The Missing

Recently, I have been giving a great deal of thought to missing persons cases. There are many children who are abducted either by family members or sexual predators. There are adults—usually women—who fall victim to foul play. There are others who disappear of their own accord, often to escape the demands of domesticity or to avoid problems with the law.

All these disappearances I group under the general heading of the explainable missing. It is the other group, the unexplainable missing, that worries police detectives. These are individuals who seem to literally vanish off the face of the earth. I don't mean people like Jimmy Hoffa, Judge Crater, the people onboard the Mary Celeste or Amelia Earhart and her navigator, Fred Noonan.

No, I'm referring to bizarre cases like that of Patty Stowe. Don't bother to google the name, for the case, which came about in the wake of the 9/11 attacks, received no press coverage and was never solved. Her file lies buried on the uppermost shelf at the back of the unsolved cases room.

Patty was a seven-year-old girl who went into the ladies' room at a neighborhood fast-food restaurant while her father waited outside the door. The small lavatory had been vacant when the girl went inside. The father and three women standing in line behind him all testified that the little girl entered the windowless, empty bathroom through the only door and never came out again. When Patty did not answer her father's calls, the restaurant manager unlocked the door with his pass key. To everyone's astonishment, the room was empty.

"But I saw her walk in there with my own eyes!" exclaimed the woman standing immediately behind the child's distraught father.

The woman, who just happened to be the wife of the town's chief of detectives, was considered an irreproachable witness.

The police were called, and an officer went over every inch of the room, searching for a concealed opening in the walls, floor or ceiling.

"The place is tight," he pronounced after a thorough examination. "Not so much as a mouse hole. If that door was shut, no one could have gotten out of here."

Had it been only the child's father waiting outside the restroom door, suspicion would naturally have fallen on him. However, the chief of detectives' wife and two other pillars of the community all told the same story.

For a week, police officers and volunteers scoured the county for any sign of Patty Stowe. The little girl's photograph appeared briefly on the local television news program and was posted in shop windows and on telephone poles throughout the eastern half of the state, yet no one came forward, and no traces of the girl were found.

This strange case has haunted me for years. Although I was a young rookie fresh from the police academy and assigned to traffic duty at the time of Patty's disappearance, I put in many hours searching for the child. Yet despite the crime-solving experience I've accumulated since then, I am no closer to understanding what happened to the girl.

Thankfully, a puzzling case such as that one is exceedingly rare, but I occasionally ask myself if there are people gone missing that no one has ever reported. What about those who live on the fringe of society and those who live alone with no close friends or family? One of them could disappear, and no one would notice. Certainly it is likely in the case of the homeless. There might be any number of unexplainable missing persons, except no one knows—or cares—that they are missing.

* * *

Just as a blizzard begins with a few scattered snowflakes, the recent wave of disappearances that has plagued our society began with isolated incidences. An eleven-year-old boy in Williamsport, Pennsylvania, said goodbye to his teammates after baseball practice, got on his bicycle and pedaled home. Although his bike was found in his parents' driveway, there was no sign of him. An Amber alert was issued and an exhaustive search followed, all to no avail.

That same day, an accountant boarded a commuter train in New York City. En route to his home in Darien, Connecticut, he spoke to his wife on the cell phone. She was waiting to pick him up at the station, but when the train arrived, he was nowhere to be found.

Which of these two individuals vanished first is not known since the exact time of either person's last sighting could not be pinpointed.

Only two days after the disappearance in Pennsylvania and New York/Connecticut, three high school students stopped at a drive-thru carwash on their way home from the beach. They were seen sitting inside a Toyota Camry when the car went on the conveyor, but minutes later the car sat empty at the exit.

When I received the call from the owner of the business, I was skeptical. No one disappears from a carwash, especially when there are four cars waiting in line to enter at one end of the tunnel and staff members waiting with towels at the other. But having been familiar with Patty Stowe's case, I went to the scene with an open mind.

Surprisingly, when I arrived at the carwash, I discovered that everyone who had been there at the time the Camry went through the line was still there. Usually, potential witnesses don't want to get involved. Apparently, these witnesses wanted to know what had happened as much as I did.

