The second to last of her Goldwyn films, and released in Apr. 1921, What Happened to Rosa is an entertaining light comedy. In its time, it probably passed for what we would today think of as a “sit-com.” Though fairly frivolous fun without pretension, it is not without its finer Goldwyn touches. Directed by Victor Schertzinger, who supervised all of her later Goldwyn films, the mini-feature concerns a hum-drum department store employee, Mayme Ladd who, after visiting a crank clairvoyant, in private imagines herself to be a mysterious Spanish beauty named Rosa Alvero. Mabel then is consequently given the unusual opportunity to play two distinct roles at once. In some respects, What Happened to Rosa is a more pleasant and enjoyable than her later Sennett endeavors because she is emotionally more “light on her feet.” Although noticeably more slow in acting and reacting than before, she is still fluid in her movements, and does not seem to be suffering from the off-screen distress that is so sorely apparent in subsequent films. Curiously, there is no obvious suggestion of any health problems in Rosa -- other than an overly glazed expression in one brief store-counter scene.

For first time in her films -- though by no means the last -- she comes across as too old for the part. Far from being convincing as a silly shop girl, Mabel usually looks more like the astute and worldly sophisticate she had become. Hence, her “Rosa Alvero” is considerably more convincing than her “Mayme Ladd.” Mayme as a character is somewhat incoherent -- again largely because Mabel just seems too mature and experienced to be taken for a naïve girl -- a problem that was to mar most of her later films. Rosa, by contrast, is much more engaging and interest drawing. Moreover, the charm of the Rosa character is that she is not merely Rosa Alvero, but, more precisely -- and here’s the nice distinction -- she is Mayme Ladd day-dreaming that she is Rosa Alvero.

We get some idea of how Mabel approached such roles and tried to become her character from contemporary articles she reputedly authored, as in this excerpt from one such:

“…here again we come to the root of humor that I mentioned before: being human. That's being natural. When I played the part of a poor little hoyden in one of my pictures -- ‘Jinx’-- I tried to remember during the entire making of the production that I was a homeless little wretch grateful for kindness from anyone. In another picture I played the part of a little slavey who longed from the kitchen to reach the bliss of the grand ball-room upstairs. And when I reached there and played the part of a lady I tried not to forget that I had been a slavey a few moments before. Things puzzled me a little; I wasn't quite sure that what I did was the correct thing, but I was as good as the rest in my heart and proud of my clothes; oh, so very, very proud of my new, fashionable clothes!"

Similarly, two years later she wrote:

"Naturalness is the most important element in acting. To develop naturalness you must develop understanding of human nature. You must be able to determine just what a certain type of person would do in a certain situation.

Again and as stated, Mabel in Rosa, and for that matter most all of her subsequent films, is decidedly more slow to react. She is as pretty as ever, but her response to the comic circumstances is, to put it mildly, decidedly toned down and hesitant compared to “Keystone Mabel.” At times she looks simply bored. And while she still brings a down to earth sympathy to the role, the effervescent, vivifying Mabel of the Biograph and Keystone has effectively vanished.

Notwithstanding, the new Mabel is not without great charms of her own. Again, playing Mayme imagining she’s Rosa Alvero gives her a superb occasion to shine, and in scenes that are sometimes both lyrically charming and wryly amusing; in particular the sequence where, alone in her bedroom, she imagines herself with Dr. Drew (played by Hugh Thompson); and the masquerade ball sequences. Masked Rosa, appearing with fan in hand, descending the staircase is perhaps as stunning and in its way exotic a grand entrance as was ever film. With wonderful lighting doing much to achieve the entrancing effect, the only real fault of the sequence is its brevity.

On the regrettable side is a bizarre brawl with a street urchin, who understandably will not give up to her his clothes so Mayme can disguise herself. It’s absurd without being at all humorous, and merely serves to reminder us that crazy does not always mean funny. As well, Mayme's fawning on Doctor Drew -- to the bizarre extreme of attempting to get injured in an auto accident in order to see him(!) -- is distasteful and demeaning -- again, without being all that funny. As always she is interesting to watch, but these last 15 minutes, though as likable as the rest of the film in its way, are too devoid of comic substance to be enjoyed or taken very seriously. Rather than the story being resolved, it fairly evaporates on us to meager or no dramatic purpose.

Fortunately, though, the film's weaknesses are effectively countered by it strengths, and Rosa, unabashedly light fluff that it is, at least holds up well as an all around pleasing and diverting film.

Molly O'

“What Sam [Goldwyn] knew then, and what I didn't know, was that Mabel's cheeks were no longer as round as apples. She was thin. She photographed without her old time sparkle and bounce in recent pictures, not yet released which I had not seen. She was unhappy and ill and she looked it. We were amazed and upset when she reported for wardrobe tests.

