Leonard Maltin **** Films:

Leonard Maltin ***1/2 Films:

Leonard Maltin *** or "Above Average" Films:

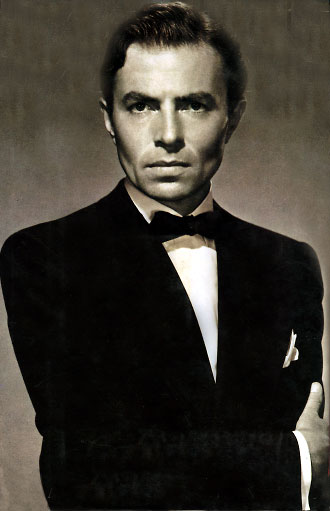

4. Alec Guinness

Alec Guinness de Cuffe was born on April 2, 1914, in London, England. He was raised by his mother, and never learned his father's identity. Although he appeared as an extra in Victor Saville's film Evensong (1934), his acting career was mainly confined to the stage (where he also debuted in 1934) during the pre-war period. After a stint in the Royal Navy during World War II, Guinness first gained notice in the small but important role of Herbert Pocket in David Lean's Great Expectations (1946), considered by many to be the definitive version of Dickens' novel. Guinness and Lean then re-teamed to film the definitive version of Dickens' Oliver Twist in 1948. (This film was banned for many years in many places because Guinness' portrayal of Fagin was considered anti-Semitic; on the other hand, it was banned in Egypt because it was thought that Fagin was made too sympathetic. Go figure.) After a supporting role in the classic British comedy A Run for Your Money (1949), directed by Charles Frend, Guinness gave what is considered to be one of the greatest tour-de-force comic performances in the history of cinema. In Robert Hamer's Kind Hearts and Coronets (1949), he played eight different members of the aristrocratic d'Ascoyne family (including Lady Agatha d'Ascoyne) who are systematically bumped off by jealous cousin Louis Mazzini (Dennis Price) in order for Mazzini to inherit the family fortune. Guinness' string of classic British comedies continued with Alexander Mackendrick's The Man in the White Suit (1951) and Charles Crichton's The Lavender Hill Mob (1951), the latter earning Guinness his first Oscar nomination for Best Actor (he lost to Gary Cooper in Fred Zinnemann's High Noon [1952]). Other comedic roles included G.K. Chesterton's priest-detective Father Brown in Hamer's Father Brown (1954) and Professor Marcus, one of a gang of thieves who tries and miserably fails to kill a sweet old lady (Katie Johnson) in Mackendrick's The Ladykillers (1955). One of Guinness' costars in the latter film was Peter Sellers, who would eventually replace Guinness as the versatile leading man of choice when it came to British comedy.

A replacement was needed because Guinness had decided to move into dramatic roles. His breakout performance in this respect came in Peter Glenville's The Prisoner (1955), in which he played a cardinal (known only as "The Cardinal") in an unnamed Iron Curtain country who is being grilled by an interrogator (known only as "The Interrogator") played by Jack Hawkins. The film brought Guinness a nomination for "Best British Actor" from the British Academy of Film and Television Arts (their version of the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences). 2 years later, another collaboration with David Lean made Guinness an internationally renowned dramatic performer. Lean and Hollywood super-producer Sam Spiegel (an Oscar-winner for Elia Kazan's On the Waterfront [1954]), together with blacklisted (and therefore uncredited) Oscar-nominated screenwriters Carl Foreman and Michael Wilson, were putting together an adaptation of Pierre Boulle's powerful novel Le pont de la riviere Kwai, and Guinness was cast in the key role of Colonel Nicholson. The book was the story of an artist (Nicholson) who cannot bear to see his creation destroyed, while the resulting movie, The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957), was a war film that also tried to be an anti-war film. In spite of a confusingly edited climactic sequence and a finale that explicitly states the theme (whereas Boulle simply implied it), the film was a huge hit, for which the beautiful photography (filmed on location in Sri Lanka), top-level performances, and generally intelligent writing definitely bear some credit. The film won 7 Oscars, including Best Picture for Spiegel, Best Director for Lean, Best Adapted Screenplay for Boulle, and Best Actor for Guinness. (Boulle, who also wrote the book that became Franklin J. Schaffner's Planet of the Apes [1968], was credited with the script even though he could not speak English. Wilson and Foreman finally received their Oscars in 1985 - unfortunately, both of them were dead at the time.)

In addition to his Oscar, Guinness won a Golden Globe and a BAFTA Award, as well as awards from the National Board of Review (his second, after Kind Hearts and Coronets) and the New York Film Critics Circle. Nevertheless, he did not give up on comedy, appearing in multiple roles in Frend's Barnacle Bill (1957), whose screenwriter, T.E.B. Clarke, had won an Oscar for The Lavender Hill Mob. (Many of these comedies were made at Britain's famed Ealing Studios, which is why their credits seem incestuous.) The following year, Guinness's first and only script was produced - an adaptation of Joyce Cary's novel The Horse's Mouth (1958), which was directed by Ronald Neame (Lean's former writer-producer-cinematographer) and starred Guinness as perpetually starving artist Gulley Jimson. Although the film caused riots when it first came out, it was critically praised and earned a Best Screenplay Oscar nomination for Guinness. 1960 saw Guinness in another praised performance in Neame's drama Tunes of Glory, from an Oscar-nominated script by James Kennaway. This film reunited Guinness with his Great Expectations co-star John Mills, and ironically, each played the type of role which had come to be associated with the other. Guinness' character in Tunes was a Scotsman - already something of a stretch for the London-born thespian - but he then further tested his versatility in Mervyn LeRoy's A Majority of One (1961), playing Japanese businessman Koichi Asano, who falls in love with Mrs. Jacoby (Rosalind Russell), a Jewish matron from Brooklyn. He then played Feisal, an Arabian prince, in Spiegel's production of Lean's Lawrence of Arabia (1962), a three-and-a-half-hour-long epic which inexplicably became an international hit and an acclaimed classic. Like almost all of Lean's post-Kwai films, Lawrence featured a long running time, a sweeping historical scope, epic production values, beautiful cinematography, multiple Oscar nominations, an all-star cast, and Guinness. It won Lean his second Academy Award and Spiegel his third.

