Comic Situation

Terry Mulligan was born in the year 1938. When the boy took his first breath, no one noticed the particular significance of the year. FDR was at the helm of the country, navigating America through the rocky waters of the Great Depression, and German troops entered Austria. It was the year that gave us the federally mandated minimum wage, the first Seeing Eye dogs, Walt Disney's first full-length animated motion picture, Seabiscuit's victory over War Admiral, Orson Welles's War of the Worlds broadcast and the March of Dimes polio foundation. As far as Terry Mulligan was concerned, what was later to prove to be the most significant event of 1938—other than his own birth—was the appearance of the first Superman comic.

Terry's earliest memories as a child, however, involved baseball, not superheroes. His father, although a New Englander, was a die-hard Yankee fan. Once a year, he took his wife and young son to the Bronx to watch a game at Yankee Stadium. The only other games the Mulligans attended were Yankees-Red Sox matches at Fenway Park.

When Terry turned five, he began playing Little League baseball. Although he was a fairly good hitter, with a batting average around .270, pitching was his forte. He set a team record for strike-outs and consistently had the lowest earned run average in his age division. Everyone in Puritan Falls naturally assumed he would play professional baseball when he grew up, so it was no surprise when a major league scout came calling.

"He'll be here any minute," Mabel Mulligan announced, nervously looking around the living room to make sure nothing was out of place.

"Relax, Mom. He's a baseball scout, not a representative of Good Housekeeping."

In Terry's mind, the meeting was just a formality. He already saw himself pitching for the Yankees and even envisioned his plaque in Cooperstown among such luminaries as Babe Ruth, Honus Wagner and Ty Cobb. Failure was simply not an option for him.

"He's here!" Mabel called excitedly.

"Why don't we go upstairs and let Terry talk to the scout privately?" her husband, Gilbert, suggested.

"But he's only a boy," she objected. "He knows nothing about business matters."

"If he wants my advice, he'll ask for it. He's going to be eighteen. It's high time we start treating him like a man."

Terry answered the door, invited the scout inside and offered him a cup of coffee.

"No, thanks, kid," the former minor leaguer-turned-scout replied. "I won't be staying long. I've got a train to catch."

"Let's get to it, then," the teenager said, feeling even more confident because of his father's belief in him. "Do you have any papers for me to sign? Or do my parents have to be here because I'm technically still a minor?"

The scout temporarily lowered his eyes and shook his head dolefully.

"Look, kid, I'm not gonna give you the soft treatment. I think you're old enough and mature enough to hear the truth. You've got a good arm—I'll give you that. But there's no place for you in the Red Sox organization. Your fastball is good. It might even get you a spot on our double-A farm team. Your curveball is good, too. Not great, but good. Your change-up—well, it needs a lot of work."

"I can improve," Terry protested. "Isn't that what the farm system is all about, developing young players?"

"Face facts, son. You were an ace in Little League, and you're an All-Star on your local team, but the majors? Do you honestly think you have what it takes to pitch to men like Mickey Mantle, Al Kaline and Vic Power?"

Terry's self-confidence was fading fast, but it wasn't completely gone yet.

"I might," he replied softly.

"Maybe another scout will feel differently; maybe you can play on a team like the Washington Senators."

"A last place team?"

"You want my advice, kid? Get a steady, nine-to-five job and forget about being a pitcher. You'll be happier in the long run; believe me."

Just moments after the front door closed behind the Boston scout, Mabel Mulligan came into the room, followed closely by her husband.

"How much did he offer you to play for the Red Sox?" she asked excitedly.

"Nothing. He said I'm not good enough for the team."

"My son not good enough?" Gilbert cried with outraged pride. "Who does he think he is? Last year Boston finished in fourth place, eighteen games behind the Yankees."

"There are other teams," the boy's mother said hopefully.

"Yeah, there are," Terry replied, "but I don't want to spend my life on a last place team. If I can't be a winner, then I don't want to play."

"What will you do with your life, then?" the father asked.

