Summer Youth Camp

Sally Ferguson helped her thirteen-year-old son, Marshall, pack his bags. She smiled bravely and assured herself that everything would be all right.

"Did you remember the sunscreen?" she asked for the third time. "You know how quickly you burn. And don't forget the calamine lotion, the insect spray and the antibiotic cream."

"Mom, I'm only going to camp for a week; I'm not enlisting in the Army."

"But you've never been away from home before, honey" she pointed out stubbornly.

"Dad said it will be a good experience for me."

Sally started to fume at the mention of her ex-husband. Of course, he would want the boy to go to camp. They had always disagreed on what was best for their son. Mac Ferguson believed in treating him like a normal boy. He thought Marshall should join the Little League or the youth soccer association. He had even encouraged Marshall to play football and basketball with the other boys in the neighborhood.

"A kid his age ought to be outside running around. It's not normal to keep him cooped up inside all day," Mac had argued time and again. "Despite his high intellect, he is just a child."

"He's a genius, and that wonderful brain of his needs to be nurtured. As his parents, it's our duty to see that he is properly educated."

"That's why I agreed to let you enroll him in that private academy, but I won't let you chain him to a computer twenty-four hours a day. He needs exercise, fresh air and a little fun. Most of all, he needs to be with kids his own age."

"He socializes with the boys at school."

"You call that socializing? They go to museums and technology workshops. When I was thirteen, I was already going to school dances."

"Now that's a great idea!" she cried sarcastically. "Do you know what goes on at those dances?"

"You can't fight nature. Soon Marshall will be more interested in females than in emails."

"We'll see about that!"

Sally was adamant. Her son was not going to grow up and be like the other boys in the neighborhood who would be lucky to get a mediocre education at a state college. Frankly, they were more likely to wind up taking auto mechanics at the county vo-tech.

Marshall, on the other hand, would attend MIT and be sought after by high-tech corporations such as Microsoft, Apple or perhaps even NASA. His mother gave little thought as to how she would afford MIT's sizeable tuition on a secretary's salary. Such details had no effect on her carefully formulated plan for her son's future.

"You can't run Marshall's whole life," Mac said with exasperation.

Up until now, Sally had been doing a damned good job of it. Then Essex Academy announced this absurd field trip. Her son and his classmates, all with genius-level IQs, would spend one week camping out in the wilderness, sleeping in tents, cooking over an open fire, swimming and boating in the lake and hiking in the woods. God only knew what kinds of harmful insects—or even snakes—were waiting to prey on her precious little boy.

But even though the overprotective mother was against the trip, the school stressed its importance, so she reluctantly consented.

* * *

Marshall and his mother waited in the school parking lot for the bus to arrive. Sally looked at the other parents waiting in their cars with their sons. Were they all as worried as she was, or were some secretly pleased to have a week to themselves?

The headmaster of the Essex Academy for Gifted Children arrived and immediately started barking orders.

"All right, boys. Line your luggage up on the curb here. The sooner we get the bus loaded, the sooner we'll be on our way."

Sally opened the trunk and took out one of Marshall's duffel bags. Her son picked up the other. Underneath the bag was the black case in which he carried his Dell laptop.

"You're not bringing your computer with you. It cost your father and me a small fortune. What if it gets stolen?"

"None of the boys would steal it. They've all got computers of their own. Besides, the professor asked us to bring them. He's got some special project planned for us."

"I guess it's okay, then," she said begrudgingly, hoping that should anything happen to the computer, the school would replace it.

Moments later a large touring bus pulled into the parking lot. As if on cue, mothers and fathers hugged their sons and gave them last-minute warnings and advice. The boys, many bravely holding back tears, dutifully promised to write and be on their best behavior. Sally hugged Marshall just a little tighter and a little longer than the other mothers did. He was, after all, her only child and the center of her universe. This had been the case even before her marriage ended, but it had never occurred to her that her single-minded devotion to her child might have been the cause of its failure.

"I'm going to miss you so much," she cried, clutching Marshall to her bosom.

"I know, Mom," he said uncomfortably, trying to extricate himself from her grasp.

