The Mourning Quilt

After her mother and father died of smallpox in the untamed territory of western Massachusetts, thirteen-year-old Hannah Miles was sent back east to live with her father's elder sister, a seamstress, in Boston. Viola Conant was glad for the orphan's company. A lonely widow with no children of her own, Aunt Viola soon grew to love her niece like a daughter.

It was kindly Mrs. Conant who taught the teenage girl to sew. Growing up in the mid-nineteenth century, Hannah had learned at an early age how to mend clothes, but her rudimentary skills centered on needlework that was practical and functional, not ornamental. Aunt Viola taught her the finer arts of embroidery, needlepoint and quilting. She also taught her how to sew fashionable clothing for Boston's wealthier women.

"Your stitches must be small and uniform in size," the experienced seamstress instructed. "And when you make a seam or a hem, the stitches must be so small as to seem invisible."

For four years, the blossoming young woman practiced the trade until, at seventeen, she was nearly as skilled with a needle and thread as her aunt was. During those years the two women enjoyed a close relationship, but Aunt Viola realized it was in her niece's best interest to marry.

There was no lack of young men in Boston, and Mrs. Conant critically viewed each eligible bachelor she encountered as a possible husband for Hannah. However, not one of them measured up to the older woman's high expectations. Hannah feared she might die a spinster, but Aunt Viola put her faith in providence, believing that the right man would come along one day.

That day began with the arrival of the morning post.

"Who do you know in Philadelphia, Aunt Viola?" Hannah asked as she handed a letter to her aunt.

"No one."

Her curiosity piqued, the widow ripped open the envelope with her fingers, without taking the time to look for the letter opener. Her eyes immediately went to the signature at the bottom of the page.

"Why, it's from young Henry Lansford," she announced with joyful surprise.

"Who's he?" her niece asked.

"He's the son of my late husband's cousin."

Aunt Viola quickly scanned the body of the letter.

"How wonderful! Young Henry will be coming for a visit. Apparently, he's been attending school in Pennsylvania, and he's going to stop in Boston on his way home to Puritan Falls."

Hannah had anticipated only an enjoyable break in the usual routine, a brief visit from an old family friend that would entertain her and her aunt and then fade into a pleasant memory. She had no inkling that the young man from Puritan Falls would change her life forever.

The day Henry Lansford, Jr., was to arrive in Boston, Aunt Viola made quite a fuss. The house was scrubbed clean and a delicious meal prepared. She also took an unusually long amount of time dressing and fixing her graying hair. Hannah was amused at her aunt's acting like a schoolgirl.

Meanwhile, the young woman herself did little to enhance her looks. Although she wore one of her Sunday dresses, she combed her hair back into a simple chignon rather than go to all the trouble of curling it. When she opened the front door that fateful afternoon, however, she wished she had taken more pains with her appearance.

"You must be Mrs. Conant's niece," Henry said when he saw Hannah.

The young man's handsome face took her by surprise and left her temporarily speechless.

"Henry!" Aunt Viola exclaimed as she brushed past her niece in order to hug her guest.

After receiving an affectionate kiss on the cheek, she took the young man by the arm and ushered him over the threshold.

"You've met my niece?"

"Only briefly," he replied. "Perhaps you will properly introduce us now."

"Certainly. This is my late brother's daughter, Hannah Miles. What a blessing the dear girl has been to me."

"I'm delighted to meet you," Henry said with a chivalrous bow.

Aunt Viola was not oblivious to the looks that passed between the two young people or to the maidenly blush on her niece's cheeks. Nor was she displeased by them.

"How is your father?" the widow asked after pouring the visitor a cup of tea.

"Fine. At least that's what he tells me in his letters. I haven't seen him since Christmas."

"And how was your time in Philadelphia?"

"Extremely busy, I'm afraid. Unfortunately, I was so occupied with my studies that I had no time to see the sights of the city."

"What did you study?" Hannah asked shyly, trying to join in the conversation.

"Medicine," he answered, his eyes lingering on the young woman's fair features.

"Following in his father's footsteps," Aunt Viola explained. "Henry's father is a doctor, too."

"Will you be working with your father?" the girl inquired.

"I hope to, but one never knows what the future holds for us. I fear that if Mr. Lincoln gets elected ...."

Henry saw the sadness in Hannah's blue eyes and immediately felt contrite.