"I don't know yet, Dad, but I'm sure I'll find something."

With his dreams of being a professional baseball player behind him, Terry Mulligan went to his room, stretched out across his bed, reached for a comic book on his night table and escaped his problems by reading Clark Kent's latest adventure.

* * *

Thankfully, throwing a baseball wasn't Terry's only skill. As a child, he'd also had a knack for drawing, although it was a talent he never took seriously. It was high time he did, he decided.

After graduating from Puritan Falls High, he attended art school and got a job working for Action-Pack Comics. It was nothing as glamorous as drawing his own comic books, but he had ambition. For five years, he regularly brought ideas for a superhero to his employer, Quincy Gladwin. Each time, the publisher rejected Terry's work.

"Look kid," Quincy told him after examining the young artist's latest comic strip entitled Mega Man, "you're a talented artist. There's no doubt about that, but your ideas ...."

Oh, no, here comes another "look-kid" rejection.

The aspiring comic book artist frowned with disappointment and gathered up his artwork. Maybe he ought to think about a new profession—but the publisher was not finished speaking.

"... are all based on existing characters. I'm not looking for another version of Superman, Batman, Captain Marvel or Spider-Man. If you can come up with something new and fresh, something no one's seen before, I'll consider publishing it."

Terry's spirits instantly rose. Here was his big chance for his own comic. For months he racked his brain trying to think of an innovative idea, but time and again the creative spark escaped him.

"No luck yet?" Gilbert asked his son when Terry stopped by his parents' house late one Friday morning in July during his two-week vacation.

"There are so many different superheroes out there already: the Human Torch, Aquaman, Electro the Robot, Hurricane, Jack Frost ...."

"There's really a superhero named Jack Frost?"

"Yeah. Honestly, Dad, I can't think of an original superhero, no matter how hard I try."

Gilbert looked at his son's hangdog expression and took pity on him.

"Why don't you just forget about your job for today?"

"I can't. This isn't just a job; it's a career."

"You have your whole life to worry about your career. For this one afternoon, you can forget about comic books. The Red Sox are playing the Yankees, and you and I are going to go to Fenway and enjoy a game, just like we used to."

"You got tickets? I thought the game was sold out."

"I have a friend with connections."

The smile on Terry's face was worth every penny Gilbert had paid the scalper for the tickets.

In the capacity crowd at Fenway Park, there were many fans who had driven up from New York to see the game. Not only was there the usual attraction of the rival teams squaring off, but it was also 1961: the year Mickey Mantle and Roger Maris battled each other to beat Babe Ruth's single-season homerun record.

"There's a full house here today," Terry said as he and his father tried to make their way through the crowds to their seats on the first base side of the field.

"The Yankees pull them in wherever they play," Gilbert said with fierce pride in his team. "Ever since they got Babe Ruth, they've been the team to beat."

"Want a couple of hot dogs?" Terry offered after they sat down.

"What's a baseball game without a hot dog?" his father replied with a laugh.

While father and son were enjoying their frankfurters, a couple from Connecticut sat down in front of them. Accompanying the man and wife were their two sons, ages ten and twelve.

"They remind me of you when you were their age," Gilbert said, taking notice of the baseball caps and Little League gloves the boys had brought with them. "You always wanted to catch a foul when you came to the ballpark."

Terry looked at the two boys and noticed they were arguing.

"Nobody's better than Mantle," the older of the two insisted.

"Nobody but Maris," the younger countered.

"If anyone's gonna beat the Babe's record, it'll be Mickey."

"Think again. Roger can run circles around Mantle."

"Oh, yeah? Then how come Mantle's got thirty-six home runs and Maris has got only thirty-five."

"That's just a one-run difference, dummy, and it's only July. By the end of the season, I'll bet Maris is ahead."

"Boys!" the mother warned crossly. "We didn't drive all the way up here so that you two could argue."

By the time Terry washed his hot dogs down with a Coke, the Red Sox had taken the field. Bill Monbouquette was on the mound. Bobby Richardson and Tony Kubek were already out when Roger Maris stepped up to the plate.