He was thirteen, too old to be coddled like a baby. His mother finally loosened her hold on him, and the boy headed toward the bus. Then he spotted his father's Dodge Intrepid pulling into the parking lot.

"It's Dad!" he exclaimed jubilantly. "Daddy!" he called and sprinted across the parking lot.

"Sorry, I'm late. I got caught up in traffic. I was afraid I was going to miss seeing you off," Mac said, throwing a loving arm around his son's shoulder.

Sally jealously watched as her son and ex-husband played out their ridiculous display of male bonding. She hated the way the boy's eyes lit up every time he looked at Mac, for no matter how hard she tried, she could never parallel the close relationship Marshall shared with his father.

"Okay, boys," the headmaster called. "Say goodbye to your parents and get on the bus."

"Don't forget to send me a postcard, okay, buddy?"

"I won't, Dad. But if they don't have postcards, will you settle for a letter?"

"Only if you write it yourself. I don't want anything you've dashed off on your word processor."

"It's a deal," Marshall said, giving his father one last hug. "Bye, Mom," he yelled and boarded the bus.

Sally continued to wave until the chartered vehicle disappeared from view.

"What time is he supposed to get back next Sunday?" Mac asked.

"Why?" his ex-wife replied angrily.

"So that I can be here to welcome him home."

"Do you have to come?"

"Why shouldn't I? Whether you like it or not, I am the boy's father."

"How can I forget it?" she said under her breath, but Mac heard her just the same.

"If you don't tell me what time he's due back, I'll just call the school on Monday."

"Why must you spoil everything? I planned something special for Marshall and me next week."

"Don't worry; I won't interfere with your plans. I promise I won't spend more than twenty or thirty minutes with him, just long enough to hear the highlights of his trip. Then you can have him all to yourself—as usual."

* * *

Sally struggled to get through the week. Every day she checked the mail, but there was no letter or postcard from Marshall. Finally, Sunday arrived. She dressed in her best outfit and took great care putting on her makeup. It was almost as if she were preparing to meet a date rather than a son.

She arrived at the school parking lot an hour before the bus was due back, just in case it returned early. She brought a paperback book to read while she waited, but her mind kept drifting from the story to her son. The minutes ticked by slowly. Eventually, other cars pulled into the parking lot; other parents were waiting for their sons. Ten minutes before the bus was due back, her ex-husband's Intrepid parked next to her Honda.

"Mac," she called, jumping out of the car, "have you heard from Marshall?"

"No, why? Has something happened?"

"I don't know. I never got a letter from him."

"That's nothing to worry about," he laughed. "When I used to go to summer camp, we always waited until the last night to write to our parents. We got back home before our letters arrived."

Sally eyed him suspiciously. At one time he might have said these things just to keep her from worrying, but those days were long gone. Too many ugly scenes and bitter arguments had left them insensitive to each other's pain.

Mac looked at his watch and announced, "He should be here any minute. Unless they got a late start or ran into traffic upstate."

His ex-wife took a deep breath. Her nerves were already honed to a fine edge. In imagining Marshall's homecoming, she had not given any thought to his being late. Ten minutes went by, and there was no sign of the bus. Sally, the only one who seemed worried by the lateness of the hour, began to pace between her car and the end of the parking lot. Forty minutes later, other parents began to show signs of restlessness and concern. When the bus was two hours past due, anxious mothers and fathers began to gather in the middle of the parking lot, asking each other questions.

"Does anyone have the number of the camp?" one mother asked.

"No," another replied. "The headmaster told me that in case of an emergency, I was to call the school and leave word with the staff."

"This is Sunday. There's no one around."

One father pulled a cell phone out of his pocket and asked his wife, "What's the name of the camp?"

"Camp Hope, I believe."

Several mothers nodded their heads in agreement.

The father walked away from the crowd of parents to better hear the person he was calling. A few moments later, his raised voice drifted back to the others.

"What do you mean there's no such place as Camp Hope? Well, look again. Check the yellow pages. How many camps can you have in that area anyway?"

The parents held their breath and stared at the father with the cell phone.

"I see. Yes, thank you."