Guinness joined two more all-star casts in Anthony Mann's The Fall of the Roman Empire (1964) - with Sophia Loren, Stephen Boyd, James Mason, Christopher Plummer, Anthony Quayle, John Ireland, Omar Sharif, and Mel Ferrer - and Lean's Doctor Zhivago (1965), which featured Omar Sharif, Julie Christie, Geraldine Chaplin, Rod Steiger, Tom Courtenay, Siobhan McKenna, Ralph Richardson, and Rita Tushingham. He also appeared in Peter Glenville's two follow-ups to Becket (1964): Hotel Paradiso (1966) and the interesting The Comedians (1967), which was adapted by Graham Greene from his novel and featured such notable black actors as Georg Stanford Brown, Roscoe Lee Browne, Gloria Foster (you may remember her from The Matrix), James Earl Jones, Raymond St. Jacques, and Cicely Tyson. Guinness then teamed up with Neame yet again for another Dickens' adaptation, this one a musical adaptation of A Christmas Carol called Scrooge (1970), in which Guinness played Marley opposite Albert Finney's title character. In Ken Hughes' Oscar-winning historical epic Cromwell (1970), Guinness was King Charles I, while he played two more authority figures in Anglo-Italian co-productions: Adolf Hitler in Ennio De Concini's Hitler: The Last Ten Days (1973) and Pope Innocent III in Franco Zeffirelli's Brother Sun, Sister Moon (1973).

Robert Moore's Murder by Death (1976), from a very funny script by Neil Simon, marked a return to good old-fashioned comedy for Guinness. A year later, he took on what would eventually become the role he is most associated with today. I am referring, of course, to Obi-Wan Kenobi in George Lucas' Star Wars (1977). This role, which immortalized Guinness among a generation to whom Kind Hearts and Coronets might as well have been the Minoans and the Mycenaeans, also earned him his fourth Oscar nomination, and first for Best Supporting Actor. Nevertheless, Guinness - who hated the role, the script, and the film - convinced Lucas to kill off his character, and thus only contributed cameo appearances to the two sequels, The Empire Strikes Back (1980) and Return of the Jedi (1983). During this time, Guinness also portrayed George Smiley, the cynical spy created by novelist John Le Carre, in two acclaimed miniseries made for British television: Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy (1980) and Smiley's People (1982). He contributed an important supporting performance to David Lean's last film, an acclaimed adaptation of E.M. Forster's A Passage to India (1984). Guinness' fourth and final Dickens adaption was Christine Edzard's Little Dorrit (1988), a six-hour long painstakingly detailed epic. Guinness earned his fifth and final Oscar nomination for his portrayal of William Dorrit. In the 1990's only a few Guinness performances made it to the screen. He appeared in Steven Soderbergh's loose literary adaptation Kafka (1991), starring Jeremy Irons, and Charles Sturridge's A Foreign Field (1993), in which he starred opposite Leo McKern, John Randolph, Edward Herrmann, Geraldine Chaplin, Jeanne Moreau, and Lauren Bacall. Anthony Waller's 1994 thriller Mute Witness featured footage of Guinness that Waller had shot 9 years earlier while Guinness was waiting for a plane. Piers Haggard's poignant comedy-drama Eskimo Day (1996), made for British television and shown in this country on PBS as Interview Day, was Guinness' last screen performance. Sir Alec Guinness died of liver cancer on August 5, 2000, in Midhurst, Sussex, England.

In 1979, Guinness was awarded an Honorary Oscar for "advancing the art of screen acting through a host of memorable and distinguished performances." His trademark was, of course, versatility. Not just versatility in roles (British, Scottish, Japanese, Arabian, Russian, German, Italian, and Indian - he played them all), or versatility in performances (he switched with ease between lead roles, character roles, cameos, and documentaries), but also versatility in projects. Guinness worked in nearly every genre - social comedy, black comedy, spoof comedy, war comedy, family drama, war drama, Shakespeare, historical epic, literary saga, thriller, action, science fiction, and more - and he gave brilliant performances in films, stage productions, made-for-TV movies, and miniseries, not to mention the 1983 Star Wars video game made by Atari. He did not shy away from working with young directors like Lucas, Soderbergh, and Waller, and he raised the dignity level of any film he was in. Those who are interested in his career should read his autobiography, co-written with John Le Carre, My Name Escapes Me: Diary of a Retiring Actor (1997).

