The Anchoress

As one of the four daughters of Sir Guy Payne, Baron of Aldwick, Isabel was expected to wed a man of her father's choosing. Her three older sisters were already married. In each case, the union benefited the Payne family, either financially or politically. Isabel, the youngest, would soon be promised in marriage to a man she did not know, let alone to one she loved. The girl—scarce old enough to be called a woman—dreaded the idea of becoming a wife.

"I don't see why I have to marry anyone," she complained to her mother one day.

"Don't be silly," the Lady Elizabeth chided her. "You were born to be a wife and a mother."

"Like my sisters?"

"Yes."

"And be miserable, too?"

"Your sisters are not miserable."

"They're certainly not happy. Cicely is married to an old man, four times her age."

"Who is very wealthy," her mother needlessly pointed out.

"And Matilda is married to a man whose girth is greater than his height. I hear he spends the entire day, from sunup to sundown, eating and drinking."

"He, too, has great wealth, as does Eleanor's husband."

"Poor Eleanor fared the worst of the lot. She is married to a cruel man who beats her."

"Don't you go spreading rumors. You don't know that for a fact."

"Don't I? I've seen her bruises with my own eyes. I tell you he beats her, and he takes great pleasure in doing so."

"Eleanor must learn to deal with her husband, then."

"I can only imagine what kind of man Father will select for me. Probably an ogre."

"But I have no doubt he will be a landed ogre, and you will be the mistress of a grand castle."

"I already live in a castle."

"You can't expect to stay here forever! No, my dear, it is either marriage or a nunnery for you."

"Rather than be bound to a man like one of my brothers-in-law, I'd sooner take my vows and live in a convent."

To Lady Elizabeth the idea was ludicrous. Her youngest daughter was beautiful, vivacious, intelligent; and, even when she was being headstrong and willful, she was her mother's favorite child. If given the opportunity, Elizabeth would gladly keep Isabel at home, but that would be selfish of her. The girl needed to live her life, not to run away from it and cower in fear of a bad marriage.

"You should have been born a boy," the exasperated mother said. "Then you could have become a knight like your father and gone off to defend the Holy Land from the infidels."

"Why should my being born a female make a difference? If I were to wear a suit of armor, who would know my sex?" Isabel asked.

Lady Elizabeth shook her head and threw up her hands in frustration.

"The sooner you are married, the better off everyone will be."

* * *

To say that Isabel woke up that morning would not be accurate, for she had not slept a wink the previous night. Instead, she lay awake in her bed, praying for divine intervention.

Today is the day I have long dreaded, she thought, as her servant helped her don her finest garments. I am being offered up like a fatted calf.

After much consideration, her father had chosen to give his daughter in marriage to Sir Baldwin Marbury of Ayershire. Although the two had never met, Isabel made no attempt to imagine what Baldwin might be like. She saw no reason to torture herself with dreams of a young, handsome and chivalrous knight. No doubt her sisters had had their hearts broken by doing so. Besides, what was the point? She had already decided to stoically accept her fate—whatever it may be.

Who knows? she wondered pessimistically. Maybe I'll die young, and my ordeal will come to a swift end.

Lady Elizabeth bustled into the girl's bedchamber and asked, "Aren't you dressed yet? Sir Baldwin is downstairs in the great hall, eager to meet you."

"I'm almost ready," her daughter replied, her voice lacking all signs of emotion.

"I think you'll be pleased with your father's choice of husband. He seems to be a nice young man."

Silence. It was not like her daughter to pout.

"Smile," Lady Elizabeth advised. "I'm sure you'll find out that things are not as bad as you imagined."

The well-meant words fell on deaf ears. Like a sacrificial lamb being led to the slaughter, Isabel followed her mother down to the great hall. She kept her eyes down, not out of modesty, but from dismay. How she wished the meeting could be indefinitely postponed.

"Ah, there you are, Isabel," Sir Guy said jovially. "Come meet the man I've chosen to be your husband."

When she eventually raised her eyes and beheld Baldwin for the first time, it was as though the dark clouds in her life suddenly vanished and she was bathed in warm, bright sunlight. The amiable and highly attractive knight then smiled at Isabel, and her knees became weak.

The days, weeks and months that followed that first meeting were the happiest in Isabel's life. For years, she had foolishly fretted over the prospect of marriage, only to fall hopelessly and totally in love with her intended spouse.

My poor sisters, she thought on her wedding day as she and Baldwin stood before the bishop and exchanged their vows. How sad that they have been so unfortunate while I have been truly blessed.