He took the phone from his ear and dialed again. This time, he phoned the police.

* * *

Detective Melvin Kramer tried to quiet the hysterical parents who were crowded into one of the department's interrogation rooms.

"Ladies and gentlemen, please! If we're to find your children, we're going to need your help."

The detective's use of the word if was not lost on Sally. Apparently, it was not lost on Mac either because he grabbed her hand and held it tightly.

"Now," the detective began, opening a manila file folder, "it's true that there is no Camp Hope. But we're putting an APB out on the bus. Did any of you get the license plate number or the name of the bus company?"

The parents shook their heads and then looked helplessly at each other.

"What about a description of the bus driver?"

Again, they could be of no help.

A young police officer walked into the room and whispered to Detective Kramer. After he left, the grave-faced detective addressed the parents.

"I have some bad news for you folks. We've checked with the State Department of Education. They say they have no record of an Essex Academy for Gifted Children."

* * *

Detective Kramer scanned through the pages of information he collected on the parents of the missing boys.

"I just don't get it, Gus," he confessed to his partner. "Not one of these parents has enough money to justify a kidnapping of this magnitude."

"But forty-two boys were on that bus," Gus Burgess replied. "Maybe all their parents are expected to chip in to get them back."

"No. My gut tells me this isn't about money."

"If it were only one kid, you could say it was a family member hoping to get illegal custody. But an entire bus full of kids? What other motive could there be except financial gain?"

"These guys, whoever they are, ran a pretty elaborate scam. I was in that phony school they set up. Quite a bit of money was invested there. They would have to have expected a handsome return just to cover their expenses. Most of these kids' parents could barely afford the tuition they were paying, much less meet any ransom demand."

"Maybe there was one particular boy the kidnappers wanted, and they took the whole bunch just to throw us off track."

"Why go through all that expense and trouble for one boy? It's a lot easier to kidnap one kid than forty-two. No. I think whoever took these kids sought them out specifically because they're smarter than other children. Hell! They're smarter than most adults."

"Who would want to kidnap a busload of computer geeks? Hey, I know! Maybe Microsoft is looking for child labor."

His partner's mockery only made Detective Kramer concentrate more on this particular line of investigation.

* * *

Lately, Mac Ferguson found himself spending more time at his former home than at his current one. His ex-wife was so distraught at the disappearance of their son that her doctor had to prescribe a tranquilizer. When Mac was not at work, he would stay with Sally, partly to watch over her and partly to wait for word of Marshall. When he arrived at the house one night, he found Sally asleep on the couch. Without waking her, he went to the kitchen and heated up a frozen dinner in the microwave. No sooner did he sit down to eat, than the doorbell rang. He left his Swanson Salisbury steak on the counter and went to answer the door.

"Mr. Ferguson, can I have a word with you?"

Mac's heart lurched when he saw Kramer on the step.

"Is it Marshall?" he asked with a tremor in his voice. "Is he ...?"

"Oh, no. We haven't found the boys yet," Kramer said.

"Then there's still hope," Mac said, relieved that the detective was not the bearer of bad tidings. "Come in, please."

"Mr. Ferguson, I've been talking to some of the other parents about the school and this supposed camping trip. To be honest with you, they didn't seem to know that much about the school. I'm hoping you can tell me something that might shed light on the kidnappers' motives."

Mac shook his head.

"You know, neither my wife nor I went to college. I barely made it through high school. In fact, when I first learned my son was some kind of genius, I began to suspect my wife of being unfaithful."

A humorless laugh escaped his lips.

"Did someone at the public school refer you to this academy for gifted children?"

"No. A representative from Essex contacted my wife."

"And she just sent your son there, without checking the school's accreditation?"

"Listen, Detective. This guy showed up, waved his degrees in front of my wife, showed her an impressive-looking brochure and told her that our son might be the next Albert Einstein. Then we went on a tour of the school and saw a model academic facility with a state-of-the-art computer lab. How were we to know it wasn't on the level?"

Kramer realized he had put the father on the defensive, something he had not intended to do.