Films I've Seen Him In:

Leonard Maltin **** Films:

Leonard Maltin ***1/2 Films:

Leonard Maltin *** or "Above Average" Films:

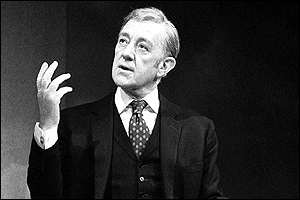

3. Ralph Richardson

Ralph David Richardson was born on December 19, 1902, on Tivoli Road in Cheltenham, Gloucestershire, England. Like Alec Guinness, John Gielgud, Laurence Olivier, and several of his other contemporaries, he started out performing classical theater at the Old Vic repertory in London. Like Guinness, he made his debut in a film directed by Victor Saville. Friday the Thirteenth (1933), a melodrama, begins with a bus crashing and one passenger dying. The film then proceeds in flashback, recounting the lives of 13 of the bus' passengers. At the end, it returns to the original bus crash and it is revealed "which of these chirpy, vivid characters has met a gruesome end" (IMDB user comment). He next played British Army officer Major Hugh "Bulldog" Drummond in Walter Summers' The Return of Bulldog Drummond (1934), a sequel to the 1929 film Bulldog Drummond, which earned Ronald Colman a Best Actor Oscar nomination for playing the title role. (He appeared the same year in a different role in Bulldog Jack (1934), a parody of the famous Sapper character.) In 1936, Richardson appeared in Things to Come (1936), an adaptation of an H.G. Wells novel scripted by Wells himself and directed by legendary set designer William Cameron Menzies. The same year, he supported Roland Young in another Wells adaptation, Lothar Mendes' The Man Who Could Work Miracles (1936). Richardson's first Hollywood film was King Vidor's acclaimed The Citadel (1938), produced by Saville and co-starring Robert Donat, Rosalind Russell, Rex Harrison, and actor-writer Emlyn Williams. Richardson continued to star in high-profile projects throughout the the '30s and '40s, such as Zoltan Korda's The Four Feathers (1939) and Peter Ustinov's School for Secrets (1946). By 1943, he was enough of a celebrity to star in Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger's propaganda short The Volunteer (1943), for which Steve Crook wrote the following plot summary: "After a masterful performance as Othello in a London theater Ralph Richardson is asked for an autograph by Fred, his dresser. A short while later, Fred has joined the Fleet Air Arm (Fly Navy) and has become a hero, rescuing a pilot from his burning plane. When Fred goes to Buckingham Palace it's Ralph's turn to ask for an autograph."

1948 saw Richardson in The Fallen Idol, which Carol Reed directed in between Odd Man Out (1947) and The Third Man (1949). The film was scripted by Graham Greene (who also wrote The Third Man), from his own story "The Basement Room," and it earned both Reed and Greene Oscar nominations. The following year, Richardson's performance in William Wyler's classic The Heiress (1949) earned him his first Oscar nomination, for Best Supporting Actor. Wyler's film, an adaptation of Henry James' classic novel Washington Square, starred Olivia de Havilland and Montgomery Clift, and earned the former a Best Actress Oscar for the lead role of Catherine Sloper. Richardson played her father, Dr. Austin Sloper, and he would continue to be cast in paternal roles for his entire career. Richardson reteamed with Reed for Outcast of the Islands (1952), from the Joseph Conrad novel, and then turned in his only directorial effort with Home at Seven (1952), a mystery-thriller in which he also starred. David Lean's Breaking the Sound Barrier (1952), scripted by noted playwright Terence Rattigan (The Browning Version, The Winslow Boy), earned Richardson Best Actor awards from the British Academy of Film and Television Arts, the National Board of Review, and the New York Film Critics Circle, but he was ignored at the Oscars. In 1954, Richardson appeared as Buckingham in Laurence Olivier's Richard III, opposite John Gielgud as Clarence and Olivier in the title role. (It was one of only three times that all three of them would appear in the same film.) Reed, Greene, and Richardson attempted to pull off a comedy with Our Man in Havana (1960), starring Alec Guinness as a vacuum-cleaner salesman who goes to work for British Intelligence. The same year, he appeared in Otto Preminger's 212-minute-long all-star epic Exodus (1960), scripted by former blacklistee Dalton Trumbo from the novel by Leon Uris.

Richardson showed off his true mastery of the craft of acting in Sidney Lumet's Long Day's Journey Into Night (1962). This 3-hour-long uncut production of Eugene O'Neill's autobiographical masterpiece of drama featured Richardson as James Tyrone, Sr., the patriarch of a family that is coming apart at the seams. Richardson's flawless delivery of a monologue in the fourth act revealed O'Neill's theme - the past will always affect the present - in a moment of blinding and profound insight. In 1965, Richardson turned in a compelling supporting performance as the title character's father-in-law in the David Lean epic Doctor Zhivago. He also narrated Orson Welles' fragmented Chimes at Midnight (1965), freely adapted by Welles from five Shakespeare plays, and considered by some to be a masterpiece. In 1966, Richardson essayed a supporting role in Basil Dearden and Eliot Elisofon's Khartoum, a historical epic starring Charlton Heston and Laurence Olivier. He also starred in The Wrong Box, a classic black comedy directed by Bryan Forbes and co-starring John Mills, Michael Caine, Dudley Moore, Peter Cook, Nanette Newman, and Peter Sellers. 1969 saw Richardson in two all-star epics based around World War II: Guy Hamilton's Battle of Britain and Richard Attenborough's directing debut, Oh! What a Lovely War!. (Both of these films featured Olivier and the latter also featured Gielgud; among Richardson's other co-stars in these two films were Michael Caine, Trevor Howard, Curt Jurgens, Ian McShane, Kenneth More, Christopher Plummer, Michael Redgrave, Robert Shaw, Susannah York, Michael Bates, Robert Flemyng, Barry Foster, Edward Fox, Anthony Nicholls, Corin Redgrave, Ian Holm, Juliet Mills, Cecil Parker, Penelope Allen, Gerald Sim, Dirk Bogarde, Jean-Pierre Cassel, John Clements, Jack Hawkins, Vanessa Redgrave, Maggie Smith, and John Mills.)