"There's no way those kids could have gotten out of there without my seeing them," insisted the man who had been directly behind the Camry.

"I've been through this carwash myself," I argued. "There are times when the water pressure and the movement of the brushes don't allow any visibility through the windshield."

"Then where did they go?" he argued back.

"That's what I'm here to find out."

I turned to the attendants.

"Is there any place inside the carwash these kids can be hiding?"

The attendant in charge stepped forward.

"As soon as I saw there was no one behind the wheel of the Camry, I shut down the conveyor system and turned off all the machines. The staff searched the tunnel, and I opened the trunk from inside the car, but we couldn't find anyone."

I saw no reason to leave the car at the end of the conveyor and gave the attendant permission to park it off to the side. He then locked the car and handed me the keys.

While my partner questioned the remaining witnesses, I ran the Camry's plates through the department of motor vehicles. The car was registered to a family that lived less than a mile from the carwash.

"Let's go see who's home," I told my partner after he was through with his questions.

Not surprisingly, the mother's reaction to the news was one of fear.

"Andy's always been such a good boy. What could have happened to him?" she cried.

"Maybe your son's playing a practical joke," I offered. "He might be nearby getting a good laugh out of all this."

The woman acted as though I'd slapped her across the face.

"My son isn't one for practical jokes! He's an honor student."

"Would you mind if we had a look around his room? There might be something there that could tell us what's going on."

I had expected her to protest or at the very least to ask if we had brought a search warrant with us, but she immediately gave us her consent. As my partner sat with the distraught mother, taking down the names and addresses of Andy's friends, I went down the hall and into the boy's bedroom.

It was no different from other teenagers' rooms I had seen: stereo, computer, television set, desk, dresser. There was a Green Day poster on the wall behind the bed, and as I looked through the missing boy's closet and dresser drawers, I had the eerie feeling that Billie Joe Armstrong's darkened eyes were watching my every move.

"Anything?" my partner asked after we left the house.

"Nah. You?"

He shook his head.

"His mother says he's a good kid who never gets into trouble."

I chuckled.

"You know how many times I've heard that?"

"I know. There are no bad kids; just blind parents."

By evening, we knew the identity of the other two students in the Camry. Like the driver, they were supposedly well-behaved kids who had never gotten into trouble.

Days passed with no sign of the teenagers. Three sets of parents demanded we find their missing children, but we didn't have the slightest idea of where to look.

* * *

The week after the odd disappearance at the carwash, a week in which I worked more than sixty hours trying to find the three missing high school students, I took a Sunday off to spend with my family. My wife, daughter and I went out to breakfast and then to the local mall, where I handed over my credit card with only minimal complaining.

That afternoon, my son and I retired to the family room—what my wife called the man cave—to watch the Yankees-Red Sox playoff game. During the top of the fourth inning, the bases loaded with Yankees, the Red Sox hurler worked the count to three and two. There was one out, and my son and I prayed for a double play. Suddenly, the screen went black.

"What the ...?"

I turned the channel. A movie was playing on HBO.

"It's not the TV or the cable," I concluded. "It must be the station."

I turned back to the game, which was still blacked out. We waited, anxious to know if the Sox pitcher had worked his way out of trouble.

Meanwhile, an engineer at Fox television placed a call to the crew at Fenway Park. The phone rang, but no one answered. He next tried the cell phone of his chief cameraman. Again, there was no response. He hung up and called the Boston helicopter pilot, who reported on traffic conditions and periodically flew over the stadium to take aerial shots of the game, and asked him if anything was out of the ordinary at Fenway.

"I'm nearing the stadium now," the pilot shouted over the noise of the helicopter. "I'm about a block away. Everything looks all right from here. No police cars. No ambulances. Considering the fact that it's a playoff g—Holy shit!"

"What's wrong?"

"I don't freaking believe what I'm seeing!"

"Tell me! What do you see?"

"An empty stadium."

"What do you mean by empty?"

"No people: no fans, no ballplayers, no vendors. The parking lot is jammed with vehicles, but there's not a solitary soul inside Fenway."