Three days after her marriage the celebrations came to an end, and Isabel journeyed to Marbury Manor, her husband's home. It was not the ornate, sprawling baronial castle of her birth and childhood, but it was a large estate nonetheless. She sincerely believed she and Baldwin would make it a happy home.

I have no doubt we will soon fill the place with children, she thought, beaming with happiness.

Unfortunately, the bride's happiness was not to last, and her dreams of a long and happy marriage would remain forever unfulfilled. Before the day marking the couple's first anniversary arrived, Baldwin announced that he was to accompany King Richard to the Holy Land in an effort to retake Jerusalem from the Muslim leader Saladin. Although Isabel knew that duty to king and God set Baldwin upon this path, she hated to be apart from her husband.

"You must have faith, my love," he said at their moment of parting. "Trust that I will do everything in my power to come home to the woman I love. Yet if I do not live to return to England, be assured we will have all eternity ahead of us."

Isabel did her best to remain strong and to believe in the sacred cause her husband was fighting for. Many an hour she spent in the chapel, praying for his safety and a speedy homecoming. In fact, she was on her knees beseeching the Virgin Mother for his safe return when she received word that Baldwin had fallen in the Battle of Acre.

* * *

Although Lady Elizabeth felt compassion for her daughter's tragic loss, she took a pragmatic view of the girl's situation. Isabel had been mourning her husband for more than a year. It was time she put aside her grief. Life was too short to wallow in self-pity.

"Sir Alistair is a good choice of husband for you," she announced when the young widow returned home for a visit with her family.

"I'm not interested in entering into another marriage, least of all with a man who already has five children."

"Those five children need a mother, and you're a woman in need of a family. Besides, you and Sir Alistair have much in common. He lost his wife and you ...."

"No, Mother," Isabel steadfastly insisted.

"What will you do then, take the veil?"

"Not exactly. I don't think I'm cut out to be a nun. I want to become an anchoress."

Her daughter's response took Lady Elizabeth by surprise.

"Surely you don't mean that! Why would you shut yourself away from the world and forsake all those you love?"

"Much as I would miss you, Father and my sisters, I want to spend whatever time is left to me on earth in prayer and contemplation."

"My dearest girl, you are grieving now, but in time you might feel differently. You might meet another man who touches your heart as Baldwin did."

"I could never love anyone like I did him."

"I beg you not to take such a drastic step. There's no going back should you change your mind in the future."

"I'm sorry, Mother, but just as God chose my husband's path, he chooses mine, as well."

Lady Elizabeth knew the streak of stubbornness that ran through her youngest child, and realized her arguments would not change the girl's mind.

"I suppose your father will have to speak to the bishop then."

* * *

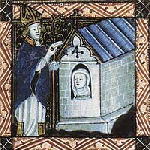

Two day's journey from the baron's castle was a village that was home to the Church of St. Thomas. Within weeks of Isabel's decision to seek refuge in a reclusorium, the elderly woman who lived in St. Thomas's anchor-hold breathed her last. In light of her passing, the bishop granted Isabel's request and assigned her to take the dead woman's place.

As was the case with many aspects of religious life in the Middle Ages, there was an established ritual to be followed. In this case, it was an enclosure ceremony. It began with fasting and confession. Then Isabel had to attend mass, lying prostrate on the floor in front of the altar. Afterward, the congregation accompanied her to the anchor-hold, chanting while she held a lit taper to metaphorically light her way.

When the procession stopped at the temporary opening in the wall of the anchor-hold, Isabel looked inside the small room that jutted out from the main edifice of St. Thomas's, a place that was destined to be her cell for the remainder of her natural life. It contained only a bed, a chamber pot, a private altar and a crucifix. As required by custom, there were three windows. One opened into the church so that Isabel could benefit from its religious services, take communion and offer confession. Another permitted food to be passed in and refuse to be taken out. The last one was used as a means of communicating with the outside world. Although covered by a cloth curtain, the opening allowed people to seek her guidance and request her prayers.

Lady Elizabeth held her breath, hoping her daughter might suddenly change her mind. When her child turned toward her, however, there was a look of determination on her comely face. The mother barely managed to hold back her tears as the solemn rite commenced.

After the bishop administered last rites, Isabel took part in a mock funeral to represent her altered status. By becoming an anchoress, she was, in a religious and social sense, dead to the world. Lady Elizabeth turned away as her daughter stood in a shallow grave, unable to bear the sight as dirt was thrown over Isabel's feet. Finally, at the conclusion of the ceremony, the young widow entered the anchor-hold. The opening in the wall was sealed, and the new anchoress was entombed in her cell.

