Chapter Three

Neon Eats

Dust, dirt, diesel, and dead flies on the window sill…”Order Up!” That was 1965. The diner was packed and Doc and I just got off a ride from Barstow to Rogers, California and could smell the calories on the grill I so desparately needed. By 1984 she was down for the count and although I hadn’t been there in almost two decades, a friend of mine, Frank Cisco from the Siskyous did and wrote me this letter….

Sandoz:

Lot’s have changed Amigo with the place. I remember you tole me about this place and it is calorically magical and now that I a too am a journalist, though still learning, wanted to visit you this summer and decided to stop here and see the place and see how the locals, what’s left think of it and how their lives have changed subsequently. Hope you don’t mind me stealing a story from you.

Frank

Dust, dirt and diesel, dead flies on the window sill...."Order up!"

The diner's rusted neon sign had long ago bled dry; evaporated along with the flowing stream of highway traffic that used to flood the two lanes of the now cracked, aged California concrete. In it's day in another era, it was a two-lane Mississippi river of commerce as migratory tourists searched every prarie dog hole for those elusive invisible jackalopes that don't really exist and stacks of cutesy, kitschy "wish you were here" postcards to send home from the open road to the folks back home in cold, frozen, plaid and proud Minnesota.

Khaki clad GI's ready to lock n' load poured across the desert two-lane on their way to Ord and Longbeach ready to train and end the war, any war. They jammed the jukebox with quarters, musical ammo snug in the slot, as the lonesome whistle country blues sounds of Hank Williams rose like an angel on wings, and Bill Haley one o'clocked, two o'clocked, and three o'clocked around the clock.

That, however, was before the intrusion of the interstate. The Red Ball Highway that won the war in Europe, now declared war on the American Southwest, decimating the diners, cafes, gas stations and warm beer juke joints. Blew them to smithereens with a steady, unrelenting bombardment of four lane super highways. Artillery shells of progress and prosperity, exploding, leaving the legendary two lanes, bleeding and lifeless, debris now, relics with fading signs on forgotten, forlorn, rusted and abondoned on old roadsides.

Hollywood itself, all glitz and glamour, stopped by the old place back in the heyday '30s. "Hell, Clark Gable hissef' et here once I'm told by my Grandpappy. Yep, him and Carol Lombard too on a couple o' occasions. Big cars and mink coats. Hoowee, them was the days, boy, them was the days. Ain't lak that now, though, I tell ya. Nope. Seems ole Ike, hell of soldier, President to, before that Catholic feller Kennedy got us all messed in Vietnam. My daddy voted fer Ike, but the General had this here idea you see, about that autobane or whatchacallit in Germany. Bigger cars, faster roads, people in too much of a hurry today if'n ya'll ask me. Anyways, done came through here in '66, maybe '67, and kilt the town. Now don't that beat all. S'pposed to be progress, and kilt the whole damned town. Shame is what it is, a downright shame."

The Roostertail Cafe had been a California desert landmark since 1930. Nobody was even sure where the name came from anymore, nor cared. Stan, along with Janet, his only waitress and also his wife and lifelong mate, ran the old place and tended to business, what was left of it, like his grandfather did when he opened it, and like his father did when he took over after Stans grandfather passed on to that great filling station in the sky.

Stan laughed, thoughtfully to himself. "What's so durned amusin' Stanley?" Only Janet ever called him Stanley; to everyone else it was just Stan or Stosh, a nickname he earned in Korea. He laughed again and banged the table with his hand. "Lifes crazy. Never thought I'd be running a restaurant, let alone a rundown one, and now, I get ready to sell the joint and I won't know what to do with my time. Live life like a broken down millionaire I suppose. Take up pottery or get a telescope and look at stars all night to fill my free time."

Janet smiled and let him have it. "Remember when you got home from Korea? Said you'd never settle down in the desert and stay put. Took a job on a Colorado railroad as a brakeman and damn near killed yourself, hated that. Then you made custom cowboy hats in Wyoming and you hated rodeos...but Lord, when you took over the cafe, why I've never seen you happier. You may think you hate this desert, but you don't, not really. You just think you're getting old, slowing down, running out of neon like that old sign out front, and well, you are, and I am and that's life." Stan smiled broadly and felt better, full of neon and full of memories, good and grand memories.