* * *

The event sent shockwaves around the world. It was a disaster that ranked among the sinking of the Titanic and the attack on Pearl Harbor. Not only did it result in the loss of tens of thousands of lives, but it was also the end of the New York Yankees and the Boston Red Sox.

It wasn't a matter of just unfamiliar faces on milk cartons or posters. This time some of America's most beloved sports heroes were among those who disappeared. Baseball fans as well as the friends and family members of the missing made a pilgrimage to Yawkey Way. Fenway Park became a memorial shrine to the victims, with photographs, floral pieces, baseball cards and candles encircling the stadium.

The Boston Police Department was overwhelmed by the number of missing persons cases. Both the Massachusetts State Police and the FBI were called in to help, but neither organization had much to offer. Homeland Security and the CIA were quick to investigate any possible threats to national security. Religious groups also had their representatives in the area: priests, ministers, rabbis, muftis, shamans and pagan priestesses. Psychics and mediums flocked to the scene to lend their special skills to the search, while fundamentalist Christian groups claimed the disappearances were the work of the devil.

I began to take a second look at my own case. Could whatever had caused some forty thousand spectators, employees and ballplayers to disappear from an open stadium in the middle of a major city also cause three high school students to vanish from a Toyota Camry in an automated carwash?

Through my contacts at the state level, I was put in touch with a member of a newly formed task force that was to investigate the Fenway Park incident. I explained to her that I was investigating a similar unexplained disappearance, although on a much smaller scale. My impeccable record as a police officer (and the task force's total lack of experience in such disappearance cases) opened doors for me that normally would have been kept tightly shut.

Surprisingly, I was given permission to go to Fenway and assist in the search for clues. At the gate, I was joined by a novice FBI agent, one from the lowest rung of the task force ladder. As we walked through the empty stands, my mind became filled with questions and observations.

"There are no clothes here, but I do see a large number of camera bags, backpacks and women's purses."

I thought a moment, and the explanation became clear.

"Everything on the people—clothes, wallets, cell phones, jewelry—disappeared with them. The camera bags, backpacks and handbags were on the ground or under the seats. Wherever these people went they literally took only the shirts on their backs."

As we walked, I noticed a pair of binoculars lying in an open camera case. I picked them up and scanned the stadium.

"Nothing much to see," Rossi said. "Just more of the same we found in this section."

I turned the binoculars to view the old manual score board on the Green Monster. It still showed a three-two count and one out in the top of the fourth inning.

As a cop, I've seen nightmarish sights, from fatal car crashes to brutal murders, and learned to take them in stride, but for the first time in my career tears formed in my eyes. There would never be an end to the inning or to the game. The baseball commissioner had announced that all remaining post-season games, including the World Series, were to be cancelled. The following spring the Yankees and Red Sox would return with new rosters.

Not wanting the FBI agent to see my reddened eyes, I kept the binoculars to my face, pretending to still be looking for clues. Then, suddenly, I focused on a spot on the Green Monster.

"What's that?" I muttered.

"What's what?" Rossi asked.

I handed him the binoculars.

"What's that above the America League standings?"

"I don't know. I can't see it that well, even with binoculars."

"Well, let's go down to the field and have a look," I suggested.

"Do you really think that's necessary? What are you likely to find on the wall?"

"We won't know until we go down and check it out."

The two of us walked out onto the field through the dugout. Even standing on the warning track, it was hard to discern the markings on the wall above us. It was a good thing I had taken the binoculars with me. I raised them to my eyes and focused.

"Damn!" I exclaimed.

"What is it?"

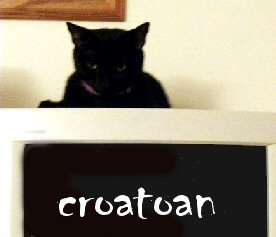

"It's a word carved into the wall: croatoan."

I could tell from the blank look on Special Agent Rossi's face that he was unaware of the significance of the word.

"Did you ever read about the Lost Colony of Roanoke?"

"No," he admitted. "History was never one of my favorite subjects."