With their youngest child as good as dead to them, the baron and his lady returned to Aldwick. By order of the church, there were to be no letters, no visits and no word of the girl's wellbeing. From that day on, whenever they spoke of their youngest daughter, it was to be in the past tense. To soothe their pain, they erected a monument in memory of Isabel in the local churchyard, where generations of family members were buried.

Despite her parents' misgivings, Isabel found peace and solace in the anchoritic life. She did not mind the plain clothes she was expected to wear or the simple vegetarian diet she given to eat. Nor did she shy away from the occasional self-imposed physical discomfort, knowing such pain would benefit her immortal soul. The luxuries of being a baron's daughter and a knight's wife had ceased to appeal to her once Baldwin died. Most of her day was spent in prayer, but she also had opportunity, when light permitted, to read or embroider.

As the months turned into years, the anchoress took comfort in her religious duties. Considered by the people of the village to be a wise woman, she was able to give advice, hope and comfort to the villagers who appealed to her from the other side of her curtained window. Having known heartbreak in her own life, she was eager to help alleviate it in others. Yet, according to church rules, she remained a hermit, cut off from family and unable to make friends. No one besides the bishop knew her identity or saw her face. To all else, she was a woman of mystery.

In the evenings, after finishing her simple supper, Isabel's thoughts would turn from the villagers' lives to her own. With the twilight sky making the interior lighting too dim for reading or needlework, she would often gaze out at the church graveyard. It was the only view she had of the world beyond her cell. In that eerie setting, at a time in-between day and night, ghosts from the past haunted her. She remembered her sisters, not as unhappy wives but as childhood playmates. Her mother's face was young and beautiful, not careworn as it had been the last time she saw her.

Should something happen to her or to any of my family, I'll never know it, she thought. Why, it's possible that even now one of them might be ....

The anchoress pushed that thought from her mind. It was much less painful to think of the present or the future than to recall her past.

The former anchoress is buried there, she mused, looking at the tombstones. I wonder if that's where they'll place me when my time comes.

The thought of her own death did not sadden Isabel. On the contrary, it brought only happiness to her; for she was certain that when she closed her eyes on this world, she would open them to Baldwin awaiting her in the next.

* * *

In her self-made tomb, Isabel lost track of the days. Her only reference to the passage of time was the changing of the seasons. By her count, six winters had come and gone since she entered her cell adjacent to the Church of St. Thomas.

The anchoress was cold and tired. It had been an emotionally exhausting day. One of the women in the village had taken ill and would most likely not live out the week. For hours, Isabel had prayed on her knees on the cold, hard floor for the woman's recovery.

She is a widow with five young children, she thought forlornly. What will happen to them after she is gone?

After finishing her spartan meal, she opened the cloth curtain and peered outside her window. The evening sky was a deep indigo in color, and the landscape was painted in shades of gray and black. The leaves on the trees had already begun to fall, and there was a chill of autumn in the air. Soon it would be winter again, and snow would cover the ground.

Isabel closed her eyes and imagined the white-covered hills of Aldwick, the ice-laden trees glistening as though encased in crystal. She remembered the holiday seasons spent with her family and the one and only Christmas she had shared with Baldwin at Marbury Manor. Tears fell from her eyes, and she lowered her head in prayer.

"How much longer must I stay in this world without my dearest husband?" she cried. "Why can't I be the one to die instead of that poor mother with the five children?"

The sound of an approaching horse rescued her from her morose reverie. She quickly shut the curtain to prevent the rider from seeing her. Given the lateness of the hour, he was most likely on his way to the church and not to the anchor-hold. Still, she believed in taking precautions.

Isabel was about to lie down on her bed in preparation for sleep when she heard a voice at the window.

"Lady Anchoress," it called softly. "Are you awake?"

"Yes," she replied. "What is it you want?"

"I have heard many stories of your goodness and compassion."

The man's words were hard to decipher, for he spoke with difficulty. Isabel assumed he was ill, or perhaps he had been born with a deformity of the mouth.

"So you have come to ask for my prayers?"

"And for your consolation."

"You have had a recent loss?" the anchoress asked.

"It's not actually a recent one; my dear wife has been in her grave for several years already. But I just learned of her death."

"How is that possible?"

"I was away for a long time, and it was only upon my return to England that I received word of her passing."

"Your tale is a sad one indeed, good sir. I will pray for your wife's eternal soul and for your peace of mind."

"Thank you, kind anchoress."

"God be with you, good sir."

"And with you."

Isabel heard the light crunch of the fallen autumn leaves as the knight walked toward his horse. The animal whinnied as he mounted it.