"Forgive me. I don't want to talk of unpleasant things in such delightful company."

"This one's a charmer like his father, too," Aunt Viola laughingly declared, effectively brightening the conversation and returning the smile to her niece's face.

Although Henry was to have returned to Puritan Falls the following day, he invented a number of excuses for remaining in Boston. Three weeks later, he faced the inevitable: he had to go home.

"We're going to miss you," Hannah told him when he stopped at the house for a farewell dinner.

"Are you really?" he asked, encouraged by her words.

"Yes. My aunt and I enjoy your company very much."

An awkward silence followed. Aunt Viola was in the adjoining building, closing up her seamstress shop for the day, and the two young people were alone in the parlor of the house.

"Maybe I ought to see if my aunt needs my help," Hannah announced, wanting to extricate herself from the uncomfortable situation yet, at the same time, desperately wanting to remain near Henry.

"Don't go," the young doctor urged. "We have so little time left. Let's not ...."

A moment later his lips found hers.

When he finally returned to Puritan Falls nearly a month after that impetuous first kiss, Henry Lansford, Jr., was accompanied by his bride and her widowed aunt. The newly married young woman from Boston instantly fell in love with the picturesque little village on the Massachusetts coast. The Lansford family home on Danvers Street was warm and comfortable, and her father-in-law was a dear man, whom she soon grew to love very much.

Hannah's happiness was made complete when, in less than six months from her wedding day, the newlywed bride learned she was with child.

* * *

"What's that you're making?" Henry inquired one evening when he returned home from visiting a sick patient and found his wife sitting in front of the fire, cutting shapes out of fabric.

"A quilt," she replied.

"For the baby?"

"No, it's a cemetery quilt or, as my mother called it, a mourning quilt."

Henry frowned.

"Why? Did someone die?"

"No," Hannah reassured him with a smile. "I'm starting what I hope will be a family heirloom, a quilt that will be passed down to our children, and to their children, and so on."

Then she put aside her fabric and scissors and picked up a pencil and a piece of paper.

"Look," she said, drawing a simple illustration. "The center squares represent a cemetery, surrounded by a fence. Along the border, it's customary to appliqué coffins. The names and dates of birth of the members of the family are embroidered on the coffins. When someone dies, his or her coffin is removed from the border, the date of death is embroidered on it and the appliqué is relocated to the center of the quilt—inside the cemetery."

"Isn't that rather morbid?"

"No more morbid than recording births and deaths in a family Bible."

"I suppose you're right," Henry said, sitting down in the wing chair opposite his wife's.

Both he and Hannah enjoyed their shared moments in front of the fireplace. The day's work was done, and they could enjoy each other's company with no interruptions.

I hope it'll always be like this, Hannah thought wistfully, returning to her quilting as her husband picked up a book by Charles Dickens and began to read aloud.

Regrettably, Hannah Lansford's domestic bliss was shattered not long after she and her husband celebrated their first Christmas together.

In January 1861 the Southern states seceded from the Union and formed the Confederate States of America. President Abraham Lincoln was determined to hold the Union together, but on April 12 shots were fired at Fort Sumter in Charlestown Harbor, and the Civil War began.

"Lincoln has called for volunteers to fight," Henry informed his wife during dinner one evening.

"I hope you have no plans of joining the army," Hannah said anxiously.

"No ...."

"You don't sound very sure of yourself."

"I'm not going to fight," he declared, "but my country needs my services as a doctor."

"You're not seriously considering volunteering!" Hannah cried.

"I fear that there will be many casualties," he explained, "and not nearly enough doctors or nurses to care for the wounded."

"But I want you here by me, especially with the baby coming."

The pleading look in his wife's blue eyes tore at Henry's heart.

"All right, my darling," he agreed. "I shall refrain from volunteering."

"Good!"

"But I can't promise that, should I be needed in the future, I won't change my mind."

"There's no need for you to promise. Everyone knows the war won't last long."

Henry turned his head toward the window to hide his frown from his wife. He did not share the generally held opinion that the fighting would soon be over. On the contrary, he anticipated a long and bloody war ahead.

Three months passed, and the hostilities continued. Meanwhile, both Hannah's quilt and her pregnancy advanced.

"I should be finished sewing about the same time the baby comes," she said, threading her needle in the light of an oil lamp. "My aunt and some of the women from the village are going to help me with the batting, and Phoebe Reynolds is going to let me borrow her quilting frame."