"I know what you mean, Mr. Ferguson. I saw those classrooms myself. They were better equipped than most college campuses I've visited."

"Marshall had a keen interest in computers. We thought that he could learn so much more there than in public school."

"I don't suppose your son discussed any details of this trip with you?"

"Only that he was looking forward to swimming and hiking and the usual ...."

"I didn't want him to go," Sally cried as she came into the kitchen. "I never should have left him get on that bus."

"Please," Mac said, trying to calm her. "Don't blame yourself. You didn't know."

"He was too young, and he'd never been away from home before. It's all your fault!" she screamed at her ex-husband. "You were the one who wanted him to go, to be like other children. Are you satisfied now?"

"Sally, he's thirteen years old. It's time to cut the cord!"

"How dare you?"

"All right, stop it!"

Kramer's shout silenced the squabbling parents.

"This isn't going to help us find your son. Now think! There must be something you can tell me about this trip. Maybe one of the boys planned on bringing cigarettes, beer or a couple of old issues of Playboy magazine. Anything at all."

"My son was a good boy!" Sally declared, offended by the detective's suggestion. "When he wasn't doing his schoolwork he would spend his time on the ...."

A memory suddenly came back to her.

"What is it, Mrs. Ferguson?"

"The Dell. He took his laptop with him. I told him not to, that it might get broken or stolen, but he said all the boys were bringing theirs."

"What good is a computer on a camping trip?"

"Marshall said the headmaster told him that he had some special project planned for the boys."

Kramer's hunch had been right. The kidnappers were not interested in money. His task now was to learn more about the headmaster's special project.

* * *

"Found anything yet?" Kramer asked Gus when he walked into the station the following morning.

"Not a damn thing. The only fingerprints we've been able to identify were those belonging to the kids. Seems the school district fingerprinted them in kindergarten. The other prints, which I assume belong to the teachers, are not on file."

"Great! No fingerprints, no criminal records."

"And there are no papers in the school that identify any members of the faculty or the administration. No payroll records, no union or insurance information, no personnel files—nothing. Officer O'Brien's wife is a high school teacher. When the forensics team was done scouring the area, she took a look at the books and papers that were left behind."

"And?"

"She said there was nothing out of the ordinary, just the typical textbooks, old homework assignments and tests to be graded. The only difference here was that the subject matter was highly advanced for kids their age, which was to be expected since it was a school for gifted kids. What about the parents? Were they of any help?"

"No. Can you believe it? Not one of them can give me a single surname connected with the staff at the school. They say their kids referred to the faculty members only as the headmaster or the physics teacher or Professor Otto. It seems the school liked the teachers and students to communicate on a first-name basis."

"So, the parents don't even know the teachers' names."

"They've all agreed to search through their sons' rooms, closets, desks, and backpacks and hand over all the papers and books they find to us. When they do, we can ask O'Brien's wife to have a look at them, too."

By late afternoon, various boxes and shopping bags of notebooks, textbooks and school papers were stacked up on the long table in the interrogation room. Detectives Kramer and Burgess waded through loose-leaf binders, trying to decipher the boys' handwriting. Kathleen O'Brien sat behind a computer, checking the contents of various CDs and flash drives the parents had found among their sons' effects.

"Find anything interesting?" Kramer asked his partner who was intently studying the contents of a well-worn Red Sox trapper keeper.

"Listen to this," Gus said and then proceeded to read aloud from the missing student's notes. "The force of attraction between two separate masses depends, first, upon the amount of mass in each one, and second, upon the distance between the masses. The masses must be multiplied together, and the pull diminishes with the square of the distance. If the distance is doubled, the pull is only one-fourth as great." He then put the trapper keeper down and asked Kramer, "What the hell were they teaching these kids?"

"That's Newton's law of gravity," O'Brien's wife explained. "Guess you didn't study physics in school."

"Physics?" Gus laughed. "Are you kidding? I flunked algebra."

Mrs. O'Brien took the trapper keeper from him and carefully examined its contents. In addition to the formulas of Isaac Newton and Albert Einstein, there were pages of detailed drawings covered with indecipherable notes and elaborate equations.