"To make a long story short, Governor John White sailed to England for additional supplies. When he returned to Virginia, he found the colony deserted. The ship's crew searched for the colonists, but there was no sign of them. All they could find was the word croatoan carved into a tree."

"I'll bet some damned kid snuck into the stadium and put that word there as a joke."

"Hardly," I said. "That's at least twenty-five or thirty feet above the ground. Someone would need a ladder to reach that area. Then, think of how much time it must have taken to carve a word into the wall. This isn't wood. It's hard plastic over concrete and tin. No, if it was a vandal with a sick sense of humor, he would have simply taken a can of Krylon and spray painted croatoan on the wall."

* * *

The next day I again visited the home of the missing boy who owned the Toyota Camry. Andy's mother was anxious for any word of her son's whereabouts. Unfortunately, I had no news for her.

"Can I look at the car again?" I asked.

"Certainly."

I knew the forensics team had gone over every inch of the Camry before releasing it to the boy's parents; however, the CSI techs were only interested in fingerprints, blood spatters and hair, dirt and fiber samples.

The Toyota was locked in the garage. No doubt the parents would keep it there for some time, hoping its owner would return home. After carefully examining the outside of the car, I took a flashlight out of my pocket and examined the interior. I found nothing out of the ordinary. Finally, I went around to the back of the vehicle and opened the trunk. There it was, carved in the plastic above the rear driver's side wheel: croatoan.

"I'll be a son of a bitch! These disappearances are connected!"

After leaving the missing boy's house, with assurances to the weeping mother that I would call her if I heard anything at all about her son's whereabouts, I returned to the police station. I immediately phoned the police in Williamsport.

While I waited for someone in Pennsylvania to check on their missing boy's bicycle, I went downstairs to "the dungeon," the name affectionately given to our records room, and headed directly to the cold case area. I found Patty Stowe's file, which was packed with photographs of the women's restroom, and took it upstairs to my desk. When I opened the folder, the girl's dark brown eyes stared up at me imploringly from her school picture.

"You would probably be married with children of your own by now, if only ...."

I struggled to keep my emotions in check. It wouldn't do any good if I allowed myself to think about the life the poor child might have had. Instead, I rifled through the crime scene photos. Fortunately, nearly every inch of the room had been photographed. Although I looked over these pictures with a magnifying glass, I couldn't find any clue. It wasn't until I came upon a photograph of the bathroom sink that I found the proof I was searching for: just below one of the soap dispensers, someone had carved croatoan into the tile.

By the time the Williamsport police informed me of what they'd found on the missing boy's bicycle, I had already come to the conclusion that all these cases were related.

* * *

When I returned to Boston with photographs of the bathroom and bicycle in hand as evidence, I was introduced to a man much higher than Special Agent Rossi on the task force ladder.

"The lost colony of Roanoke? Are you telling me these disappearances go all the way back to 1590?" the senior agent asked skeptically.

With the years I spent as a beat cop and then a detective, I've learned to read people. I knew the Harvard-educated, government-trained man across the desk from me would never buy any explanation that even hinted of the supernatural.

"Not necessarily." Then, knowing exactly what buttons to push, I continued, "It could be that some politically motivated group is responsible for what went down in Fenway. Someone in that group—obviously a student of history—decided to pick croatoan as a calling card."

At the mention of a possible terrorist threat, the agent's eyes glistened with excitement. He reached across his desk for a pen and scribbled a name on a yellow Post-it.

"I want you to go talk to this woman. She's a history professor at Harvard. Find out all you can about the Roanoke colony. In particular, I want to know anything that might cause a terrorist to remember that word and use it while committing the most heinous act on American soil since the 9/11 attacks."

"I'd be glad to help out," I said, "but I don't have too much spare time on my hands. I'm a police detective, and I can't just call in sick, especially when I'm trying to solve the case of the missing teenagers in the carwash."

The agent brushed my objections aside.

"Don't worry about that. As of now, you're a member of my task force. Besides, if these cases are all connected, as you believe, this is your best chance of finding out what happened to those high school students."

Having gotten exactly what I wanted, I tried to hide my smile of satisfaction as I walked out the door.

"You've still got it, Detective," I congratulated myself. "You had that federal clown playing right into your hand."

