaf mute?" Mandy echoed. "That would explain why he didn't deny the accusations against him. He wouldn't have been able to hear them, and even if he could, he wouldn't be able to voice his innocence."

"There's vigilante justice for you! The fools hanged an innocent man."

"Yes, and apparently their unfortunate victim is buried beneath my home office."

"What do you intend to do about it?"

"What can I do? I can't very well tear down my house, and yet Mortimer Polk's spirit will probably never rest until I do."

"Not necessarily. We've discovered what happened to him and thereby metaphorically unearthed his body. If I use this information to write an article for the paper, we can finally let the truth come out. Do you have any objections?"

"No. I'm only sorry Polk's sister never learned what happened to her brother."

The sun had already set when Mandy drove home that night after helping the editor write an account of what took place on the Van Buren farm back in 1843. When she pulled into the driveway of her two-story colonial, she was amazed to see the lamp in the office shining brightly through the row of windows in the garage door.

Tears misted in her eyes yet she smiled, knowing that Mortimer Polk's spirit had found peace at last.

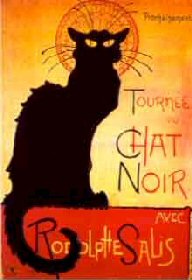

Oh no! It's Salem, a.k.a., the dreaded le chat noir!