Richardson also did some work for television, starring in the comedy series "Blanding's Castle." In 1969, he played Sir Toby Belch in a TV version of Shakespeare's Twelfth Night (1969), which co-starred Alec Guinness as Malvolio. He was one of several giants of the English theater (Richard Attenborough, Cyril Cusack, Edith Evans, Pamela Franklin, Wendy Hiller, Ron Moody, Laurence Olivier, Michael Redgrave, Emlyn Williams, James Donald, Raymond Massey's daughter Anna, and Michael Redgrave's son Corin were among the others) who appeared in 1970 TV-movie adapted from Charles Dickens' David Copperfield and directed by Oscar-winner Delbert Mann (Marty [1955]). In 1972, Gielgud and Richardson transported their lead performances in David Storey's play Home to television, under the direction of Lindsay Anderson and co-starring Warren Clarke (A Clockwork Orange), Dandy Nichols, and Mona Washbourne (My Fair Lady). (Interestingly enough, all five cast members except for Gielgud would appear the following year in Anderson's satirical masterpiece, O Lucky Man!.) In Jack Smight's TV-movie Frankenstein: The True Story (1972), co-scripted by Christopher Isherwood, Richardson co-starred with James Mason, Leonard Whiting, David McCallum, John Gielgud, Agnes Moorehead, Margaret Leighton, Michael Wilding, Jane Seymour, and Michael Sarrazin as "The Creature." He also appeared on television in Mike Newell's The Man in the Iron Mask (1976), from the Dumas novel, Jack Gold's spy thriller Charlie Muffin (1979), and Alan Gibson's Witness for the Prosecution (1982), a remake of the 1957 Billy Wilder film based on an Agatha Christie play and short story. But his most impressive credit in this regard is probably Franco Zeffirelli's 6-hour-plus miniseries Jesus of Nazareth (1977), with a script by Anthony Burgess and an incredible cast including James Mason, Laurence Olivier, Anne Bancroft, Ernest Borgnine, Claudia Cardinale, Valentina Cortese, James Earl Jones, Stacy Keach, Ian McShane (The Last of Sheila), Donald Pleasance, Christopher Plummer, Anthony Quinn, Fernando Rey, Rod Steiger, Peter Ustinov, Michael York, Olivia Hussey, Cyril Cusack, Ian Holm, Ian Bannen, and Robert Powell (Tommy) in the title role.

Richardson's film work during the 1970's however, was in considerably less prestitigious projects. He co-starred in The Looking Glass War (1970), directed by and adapted from John Le Carre's novel by Frank Pierson, who would later win an Oscar for Dog Day Afternoon (1975). Leonard Maltin called Looking Glass a "good opportunity to study the leads' bone structure, since they never change facial expressions." Curtis Harrington's Who Slew Auntie Roo? (1971) was a bizarre and campy retelling of the Hansel and Gretel story, starring Shelley Winters. Tales From the Crypt (1972), a horror anthology from Britain's famed Hammer Studios which was based on the same E.C. comics as the later HBO series, was directed by legendary cinematographer Freddie Francis and featured Richardson as "The Crypt Keeper," a linking figure between the various segments. Lady Caroline Lamb (1972) would seem to have many things going for it, including a distinguished cast including Sarah Miles, Jon Finch, Richard Chamberlain, John Mills, Margaret Leighton, and Peter Bull, in addition to Olivier and Richardson in cameos. The direction was by highly respected dramatist Robert Bolt, directing his own screenplay, and even though this was his directing debut, his screenplays have been made into several acclaimed films, including David Lean's Lawrence of Arabia (1962), Doctor Zhivago (1965), and Ryan's Daughter (1970), Fred Zinnemann's A Man for All Seasons (1966) (from his own play), Roger Donaldson's The Bounty (1984), and Roland Joffe's The Mission (1986). As it turned out, Lady Caroline was Bolt's only bomb. Richardson, as always, was impressive in spite of the material, earning a BAFTA nomination for Best Supporting Actor. William Sterling's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1972), based on Lewis Carroll's beloved classic and featuring Richardson as The Caterpillar, "proves Americans don't have a monopoly on making bad children's musicals" (Leonard Maltin again). Richardson also slummed in Rollerball (1975), a futuristic sci-fi drama directed by Norman Jewison and starring James Caan. This decade wasn't all bad for Richardson, however. Lindsay Anderson's satirical surrealist musical epic O Lucky Man! (1973), one of the weirdest films I have ever seen with my own eyes, featured Richardson in two roles, the more prominent being a wealthy industrialist who makes an illegal arms deal with an African dictator (played by white actor Arthur Lowe in blackface) and then frames his assistant Mick Travis (Malcolm McDowell) for the crime. Mick, who was also the protagonist of Anderson's If.... (1968) and would later turn up in Britannia Hospital (1982), ends up in jail. After serving 5 years in prison, he is released broke and penniless. In desperation, he ends up wandering the streets of London, where a man carrying a placard (Jeremy Bulloch, who played Boba Fett in the Star Wars trilogy) suggests that he attend an open casting call. At the casting call, Mick is picked by a film director (Lindsey Anderson) to star in the director's new movie - O Lucky Man!. Weird, no?