"How is Mrs. Reynolds?" Henry asked. "I haven't seen her since I treated her sprained ankle."

"Anxious, as to be expected. Her son, Matthew, has joined the army."

Henry was surprised at the news.

"Matthew Reynolds is in the army? I didn't realize he was old enough to serve. You know, my father delivered him."

"And you will deliver our child."

Her husband did not reply; he sat staring out the window in silence. The news of the Union's defeat at Bull Run had strengthened his convictions about the war and his determination to volunteer.

"Henry, you will be here to deliver the baby, won't you?"

"Hannah, I already told you, I can't make any promises. If the war ...."

"No! I'm due in a month. I won't have you going off to war and leaving me to have the child by myself. Now, I want you to promise that you'll be here for the delivery."

A month. A lot of innocent men could die in a month, men like Matthew Reynolds, for instance. Still, Henry could not desert his wife when she needed him most.

* * *

Hannah, Aunt Viola and four other women sat around the quilting frame, putting the final touches on the mourning quilt. Phoebe Reynolds, understandably, had not joined them that evening since the sight of the fabric coffins was a painful reminder that her son was risking his life for his country.

Aunt Viola attached the coffin appliqué with her own name and date of birth onto the border, next to the one marked for Henry Lansford's father. Two coffins, representing Hannah's parents, were already placed in the center cemetery.

"This is the last one," Hannah announced, placing an unadorned piece of black fabric between her and her husband.

"No name?" one of her neighbors asked.

"I don't know the name yet," she replied, laying her hand on her swollen abdomen. "I don't even know if it's a boy or a girl."

"Tea anyone?" asked Mrs. Lowell, who had finished sewing.

"I'd love some," Aunt Viola replied. "Hannah?"

"I'll have some as soon as I ...."

A sharp pain took her breath away.

"Is it the baby?" her aunt asked excitedly.

The expectant mother nodded her head.

"Here, let me finish the quilt for you," Aunt Viola offered.

"Thank you, but I'd rather do it myself."

Before the grandfather's clock in the hall could strike another hour, Hannah's mourning quilt was completed, and before the next day dawned, Ethan Lansford was born.

The following afternoon Hannah cradled her newborn son in her arms, marveling at the tiny fingers on his hand.

"They're all there," Henry laughed. "Ten fingers, ten toes."

"My prayers have been answered."

"Yes, you're both in perfect health."

From the tone of her husband's voice, Hannah knew what would come next.

"We still need you here," she objected. "What if the baby should become ill?"

"Darling, I promised I would stay here with you for the delivery, and I did. I can't shirk my duty any longer."

Tears brimmed in Hannah's eyes.

"Can't you stay for just a few more days?"

"Each day, each hour, could mean someone else dies from lack of medical care."

Hannah knew she was being selfish, but she hated to see her husband leave. Why couldn't some other doctor, one without a wife and child, go in his place?

"I suppose nothing I say will change your mind?" she asked.

"Do you think I actually want to go, to leave you and Ethan? But it's my duty, damn it!"

"Then you must go," Hannah relented. "But try not to get shot."

"I'll try," he laughed.

* * *

Hannah missed Henry terribly. Aunt Viola was at hand to help out with the baby, but she was a poor substitute for a husband. Still, her aunt did her best to make the evenings less lonely. The two women would sit in the parlor every night after Ethan fell asleep and sew garments, which were then donated to war widows and orphans. Sometimes they were joined by other women in the neighborhood, including Phoebe Reynolds.

While they sewed, the women would often discuss the news of the war, most of which they learned through letters from loved ones serving in the army or navy.

"Henry tells me Matthew has expressed an interest in becoming a doctor," Hannah told Phoebe.

"I'm not surprised," the boy's mother replied. "He fairly idolizes your husband."

"The feeling is mutual. Henry always writes of the fine young man Matthew has become."

It was much more pleasant to speak of the close relationship that had developed between the men than to discuss the growing number of losses in the army. Still, in talking about the people of Puritan Falls such unpleasant subjects did come up.

"I saw Mr. Bridges today," Aunt Viola said during a lull in the conversation.

"How is he doing?" Hannah asked. "I haven't seen him at church lately."

"Not good; I'm afraid. He lost his son. It was dysentery, I believe."