That “she was still beautiful” might sound like perfunctory politeness. Yet odd as it might seem, she was also still beautiful in spite of her being “unhappy and ill” -- which as well was true. Yet she is beautiful in a different way. She is even less vibrant and athletic, and more understated and hesitating than in the Goldwyn (let alone the Keystone) period. In addition, in Molly O’ we for the first time see the sad Mabel Normand. This is all the more startling because this transformation occurs before either the Arbuckle or Taylor scandals had even taken place.

Naturally, it would seem to make sense to conclude that it was the alleged miscarriage referred to in Betty Fussell's book that brought about this despondency. How painful it must have been to have borne such a secret, few of us can hardly guess. And perhaps her returning to Sennett was an act of contrition of sorts. As for Sennett, apparently uninformed as he was as to the “real” cause of her unhappiness, there is a certain sense in Molly O’ that he is welcoming back the prodigal, although in a respectful and affectionate way. “Molly O’ ~ I Love You” reads the title of the sheet music promoting the film; as if the once rejected lover was receiving once more in his arms the earlier lost sweetheart with whom “fast living” (presumably) had wrought havoc.

Molly O’ was clearly intended to be a major effort by Sennett, and since it was the single film which in later years he wanted to re-do again, perhaps he thought of or hoped it would be his magnum opus.

The plot is less emotionally coherent than Mickey. Yet in its parts, Molly O' is often very touching and, albeit to a lesser extent, humorous. It has variety: light comedy, thrills, very serious drama -- everything but slapstick. Though the transition from the light comedy to serious drama is often handled awkwardly, and, much of the story fairly implausible, Molly O’, is, overall, a very rewarding film and, in moments, even powerful as a dramatic work. While its weaknesses are not to be brushed aside too casually, it, even so, it stands as a film of considerable and lasting merit. Director F. Richard Jones’ and or photographer Homer Scott’s use of camera angles, lighting, and close-ups, at the time, are usually uninspired. Yet Jones does have a knack for getting the most out of his players, and his orchestrating of scenes is often artful and imaginative. The very positive influence of D. W. Griffith, who had employed Jones just prior to Molly O’, is unmistakable, particularly in regard to the film’s highlighting of common yet visceral and timeless moral issues.

Although she obviously is devoid of much of her earlier pep, Mabel and all the cast in their roles are about as much as one could ask for. George Nichols, back from Mickey, and who years earlier had also directed for Griffith (including screen versions of Ibsen and other notable authors), brings a professional intensity to his role. Lowell Sherman’s Fred Manchester is as suave a screen villain as one I sever likely to watch. Jack Mulhall, Eddie Gribbon, Jacqueline Logan, Albert Hackett, Anna Hernandez, Ben Deely also are aglow with verve and give appropriate support.

As with her subsequent Sennett features, the story heavily relies on the Cinderella formula. Upper Class people (in a given instance rightly or wrongly) look down on poor Molly (Suzanna, or Sue Graham). Molly is in love with a young man who is someone of virtue, honor and courage. There are the usual stock characters, like the comic, tender-hearted mother figure, and the “other woman” with designs on the handsome young man. The villain pursues Molly (in this case amorously), and the well meaning but misguided, frowning father also threatens to ruin her perfect romance with the young man. But there is a fight and the film ends happily. All this, and Carl Stockdale as fairy godmother to boot!

Molly O’ is quite different from the traditional, medieval tale (or the fairy tale as it is usually known) in that it attempts to present the ordinary life of the lower class people in its harsh and unglamorous aspects. From the outset of the film, the poverty stricken tenement area and tension filled home in which the O’Dairs live is portrayed with almost documentary correctness. Not only does Molly come from a low income family, but she is the daughter of a washer-woman no less. The father, Tim O’Dair, for his part is a coarse and violent-tempered manual laborer, without the least bit of sentimentality about him. His junior work partner, Jimmy Smith, here comically played by Eddie Gribbon, is a cynical oaf he hopes to make his son-in-law without feeling it in the least necessary to consult Molly on the subject. To cap off the family portrait, her supportive younger brother, for all his good intentions, has a gambling addiction.

The villain and his accomplices are meaner and more callous than in Mickey. Though serving-maid Mickey is slapped by her cousin, Elsie Drake, for her disobedience, here Molly gets slapped by her father’s friend, Jimmy Smith, even though Smith had intended to marry her. By the same token, Mickey's fun loving Reggie Drake is almost a “nice guy” compared to the cruel and methodical Fred Manchester. This heightened atmosphere flavored with violence could be said to disturbingly reflect both the tension left over from the War and the onset of the Prohibition era.