Like every other actor profiled on this page, Richardson continued working well into senior citizenship. He lent his voice to the acclaimed animated film Watership Down (1978), from Richard Adams' best-selling fantasy novel. He portrayed the "Supreme Being" as a cameo in Terry Gilliam's Time Bandits (1981) and appeared the same year in another fantasy, Matthew Robbins' Dragonslayer. Wagner (1983), Tony Palmer's 5-hour-long miniseries (edited down from an original 9 hours on British television) about the legendary German composer, was notable mainly for featuring Gielgud, Richardson, and Olivier in the same scene as Pfistermeister, Pfordten, and Pfeufer (respectively), the three ministers of King Ludwig II of Bavaria (László Gálffi). Although the cast and big-budget production values provided something to watch, the film itself was was considered overlong and Richard Burton's performance in the title role was generally viewed as one of his weaker ones.

Richardson's last two films to be released were both minor ones - Peter Webb's Give My Regards to Broad Street (1984), starring Paul and Linda McCartney as characters based on themselves, and Invitation to the Wedding (1985), co-starring John Gielgud and directed by Oscar-winning composer Joseph Brooks ("You Light Up My Life"). But Richardson's best-remembered performance in the 1980's was given in a much more well-received film: Hugh Hudson's Greystoke: The Legend of Tarzan, Lord of the Apes. This film was a pet project of Oscar-winning screenwriter Robert Towne (Chinatown [1974]), who planned on directing it himself, but after Towne's directorial debut Personal Best (1982) went over budget, the studio punished him by taking Greystoke away from him. Disgusted by the final, re-written version of the film, Towne had his name removed from the credits and replaced with that of his sheepdog, P.H. Vazak. Vazak was nominated for an Oscar. So was Richardson, for the second time, for his supporting role as the Sixth Earl of Greystoke. This made him, at the time, the oldest actor to be nominated for an Oscar. Unfortunately, his death from a stroke on October 10, 1983, in the Marylebone section of London, came more than a year after the nomination was announced. Sir Ralph Richardson is interred at Highgate Cemetery in London, England.

Although Richardson is typically mentioned third among the Olivier-Gielgud-Richardson trio, he had the strongest screen presence of any of them, exuding authority and a reassuring paternalism in any role, even when he was a young man. It is no accident that many of Richardson's finest roles - The Heiress, Long Day's Journey, Doctor Zhivago, O Lucky Man!, Greystoke - were as the father or father figure of the protagonist. It is impossible to be bored when watching Richardson perform - his characters generate instant empathy (even the villains) and their actions are always compelling, no matter how unbelievable they may be. Although Richardson could be accused of hamming it up on occasion, he did so no more than Olivier or Gielgud, and never when the role did not call for it. Above all, Richardson, thanks to a lifetime of work and study, not to mention natural talent, was a complete and total master of the art of acting. His ability to convey nuances of character through the smallest actions represents a model that all thespians should try to emulate.

Films I've Seen Him In:

Leonard Maltin **** Films:

Leonard Maltin ***1/2 Films:

Leonard Maltin *** or "Above Average" Films:

Leonard Maltin **** Films: Leonard Maltin ***1/2 Films: Leonard Maltin *** or "Above Average" Films:

2. John Gielgud

Arthur John Gielgud was born on April 14, 1904, in London, England. His great-aunt was the celebrated stage actress Ellen Terry. He graduated from the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts and made his stage debut at 17 at the Old Vic, playing a herald in Shakespeare's Henry V. (He would continue to be associated with Shakespeare his entire career, as we shall see.) His film debut came with the 1924 silent film Who Is the Man?, and his best-remembered early film is Alfred Hitchcock's Secret Agent (1936), based on the novel Ashenden by W. Somerset Maugham. In 1930, he essayed his first stage Hamlet. In 1935, he gave the career of Laurence Olivier a boost by switching the roles of Romeo and Mercutio with him in a legendary production of Romeo and Juliet. Gielgud would work prolifically onstage throughout his entire life, but this essay will mainly concentrate on his film work.

In 1941, Gielgud narrated Michael Powell's propaganda short film An Airman's Letter to His Mother, a film which inspired the following IMDB user comment: "I wish more propaganda were this short." Although Gielgud was arguably this century's greatest Hamlet, he never played the role on film. However, in 1948 he did provide the voice of the Ghost of Hamlet's father as an uncredited favor to Laurence Olivier in the latter's Oscar-winning film version of the Shakespeare play. His next film role was also Shakespearean: he was Cassius to James Mason's Brutus in Joseph L. Mankiewicz's film of Julius Caesar (1953), produced by John Houseman. (Houseman would, much later in life, leave the producer's chair and win a Best Supporting Actor Oscar for James Bridges' The Paper Chase [1973].) In 1954, Gielgud played Clarence opposite Ralph Richardson's Buckingham and Laurence Olivier's Gloucester in the latter's production of Richard III. He also played the Chorus in Renato Castellani's little-seen Anglo-Italian film version of Romeo and Juliet. In 1956, he finally took on a non-Shakespearean role in showman Mike Todd's Oscar-winning production of Around the World in Eighty Days. This adaptation of the Jules Verne novel, directed by Michael Anderson, virtually defined spectacle in Hollywood for many years. Todd took advantage of his enormous budget by casting approximately 50 stars in cameo roles. (In addition to Gielgud, featured stars included Noel Coward, Charles Boyer, Ronald Colman, Peter Lorre, Red Skelton, Marlene Dietrich, John Carradine, Frank Sinatra, Buster Keaton, John Mills, Peter Lorre, and Ava Gardner.) In 1957, Gielgud played Warwick in Otto Preminger's adaptation of George Bernard Shaw's Saint Joan, scripted by noted novelist Graham Greene. He closed out the decade with John Frankheimer's TV-movie The Browning Version (1959), from Terence Rattigan's classic (and very depressing) one-act play.