"Come on, Rog. You can do it," the younger boy from Connecticut urged.

The child's faith was rewarded. Maris hit a line drive deep into right field for his thirty-sixth home run of the season.

"What did I tell you?" the boy goaded his older brother.

"The season's not over yet," the older boy countered. "Mickey will hit more home runs. You wait and see."

The boys didn't have to wait long. Mantle stepped up to the plate after Maris scored and hit a long drive deep into center field.

"That's why Mickey Mantle is my hero!" the older boy said after giving the Yankees' centerfielder a standing ovation. "I'll bet he could even outplay Superman!"

Terry didn't notice that Yogi Berra followed Mantle in the lineup. In fact, he didn't pay much attention to the remaining eight and a third innings. Thanks to the two boys from Connecticut, he had come up with an idea for a new superhero. Thus on July 21, 1961, Terry's head was as filled with ideas as Fenway was with baseball fans.

* * *

Early Monday morning, before most of the employees checked in for the day, Terry Mulligan was in his boss's office pitching his idea.

"The Arm?" Gladwin asked, reading the title above the comic strip panels.

"Yeah. Casey 'the Arm' Rawlins is one of the best pitchers in baseball history. He's injured in a freak accident and dies. A medical research scientist rushes to Casey's aid, performs experimental surgery and brings him back to life. The surgery has unexpected side effects. Casey has superhuman powers: he can run, jump, and throw harder and faster than a normal human being."

"Which gives him an unfair advantage over the opposing team?"

"No. After Casey died, the reporters immediately broadcast the news of his death. The doctor can't risk anyone learning of his illegal operation, so the pitcher agrees to give up his identity and career and become a crime-fighter. The only problem is he can't contact his family and friends. He must live in anonymity."

"A baseball player turned superhero? It's original; I'll give you that! It's a good idea, kid, but ...."

Terry didn't know which word he hated worse: kid or but. In his experience, neither one ever preceded good news.

"... ever since Dick Grayson became Bruce Wayne's ward and his crime-fighting partner, Robin, kids want their superheroes to have sidekicks. Can you come up with a sidekick for the Arm?"

The artist thought a moment and recalled his recent trip to Fenway and the two little boys from Connecticut.

"How about a former batboy and fan? He could be the only person besides the doctor who knows the Arm's real identity. Maybe he could be a young orphan who idolizes the pitcher."

Quincy lit a cigar and sat back in his chair, blowing the smoke rings toward the ceiling as he made his decision. Terry, his heart beating wildly in his chest, awaited the verdict.

"Tell you what, kid ...."

There was that word again!

"... you give me three or four stories in comic book format, and I'll put it out in a limited run."

Terry felt like Don Larson must have felt when he pitched a perfect game in the 1956 World Series.

The first issue of The Arm of the Law appeared on comic book stands just days after the 1961 baseball season ended. Roger Maris had hit number 61, breaking the Babe's record, and Mickey Mantle had finished the season with 54 home runs. It proved to be another banner year for the Yankees, who ended the season with a record of 109 wins and 53 losses and went on to defeat the Cincinnati Reds in the World Series.

Due partly to the popularity of players such as Mantle, Maris, Berra, Ford, Kofax, Mays and Drysdale, Terry's new comic book was an overnight sensation. Casey Rawlins joined the ranks of Clark Kent, Bruce Wayne and Peter Parker as one of America's most beloved superheroes. Boys and girls alike envied Jamie Skeritt, the former batboy turned faithful crime-fighting sidekick, who remained at Casey's side from the first issue of the magazine.

* * *

As Terry Mulligan walked into the swank New York restaurant, he checked his reflection in the mirror. He was pleased with what he saw. Not yet thirty, he was in his prime: handsome and well-built—not to mention a very wealthy man.

"Ah, there you are!" Quincy Gladwin exclaimed when the graphic artist was led to the reserved table.

"Sorry if I'm late. The traffic in Manhattan was horrendous."

