Weird Sisters

Through hard work and perseverance, Errol Kilbourne, a poor young man from Ireland, graduated from St. John's College, Cambridge, in 1818 and became an Anglican priest. Upon completion of his studies, the young curate was sent to St. Michael's Church near North Riding of Yorkshire to assist the aging vicar. During his tenure there, he fell in love with a local girl and married. After three daughters, his wife gave birth to a son, Terrence.

The year the boy turned four, two deaths would forever change Errol's life and have a lasting impact on his family. The first happened in March. The elderly vicar, whose health had been declining for some time, quietly passed away in his sleep. Upon his passing, the young curate was then appointed rector of St. Michael's. The second death, five months later, one far more devastating and unexpected, was that of his wife.

Rather than remarry, the widower chose to raise his four children on his own. A firm believer in education, he began teaching his son and daughters reading, writing and mathematics not long after they learned to speak. At an age when many children were learning the alphabet, the Kilbourne brood could read and write most of the two-syllable words in their primers.

"When you are older, I'll teach you science, philosophy, history and geography," Errol promised the youngsters.

"Why do we have to learn so much?" asked his son, who was not the eager student his sisters were.

"You need to prepare yourself for adulthood. With proper education, you can go to Cambridge, like I did, and become a vicar. Your sisters, should they not marry, can provide for themselves by becoming teachers or governesses."

"Not me," insisted Rachel, the oldest of the girls. "I'm going to become a writer someday."

"Girls can't write books," argued Terrence, who, although the youngest, believed he was the wisest of the siblings based solely on his masculine gender.

"If a woman can rule England, as Elizabeth once did, then a woman can write a book."

Errol smiled wanly at his daughter's aspirations. Although he did not want to discourage her, he believed she was just as likely to sit on the throne herself as become a published author.

I suppose I have only myself to blame for the fanciful ideas of my children, he thought, particularly the girls. I'm the one who encourages them to read so much.

Reverend Kilbourne saw no harm in their storytelling, for the rather isolated parsonage in which they lived, surrounded by moorland, had few creature comforts, much less luxuries. There were no curtains on the windows or carpets on the floors. Except for the warmest days of summer, a chilly dampness pervaded the rooms, one not even a roaring fire could easily dispel. Furthermore, candles provided the only source of lighting, and they created gloomy shadows even during daylight hours.

Unsurprisingly, this oppressive atmosphere began to seep into his daughters' tales. The youngest girl, Dinah, was fascinated with Mary Shelley's Frankenstein and liked to imagine mad scientists reanimating all sorts of monsters. Beatrice, the precocious second-born child, loved to spin yarns about ghosts and restless spirits returning from the grave. Most likely because Rachel was the oldest, her fiction was more sophisticated. She was interested in diseases, especially of the mind. Her stories dealt with untimely death, insanity, suicide and murder.

Many a time, late at night, after their father had gone to bed, the girls would share their chilling fictional creations by candlelight. Terrence would often sneak out of his room and listen to them from the hallway, even though their tales often gave him nightmares afterward. The girls, of course, were aware of his eavesdropping and delighted in frightening their young sibling, as older children often do. They were not motivated by malice—they loved their brother—but only sought to have some harmless fun at his expense.

"You needn't be such a scaredy cat," Rachel once told him in a moment of sisterly affection. "Our stories aren't real. They're just make-believe. There are no such things as ghosts or reanimated dead bodies."

"I'm not afraid!" Terrence declared defiantly; he was a boy, after all, and believed it was unmanly to show fear. "And I think your stories are stupid! All of them. Not one of you is any good at storytelling. Furthermore, you remind me of the witches in Macbeth, the Weird Sisters."

Beatrice, who took great pride in her literary efforts, was offended by her brother's insults.

"Odd that you should mention witches," she said, smiling mischievously. "Because it's not ghosts you have to be afraid of, dear brother. It's Mary Bateman, the Yorkshire Witch."