"Henry says that camp fever and dysentery kill as many men as the Confederate Army does, perhaps more."

"It'll be a miracle if any of our sons and husbands come home," Phoebe declared with a sob.

"Oh, no, you mustn't feel that way," Aunt Viola said, dropping her sewing to comfort the distraught mother. "You must have faith that God will look over our loved ones."

Phoebe, a deeply religious woman, wiped her tears and said, "You're right. It's not up to us to question His plan."

Hannah nodded her head in agreement.

"God's will be done."

Before the war was finally over, however, she would come to believe God's will a heavy burden to bear.

* * *

In September 1862, while many people were mourning the loss of more than three thousand men at Antietam, Hannah lost her father-in-law. Not only did she have to make the funeral and burial arrangements, but she was also the one to inform her husband of his father's death.

Aunt Viola and I were with him at the end, she wrote. It should give you comfort to know he went peacefully.

Would it really give him comfort? Hannah wondered, as she signed her name to the bottom of the letter. Henry had not even known his father was sick. The news was bound to be devastating.

That night, after the funeral guests went home and Aunt Viola and Ethan were both sleeping soundly, Hannah took her mourning quilt down from the bedroom wall and began to rip out the delicate stitches around the coffin that bore her late father-in-law's name. After the appliqué was free, she embroidered the date of his death beneath his birth date and attached it to the cemetery squares in the center of the quilt, placing it to the right of the coffin with her mother's name on it.

"God willing, the next time I alter this quilt it will be to add the birth of another child."

Sadly, such was not the case.

In December 1862, just three days after Christmas, Aunt Viola died quietly in her sleep.

The doctor from Copperwell claimed her heart gave out, Hannah tearfully wrote her husband. With your father and my aunt gone, the house seems empty. I pray this war ends soon and you return to me. I miss you so much.

Not a word was written in the letters by either husband or wife about the battle of Fredericksburg, which proved to be another blow for the Union. Neither wanted to put into words the fear that not only was the North losing the war, but there was also no end to the fighting in sight.

For the next six months, in their letters the couple spoke only of happier days and future plans. And, of course, Hannah kept her husband informed of all Ethan's milestones.

I, too, will be glad when the war ends, Henry confessed. I long to be with my family again despite the fact that my little son will not even know me when I return.

He will get to know you, his wife wrote back, and he'll come to love you and be proud of the sacrifices you made for your country.

Although Hannah's words temporarily eased her husband's fears, the war was taking its toll on him. Henry had volunteered for the army in order to save the brave men who were wounded in the service of their country, but so many men were beyond his help. He had to watch, helplessly, as men and boys—most he had known all his life—died in agony.

* * *

In July 1863 the tide of the war turned in favor of the North. The battle of Gettysburg was the victory for which Lincoln had so long waited and prayed. The president was not the only one glad to hear the news. The people of Puritan Falls saw Lee's defeat as a good portent.

For Hannah Lansford, however, that summer bought only more heartbreak. This time it was her young son who died. The grieving mother was so distraught by the loss of her child that it was nearly a month before she relayed the sad news to her husband and more than six months before she could move the coffin appliqué bearing Ethan's name from the border of her quilt to the cemetery in the center.

During Hannah's sorrowful ordeal, it was Phoebe Reynolds who helped her through each painful day. Phoebe empathized with the young mother, since she had lost three children all under the age of five before giving birth to Matthew, her only surviving child.

"I don't know how much more I can take," Hannah sobbed as the older woman cradled her in a maternal embrace. "I lost my parents, my father-in-law, my aunt and now ...."

The remainder of her sentence was lost in a renewed bout of tears.

"I know it's hard. I've been through it myself, but you will survive. You have to. And once Henry comes home from the war, you can have other children."

It was only the memory of happier times with her beloved husband that gave Hannah Lansford the will to get out of bed each morning and perform the mundane chores necessary to sustain life. Thanks to Henry's love-filled letters and her close friendship with Phoebe Reynolds, Hannah slowly came back to the world of the living.

In June of 1864 the two women's roles would be reversed. On the day spring officially gave way to summer, Phoebe received word that Matthew had been killed at the battle of Cold Harbor, and it was Hannah who gave her friend the courage to go on.

"Death isn't the end," the young woman reasoned. "We will all be reunited with our loved ones when we are called to heaven. Why, right now, Matthew is probably getting to know the brothers and sister he didn't meet in this world."