"You're not late," his publisher said. "In fact, you're ten minutes early."

"We're all early," noted the third person at the table. "That must be a good sign. Hi, I'm Connie Nagel."

Terry shook the proffered hand, and said, "Glad to meet you."

He thought both the handshake and the words were grossly inadequate. Given the exquisite beauty of the woman, he felt he ought to fall down on his knee and kiss her hand, or, failing that, recite one of Shakespeare's sonnets.

During the usual polite chitchat, the waiter came to take their order. No sooner did he collect the menus and step away from the table than Connie became all business.

"Warner Brothers wants to make a full-length animated cartoon based on the Arm, and they will pay you handsomely for the rights."

Connie had been prepared to negotiate with the artist, expecting the usual I-go-higher-you-go-lower routine. She was stunned when he accepted the first figure she quoted.

"That was easy," she said with surprise when the contract was signed before the salad was brought to the table. "I expected you to ask for more money."

The artist laughed, as though enjoying a private joke.

"What's so funny?" Connie asked.

"I didn't think about the money. I never do."

"Were you born into a wealthy family?"

"No. My Dad drives a school bus for a living."

"And you're not interested in money? You must be a devout comic book enthusiast."

"Honestly, all I ever wanted to do when I was a kid was play baseball. For years I dreamed of pitching for the Yankees, but then a scout from the Red Sox told me I'd never make it big in the majors. All I could hope for was a spot on the roster of a losing team. I decided then and there I wasn't going to settle for mediocrity."

"Well, you certainly haven't," Quincy said, proud of the accomplishments of his artist. "You've done remarkably well."

"I couldn't have done it without you," Terry admitted. "You gave me a chance, and I'll always be grateful."

Connie admired both the young man's honesty and his loyalty. In fact, there was not one thing she didn't like about him.

Ultimately, Warner Brothers made not one but four animated cartoons featuring Casey Rawlins and Jamie Skeritt, each one grossing more than its predecessor. The popularity of the movies further increased the sales of the comic books. Terry Mulligan became richer than he ever dreamed possible.

Money aside, he had the admiration of American youth and the respect of his peers. And unlike professional athletes who could remain on top for roughly twenty years—if they were lucky—his career could span decades. What was most important to him, however, were the people he had met and the relationships he had cemented. Quincy Gladwin had become like a second father to him, and Connie Nagel—well, she became the most important person in his life.

Unfortunately, the mood of the country in 1969 was drastically different from that in 1961. During the turbulent intermittent years a president had been assassinated, the Vietnam War escalated and antiwar protests, the demand for Civil Rights and the women's movement polarized the nation. In the psychedelic era of drugs, sex and rock and roll, Casey Rawlins and Jamie Skeritt were becoming passé. Baseball itself had been replaced by football as the most popular sport in America.

Terry was appalled when he saw the drop in sales of his latest issue.

"I don't understand it," he complained to Connie. "The figures continue to fall."

"Maybe it's time to make some changes," his fiancée suggested. "Maybe you should consider making the comic more relevant to today's youth."

"Should Casey have long hair and a beard, smoke pot and march on Washington?" he asked facetiously.

"Nothing so drastic."

"What then?"

"Well, try not to stick too close to the All-American boy image. This is the Sixties, after all, not the Forties or Fifties."

"He's a baseball hero turned crime-fighter. How can I avoid the All-American image without making him a bad guy?"

"You can give him a new sidekick."

Terry was floored by the suggestion.

"Replace Jamie Skeritt? But he's as much a part of Casey as his superhuman arm!"

"He's getting boring," Connie declared, hoping he would take her comments as constructive criticism rather than insults. "The idea of the adorable little boy went out with Timmy and Lassie."

Terry remembered the day at Fenway Park when he sat behind the two boys from Connecticut. They had given him the idea for the Arm and had been the inspiration for Jamie Skeritt. That was eight years ago. They were no longer children. He wondered what they were doing now. Were they in college? Were they fighting in Vietnam or were they peace-loving hippies? One or both of them might even be dead.