She then proceeded to tell Terrence about the woman born in nearby North Riding in 1768. The servant girl-turned-seamstress embarked upon a life of crime that included burglary, begging under false pretenses and bribery of prison officials. The enterprising young woman then reinvented herself as a fortuneteller and wise woman and often used elaborate hoaxes to dupe her unsuspecting customers.

"Then something went wrong with one of her so-called spells," Beatrice said, dramatically building suspense as she recounted the true story of Bateman's downfall. "A woman named Rebecca Perigo died from the poison Mary gave her. The witch was arrested for murder, and no amount of bribery was able to free her this time."

"What happened to her?" Terrence asked.

"She was hanged from a giant tree. Afterward, her body was cut down and taken to a nearby infirmary where the medical staff sold tickets to people who wanted to view the remains of the Yorkshire Witch. Then they dissected her. They tanned her hide and sold strips of her dried flesh as good-luck talismans to ward off evil. It's said her spirit still haunts North Riding in search of her missing skin."

"Don't tease him!" Rachel laughed, seeing the look of terror on the boy's face.

"It's not true, is it?" he cried. "She made it all up. Didn't she?"

"Not all of it," the oldest replied. "Most of what Beatrice told you about Mary Bateman is true, except for that part of her haunting North Riding. You see, although she was born there, once she married, she moved to Leeds. That was where she was hanged."

Terrence should have found comfort in knowing that the Yorkshire Witch was executed nearly fifty miles away, but he did not. He never forgot the harrowing tale of the skinned corpse coming back and looking for its flesh. Beatrice would not let him, for whenever he did something to anger her, she warned him to be on the lookout for Mary Bateman's ghost.

* * *

Since the age of seven, Terrence Kilbourne wanted to be a raconteur like his sisters, to create new and wondrous worlds with words, but he lacked their vivid imaginations and their gift for composition. If he thought of a good beginning for a story, he could not come up with a suitable ending. If a clever ending came to mind first, he did not know how to begin. And always there was the middle that gave him the most trouble, all those little details that carried a tale through to its conclusion.

After four frustrating years, during which he had completed only two of the hundreds of stories he started, he gave up all hope of writing fiction.

Maybe I have a talent for poetry, he thought, envisioning himself as the next Byron or Shelley.

It took him less than six months to realize how difficult even a short poem was to write. He could not combine rhyme and meter to form a simple verse, much less a sonnet or villanelle.

But there were other forms of artistic expression; he would try his hand at them all until he found one that he was good at. The church organist, as a favor to Reverend Kilbourne, began giving the boy music lessons. His attempts at the organ and violin were all atrocious, and he soon abandoned the idea of playing an instrument in favor of composing. He would sit for hours writing notes on staff paper, but when the organist played them, there was no discernible melody.

"I'm clearly no Beethoven or Mozart," he declared and, to his instructor's great relief, gave up all thoughts of playing or writing music.

As for singing, the boy not only lacked a pleasant-sounding voice, but he could not carry a simple tune.

"Singing lessons are clearly a waste of time," the choirmaster informed his father. "I'm afraid the lad is tone-deaf."

It was not until he held a brush and palette in his hand that Terrence found his true calling. His first painting was of the blooming heather on the moors.

"That's very good," Rachel said, complimenting his work and encouraging further efforts.

The other two girls agreed.

Next, he created a still life of a bowl of fruit beside a pitcher of water and a loaf of bread.

"You've got talent," his father pronounced. "You ought to try a religious subject in your next painting. All the great artists—Michelangelo, Caravaggio, Botticelli and da Vinci—painted for the Church. The Sistine Chapel is a masterpiece, and Raphael's Madonnas are exquisite! Perhaps you can ask one of your sisters to pose for you."

Beatrice as the Virgin Mary! Terrence thought with amusement. If I ever painted her, it would be as Mary Bateman, the Yorkshire Witch! Or, better yet, as one of Shakespeare's Weird Sisters.

Eventually, he would paint portraits of all three sisters and his father, none of which had a religious theme.