"Come, boy," she heard him say. "Let us continue our journey back to Marbury Manor."

The anchoress caught her breath upon hearing the man's words.

I must have misheard him! He couldn't have said Marbury Manor!

Her trembling hand pulled back the curtain. Despite the pronounced scar from the sword wound that had cleaved his cheek and mouth, she had no difficulty recognizing her beloved Baldwin. There was no mistaking his eyes.

"Baldwin!"

His name came out of her mouth as a mere whisper of amazement.

When he spurred his horse, she realized she might never see him again—not on this side of heaven, anyway.

"Baldwin," she called out in a louder voice.

Then she screamed his name at the top of her lungs.

"Baldwin! It's me, darling: Isabel. I'm not dead. Come back."

Her words were lost to him, though, drowned out by the sound of the horse's hoofs as he galloped off into the night.

He can't go, she thought, her panic mounting as the distance between them grew.

Since the two exterior windows were both too high and too small for her to crawl through, she tried to squeeze her body through the interior window that opened onto the church. She managed to get her head through but not her shoulders.

"No!"

Like a madwoman she began clawing at the stone wall, hoping to break through what once had been the temporarily opening through which she entered the cell. All she succeeded in doing, however, was scraping the skin from her fingers.

"Help! Let me out," she shouted, hoping one of the villagers would hear her. "Please, God, get me out of here!"

* * *

When the elderly Sister Agatha left food at the window of the anchor-hold the following morning, she was surprised to see that there was no waste left for her to dispose of.

"My lady?" she called through the window. "Are you awake?"

When the nun pressed her head to the opening to listen for sounds of life, she could hear someone breathing inside the cell.

"I've brought you something to eat."

Isabel still did not answer.

Fearing for the anchoress' wellbeing, the nun went in search of the priest. He, in turn, opened the interior window and saw Isabel kneeling on the ground, her hands clasped in prayer.

"She's all right," he assured Sister Agatha. "She's at her prayers."

Then he noticed the young woman's bruised, bloody fingers.

"Have you hurt yourself, my child?" he asked the anchoress.

Like the nun, the priest received no response to his inquiries.

"Perhaps we ought to send for the bishop," he said.

"How long has she been like this?" the bishop asked the priest when he arrived at the Church of St. Thomas.

"Sister Agatha tells me the anchoress appeared quite normal when she brought the evening meal to her yesterday, so apparently something came over the poor woman during the night."

"Send to the village for some workmen to break through the wall of the anchor-hold. We have to get her out of there."

After the bishop had the opportunity to closely examine Isabel, he determined that she could neither hear nor speak. Furthermore, he was not entirely certain she could see since her eyes remained closed. Her lips moved in prayer, but no sound came out of them.

"Bring her something to eat," he told the nun.

"We tried to feed her," the priest explained. "She won't touch a thing."

"Force the food down her throat, if necessary. If she doesn't eat, she'll die."

Isabel chewed and swallowed the food when it was put in her mouth, but she made no attempt to feed herself.

"If we put her back into the anchor-hold, she'll starve to death," the bishop declared. "We'll need a new anchoress."

"And what are we to do with her?" the priest inquired.

"Find a place for her in the convent. The sisters will take care of her."

* * *

For close to eighty years, the former anchoress of the Church of St. Thomas remained at the Convent of the Holy Mother. The nuns there not only fed her, but they bathed and dressed her, as well. There were brief periods when physical exhaustion hit her, and Isabel would fall asleep on a bed of straw placed in her room. Most of the time, however, she remained on her knees with her hands clasped in prayer.

"It's a miracle she's been alive for so long," the mother superior said to the novice who had been assigned to see to the old woman's needs. "She must be over one hundred years old by now."

"I've heard there's talk of the church making her a saint after she's gone," the young nun said.

"It seems fitting. After all, she's devoted most of her life to praying for others. Now people will pray to her."

What the good sisters of the Convent of the Holy Mother did not know was that Isabel's prayers were not on behalf of others. Since that long ago evening when Baldwin appeared at her window as though resurrected from the dead only to disappear into the night, the anchoress remained a prisoner in her cell—not in body but in mind.

For the next eight decades, her eyes remained closed and her hands remained clasped, as she prayed over and over again, "Please, God, get me out of here!"

This story was inspired by actual accounts of anchoresses in the Middle Ages who were walled up in small cells [anchor-holds] connected to churches in England. They underwent symbolic funerals and burials and were considered dead to those who knew them.

Taking inspiration from one of my ancestors who was an anchoress, I once walled Salem up in a room in my saltbox, but he managed to cast a cat flap spell and escape.