"Who could I replace him with?" Terry asked, reluctantly agreeing that it might be time for Jamie Skeritt to go.

"A woman—an intelligent, capable, liberated woman."

"Like you?"

"I was thinking more along the lines of Gloria Steinem," Connie laughed, "but I'll do."

"Any other suggestions?"

"Yeah, while you're at it, use a little more ethnic diversity, and I don't mean for the villains. The governor, the mayor, the police commissioner, the chief and everyone on the police force are all white men. Diversity is nothing new. The Lone Ranger has Tonto, the Green Lantern has Kato ...."

"I get it," he said. "Now all I have to do is find a way to get rid of Jamie Skeritt and introduce my new characters to my readers."

* * *

"I love it!" Connie cried when she read the latest issue of The Arm of the Law. "With these new characters, the comic is even better than before."

Quincy Gladwin agreed, as did Terry's readers. Soon, the sales figures picked up again.

"My career is saved!"

Not only did his existing fans approve of the female sidekick, the new African-American mayor, the Japanese detective, the Mexican news reporter and the Native American medical examiner, but the diversified characters appealed to a broader range of readers. Parents and child psychologists, who berated comic books as a form of entertainment, saw value in the Arm's diverse cultural message. Casey's partner in crime-fighting, Dr. Caterina Van Sise, an MIT-trained scientist, was an inspiration to a modern generation of girls who wanted to be more than secretaries, nurses, schoolteachers and housewives. Not only that, but her superior intellect effectively complemented Casey's superhuman strength.

Taking suggestions from Connie—now his wife—Terry began to create more sophisticated plots for his new characters, incorporating sensitive topics such as drug abuse, the war and the environment. While these changes appealed to a more mature audience, they did not repel the younger readers, who accounted for the majority of his sales.

"I really ought to include your name as co-author," Terry told his wife as he was preparing to send another issue off to his publisher. "After all, Caterina Van Sise was your idea. So were the other changes."

"I'm honored, really, but the work is yours. I wouldn't dream of taking any credit for it."

"Nonsense. I'd still be writing about Casey and Jamie and their all-white supporting cast if it weren't for you—that's if I still had enough readers left to warrant publishing any more issues."

"You're a talented writer and a gifted artist. You just needed a little direction: someone to tell you that the times they are a-changin'."

Terry wasn't the only one who believed Connie was responsible for revamping the Arm comics. Jamie Skeritt, the faithful batboy who for eight years fought villains at Casey Rawlins' side, put the blame for his death squarely on her shoulders. If it hadn't been for her suggestion that the Arm have a liberated female as a sidekick, Terry Mulligan would not have had Jamie Skeritt killed off by the Torpedo, the most devious of the Arm's enemies.

"Unlike her love-blinded husband," the unseen Jamie Skeritt decided while the human couple continued their discussion, unaware of his existence, "I'll give credit where credit is due."

* * *

Two days later, Terry was awakened by the persistent ringing of his telephone. His eyes still closed, he reached his arm across the pillow and picked up the receiver.

"Hello," he mumbled.

"What are you up to?"

There was no need for the caller to identify himself. Terry recognized the voice; it belonged to Quincy Gladwin, his publisher and friend.

"I was sleeping. Why?"

"I'm not talking about what you're doing now. I want to know what you're doing with the Arm. Why did you bring Jamie Skeritt back from the dead?"

"What the hell are you talking about?" Terry cried. "I haven't even mentioned Jamie Skeritt's name since Dr. Van Sise helped Casey solve his murder."

"I'm looking at your latest submission, and Jamie Skeritt is back. If you didn't draw these comics, then who did?"

"I don't know, but don't do a thing with them until I get there."

Terry threw on a pair of jeans and a T-shirt, grabbed his car keys and headed for the door. In twenty minutes—a record time—he entered Quincy's office.

As the publisher's assistant went to the break room to get the two men coffee, Terry studied the comic strips on the light table.