* * *

When Rachel turned seventeen, a time when other girls her age were getting married or having children, she began writing a novel. Her sisters soon followed suit. It was quite an undertaking, but they were more than up to it. Although the two older girls found work in North Riding—Rachel as a school teacher and Beatrice as a baker's assistant—they returned to the parsonage at the end of each day. Dinah, as the youngest girl, remained at home and was responsible for all the cleaning, cooking and laundry. The few hours the girls had to themselves they spent writing.

Meanwhile, when he was not busy studying theology and Latin, in preparation for a career as a vicar—his father's idea, not his—Terrence continued to paint. After completing the four family portraits, he painted one of the organist and his wife. His first paying customer was the village blacksmith, although he barely received enough money to cover the cost of the paints and canvas. But soon word of his talent spread and wealthier people came to him.

"I don't want to be an Anglican priest," he confessed to Rachel one evening after dinner. "I want to be an artist, a painter."

"Father has his heart set on your following in his footsteps."

"I know that, but this is my life, not his."

"There's no reason you can't be both. I'm a schoolteacher, and I still find time to pursue my writing."

"I don't want painting to become a mere hobby. I want to devote my life to it."

"You're still young. Wait a bit longer before you tell Father of your decision. By then, he may see that you can make a good living painting portraits."

Of course, there were things other than human faces that appealed to the artist in Terrence. Birds, flowers, trees, sheep, clouds: he saw something beautiful in all of them. One of his favorite subjects was St. Michael's churchyard. From the window in his room in the parsonage, he had an excellent view of crosses, headstones and statuary that marked the graves. In between portraits of his paying patrons, he painted the same scene several times, varying the time of day, the weather conditions and the season of the year.

"You're painting the graveyard again?" Beatrice asked when she saw him at his easel in front of the window.

"Yes. The leaves are just about done falling, and the ground is nearly covered with them. It's quite lovely."

"But you've painted it in the autumn before."

"With the sun shining brightly," he explained. "Now it looks as though a storm is coming. The sky is the color of slate."

"If I didn't know any better, I'd swear a spell was cast upon you," she teased. "Maybe Mary Bateman's ghost is wandering in our churchyard, compelling you to paint her."

"Save your scary tales for your novel, Beatrice. I'm not afraid of such things as ghosts and witches anymore."

"Too bad. It was fun to scare you when you were younger," she said and went to her room to write.

Three weeks later, before the cold weather set in and the ground began to freeze, there was a death in the village. That meant another grave would be dug in the churchyard.

"That will give you something new to paint," Beatrice whispered to her brother, so their father would not overhear.

"And maybe it will mean another restless spirit for the Weird Sisters to write about."

Death was never to be taken lightly as far as their father, the vicar, was concerned. It was especially true in this situation, for the deceased, a young wife and mother not yet thirty, had died of consumption, a deadly, contagious disease for which there was no known cure.

* * *

At the end of January, there was a severe, blizzard-like storm. Terrence sat at his window, painting the tops of tall headstones that were protruding out of the snow. The shorter ones were covered with white mounds. Beatrice no longer teased him about his churchyard scenes. He had become so obsessed with the growing number of graves that he barely left his room, and his sister rarely entered it.

"There's been another death," a saddened Errol announced to his children when he sat down at the table for dinner. "I don't know where we're going to put this one. The ground is frozen, and the receiving vault is full."

"They'll be a lot of new graves come spring," Terrence said, his blue eyes glistening with eager anticipation.

The vicar and his daughters turned their heads away. Although none of them spoke of it aloud, they all feared the youngest member of the Kilbourne clan was insane. There was no question of seeking psychiatric help for him. They would never allow him to be sent to an asylum where he would be forced to live under deplorable conditions.

I'll keep him at the parsonage, the forlorn father decided. He'll be content to stay in his room and paint all day. God willing, I'll live a long life and have the means to take care of him. And after I'm gone, his sisters will take over that responsibility.

Eventually, the uncomfortable silence was broken. Beatrice was the first to speak of her brother's madness.

"It's all my fault," she told her sisters as the three women sat in the parlor in the gathering gloom of a winter evening. "If I hadn't tormented him with taunts about the Yorkshire Witch, he might ...."