"These plans go far beyond the scope of any thirteen-year-old science student," Kathleen said.

"Do you think the kids might have been working on plans for a bomb or some other type of weapon?" Gus asked. "If so, maybe a group of terrorists kidnapped the kids."

"The theories used here are a little too advanced for me," the high school teacher admitted to Detective Kramer. "I'd like to show them to a friend of mine who teaches nuclear physics at the state college."

"I'll make a copy for you."

Two hours later, Kathleen called from her friend's office. "I hate to disappoint you, Mel. But these papers weren't part of a school assignment. This kid must have been playing some kind of game—a game for geniuses only. Either that or he's an aspiring science fiction writer."

"I don't follow you."

"All his notes and formulas are based on strictly theoretical principles; none of them have been proven. Oh, and those plans your partner thought might be for a bomb," she laughed, "they're actually blueprints for a time-travel machine. This kid obviously hoped to be the next Jules Verne or H.G. Wells."

* * *

Once again Kramer questioned Mac Ferguson, and once again Mac had no information to help the investigation.

"I'm sorry, Detective, but since the divorce, I don't get to see as much of my son as I'd like."

"I realize that. In fact, your ex-wife was the one I really wanted to talk to. Mothers usually know more about their children's interests and activities than the fathers do."

"I guess you haven't heard then?" Mac asked, with pain and sorrow keenly etched on his face. "She's had a nervous breakdown. The doctor sent her to a hospital to rest. I'll give you the name and address if you'd like to contact her there; but you might be wasting your time, Detective. The last time I saw her she was completely unresponsive. I don't think she even knew I was in the room."

Later that afternoon an orderly led Detective Kramer to Sally Ferguson's room. At first, the detective did not recognize the missing boy's mother. She had lost close to thirty pounds, and her dark brown hair was snowy white. Clad in a simple linen hospital gown and cheap slippers, she sat in one of the room's two chairs staring sightlessly out into space.

"Mrs. Ferguson, do you remember me? My name is Detective Melvin Kramer. I'm investigating the disappearance of your son."

There was no response. He might just as well have been talking to an empty chair.

"Please, Mrs. Ferguson, I need your help. Marshall needs your help."

Was there a slight movement of the muscles around the eyes, or was it only his imagination?

"Don't you want to help us find Marshall?"

Again, Kramer sensed a reaction when he repeated the boy's name.

"Mrs. Ferguson, did your son play games with the other students at the academy, games in which he would fantasize?"

There was no reply, but Kramer did not give up easily.

"Was he a big fan of science fiction? Did he read H.G. Wells?"

This is going nowhere, Kramer thought.

He was wasting his time. But then, what did it matter? He had no other leads to follow, so he might just as well continue to grasp at straws.

"Did he show any interest in what might happen in the future? Or, perhaps he was curious about things that had happened in the past."

Her sharp intake of breath was unmistakable. Kramer was sure he had stumbled onto something.

"Your son was interested in history, wasn't he?"

Sally Ferguson's breathing became labored.

"Did any of the other boys share his interest?"

The patient's head slowly turned toward the detective. Silent tears began to fall.

She looked him straight in the eye and asked, "What came first: the chicken or the egg?"

Kramer leaned heavily back in the chair and sighed. For a few moments, he had thought he was actually getting through to her. Now he realized that although her lights were on, there was no one home. He got up from his seat and took several steps toward the door.

"Detective Kramer," Sally called to him. "What do you think is likely to happen if, by some miracle, a person was able to go back in time?"

Now it was Kramer's turn to catch his breath. Maybe he had not been wasting his time.

"Just how far back in time are we talking about, Mrs. Ferguson?"

"The 1930s."

While the likelihood of time travel was hard for him to accept, Kramer tried to keep an open mind.

"Assuming time travel was possible, why would anyone want to go back to the time of the Great Depression?"

"Other things were going on in the world while this country struggled with its economic problems."

A chill crept down Kramer's spine.

"What exactly are you getting at, Mrs. Ferguson? What's all this about the chicken and the egg?"

"Let's suppose the children were specifically sought out and recruited by a radical political group."

"What group?"