"This looks like my artwork; even the printing is identical to mine. But this isn't my story line. Did you keep the envelope these were mailed in?"

"I got it right here."

Terry's hand trembled when he looked at the front of the envelope.

"That's my handwriting, and the return address is mine as well."

"Are you sure you didn't send these drawings to me? Maybe they were old pages you grabbed by mistake and stuck in the envelope."

"They're not old sheets. One of the characters referred to Dr. Takahasi, who was introduced after Jamie Skeritt was killed off."

"If you didn't draw those comics, then someone must have tampered with the mail, replacing your work with these sheets. It's the only logical explanation."

"Maybe this has nothing to do with logic," Terry said, staring down at the drawings that were so like his own, that he had difficulty believing someone else had done them.

"Do you think we should call in the police?" Quincy asked.

"Why?"

"Someone stole your work and substituted his or her own. That seems criminal to me. Perhaps the police can get fingerprints off the envelope or the drawings."

When Quincy picked up the envelope, a sheet of paper fell to the floor.

"Another page?" the artist asked.

"That's impossible. I opened the envelope myself and put the pages there on my desk."

"You had to have left one inside the envelope.

"I've been a publisher for over 30 years. I didn't get to where I am today by leaving pages inside envelopes. I tell you I got them all out."

Terry sat down at Quincy's desk and carefully examined the sheet of paper.

"What's this?" he asked.

The publisher looked at the cartoon on the last page.

"I don't know. I don't remember seeing that sheet."

"It shows Jamie Skeritt killing Dr. Van Sise. What kind of sick mind would come up with this shit?"

Quincy Gladwin stared at the artist uneasily.

"Are you sure you didn't draw these? You said yourself it was your handwriting."

"Do you think I'm losing my mind? Drawing pages without remembering them? And why would I kill off the ...?"

Terry dropped the piece of paper as though it had burned his hand.

"What's wrong?" Quincy asked anxiously.

"The comic ... it changed right before my eyes!"

The sheet of paper now contained a single cell, a close-up drawing of Jamie Skeritt, the former batboy turned crime-fighting sidekick, with a dialog bubble above his head.

"What's it say?" the publisher asked.

"It says I deserve what I got, that I never should have replaced him."

"What does all this mean?"

"I don't have a clue," Terry replied, gathering the pages into a pile.

"What are you gonna do with them?"

"Get rid of them. Burn them, if necessary."

The pages scattered as though a strong wind had blown through the room. The close-up of Jamie Skeritt landed on the publisher's desk.

"You better take a look at this," Quincy said, his eyes wide with horror.

"What is it now? I don't ...."

The message in the dialog bubble was short and clear:

You should have listened to me. If you had, your wife might still be alive.

* * *

"This can't be happening," Terry cried. "It must all be some horrid nightmare!"

"It's God's will," his mother declared, hoping to comfort her grieving son.

"She was so young," his father said, looking down at Connie's body, lying peacefully in her coffin. "Who would have suspected she had such a serious heart condition?"

"At least she didn't suffer," his wife added.

But she had suffered. Terry was sure of it. He could clearly remember the look of terror on her face when he and Quincy discovered the body. She had literally been scared to death.

After the funeral services were concluded, Terry went to his mother's house where a buffet lunch was set up. Family members, neighbors and friends offered the widower their condolences as they filled plates with sandwiches and salads.

Finally, around four in the afternoon, the last of the guests departed, and Terry was alone with his parents.

"Why don't you stay here tonight?" Mabel offered. "You can sleep in your old room."

"Thanks, but no. I have some work that needs to be done, and I can't put it off any longer."

"I'm sure Mr. Gladwin will understand; after all, you just lost ...."

Her husband put his arm out to silence her.

"Let him go. Maybe work is what he needs now."

Waiting only long enough for his mother to fill Tupperware containers with leftovers for him to take home, Terry left his boyhood home and returned to the house he had shared with his wife. Tears rolled down his cheeks as he crossed the threshold. He had carried Connie over it when they returned from their honeymoon. More recently, he had seen her corpse leave through the same doorway on a gurney.