Gielgud's film work continued to be sparse in the 1960's. He narrated Frédéric Rossif's acclaimed (and Oscar-nominated) documentary feature To Die in Madrid in 1963. In 1964, he transferred his acclaimed stage production of Hamlet to the screen. Gielgud did not star in this production, however; he only directed it, with the lead role going to Richard Burton. In addition to co-directing the film with Bill Colleran, Gielgud provided the voice of the Ghost once again - it must have been a piece of cake by this time. Gielgud's other accomplishment in the world of film in 1964 was his first Oscar nomination, for Peter Glenville's Becket. This excellent film, adapted by Edward Anhalt from Jean Anouilh's classic play and produced by Hal Wallis (Casablanca, The Maltese Falcon), detailed the friendship between King Henry II of England (Peter O'Toole) and his chancellor, Thomas a Becket (Richard Burton). When Becket is named archbishop of Canterbury, he finds God and decides that he must oppose the King's authority, even though he knows that he it will lead to his death. This famous and oft-dramatized (most notably by T.S. Eliot in his verse drama Murder in the Cathedral) historical event would seem to be nothing more than the inspiring story of one man's battle with his conscience, but Anouilh subverts our expectations by presenting a Henry who is racked with doubt about what he must do and a Becket who awaits his martyrdom with an almost masochistic fervor. Gielgud was featured in the supporting role of King Louis VII of France, who offers Becket shelter. He was Oscar-nominated for his efforts, as were O'Toole, Burton, Glenville, and Wallis, among the film's total of 12 Oscar nominations. Unfortunately, 1964 happened to be the year when the Academy showed its best judgement in history, nominating against Becket not just the eventual winner of the Best Picture Oscar, George Cukor's My Fair Lady, but also Stanley Kubrick's Dr. Strangelove, Robert Stevenson's Mary Poppins, and Michael Cacoyannis' Zorba the Greek. As a result of this and the My Fair Lady juggernaut that year, Becket's only Oscar went to Anhalt for Best Adapted Screenplay.

Gielgud continued to work consistently throughout the '60s, mostly in character roles. He played Henry IV in Orson Welles' final completed film, the loose Shakespearean adaptation which was entitled Chimes at Midnight (1965). The same year, he appeared in the Tony Richardson comedy The Loved One, scripted by Terry Southern (Dr. Strangelove, Easy Rider, The Magic Christian) and Christopher Isherwood (Berlin Stories, which later became Cabaret) from a novel by Evelyn Waugh (Scoop, Brideshead Revisited), and advertised as "The motion picture with something to offend everyone!" Also in 1965, Gielgud transferred to television (under the direction of George Rylands) his one-man Broadway show The Ages of Man, which consisted of the perfomance of excerpts from Shakespeare's plays. 1968 saw him in Tony Richardson's The Charge of the Light Brigade, a historical drama describing the events leading up to the battle immortalized by Tennyson in famous poem from which the movie takes its title. He also appeared the same year opposite Laurence Olivier, Anthony Quinn, Oskar Werner, David Janssen, Vittorio de Sica, and Leo McKern in Michael Anderson's The Shoes of the Fisherman, from Morris West's best-selling novel. Then there was David Greene's Sebastian (1968), about a British mathematician and cryptologist (Dirk Bogarde) who falls in love with one of his fellow code-breakers. This one was sold with the tagline: "We can't tell you what he does (it's an international secret) but he does it with 100 girls ... and he does it the best!" If you ever see this film (and I have no intention to), look for Donald Sutherland in a small role. Gielgud closed out the decade as one of many giants of British theater who contributed to Richard Attenborough's directing debut, Oh! What a Lovely War (1969).

In 1970, Gielgud played Old Hamlet's ghost for the third time onscreen, this time in Peter Wood's Emmy-winning made-for-TV production starring Richard Chamberlain. He starred in Julius Caesar again the same year (under the direction of Stuart Burge), this time in the title role opposite Charlton Heston as Antony and Jason Robards as Brutus. In Fielder Cook's Eagle in a Cage (1971), and again in Lindsay Anderson's Home (1972), from the David Storey play, Gielgud starred opposite Ralph Richardson. In 1972, Gielgud was featured in a supporting role in Jack Smight's TV-movie Frankenstein: The True Story, a revisionist take on the Mary Shelley classic which was co-scripted by Christopher Isherwood. He then appeared in 1973 in Charles Jarrott's ill-conceived musical remake of Frank Capra's classic 1937 film Lost Horizon, from the James Hilton novel, in the role of Chang, the same role that had earned character actor H.B. Warner a Best Supporting Actor Oscar nomination for the original. Unfortunately, the remake did not fare nearly as well. The following year saw Gielgud as part of an all-star cast in the acclaimed 390-minute long miniseries QB VII, directed by Tom Gries and scripted by Edward Anhalt from a novel by Leon Uris. Sidney Lumet's all-star Murder on the Orient Express, based on the classic Agatha Christie plot, gave Gielgud another notable role in 1974. In Joseph Losey's Galileo (1975), Gielgud played "The Old Cardinal." (In 1999, when the IMSA Drama Club staged the Bertold Brecht drama that the film was based on, Gielgud's role was played by Yisong Yue.)