"Stop it!" Rachel cried. "His illness is not your doing. He was always nervous and high-strung, even as a little boy."

"It's this place," Dinah suggested. "It's so dreary and depressing. And if he looks out his window, what does he see? A graveyard!"

"But we were all raised in the parsonage," Beatrice pointed out. "We haven't been affected by the melancholy atmosphere."

"Haven't we?" Rachel asked. "We all want to be writers, but not one of us hopes to emulate Jane Austen. Let's face it. Terrence is right. The three of us are weird. Our novels all deal with chilling, macabre subject matters. Perhaps that is a form of madness, too."

As the vicar's family was coming to terms with Terrence's troubled mental state, consumption spread to others in the village. Historians would later conclude that one in seven people died of tuberculosis at the beginning of the nineteenth century. While North Riding did not see nearly as many cases as more crowded locales like London, it did not escape the growing epidemic. Whenever a villager, young or old, developed a chronic cough, chest pain, fatigue or fever, family members feared the worst. Consumption did not cause a quick death, like the plagues of the past. Patients often lingered for years, slowly wasting away. Soon nearly one-fourth of the people in the village were conducting a prolonged deathwatch for a friend or relative.

On the bright side—if there can ever be a bright in such tragic times—Terrence handled his confinement well. He seemed to not even realize that his family had become his warders.

"Father no longer speaks of my following in his footsteps," he told Rachel when she brought him his dinner on a tray. "He must realize sending me to Cambridge would be pointless. I was thinking I might go to Florence one day to hone my skills. That's where so many of the Renaissance painters worked."

"That would be nice," his sister said, holding back her tears.

"Or perhaps Rome. I would love to visit the Vatican and see the Sistine Chapel."

"Just don't convert to Catholicism while you're there. You know it would upset Father."

"Speaking of our parent, where is he?"

"There's been another death in the village."

"Good God! The churchyard will soon be overcrowded. St. Michael's will have to start burying people on the moors."

As she left her brother's room, her thoughts went to the grieving parents who had just lost their last remaining child after losing the other four to consumption.

They died so young, but at least they are all at peace now.

The same could not be said of her brother. In perfect physical health, he could, in all likelihood, live with his madness well into old age.

* * *

Another winter had come. The cold seemed to seep not only into the stone walls of the parsonage but also into the bones of those who dwelled inside. It was no wonder that everyone in the house, except for Terrence who rarely ventured outside the confines of his room, came down with a cold.

I hope I don't catch it from one of them, he thought as he tossed another log on the fire.

After warming his hands over the blaze, he went back to the window, picked up his brush and continued to paint. He rarely saw his sisters anymore. Since they had taken ill, they remained in their rooms and did not even go to their work in North Riding.

They're probably busy writing their novels. They always were weird, all three of them, but Beatrice most of all. She's a lot like that American fellow Poe she's always going on about.

Putting his siblings out of his mind, he turned his attention to the view outside his window. The sleet striking the roof provided a dramatic soundtrack to the eerie quiet of the churchyard. Trees that had only a month earlier been bathed in reds, golds and tans of autumn splendor now resembled bare sticks with only a few brown leaves clinging to them.

That's the way some people are, he mused. They desperately try to hold on to life, no matter what. I hope when my time comes that I can face it like a man.

But he was still young, and he saw death as being something on the distant horizon. Despite seeing ample evidence of the Grim Reaper's hand at work right outside his window and in his paintings, his own mortality remained an abstract concept. As he painted the headstones for the umpteenth time, he gave little thought to the bodies buried beneath them. True, many of the graves were of people who had died before he was born. They were names without faces. However, there had been more recent burials, including that of his own mother of whom he still cherished a dim memory. He was well aware that she was deceased, but he never imagined her bones, wrapped in a shroud, lying under the ground.

That was the difference between Terrence and his sisters. He saw the superficial attractiveness of the churchyard—the trees, the statues, the flowers, the carved headstones—whereas Rachel, Beatrice and Dinah were all too aware of the morbid truth those images represented. That they were not driven mad by living in close proximity to a graveyard was due, in no small part, to their writings. They did not harbor thoughts of death in their minds but, instead, let them pass through their hands and onto paper.