* * *

I had imagined a college history professor as having graying hair pulled back in a severe bun, to have the hemline of her skirt below her knees and the bodice of her blouse primly buttoned up to her throat. So when I entered the university office and saw a curvaceous young blonde sitting behind the desk grading papers, I erroneously assumed it was a teaching assistant. Either that or a Barbie doll come to life.

"Where's the professor?" I asked.

"I'm the professor," she replied.

She saw the surprise on my face and laughed.

"Perhaps I'd look more convincing if I put my glasses on."

I introduced myself and flashed my newly acquired task force identification.

"So, you're investigating the disappearances at Fenway?"

It was more statement than question.

"How can I help you?"

"I'd like to know about the lost colonists at Roanoke."

I braced myself, waiting for her inevitable display of skepticism. Surely no college professor would believe there was a link between two events that happened more than four hundred years apart, but I was wrong.

"You think there's a connection between what happened in Roanoke and what happened here in Boston?"

"I didn't say that. I'm just investigating something I found written on the Green Monster."

I took a photograph out of my shirt pocket and handed it to her.

"Croatoan. It's unbelievable!" she exclaimed.

I decided to use the same argument with her as I had used on the FBI.

"I'm sure some political group is using the word as a calling card. I don't actually believe the cause of the disappearances is the same in both cases."

"Don't be so sure, Detective."

I was stunned by her unbiased consideration of such an improbable explanation, but after my initial surprise, I was delighted.

"Do you think these two events might be related, professor?"

"When I was in college, I got involved with a group of fellow students that were into paranormal investigations," she explained. "I'm sure you've seen similar groups on television. They go into old buildings with night vision goggles and all sorts of high tech gadgets to see if they can find any evidence of ghosts."

"I've seen a few episodes, but I never gave them much credence," I admitted.

"Neither did I at first, but after going on a few outings with them, I wasn't so skeptical."

"And what about Roanoke?"

"About eleven years ago we went into an old restaurant that housed a speakeasy during Prohibition. It was believed that a tragedy had occurred there back in the Twenties. A party was held on the premises with jazz music, dancing and bootleg whiskey. One of the young men left to go buy cigarettes at a store about five miles up the road. When he returned, he saw that everyone else had vanished."

"Was there an official investigation into the disappearances?" I asked.

"Yes, but the case was never solved. Police believed it was a gangland hit. They were sure the bodies were buried under the new highway that went through the town a month later."

"But you don't believe that."

"While my friends were making voice tapes and taking EMF and temperature readings, I did a little exploring. Most of the place had been renovated over the years, but the bar was still the same one that was there on the night of the party. I examined it closely. On the underside, I found the word croatoan scratched into the wood."

The professor took her keys out of her handbag, and after unlocking a drawer in her credenza, she removed a large accordion file that was brimming with newspaper clippings and notes written on yellow foolscap. I literally held my breath with anticipation as she searched the contents.

"I've discovered similar disappearances," she said, handing me several typed pages that were held together by a polypropylene folder. "This is a brief summary of my research. In all the entries marked with a star the word croatoan was scratched into a surface, usually wood, nearby."

Looking at the dates and the number of incidents, I knew I had only touched the tip of the iceberg with my own brief investigation.

"There are more," I said. "Three high school kids recently disappeared in a carwash."

"I heard about that case," the professor said. "And it fits the pattern?"

I nodded.

"You have what ... a dozen pages here? That's a lot of people to simply vanish," I observed.

"And that's just the ones we know about. What about the ships that have gone down at sea over the centuries? How do we know the crews and passengers didn't vanish before the ships did? Take the Mary Celeste, for instance. There was never any sign of the missing captain, his family or the crew. And there's no reason to believe this all started with Roanoke. This creature could have been in existence ever since man learned to stand on two legs."

"Creature? What creature?"

"The creature that has been devouring men, women and children without leaving a trace."

"Hey, wait a minute, professor!"

"Surely you don't believe these disappearances are the work of a terrorist group?"

"I admit there's something out of the ordinary going on here, but a supernatural creature?"

"Not supernatural. It's obviously part of nature and part of man's history."