"Hannah, would you do me a favor?" the grieving woman asked after the funeral ceremony held at the Puritan Falls Church. "Will you put a coffin for Matthew on your cemetery quilt?"

"I'd be honored."

Thus, young Matthew Reynolds took his place among Hannah's parents, Henry Lansford, Sr., Aunt Viola and little Ethan. Hannah's tears wet the dark fabric of the quilt as she saw the growing number of coffins placed in the center squares. Only two coffin appliqués remained on the border. The two names embroidered on them were hers and Henry's. Which of them would be next?

"Oh, God," Hannah cried. "Let it be me. I couldn't bear losing my husband!"

* * *

In spring of 1865 the North rejoiced at the fall of Richmond. Even better news soon followed: on April 7, 1865, Robert E. Lee surrendered to Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House.

Now Hannah's tears were ones of joy.

"Henry will be coming home at last!"

While Phoebe was glad for her friends and her country, she felt the pang of sadness that her son would not be among the returning heroes.

After the local troops mustered out, the people of Puritan Falls gathered at the train station to welcome them home. Phoebe was waiting in the Lansford parlor for Hannah to finish dressing.

"You best hurry, dear," Mrs. Reynolds advised. "The train is due to arrive any minute now."

"I'll be right there," Hannah replied. "I want to look my best for Henry."

She took one final peek in the mirror.

"I'm ready," she gaily announced.

As she turned toward the bedroom doorway, her eyes caught a glimpse of the mourning quilt hanging on the wall.

Something's not quite right, she thought as she crossed the floor to get a better look.

Hannah's piercing scream brought Phoebe into the bedroom at a run.

"What's wrong?" she cried.

Her eyes followed Hannah's gaze to the quilt.

"Why did you put Henry's coffin in the cemetery?"

"I ... I didn't. I don't know how it got there."

Phoebe examined the quilt more closely. "The date of death is three days ago. That's ...."

Hannah didn't wait for her friend to finish. Without putting on her bonnet, she ran out of the house and headed toward the train station. She beat the locomotive to the platform by only a few moments.

Where are you? she thought with desperation as she searched the haggard faces of the men returning from war, looking for her husband's handsome features among them.

"He's not here!" she moaned to Phoebe, who had finally caught up to her friend.

"The train was full. He'll probably be on the next one."

As Hannah stood on the platform, watching the many tearful reunions around her, she heard the door of a freight car slide open. She turned at the sound and saw two Union soldiers unload a coffin. She did not need them to tell her it belonged to her husband.

* * *

"The poor thing!" Phoebe Reynolds exclaimed as she looked down at the body of her friend, which had been brought back to the Lansford home on Danvers Street after Hannah collapsed at the train station.

"She must have died of a broken heart," the village's elderly minister surmised after learning of the deaths of both Dr. Lansford and his wife.

Phoebe nodded her head in agreement.

"It was quite a shock to her. She had expected Henry to come back alive."

"That was a real shame," said the soldier who had helped carry Hannah's body to the house, "the doc dying like that after the war was already over."

"Is there a blanket we can put over her?" the minister asked. "At least until the doctor from Copperwell arrives."

"I'll get one," Phoebe volunteered.

She walked into the Lansfords' bedroom and took the cemetery quilt down from the wall. When she placed it over Hannah's lifeless form, she noticed that the dead woman's coffin appliqué had been moved from the border to a spot beside her husband and son in the center portion of the quilt.

Unlike Hannah, Phoebe did not scream with horror at the sight of the supernatural at work. Rather, she saw it as a sign from God that Hannah and Henry Lansford were reunited at last.

No doubt, at this very moment, the two are embracing little Ethan and each other, she thought.

A tearful Mrs. Reynolds smiled down at the dead body lying on the sofa, taking comfort in the knowledge that she would see her beloved son, Matthew, again someday.

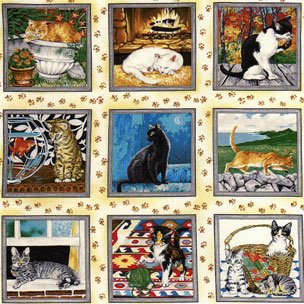

The image in the upper left corner is of the center of an actual mourning quilt. This story was inspired by an article I read in History magazine about mourning quilts.

Look what's in the center of my quilt! (Bet you didn't expect that.)