He remember the hustle and bustle of the old days, the good old days. Used to have small cabins in back, the diner itself a porcelain grease palace, stools and tables filled with cutomers talking about where they've been and where they're headed. East to West, West to East, North to South and South to North. Could hardly keep the gas pumps going. "Check the oil? How's them tires? No water for miles so better check that fer ya too. Goin' to Los Angeles, are you, well say hello to Mr. Gable when you see him for me. Stops here sometimes, yep, sure does". Some days there were so many Packards, Plymouths, Chevrolets and Fords, the supply couldn't keep up with the gas guzzling internal combustion demands of those piston pumping petrol hungry heavy metal mo-sheens on some days.

Big neon signs out front, like shimmering mirages in the heat of day, lit up the night sky for miles, brighter than Times Square on V-E Day. The cafe announced in simple easy to understand neon lingo, "EATS". The cabins beckoned with a big neon welcome, "VACANCY". The wooden cabins were filled at night with tourists glad to be off the road for a few precious hours of rest after keeping the beat to the steelbelt concerto. You could hear the childrens cacophony of muffled laughter in the knotty piners, parents laughing too, right along with them. The soft glow of the lamps within cozily illuminating the floral print of the cheap curtains.

Every now and them, the urbane family, constrained and shackled by months of claustrophobic skyscraper concrete, would walk, float in a dream state out onto the gravel parking lot at night to wonder in awe at the horizon to horizon palette of stars that filled the clear desert sky, natures nocturnal canvas. The succulent smells of the sand plants, the crisp, black night air..The Cactian Kingdom of the Great Southwest.

Next morning, refreshed, born again, they'd pack up the car and then head into the cafe. The flickering neon sign still on in the fading early morning hours as it made ready for the briliant sun and the heat of the day. "EATS" was all it said, all it ever said. Story goes that when asked why it didn't say more, Stans grandfather replied, "It says enough." The customers would wolf down big plates of fresh eggs cooked to cuisinal perfection, drink coffee strong enough to wake the dead, and feast on peppered bacon and thick slabs of sourdough toast with fresh butter and jam, homemade by Stans wife.

Afterward some would buy some to-go food for the road, long trip afterall. A postcard or two with a cartoon character Navajo chief on it, taffy candy and small pecan rols in a bag for the "are we almost there yet" kids in the back. They would then pull the cars and campers around to the pumps, fill 'em up, have the oil and tires checked one more time for good measure and buy a .25 roadmap to help guide them to the Pacific Ocean across the sea of sand they had to cross first.

On occassion, to have some fun with the tourist, Stans grandfather would sell the kids souvenir bags of "rattlesnake eggs" and stuffed toy rabbits with antlers glued to their synthetic heads. "Jackalopes is what they is. Lot's of 'em round here." The kids eyes would get wild eyed wondered, and the parents would smile at this obvious farce and tall tale. Road ready, mom and dad would load the kids, along with a bag full of memories, genuine rubber injun tommyhawks, plastic feathered headdresses and rubber tipped arrows for plastic bows and maybe a coonskin cap or two for good measure. Never know what you'll run into out in the mirages and heat of the merciless Mohave.

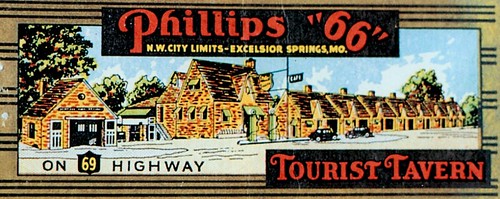

The town of Rogers, Califonia was a thriving port in the automotive seas in those days. Hardware store, merchantile for linens, grocery store for food and even had a a small pharmacy in back. The Roostertail had one of the first soda fountains in California, and experimented once with bringing food out to the waiting cars to speed up service and increase profits. Grandfather noticed though, that then the harried motorists would hurry on their way, the cabins would sit vacant. He quickly but an end to his experiment marriage curb service socialism and carhop capitalism.