By mid-afternoon, the young man added the final details to his painting.

"That's it!" he announced to the empty room. "I've completed another one."

He removed the canvas from his easel and leaned it against the wall.

"Once the paint dries, I'll add it to my growing collection in the attic."

An idea suddenly came to him.

There's an overhead view of the churchyard from the window up there. I've never painted the graves from that angle.

However, it was too late in the day to begin another painting. The darkness of night was already creeping toward the parsonage. He would have to wait until morning.

* * *

The sun was shining brightly when Terrence woke, but the temperature was still only slightly above freezing. Since there was no fireplace in the attic, he put on several layers of clothing to keep warm. Then he collected his easel, palette, paints, brushes and a fresh canvas and climbed the narrow staircase.

It's so cold up here; I'm surprised I can't see my breath.

He walked to the window and organized his workspace. Then he found an old stool and positioned it in front of the easel. As he added paint to his palette, he glanced out the window. From that height and angle—there was a ninety-degree difference between this window and the one in his room—he had an excellent view of many of the graves that were added since the consumption epidemic invaded the village.

As was his custom, he chose a large brush and quickly painted the gray sky and frost-covered ground. Once he had created his horizon, he picked up a smaller brush and painted, over the course of several days, the stickman-like figures of the denuded trees. He was also able to see from the attic window, severa; evergreens and a small brook that was now frozen over. These he painted with greater care because they were new to him and represented uncharted territory.

Several times while painting, he stopped to warm his hands over the lit candle. Normally in cold weather, he was prone to shivering and chattering teeth. Thankfully, such was not the case since it was hard to hold a brush steady under those conditions.

In the early evenings, the darkness of the attic adversely affected his ability to distinguish the shades of color of his paints. Reluctantly, he was forced to put down his brush and return to his own room.

The following day, although the sun played hide-and-seek with snow clouds, the temperature was considerably warmer. Eager to resume work on his landscape, Terrence climbed the stairs to the attic, which he had dubbed his atelier. For several days, he had worked on the small details of the scene, starting on the right side of the canvas, painting the headstones and statuary he could see from his own window. He had painted them so many times, each detail was committed to his memory. Once the right side of the painting was completed, he spent the next week concentrating on the middle of the canvas. A blend of the familiar and unfamiliar, these graves took twice as long to paint.

By early afternoon, he added the last touches and was ready to fill in the remaining details on the unfinished portion of the canvas. However, as he added fresh paint to his palette and prepared to begin work on the left side, the storm clouds became the victor in their contest with the sun.

There might just be enough light left for me to paint a few of the graves near the evergreen trees, he thought optimistically.

As he dipped his brush into the oils on his palette, he realized with a shudder that the headstone he was painting belonged to his late mother.

It's been so long since I visited her grave that I almost forgot what it looked like. And what's that headstone near it? I don't remember that being there.

Terrence squinted, but at a distance, he could not read the name carved into it.

I don't suppose it matters much. There are so many people buried out there now that I can't keep up with them all.

Try as he might, though, he could not put the ominous tombstone out of his mind.

Maybe Beatrice is right. Maybe I have become obsessed with the churchyard.

"Oh, great! It's snowing," he said, his voice echoing through the cavernous attic. "I hope it doesn't continue through the night. If it does, it will cover the graves, and I won't be able to finish my painting until it melts away."

"And you won't be able to see the name written on the headstone."

"Who said that?" he cried, but he was alone in the room.

It could only be one of my weird sisters. But which one?

"Is that you, Beatrice? What are you doing up here? Can't you see I'm painting? Do I bother you when you're working on your novel?"

No one answered; no one was there.

I'm hearing voices. Could I be losing my mind? he wondered. Has this place finally gotten to me?

Terrence's eyes returned to his unfinished painting. Inexplicably, the unknown grave seemed to have doubled in size, to the point where it was dwarfing those around it.

"Whose grave is it?" he asked aloud.

His question was repeated by the identified voice, which now seemed to reverberate in his brain.