Yet for all the realistic touches, the story is still basically that of Brother’s Grimm mixed with some D.W. Griffith.

Although Mickey and the Goldwyn film Joan of Plattsburg did allow her room to do some serious drama, in Molly O', more than ever before, Mabel has the opportunity to get into a role and situations with some real tragic possibilities. And but for her sometimes not looking well, she most of the time arises admirably to the occasion.

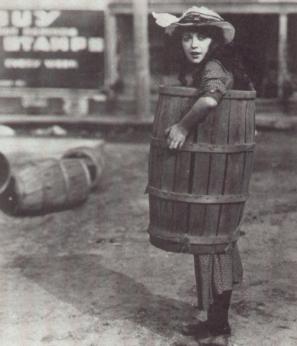

But coming into the role, there are some unavoidable difficulties. We mentioned previously her not looking well or happy. In addition to this, she is the internationally famous Mabel Normand -- 29 years -- old playing a laundry maid in her late teens or early twenties. As with Rosa, it is simply asking too much of an audiences to believe her in such a part. One clever way, and with a certain amount of success, Mabel and Jones gets around this is that there is a bit of caricature about Molly. She is somewhat surreal the way Chaplin and some of the Keystone creations were surreal: absurd, exaggerated characters in an otherwise real life world -- though, here, without the slapstick. In the opening sequences of the film, one is perhaps at first disappointed because Mabel is not all that convincing, that is, if we expect her portrayal to be realistic. Yet if we see Molly, with her wide dark eyes, wide floppy hat, and long Pickfordian girls (like Mickey), as not unlike someone out of a comic strip, then we are able to accept her within the story, and the rest of the film can proceed smoothly on this basis.

Early on, Mabel has some pleasant, quiet scenes, such as one at a park bench where Molly finds herself “philosophizing” with the “silhouette man,” played by Carl Stockdale. Here, where the message “dreams come true for those who believe in them” is openly declared, Mabel charms with her usual genial warmth. Nonetheless, other than this particular scene, most of the first half of Molly O’ (or what remains of it at least) is all fairly mechanical and serves mostly to set up the remainder of the story. It is not nearly so effective as that portion running from the masquerade ball sequences to the end of the picture.

A public masquerade ball (in those days not so unusual an occurrence) is held for charity, in which members of the different social classes come together to dance and revel. Against her father’s wishes, Molly sneaks off to attend the event dressed in a magnificent 18th century French-style court gown and wig (provided by the silhouette man.) Interestingly, the villain Manchester’s costume is of that of an effete dandy of the same period, while the hero, Dr. Bryant, by contrast, wears something more in the way of a medieval prince. At one point, Molly, stumbling in what she thinks is a back lobby, suddenly finds herself on center stage. A curtain suddenly opens up from behind, revealing her to the delight and laughter of the gathered throng of masqueraders. There follows a resounding outpouring of affectionate applause and cheers, not so much it seems for Molly (the story character) but for Mabel herself. One palpably senses and feels their effusive love for her; making this, no doubt, for many the most magic scene in the film. Perhaps what causes this sequence to be especially moving, and perhaps might also be considered one of the real themes of Molly O' is: Mabel from her heart loves and cares for all; and all (i.e. those in the cast and production generally) in turn love Mabel. It is genuinely sweet, and not mawkish as it might sound, because the feelings of both are undeniably sincere.

Molly, being mistaken for Dr. Bryant's fiancée (who is presently absent with her secret lover, played by Ben Deely), and Dr. Bryant are awarded as the most beautiful couple of the ball. All then are asked to unmask. In her own unmasking, Mabel is splendid -- there is clearly such a grand stir towards her -- again one feels it -- and she responds radiantly. It is a strange thing to try to describe, but a good analogy would be to a folded rose bud that, in a matter of moments, suddenly and wondrously bursts forth in glory (such as one might see with time-lapse photograph.) In this instance, it is Mabel's femininity and affectionate personality which blossom forth. The camera work, unfortunately, is rather flat. Otherwise it is one of the most memorable moments in all of her surviving films. The wonder, elation beaming from Mulhall’s eyes, almost to tears, in reaction to her, is clearly more than mere acting.