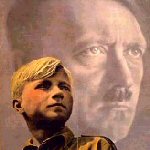

"The Nazis. Or, more specifically, a modern-day version of the Nazis. Hitler believed that children were Germany's future. He never underestimated their capabilities. He always kept in mind his long-range plans for the Third Reich: educate the children, indoctrinate them, mold their young minds and control them. Just look at how organized the Hitler Youth groups were."

"Okay, so some neo-Nazi group locates a bunch of young geniuses, and these kids somehow discover a way to travel back in time. Why? Do they intend to bring Hitler and his henchmen back to the twenty-first century with them? They would be walking anachronisms. I don't think they'd be much of a threat to us."

"You really don't get it, do you? The ability to travel through time is only incidental to the children's true value to the Reich. It was only a means to an end."

"What's the end?"

"What do you think forty-two little geniuses with their computers are capable of doing? If they can find a way to travel through time itself, creating an atom bomb would be like assembling tinker toys."

"But if they succeed ...."

"Oh, they will, Detective. Or, I guess it's more appropriate to say that they already have. That's where the chicken and the egg come in. They succeed and all the events of the past sixty-odd years cease to exist. But look around you. Everything is still the same."

"Then they failed."

"No. There was no way they could fail. The children developed the bomb, but when Hitler used it, he must have set off a chain reaction that resulted in ... cancellation."

"I have no idea what you're saying."

"The bomb goes off and changes the world as we know it today. In doing so, my life, Mac's life and the lives of the parents of the other boys have been drastically altered. The result: by changing the past, the children prevented their own conception and birth."

"But nothing has changed," Kramer argued. "Wouldn't all our lives have been altered if Germany got the bomb first?"

"Yes, but, here's where it gets tricky. Since the children prevented their own existence, they could not have traveled back in time or developed the bomb. So, things go back to the way they were."

"Then where are the boys? Here in our time or in Nazi Germany?"

"I think they're caught in limbo. To you and me and everyone else, time continues on in a straight course. But I think they're traveling in a circle, a sort of holding pattern in time."

"Do you mean they are continually being born one second only to die the next?"

"No, not exactly. They can't die if they were never born. It's like how can a chicken lay an egg if it was never hatched from one itself."

Kramer had had enough of this unsolvable riddle. He was a man who expected questions to have answers, not further questions.

"Mrs. Ferguson, that's certainly an interesting theory you've concocted, but I just don't buy it. I think your son and his classmates are being kept somewhere under lock and key by an unscrupulous group of men who want to exploit their intelligence."

"You're a cop, and like Joe Friday you probably want 'just the facts.' Right?"

Kramer smiled and nodded. Sally got up from her chair and walked to the small night table next to the bed. She opened the drawer, took out an envelope and handed it to the detective.

"Here's a fact, a tangible piece of evidence."

The envelope was yellow with age. It was addressed to Mrs. Sally Ferguson, but there was no return address in the corner. Finally, Kramer's eyes went to the stamp and to the postmark, and he raised his eyebrows.

"I received that letter on the morning I was sent here," Sally explained. "You can go ahead and read it."

Kramer removed the letter from the envelope. It, too, was yellow with age; the paper was brittle and the ink was beginning to fade. The body of the letter was similar to those most boys write home from camp, telling their mothers about hiking trips, campfires, sing-a-longs and cook-outs. But amidst the descriptions of innocent childhood pastimes were darker, more sinister phrases.

Today, Baron von Schirach explained our great destiny as masters of the Aryan race ... We have been working night and day, preparing a birthday surprise for the Führer ... While the other children drill and march and prepare for their future in the SS or the Gestapo, we are studying Professor Otto's CDs on Einstein's experiments relating to the Manhattan Project.

Kramer carefully folded the sheet of paper and put it back in the envelope. After one last look at the Berlin postmark and the photograph of Adolf Hitler on the stamp, he returned the letter to its owner.

"We'll continue to search for your son and the other boys," the detective said stubbornly.

Sally Ferguson, however, had no hope of ever seeing her son again.

Would anyone like to kidnap a black cat with a laptop? PLEASE!