"Whose grave is it ... is it ... is it?"

He threw down his brush and palette and ran down the attic stairs.

"Whose grave is it ... is it ... is it?"

Hoping to escape the unknown voice that taunted him—could it be Mary Bateman, the Yorkshire Witch?—he ran out of the parsonage and toward the church. However, the door to St. Michael's was shut and locked.

"Father, where are you?"

"Whose grave is it ... is it ... is it?"

Terrence turned in the direction of the churchyard. His feet, as though acting with a will of their own, carried him past the headstones he had always seen from his window and toward his mother's grave near the evergreen trees.

"No!" he screamed in terror. "I don't want to know who is buried next to her."

But he was unable to make his feet stop. As he approached the mysterious tombstone, he could see there were multiple names engraved on it, but he was still too far away to read them clearly. He tried to turn his head away; when that attempt failed, he tried to close his eyes, which proved equally fruitless.

As was often the case when a family shared a headstone, the surname was engraved at the top in large letters. Thus, it was the first thing Terrence was able to read.

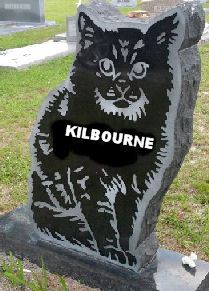

KILBOURNE.

"No. That must be a mistake. My mother is buried in the grave next to it. Her headstone is much smaller and older."

When his feet finally came to a stop, the young man could read all of the names below it. Errol. Rachel. Beatrice. Dinah. His father and his sisters had all died over a two-month period and were buried together.

They didn't catch colds, he realized. They had consumption.

But there was another name on the grave, one beneath Dinah's.

"No! This must be someone's idea of a cruel joke."

Terrence forced his head to turn away. He glimpsed an oak tree, bare except for a single brown leaf, shivering in the snow but still hanging on to the branch, like a drowning man clinging to a life raft. He was reminded of his own analogy comparing the stubborn autumn leaves to people refusing to let go of life. Despite his avowal that he would face death like a man, he now cowered before it.

"I'm not dead!" he screamed. "I'm not!"

His feet once again able to respond to his brain, he ran back to the parsonage and sought the sanctuary of his room.

* * *

"This is it," Max Rupert proudly announced as he turned off the car engine. "Our new home."

Fifteen-year-old Quinn put down her mobile phone and stared at what had once been St. Michael's parsonage.

"It looks like the House of Usher," she said.

"It's not that bad," Rosanna, her mother claimed. "Once I get to work my interior design magic, it will be quite homey."

"It ought to be," her husband laughed. "I spent a small fortune modernizing this place: electricity, modern plumbing, air conditioning. I hate to say it, but it would probably have been less expensive to build a new house from scratch."

"Ah, but it would lack the history this house has."

"You're right, my dear. How about a tour of the place, Quinn?"

"I suppose so," his daughter halfheartedly replied.

For forty minutes, the family of three went from room to room, and Rosanna described what she had in store for each one.

"What's in there?" Quinn asked, pointing to a door that her mother had ignored.

"It was once a bedroom, but it's so drafty in there. Maybe your father will use it as his home office," she suggested.

But there was something Max Rupert found oddly disturbing about the room.

"I'd rather use the former vicar's office on the ground floor. We can keep this one as a guest room."

When Quinn crossed the threshold, however, she immediately claimed Terrence Kilbourne's former bedroom as her own.

"I suppose I could paint it pink, and maybe get a canopy bed for you and a vanity," Rosanna said.

"No. I don't want anything girly. I'm getting too old for that. Besides, I think it has character the way it is," Quinn opined, looking out the window at the abandoned graveyard that, with the exception of the parsonage, was all that remained on the moorland after the church was destroyed by an aerial attack during the Second World War.

Who knows? Maybe the atmosphere here will inspire me to write, she thought, as she felt the unseen presence of Terrence's spirit, which still took shelter within the sanctuary of its walls. Or maybe I'll try my hand at painting instead.

No matter what Salem may say, Terrence Kilbourne never painted a headstone like his one.