Molly is in many ways a spirited, yet somewhat worldly-wise Pickford innocent. At one point Sennett offered the script of Molly O’ to Pickford herself, who turned it down. Unlike the kind of young girl roles Mary Pickford is more commonly remembered for, Molly is to some extent allowed her sexuality; though the sexuality is suggested, without being in the least graphic or overt. It especially emerges in the form of a charming scene in which Dr. Bryant, after amorously strolling home with her from the masquerade ball, is about to depart as she ascends the threshold. As he is about to leave, she stands with her back against the door. He instantly returns and very tenderly kisses her forearm and that is bent outward upon the doorway. In sigh-filled trance, she permits the kiss; her womanhood (it could be said) having been woken within her. Just as Bryant departs, she turns aside and opens up her eyes to see her father glaring furiously at her. O’Dair then unleashes a violent tirade of anger and disgust. Nichols, as O’Dair, is more than convincing in the violence of his temper. So much so that one is tempted to wonder if his rage, almost to tears, may not, to some extent, have been inflamed by his (along with other people’s) real life displeasure with Mabel; or more specifically, disapproval of Mabel's earlier life (of abandon) away from Sennett. Incurring the wrath of her father in this manner, Molly packs her things and leaves home.

Next morning, Tim O'Dair starts off hot after Molly, correctly surmising he will find her at Bryant’s; and he is let in by the butler into Bryant’s wealthy abode. With a pistol in his pants pocket, and without giving notice of his presence, he finds Bryant shaving in the bathroom. Molly, dressed in bathrobe and pajamas, kicks up her legs on a nearby bed. The father approaches Bryant from behind as if to sneak up on him. But Bryant, seeing him in the shaving mirror, is able to surprise him before he can shoot. A fist-fight ensues, with Mabel as onlooker giving a Lillian Gish in distress performance, her eyes rolling upward into her head. Bryant finally knocks O’Dair flat, and it is revealed to the angry father that Molly and Bryant, after the ball, had already been married. The father, realizing that he almost just killed his son-in-law, breaks down ashamed and weeps. Molly then, in tears herself, caringly comforts him.

This is a bare and sketchy description of what are some momentous, tense, and moving scenes. All are superb here, particularly George Nichols who gives a heart-wrenching performance, and director Jones’ orchestrating the trio, and the drama of a daughter’s rebelling against her father in the name of love is not a little reminiscent of the kind of moralistic and poetic “photo-plays” done at Biograph in the early teens.

But wait…the film is not yet over. From the reconciliation of father, daughter and son-in-law, we are taken into a mini-serial episode, or perhaps more aptly the updated 1921 version of Barney Oldfield! If it is relevant to the main story, it is so in either a very tangential or abstract way. Otherwise it is quite out-of-the-blue, and is best taken as a kind of dessert to the main course. While these scenes with the blimp, and settling the gambling debt of Molly's brother, are not what we would call high-art, they are, nonetheless, exciting and even laugh provoking. Jones here sets on display his talent and flair for thrilling adventure sequences such as he would also later do in movies like The Gaucho (1927), with Douglas Fairbanks, and Bulldog Drummond (1929), with Ronald Colman. Though all -- including Mabel -- play their parts very nicely, Lowell Sherman, in particular, is a treat as the urbane and calculating scoundrel.

In sum, Molly O’, while certainly imperfect, is in its combining of unusual elements an imaginative and original film. We are most blessed and fortunate that it was not completely lost to us as had for many years been thought.

To Continue...

“In ‘Molly-O,’ for instance, I was given the situation of a girl from the slums entering a beautiful and luxurious mansion. What would my feelings be as a washerwoman's daughter coming into a beautiful kitchen? I would be curious, of course, and very intent upon the surroundings. I must not affect curiosity, I must feel curious. Then I saw the serving man taking cakes from a box and placing them on a plate. They were very good looking cakes, and naturally I developed interest in them. I wanted one terribly. For a moment my conscience argued with my appetite. I argued the thing over to myself. Then, suddenly, my hand shot into the jar and I took one and stuffed it into my mouth as though doing it while my conscience wasn't looking. After the first cookie, the process was easier. I couldn't get enough of them. There were several emotions in conflict even in such a little scene.

“The conflict of conscience and appetite, the fear of being apprehended, the delight at the first taste of a delicious cake such as I never tasted before, and the feverish haste with which I secured more of them and secreted them about myself.

“It is very easy to do such things after the business has been thought out by the star and the director, but the important thing is to feel the impulses that prompt the action. You must place yourself entirely in the character's place and feel exactly what she would feel in such a situation, otherwise your expression would fall short of realism and be nothing but ‘mugging.’ While watching an actress going through a scene on the screen, ask yourself whether or not you would do the things she does. If not, what would you do? How would you improve on her work? Wherein does her work ring false and why?"

“All those years of neglecting herself, of fun for fun's sake, had left a mark on a girl who was after all was very small.

“She was still beautiful. Her eyes still laughed….

“Mabel was happy with the cast of Molly O', especially happy with Dick Jones….Both Dick and I had long talks about Mabel late at night in the tower office. Mabel wasn't the same. She was ill.”