After dropping the sandwiches and salads on the kitchen counter, he walked resolutely to his den. He sat at his drawing table, grabbed a sheet of paper and a pencil and began sketching Jamie Skeritt's head.

"Now, let's see what you have to say for yourself, you little bastard," he swore after drawing a dialog bubble above the boy's features.

He waited. Nothing happened. Frustrated, he crumpled the paper into a ball and threw it in the wastebasket.

"What's wrong with me? Did I really expect a comic book character would confess to killing my wife?"

Suddenly the top page on the stack of papers was no longer blank. The face of Jamie Skeritt, smiling malevolently, looked back at him.

"What do you want?" the artist asked.

Words immediately appeared in the bubble.

She had it coming. Casey and I made a good team until your wife put her nose into things.

"So you did kill Connie?"

Yes, but I acted in self-defense. Besides, she had me killed off.

"That was my idea, not hers."

She wanted Casey to have a woman sidekick and convinced you that I didn't matter to the fans.

"You didn't. The Arm is more popular now without you than it ever was with you."

I don't care about comic book sales. I had a life! I was someone special.

"No, you weren't. It was all about Casey Rawlins. He was the former baseball star. He was the one with the superhuman strength. You were just a batboy."

You make it sound like I was a sissy. I wasn't no boy scout. You forget that I was born and raised in the Bronx.

"You think you're streetwise because you're from New York."

Damned right. I had enough smarts to outwit you, didn't I?

Terry's anger flared and he had the sudden desire to spill a bottle of ink over Jamie's repulsive little face.

"I won't bring you back. You're going to stay dead, and if there's a hell in your comic book world, I hope you rot in it."

Don't be so hasty, Terry. If you hadn't already noticed, I can kill with impunity. I don't have to stop with your wife.

"If you want to kill me, go right ahead. I don't give a damn anymore."

Kill you? I wouldn't dream of it. I need you to give me back my life. But your publisher? Who'd miss him? You're a big name now. You can go over to Marvel or DC Comics. And then there are your parents. I'll take away every person you care about, one by one, until you do as I say.

Terry threw his head back and stared at the ceiling. He was defeated, and he knew it.

"I suppose I don't have any choice. Okay, you win. I'll ...."

When the artist looked down at his drawing table, he saw that the page was blank.

"What happened? Where did you go?"

Within moments, the white paper came alive with color. Casey "the Arm" Rawlins and Dr. Van Sise were standing above the body of little Jamie Skeritt.

"I know how much you cared about him, but you did the right thing," the MIT-educated scientist remarked in her dialog bubble. "You had no choice but to kill him. It was either him or me."

The crime-fighting former pitcher turned away from the scene. A close-up of his face revealed tears in his eyes.

"He was like a kid brother to me."

Caterina put her hand on Casey's extraordinarily strong arm in a gesture of friendship and support.

"With Jamie gone, you and I can continue to fight crime and try to make the world a safer place."

When the ink faded, leaving behind a pristine sheet of white paper, Terry Mulligan instinctively knew he no longer had to fear for his loved ones' safety. The character he had patterned after two little boys from Connecticut had been destroyed for good. Dr. Caterina Van Sise would continue to fight crime at Casey's side.

The fact that he still had a successful career ahead of him brought Terry some comfort as he faced the future without Connie.

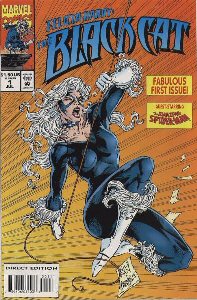

Image in upper left corner is from the cover of COTTON WOODS: The Comic Strip Adventurues of a Baseball Natural by Ray Gotto, published by Kitchen Sink Pr (1991). Image below is of the cover of FELICIA HARDY: THE BLACK CAT, Edition #1, published in 1994 by Marvel Comics.

Salem's favorite superhero is a woman: Felicia Hardy, the Black Cat. (What else?)