"Then why hasn't anybody ever seen it?"

"I can't see all the television or cell phone signals travelling through the atmosphere, but there's no denying they're there."

"Oh, so it's an invisible creature? Well, that makes all the difference," I said sarcastically.

"I should have known that being a policeman you wouldn't be open-minded."

Her observation was ironic since I had come into the office expecting her mind to be closed.

"I'm sorry," I said, and her anger quickly passed. "Why would the creature leave a calling card? Why not just eat and run, so to speak?"

"My best guess is that it's marking its territory, as many known animals do."

"Kinda like lifting its leg and peeing on the furniture?"

"If it were a dog, that's exactly what it would do," she said with a smile.

"You seem to have given this theory a great deal of thought. Since you believe it's alive, can you think of any way to destroy it?"

"No," she admitted reluctantly. "However, it's imperative that we do destroy it—and soon."

"Why?"

"Because in the past it only fed on individuals and relatively small groups of people. To my knowledge, it never took on anything as grand in scale as what happened in Fenway Park."

"What do you suppose it means?"

The professor's explanation chilled me to the bone.

"I fear the creature is consuming more than normal because it is about to reproduce."

* * *

This is the point, I'm sure, where you expect me to turn into Hercule Poirot and unmask the identity of our antagonist and describe in detail how we managed to destroy it. Unfortunately, I can't oblige.

Despite the impressive evidence the esteemed professor and I compiled, we were unable to convince anyone else of the existence of a centuries-old creature—or, more likely, one of a long line of such creatures.

"I don't see what further proof they need," I complained to the Harvard historian.

"Even if we had photographs, film clips and the creature's birth certificate," the blonde declared facetiously, "no one would believe us. The only way anyone will be swayed to our opinion is if they witness the creature feeding on an unsuspecting human—and, even then, a majority of witnesses would deny the evidence of their own eyes."

Needless to say, law enforcement authorities, the news media, government agencies and academic community refused to listen. The professor and I were laughed at, ignored, insulted and ridiculed. In fact, the only people who paid heed to our claims were the same people who insisted aliens inhabited Roswell, New Mexico, camped beside Loch Ness to catch a glimpse of its fabled monster and believed the moon landing was faked at a Hollywood studio. Not even the supermarket tabloid newspapers were willing to give our explanation of the disappearances fair coverage. Instead, we became the laughingstock of the nation, the butt of late night talk show hosts.

* * *

From my retirement home in Florida, I look back over many years at the events I've described in this narrative. I am now just weeks short of my hundredth year on earth, and although my body isn't anywhere near as strong as it once was, my brain is as sharp as ever.

Over the past several decades, I've continued to keep detailed records on missing persons. The majority of them—thank God!—fall under my category of explainable missing; only a handful I classify as unexplainable.

The strange disappearances at Fenway Park were never solved. That doesn't mean the case faded from people's minds. It ranks up there with the Kennedy assassination as a subject for conspiracy theorists and armchair detectives. It is the subject of dozens of movies and television shows as well as hundreds of books and magazines, both factual and fictional in nature.

In addition, there are thousands of Internet websites dedicated to the theories of what really happened that October day in Boston. One of them, very well-written by an unnamed, retired history professor, claims there is an ages-old creature living among us who feeds on unsuspecting humans. This is considered by the vast majority of "sane" people to be the most outlandish, gruesome and implausible theory of them all.

In retrospect, the theory I personally prefer is that the disappearance was the result of a terrorist attack by either a foreign or domestic political group—the exact means known only to the federal government. Since no other large groups have been targeted, it is assumed the Department of Homeland Security neutralized the threat. This is the theory I like most because it is the one that helps me sleep at night. I can rest peacefully knowing my children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren will not wind up some ancient creature's breakfast or midnight snack.

But when I wake in the wee hours of the morning, I often imagine unseen creatures, perhaps living in one of H.P. Lovecraft's alternate dimensions, who are patiently waiting until such time in the future that they will gorge themselves and reproduce.

Hopefully, by that time, I and my progeny will long be in our graves.

This isn't funny, Salem. Now I have to buy a new monitor!