1977 saw Gielgud in one of his best roles, and one of his few lead performances, in Alain Resnais' Providence. Providence was the English-language debut of one of cinema's greatest directors, and it earned Gielgud the New York Film Critics Circle Award for Best Actor. The same year, Gielgud appeared in Tony Richardson's follow-up to his Oscar-winning Tom Jones (1963), Joseph Andrews, also based on a novel by Henry Fielding. Gielgud returned to the classics for his next three roles, all in TV-movies released in 1978: the Chorus in Alvin Rakoff's production of Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet, John of Gaunt in David Giles' production of Shakespeare's King Richard the Second, and Gillenorman in Glenn Jordan's film of Victor Hugo's Les Miserables. In 1979, he essayed a supporting role in the updated Sherlock Holmes mystery Murder by Decree, starring Christopher Plummer as Holmes and James Mason as Watson. One of Gielgud's oddest projects was the notorious X-rated film Caligula (1980). Caligula, produced by Penthouse publisher Bob Guccione, was, according to Leonard Maltin, "Filmdom's first $15 million porno movie." That $15 million was enough to get not only Gielgud, but also Peter O'Toole, Helen Mirren, and Malcolm McDowell in the title role. (Of course, the pornographic scenes were not performed by the stars themselves.) Gielgud's other credits in 1980 include Otto Preminger's final film, The Human Factor, scripted by noted playwright Tom Stoppard (Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead, The Real Inspector Hound, and the screenplays for Terry Gilliam's Brazil [1985] and John Madden's Shakespeare in Love [1998]) from a novel by Graham Greene, and John G. Avildsen's The Formula, scripted by Oscar-nominee Steve Shagan (Avildsen's Save the Tiger [1973], Stuart Rosenberg's Voyage of the Damned [1976]) from his own novel. The latter film was generally panned, but it did feature one of Marlon Brando's rare post-Apocalypse Now performances.

Gielgud moved into some truly high-level pictures as the decade went on. He contributed a notable supporting turn to David Lynch's The Elephant Man (1980), a drama from the production company of Mel Brooks (!). The Elephant Man was nominated for the Best Picture Oscar, but it lost to Robert Redford's Ordinary People. Not fazed by this, Gielgud proceeded to contribute cameos to the next two Best Picture winners: Hugh Hudson's Chariots of Fire (1981), where he acted opposite noted British director Lindsay Anderson (If.... [1968], O Lucky Man! [1973], The Whales of August [1987]), and Richard Attenborough's masterpiece Gandhi (1982), where he joined an all-star cast of British, American, and Indian performers (including Edward Fox, John Mills, Trevor Howard, Candice Bergen, Martin Sheen, Om Puri, Amrish Puri, Roshan Seth, and a then-unknown Daniel Day-Lewis), in addition to newcomer Ben Kingsley in the title role. During the same time period, Gielgud also picked up his second Oscar nomination - and only Oscar - for Best Supporting Actor in Steve Gordon's Arthur (1981). The role of Dudley Moore's acid-tongued valet, Hobson, was turned down twice by Gielgud before he finally accepted it - although he later admitted that the role was "great fun." 1982 also Gielgud in another Hugo adaptation - Michael Tuchner's TV-movie The Hunchback of Notre Dame, which like the earlier Les Miserables, was scripted by John Gay (an Oscar-nominee for Delbert Mann's Separate Tables [1958]). In addition to appearing in all these films and the TV-movies The Seven Dials Mystery and Inside the Third Reich in 1982, Gielgud also appeared in that year's two most acclaimed miniseries: Giuliano Montaldo's Marco Polo and Michael Lindsay-Hogg and Charles Sturridge's Brideshead Revisited. The latter film, adapted from Evelyn Waugh's most famous novel, also featured an Emmy-winning performance by Gielgud's most famous rival and contemporary, Laurence Olivier. Oliver and Gielgud, as well as their other famed contemporary, Ralph Richardson, all appeared together in Tony Palmer's miniseries Wagner (1983), a movie worth seeing only for that notable fact. The same year, Gielgud starred opposite Gregory Peck and Christopher Plummer in Jerry London's made-for-television WWII thriller The Scarlet and the Black, based on an incredible true story.

Gielgud continued to appear in several films, TV movies, and miniseries throughout the 1980's. One of his more notable films during this period was Alan Bridges' The Shooting Party (1984), also starring James Mason. When director Don Taylor (Escape from the Planet of the Apes [1971]) staged Sophocles' Oedipus trilogy (Oedipus the King, Oedipus at Colonus, and Antigone) for television in 1984, Gielgud appeared as the blind prophet Teiresias in the first and third installments. Gielgud had the leading role in the minor comedy Time after Time (1985), and also appeared in Fred Schepisi's Plenty, from the play by David Hare. He turned up in Joseph Brooks' Invitation to the Wedding, which was Ralph Richardson's final film. (Richardson's character, incidentally, had the same name as Gielgud's character in Scandalous [1984].) In 1988, Gielgud played the role of Cardinal Wolsey in a TV adaptation of Robert Bolt's classic play A Man for All Seasons, directed by and starring Charlton Heston. (The play had earlier been made into a classic film by Fred Zinnemann in 1966, starring Paul Scofield, Orson Welles in what later became Gielgud's role, and Vanessa Redgrave, who starred in the Heston version, in a bit part.) The same year, Gielgud appeared in the sequel Arthur 2: On the Rocks. In 1989, he won a Golden Globe for his role in Dan Curtis' acclaimed miniseries War and Remembrance, based on the novel by Herman Wouk (The Caine Mutiny). Gielgud appeared in another acclaimed miniseries that year, Martyn Friend's Summer's Lease.