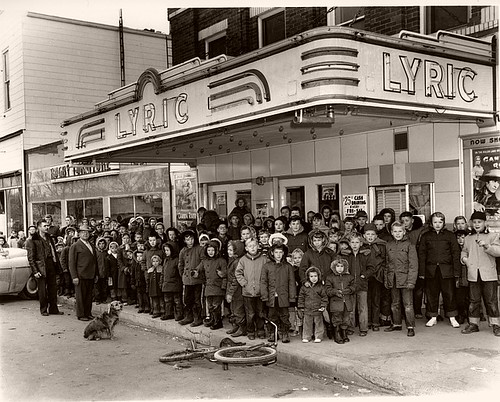

The old movie theater in Rogers advertised "100% Refrigerated Air". The Carswell family, who had opened the small theater in town just before the war, opened a drive-in movie theater in 1949 on some ranch land they owned. Showed all the latest films from Holly-wierd, and by the mid-50's the kids started to come from miles around, sometimes from as far away as Eastvale in the next county on Saturday Nights. It was a revved up processional of souped up '32 Fords, '49 Mercs and '57 Chevy's.

The movies sooned changed, and Errol Flynn was swashbuckeled by an atomic monster from Japan called Godzilla. Families that had enjoyed cartoons, shorts and main features now kept away, as the kids enjoyed sexual discovery and paradise by the dashboard light in the backseat vinyl with rock n' roll on the radio up front. On the silver outdoor screen, Bugs Bunny bested Elmer Fudd everytime. and who could resist the magnet of madcap that transfixed us with the eye-poking doink-doink "Soitenly!" mayhem of the Three Stooges.

"Times was good" the oldtimers chime in, but the times, as the song says, were a changin'....

The coming of the Interstate also brought with it a social whirlwind of change. The next generation of Rogers progeny realized they didn't want to farm or ranch anymore. Profits were too low to eke out an existence and prefered perfume and cologne to the smell of manure. Some went on to college, others joined the Army to to stop the Communist Domino that was devouring Asia, and others just simply left town and dropped off the face of the earth as they knew it, never to be seen again.

Some of them were plowed under the subsoil of finance, to the banks, and others sold out to corporate farms and huge behemoth American conglomerates. Sold land, pennies for the dollar just to get out from under.

Families moved away, back east to places like Indiana and Illinois, for God's sake, richer farm land to be sure. As the towns population was let out like air in a slashed tire, the merchants too began to feel the loss. Had to cut back on merchandise and service. Raise prices on products that nobody could afford anymore.

If you listen closely to the past, you can hear the voices of a family traveling on vacation. The radio on, tuned to some obscure daytime AM station in the middle of the desert, in the middle of nowhere. Count Basie pounding out the beat to perfection. The preachers voice, loud and proud looking for donations while preaching everlasting salvation. The kids making contorted faces at passing motorists. Time to stop at that cafe, been here a thousand times before on this road, but have to get fuel for the car anyway, and grab one of those giant burgers and homemade fries. The creme soda is also to die for.

The years passed. The kids have grown and gotten married and have families and little face contorters of their own now who rule the backseats and still ask, "are we almost there yet?" The families get together, as always for the holidays, sit through innumerable hours of 8mm film and Kodak slides, and reminisce about the good old days. Like clockwork, the conversation invariably gets around to those wonderful old roadtrips. "Remember that diner we used to stop at, in Rogers, in Califonia I think, and those huge burgers? Those were great burgers. I wonder if it's still there?"

The Rogers school too now stands empty, a panhandler, a hobo on the side of the tracks. Crumbling concrete and the phantom sounds of ghost football voices that cheer no more on Homecoming Night. The echoes of the past still reverberate through the empty, decaying halls. The windowless facade stares from empty eyesockets as though seeing the past as clearly as we see the present." I think it was '39" say the oldtimers. "Yeah, it was '39..that year we won the division in football..what was that kids name? God, he could run."

The school emptied itself of seniors every year, out to the cold world, away from the warm blanket of youth, scholastic routin, friends and familiarity. Some to college. Some to war. Most, all married now, blown and scattered across America like dandelion seeds. Every now and then someone pulls out the Yearbook from a box stored in the attic, opened slowly and carefully as though a rare Guttenberg bible, centuries old that threatens to crumble like a rotted shroud. Each page studied carefully. A smile here, a tear there, then recognition.

"Yeah, I told you it was '39. Billy, that was his the kids name. Got us the champeenship that year." Then a pause and a sigh. "Billy died in '43. Okinawa I think, just a kid at the time. Man could he run". As you walk by the empty school now you can almost hear the cheering from the stands as Billy's memory lives on today. Man, could he run, but not fast enough.

The drive-in is gone too. Weeds fill the empty lot, the old screen is tattered and aged, like the Gloria Swanson character in Sunset Boulevard still waiting for her closeup Mr. DeMille. The speakers were stolen or sold for scrap long ago, and the concession stand a testimonial monument to vandalism. Instead of the roar of Godzilla, now all one can hear is the scream of the wind at night as it blows through the empty lot, once full of life, teenaged angst, sexual discovery, heavy metal and chrome.

A lot of the merchants folded up long ago, to seek new fields of retail riches. The town, once numbering 365, now was somewhere around 62. Two lane tumbleweed riding the asphalt that remained, heading out to nowhere in particular towards the endless horizon. Some of the remaining townies had been here since birth and would remain until their death, cluthing the past in their hands.

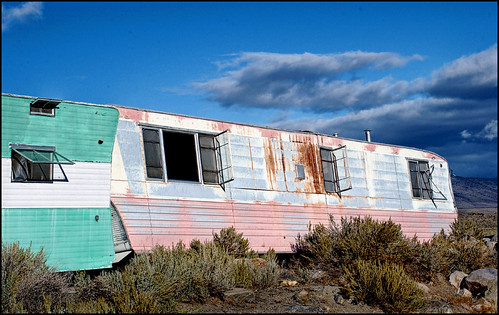

Sadie, who used to ranch with her husband Earl, for long hard hours until he died in '72 was now "the crazy lady" who lived in a broken down trailer with no running water but plenty of warm booze to numb her and give her comfort. The property they owned had long ago gone into forclosure, and what little money they had saved up went to pay for his burial and her seemingly endless supply of soul burning Vodka.

In the good years, she hauled bales of hay to the far reaches of the spreading fields. Hungry livestock came at a quick pace when she was spotted bumping along the field. Ernest Tubbs' new record was out and it played on the lonely country gospel station, KPSD. Earl heard that song for first time on the Opry driving that old truck at night, that magical analogue time of the evening when WSM in Nashville would fade in and out on the radio half a continent away.

The farm was filled with supplies most of the time brought in from town. Food, grains, feed, fertilizer, gingham and always, a little present for Sadie. Earl always hid it under a sack, and when he pulled up in the truck she would smile because she knew it was there. On the stove, Earl's favorite meal was cooking, her present to him. They both worked hard not only at the farming and small ranching but at making each other happy. He's long dead now, and she sold the land and moved to town. Earl still lives in her heart, and together, they're never far from that farm, a piece of them still remains on that land and will be there for a long time to come....until Crazy Sadie finally drinks herself to death.

The meat markets gone too. You could always get more than just the freshest meats in town. You also kept up on the latest gossip in the neighborhood. Turns out that "nice" boy the Carson girl's been dating is AWOL from the Army and been arrested. Did you know Sally Hellstom is pregnant again? Also heard that one of them new fancy supermarkets is coming to town, at the edge of the road out by the Meyers property.

Sure, some folks will go there at first, check it out, buy a few things, but in the end they'll come back here. Why, I have the freshest meats in the entire county. They'll be back, you'll see. Say did you hear about the Peterson boys? They got in trouble again.

Stan stared at the heat outside through the dusty windows, A Johnny Lee song on the jukebox. Thought about selling the place for years, and finally did, to one of those large interstate truck stop chains. Been home for years, but now, nothing left, but home is where the heart is afterall. Some of the oldtimers still stop by to chew the fat and the food, truckers mostly who still lament the passing of the old days too. Jake brakes and exhaust mingling with the jukebox and the grease from the grill. He smiled and wondered what they would do with that old neon sign that didn't work, hadn't worked in years.

The town that was so full of life once, was now just an Exit number on a roadmap. An old decrepit joint in the middle of the nowhere desert soon to feel the crash of the wrecking ball. Memories and road ghosts of the past, mixing with the dust, diesel, and dirt, and a few dead flies on the window sill...order up!

Crazy Sadie summed it to Stan one day, not too long ago, when he debated on fixing the place up for one last hurrah. Even having the neon recharged in the old "EATS" sign.

She just looked at him incredulously, cackled her cracked laugh and said "Boy, they aint no need for no neon no more".

CHAPTER FOUR - HUEVOS WHATEVEOS