The 1990's saw Gielgud in what is most likely the oddest film he ever made (with the possible exception of Caligula): Peter Greenaway's Prospero's Books. This film was ostensibly based on Shakespeare's The Tempest, with Gielgud in the role of Prospero, but it was filtered through Greenaway's unique sensibility and contained what Leonard Maltin referred to as "a mind-boggling amount of nudity." Once of those getting nude was, believe it or not, Gielgud himself, performing his first nude scene at the age of 87. The film was packed with stunning visual imagery, but the play's impact (nearly all of the dialogue is spoken by Gielgud) was rather muted. Nevertheless, it is one the few films that Gielgud was completely allowed to dominate, and his presence is quite compelling. Gielgud also dominated Kenneth Branagh's Oscar-nominated short film Swan Song, based on a play by Anton Chekhov, in which he plays - what else? - an aging actor. He had a supporting role in John Erman's miniseries Scarlett (1994), based on the novel by Alexandra Ripley which was written as a sequel to Gone With the Wind. He also appeared in Jerry Zucker's First Knight (1995), an Arthurian drama from one of the directors of Airplane!. He then contributed the voice of King Arthur, uncredited, to Rob Cohen's fantasy Dragonheart (1996). (The voice of the dragon in that movie was Sean Connery, who portrayed King Arthur in First Knight.) Another fantasy made around the same time was the TV-movie Gulliver's Travels (1996), starring Ted Danson, which reunited Gielgud with Brideshead Revisited director Charles Sturridge. The same year, Gielgud was one of several prominent actors interviewed by Al Pacino for the latter's acclaimed documentary Looking for Richard, an examination of Shakespeare's Richard III. Gielgud then performed a cameo in Scott Hicks' Oscar-winning drama Shine (1996), based on the life of world-renowned pianist David Helfgott. He narrated The Discovery Channel's feature documentary The Leopard Son (1996), and appeared in Jane Campion's acclaimed adaptation of Henry James' classic novel Portrait of a Lady the same year. Not only that, but the astonshingly prolific Gielgud appeared (in a brief, non-speaking role) in yet another of 1996's most acclaimed films - Kenneth Branagh's gargantuan, 4-hour long adaptation of Hamlet. (Gielgud's character, Priam, is only mentioned as part of the Player King's monologue in the play, but Branagh decided to dramatize the monologue - about the burning of Troy during the Trojan War - in his film, adding to its everything-but-the-kitchen-sink quality.) Gielgud appeared in Steve Barron's acclaimed television movie Merlin (1998), but not as Merlin. He then provided the voice of Merlin for Frederik Du Chau's animated film Quest for Camelot. He then appeared briefly in Shekhar Kapur's Elizabeth, one of the best-reviewed films of 1998 and a Best Picture Oscar nominee. (Elizabeth marked the third time that Gielgud played a Pope; the other two were The Scarlet and the Black and The Shoes of the Fisherman.) Gielgud also appeared in David Yates' directing debut, The Tichborne Claimant (1998), and his final film was the British TV-movie Catastrophe (2000), directed by David Mamet and adapted from a play by Samuel Beckett. Sir John Gielgud passed away on May 21, 2000, in Wotton Underwood, Aylesbury, in Buckinghamshire, England.

Unquestionably one of the century's best actors, Gielgud, like James Mason, was probably best known for his ability to project nuances of emotion through his voice. (Indeed, he has been called "the world's greatest actor from the neck up.") His most important contribution to any film was dignity, and he played a succession of Lords, Kings, and Popes. Directors sought him out for high-class literary adaptations, which is why he has appeared in films based on the works of such authors as W. Somerset Maugham, Jules Verne, George Bernard Shaw, Terence Rattigan, Jean Anouilh, Evelyn Waugh, Lewis Carroll, David Storey, Mary Shelley, James Hilton, Agatha Christie, Bertold Brecht, Christopher Isherwood, David Mercer, Henry Fielding, Victor Hugo, James Joyce, Graham Greene, Alexandre Dumas fils, David Hare, Oscar Wilde, Robert Bolt, Herman Wouk, Anton Chekhov (whom he also portrayed in From Chekhov with Love [1968]), Leon Uris, Jonathan Swift, Henry James, Dante, and Sophocles, not to mention fifteen films based on the works of William Shakespeare. Granted, it was Gielgud's weakness that he could not convincingly play a character who was less than an aristocrat, but it was also his gift, and enabled him to grace well over a hundred films with his indelible presence. Not only that, but he was a viable force in the world of theater for the better portion of the 20th century, both as an actor and a director. His death (and the nearly contemporaneous passing of Sir Alec Guinness) truly marked the end of an era, and neither theater nor film will ever see his like again. Those interested in Gielgud's life and work might want to read his autobiographical books: Early Stages (1939), Stage Directions (1963), and Distinguished Company (1972).

Films I've Seen (or Heard) Him In: