Old Fort Sumner and The Death of Billy the Kid

Quien es? Quien es?

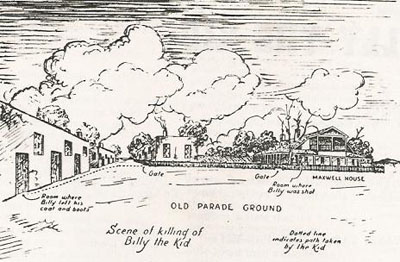

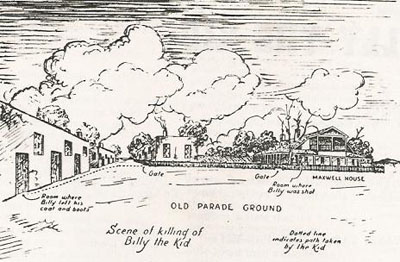

Sketch of the area where the shooting took place

It is very true to say that Fort Sumner is where Billy's life ended and his legend began. The Pecos river long ago claimed the site of Pete Maxwell's home and along with it went the tangible site of the Kid's death. Many eyewitness accounts exist regarding Billy's last moments. I have included deputy John W. Poe's account as well as numerous photos of Fort Sumner as it appears today to take you back in time to imagine how it must have been long ago on July 14, 1881 when the bright moon was shining and the hour was late. This is how Billy the Kid met his fate...

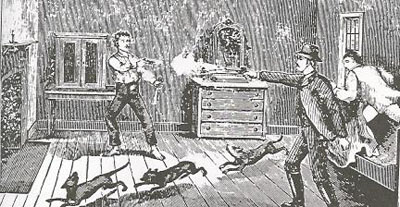

"Death of Billy the Kid"

by John W. Poe – A Deputy of Pat Garrett who was there when it happened

Article is taken from True West Magazine June 1962 and appears on this website courtesy of researcher Donna Tatting.

Editor’s Note: Billy the Kid has long inspired writers of Western fact (and fiction); his life and deeds, especially his death, interest a larger reading public than any other character of old western history. The account of his death has been so often distorted in the past few years that we think it’s time to bring back a first-hand report by John W. Poe, one of the deputies who was present at the shooting.

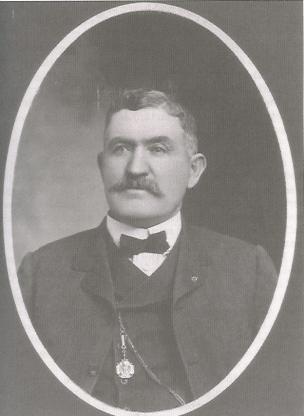

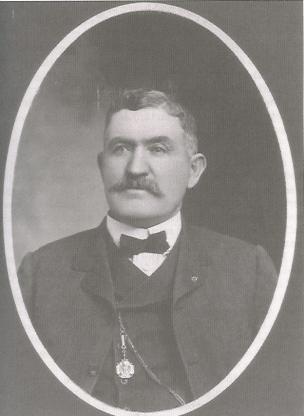

Deputy John W. Poe

Written in 1919, the account was published by Houghton Mifflin Company in 1933, complete with a comprehensive introduction by Maurice Garland Fulton, who resided in Lincoln County and became one the foremost experts on the controversial Kid. The introduction itself is a full-length article (and probably the longest introductory note ever to appear in any magazine) but after reading it, we felt the valuable and enlightening information it contains and the way it sets the stage for the article itself helps present the complete picture of the Kid’s death and events leading up to it. An authority on rare books tells us that the first edition of this one is very scarce and would be priced at $25 to $35 if available.

As an added bonus, we have included in this issue the story of the Maxwell Land Grant (page 26). Pete Maxwell who figures prominently in the following article, was the son of Lucien, the founder of the famous Maxwell Empire. We feel it apropos to present their story in conjunction with this feature. The spot where Billy breathed his last has a past fully as exciting and illstarred as the Kid himself. There is some speculation about where the final showdown would have occurred if Lucien Maxwell had still been alive-we give odds that it wouldn’t have been on the premises of the Emperor of the Cimarron !

Introduction by Maurice Garland Fulton

In a straightforward, plain and matter-of-fact style that adds sincerely to the recital, the late John W. Poe has recorded fully the circumstances of the death of Billy the Kid. His knowledge was first-hand, for he was one of the posse of three who, in the midsummer of 1881, very unexpectedly gave New Mexico and the Texas Panhandle everlasting riddance from that young scapegrace. Though the account was not written until nearly thirty-five years later, Mr. Poe’s undimmed memory and love of exact statement make the narrative fully as trustworthy as if written immediately after the event.

To one like myself, who saw Mr.Poe in the tranquility of 1922-23, the last year of his somewhat more than three-score and ten, there was little to suggest how largely the earlier half of this life had been filled with frontier hardships and dangers. The large, broad-shouldered physique together with an impressive gravity of demeanor, betokened that the man sitting at the president’s desk of the Citizen’s National Bank of Roswell, New Mexico, was a person of consequence, of great courage and determination, but did not give the passer-by and inkling of the roles he had played in ushering in law and order upon the raw and raucous southwestern frontier.

At the urge of an adventurous spirit, Mr. Poe had left his boyhood home on a Kentucky farm at seventeen and “gone west”. By the spring of 1871 he had penetrated into Kansas and was at the end of the Santa Fe Railroad, then slightly below Emporia, making a livelihood as a member of a construction crew. In 1872, he was a step farther into the unsettled parts, cutting timber and cross-ties on the Red River in Texas and the Indian Territory. In the spring of 1872, he pulled up stakes and traveled horseback 250 miles farther west to Fort Griffin.

There he handled a large wood contract for the garrison, but when this was completed, he became one of the crowd of buffalo hunters who were swarming over the plains of west Texas. In the four years (1874-1878) spent on the buffalo range, Mr. Poe made a reputation as one of the most successful hunters. His estimate that he had killed in the neighborhood of 20,000 buffalos with his own Sharps suggests both his skill and the lucrativeness of the business. When buffalo hunting ceased to be profitable, Mr. Poe entered upon several years of service as a law enforcement officer by accepting appointment as town marshal for Fort Griffin. In this capacity he served but one year – long enough to show his remarkable qualifications. He held a tight rein on that very tough town without killing a single person. Such a record won him higher recognition in 1879 when he became a deputy United States marshal.

He was stationed at Fort Elliot in the northeast corner of the Texas Panhandle. Cattle-stealing was rampant, but Mr. Poe curbed it so markedly that the Canadian River Cattleman’s Association selected him to look especially after their interests. How this employment led to a special mission into New Mexico, Mr .Poe relates at the beginning of his story. It will clarify matters somewhat, however, if we understand how Billy the Kid, the particular thorn in the flesh of the Panhandle cattlemen, had developed. The limits of an introduction forbid a full length account of William Bonney, alias Kid, alias William Antrim (to give the equipment of names under which he usually appears in legal documents) who has nowadays become simply Billy the Kid.

We cannot take space even to divest the first stages of his career of the legendizing that unquestionably envelops them; nor can we chronicle his part in the feud known as the Lincoln County War. Suffice it to say that when those disorders almost ceased in the summer of 1878, he had taken a prominent part in all the fighting and emerged with a reputation for coolness and shooting skill that was remarkable for one just out of his teens. But the hand of the law was clutching at him with two indictments – one for the killing of Sheriff William Brady, the other for the killing of his deputy, George Hindman, an outrageous deed which Billy the Kid and five or six others of his clique had accomplished on April 1, 1878.

The defeated remnant of the McSween faction, including Billy the Kid, withdrew to Fort Sumner, about ninety miles northeast of Lincoln. This old army establishment was now shorn of the prestige it had possessed ten years before, when the Bosque Redondo experiment was in progress seeking to impound and civilize the several thousand Navajos and Mescalero Apaches on the large reservation established on the Rio Pecos. The remains of the fort, including several square miles of land and a collection of buildings originally built by the United States Government for officer’s quarters, barracks, storehouses, stables and outhouses, had been purchased by Lucien B. Maxwell, of Maxwell Land Grant fame, who, after the loss of his vast estate on the Cimarron, had moved into the southern part of the Territory in an effort to recoup his fortune. In the course of time, Lucien B. Maxwell had been gathered to his fathers, but his son Pedro, more commonly called Pete, had succeeded to the headship of the family and the management of the sheep and cattle interests.

During the sojourn at Fort Sumner, Billy the Kid came into friendship with the Maxwells. The family seems to have been largely feminine and Billy the Kid’s personality and career had elements which made him attractive to that sex. Mrs. Maxwell, her daughters, and even the old Navajo servant-woman, Dulivena, grew attached to him and welcomed his presence whenever he was near Fort Sumner. It is still a moot question whether there developed between the young outlaw and one of the Maxwell daughters any more lively degree of interest than friendly acquaintance, but the present writer discounts heavily the echoes of the old gossip that may still be found in print. During the late summer and early fall of 1878, Lincoln County was in perhaps a worse state than when the Lincoln County War was in active progress. Instead of simply two warring factions, several bands of outlaws were roaming at will and harrying the land and its inhabitants. During all this pell-mell havoc and confusion, Billy the Kid began to emerge more and more as what, in present day parlance, would be called a “public enemy”.

He came back into Lincoln on several occasions, accompanied by some of his former McSween adherents, and they stole horses which they carried into the Panhandle to sell. On one such foray, the clerk at the Indian Agency, Bernstein, was killed, and while Billy the Kid was not actually responsible, yet it was generally ascribed to him and became the basis for issuing a United States warrant for him. In October the new governor, General Lew Wallace, came to New Mexico, clothed with plenipotentiary power to quiet the disorders. His program at first was all for mild measures. So far as old offenders were concerned, he would wipe the slate clean at once.

In November he issued an amnesty proclamation extending a general pardon to both factions for what had been done between February and November, 1878, but with the proviso that the terms of this offer might not be taken advantage of by “ any person in bar of conviction under indictment now found and returned for any such crimes and misdemeanors.” This limitation shut the door upon the Kid, under a double indictment for the killing of Brady and Hindman. He probably was not highly uncomfortable under the situation, for the officers of the law had virtually given over their attempts to arrest him. The fall term of court had been pretermitted, and this created a lapse of several months before there would be any activity on the part of those charged with arresting offenders or dispensing justice.

By February, 1878, the two original factions were ready to patch up a peace, and a conference was held in Lincoln. Billy the Kid, Tom O’Folliard and probably one of the Salazars representing the former McSween group, and Jesse Evans, Tom Campbell and James J. Dolan, representing the former Murphy-Dolan-Riley contingent, met and drew up terms of peace. But hardly was the ink dry on the document when the feud flared up again. As the conferees and several of their friends were going down the street of Lincoln celebrating the newly established era of amity and goodwill, they encountered Huston J. Chapman, a lawyer of the trouble-making type whom Mrs. McSween had secured to look after her interests.

For three or four months, Chapman had been a veritable gadfly both to the Dolan faction and to the military at Fort Stanton, especially Colonel Nathan A.M.Dudley, the commanding officer, who had come to the rescue of the Dolan crowd when they were hard pressed toward the end of the five-day fight at Lincoln in July. There was a clash of words between the Dolan group and Chapman, followed by two shots which left the lawyer’s body lifeless on the streets. If the old indictments mean anything, Campbell and Dolan were considered the principles in this killing, while Jesse Evans was an accessory.

Governor Wallace felt that the Chapman killing indicated a new and possibly more serious outbreak than before. He came upon the scene and took personal charge of the arrest of those responsible for the murder. One of the first his mind turned toward was Billy the Kid, and the letter to Colonel Hatch, then commanding the troops in New Mexico, was short and pointed:

“ I have just ascertained that the Kid is at a place called Las Tablas, a plazita up near Coghlin’s ranch. He has with him Thomas O’Folliard, and was going out of the Territory, but stopped there to rest his horses, saying he would stay a few days. He was at the house of one Salazar. “

“ You will oblige me by sending a detachment after the two men; and if they are caught, send them on to Fort Stanton for trial as accessories to the murder of Chapman. If the men are found to have left Las Tablas, I beg they may be pursued until caught. The details are commended to your good judgement.”

News of the Governor’s determination must have reached Billy the Kid, for, as the following letter to Governor Wallace written a few days later shows, he sought to bespeak for himself some sort of special dispensation:

“ I have heard that you will give one thousand ($) for my body, which as I can understand it means alive as a witness. I know it is as a witness against those that murdered Mr. Chapman. If it was so as I could appear at court, I could give the desired information, but I have indictments against me for things that happened in the Lincoln County War, and am afraid to give myself up because my enemies would kill me. The day Mr. Chapman was murdered, I was in Lincoln at the request of good citizens to meet Mr. J.J. Dolan, to meet as a friend so as to be able to lay aside our arms and go to work. I was present when Mr. Chapman was murdered and know who did it; and if it were not for those indictments, I would have made it clear before now. If it is in your power to annul those indictments, I hope you will do so, so as to give me a chance to explain. Please send me an answer telling me what you can do. You can send answer by bearer. I have no wish to fight any more; indeed, I have not raised an arm since your proclamation. As to my character I refer you to any of the citizens, for the majority of them are my friends and have been helping me all they could. I am called Kid Antrim, but Antrim is my stepfather’s name.

Waiting an answer, I remain, Your obedient servant W.H. Bonney”

Negotiations, both by letters and by interview, finally brought the Governor and the young outlaw into an understanding by which Billy the Kid was to undergo pseudo-arrest by Sheriff Kimbrell. The program was carried out, and Billy the Kid lodged under guard in the Patron Store building in Lincoln, pending the approaching session of the grand jury. When court convened about the middle of April, he was one of the witnesses whose testimony resulted in the indictment of Dolan, Campbell and Jesse Evans in connection with the Chapman killing. The Kid himself appeared in court and pleaded not guilty to the indictments against him for the Brady-Hindman killing. A change of venue to Dona Ana County was allowed, an arrangement which postponed his trial a month or two.

In the interval, however, Billy the Kid suffered a change of heart. Just before time to be taken over to La Mesilla for trial, he escaped and took refuge at Fort Sumner. Why he did this is hard to determine now. Possibly his faith weakened in regard to Governor Wallace’s ability to guarantee immunity, especially when the district judge, Warren Bristol, and the district attorney, William L. Rynderson, were implacably hostile to the McSween faction as well as politically opposed to Governor Wallace. Probably he also realized that if he did happen to “come clear” at the trial, he would face the enmity of the Dolan faction, embittered by his testimony before the grand jury. At any rate, he elected to burn his bridges behind him, and at once resumed his former habit of looking out for himself with the aid of his firearms.

He was at large in the vicinity of Fort Sumner for approximately a year-and-a-half. The question of a livelihood he met through monte-dealing and cattle-stealing. At the point of a pistol he had presented a claim to John S. Chisum for $500 back pay for services during the Lincoln county War, but the wily old cattle baron denied the claim and argued the Kid into lowering the revolver. The Kid, however, bestowed a parting threat that he would obtain the $500 in good measure from the Chisum herds, and he and his companions proceeded to make good the threat. Their cattle-stealing, however, soon passed the reprisal stage and became a definitely organized business. His gang grew until it included not only old Lincoln County associates like Charlie Bowdre and Tom O’Folliard, but also some even rougher men who had drifted into Fort Sumner, such as Dave Rudabaugh, Tom Pickett and Billy Wilson. Even the community itself at Fort Sumner probably furnished some recruits.

Fort Sumner was advantageously located as a base for such a business. About forty miles east, in the vicinity of Las Portales Lake, was an ideal hide-out where the booty might be concealed. It was easy to take horses out into the Panhandle and find a ready market at Tascosa and other settlements. It was equally easy to gather up on the return a bunch of cattle and carry them down through Fort Sumner and into Lincoln County, where Pat Coghlin at Tularosa had a depot ready and waiting for stolen cattle, with which to fulfill his government contracts. It was some such system that brought to a head the irritation of the Panhandle cattlemen. Frank Stewart, as special agent, came over into New Mexico with a posse in the early part of December, 1880, to retake cattle supposedly in the vicinity of Fort Sumner and in the hands of Billy the Kid’s gang. But prior to this, the toils had begun to close around the Kid. As sheriff-elect of Lincoln County, Pat Garrett had already begun his stern pursuit of the Kid and his followers.

The Kid aggravated the case against himself when in the latter part of November, 1880, he killed a popular resident of White Oaks, Jim Carlyle, in a fight at the Greathouse Ranch. Garrett carried the pursuit shortly afterward straight to Fort Sumner, in the vicinity of which the Kid’s gang was hiding. Frank Stewart and his men from the Canadian joined forces with Garrett’s posse. O’Folliard was ambushed; a little later, the Kid, Rudabaugh, Bowdre, Tom Pickett, and Billy Wilson were rounded up in a small hut a Stinking Springs. Bowdre was killed (the hat he was wearing causing him to be mistaken for the Kid). The remaining four decided to surrender. The Kid was taken to Santa Fe, where he was kept in jail until April, 1881, when he was taken down to La Mesilla for trial. This was quickly over; the Kid was sentenced by Judge Bristol to be hanged on May 13 at Lincoln. His dramatic escape is perhaps too well-known to be given here at any greater length than in the words Garrett wrote on the order of execution:

“ I certify that I rec’d the within named William Bonney alias Kid alias William Antrim into my custody on the 21st day of April, A.D. 1881. And I further certify that on April 28th the said Wm. Bonney alias Kid alias William Antrim, made his escape by killing his guard, J.W. Bell and Roberts Olinger in Lincoln Co., New Mexico.”

This Exhibition of derring-do put Billy the Kid more on a pedestal than before and attracted toward him the instinctive admiration of all lovers of “the art of daring”. Up to this point in his career, opinion had been divided. Was he a sneaks-by or a lad of mettle, a ruffian or a hero ? No definite answer seemed possible. But after this escape, popular imagination seized him for its darling and recognized in him more than a common killer and thief, more than a common leech on society. Even the Santa Fe New Mexican, always disparaging of the Kid, bestowed a grudging plaudit in the issue of May 4, 1881, a few days after the escape:

“ The above ( the account of Kid’s escape) is the record of as bold a deed as those versed in the annals of crime can recall. It surpasses anything of which the Kid had been guilty so fare, that his past offenses lose much of heinousness in comparison with it, and it effectively settles the question as to whether the Kid is a cowardly cutthroat or a thoroughly reckless and fearless man. Never before has he faced death boldly or run any great risk in the perpetration of his bloody deeds. Bob Olinger used to say that he was a cur, and that every man he had killed had been murdered in cold blood and without the slightest chance of defending himself. The Kid displayed no disposition to correct this until this last act of is when he taught Olinger by bitter experience that his theory was anything but correct.”

Bu from such an Apollo, the Kid’s life turns almost into the commonplace in its last scene. This young outlaw, with a Territorial reward of $500 upon his head, hides himself in the friendly camp of a Mexican sheepherder, and palters with the idea of leaving the country, at least for a time. One July night he seeks the sociability of a baile at the home of one of the leading Mexican ranch-owners in the vicinity of Fort Sumner. After the dance ends about eleven o’clock, he rides back to the sheep camp and then decides to go over to the Maxwell ranch. About midnight he reaches the room of one of the employees of the Maxwells living in the long row of adobe rooms to the south of the building in which the Maxwell family lived. After divesting himself of shoes and garments superfluous on a July night to a man seeking relaxation, he grows hungry and, learning that a freshly killed quarter of beef is hanging on the north porch of the Maxwell dwelling, he sallies forth, butcher-knife in hand, to cut for himself a piece of meat. His route takes him past two members of the posse at the end of the south porch, and at this point he seems to lose that genius for preserving his own life by means of his flaming pistol.

He moves on past the two strangers, who must have been revealed fully to him in the moonlight, and dodges into the doorway of Peter Maxwell’s bedroom, there to confront the pistol held by Pat Garrett and from it to receive the coup de grace. It was never easy to draw out Mr. Poe about the death of the Kid, but at Mrs. Poe’s urging, he finally wrote out the account and turned it over to her to keep against whatever time might be suitable for its publication. In the early part of 1919, Mr. Edward Seymour, of New York, a gentleman interested in the history of the West, feeling skeptical about certain information regarding the death of the Kid which had come to him, inquired of the late Charles Goodnight as to a reliable source of information. Mr. Goodnight referred him to Mr.Poe, making the comment that, “Whatever John Poe would furnish would be true.” As easiest way of giving Mr. Seymour the facts, Mr. Poe sent him a copy of the accounty Mrs. Poe was treasuring. This eventually reached Mr. E.A. Brininstool of Los Angeles who, perceiving its value, secured its publication in an English magazine, The Wide World, for December, 1919. Afterward, Mr. Brininstool published the account as a privately printed brochure, which in the course of time passed into the limbo of “out of print.”

The present volume give to this grim episode of the old Southwest that definitive and permanent form it richly merits, considering its importance as source material.

-Maurice Garland Fulton-

Death of Billy the Kid

During the winter of 1800-81, I was living in the Panhandle of Texas, where I had been serving as deputy U.S. Marshal and also as deputy sheriff. About the middle of that winter the cattlemen of the Panhandle, who had organized an association for the protection of their cattle interests known as the Canadian River Cattle Association, and of which Mr. Charles Goodnight was one of the leading spirits, submitted a proposition to me to enter their employ and , as their representative, to cooperate with the authorities of New Mexico with the view of suppressing and putting an end to the wholesale raiding and stealing of cattle which had been and was then carried on by Billy the Kid and his gang of desperadoes, of whom there were quite a number and of whom a great majority of the people in the localities where they were operating stood in fear and terror.

I was given practically unlimited authority to act for and represent the association in all matters affecting their interests in New Mexico, including authority to draw all funds necessary for apprehending and prosecuting thieves and rustlers, particularly those depredations of stock belonging to the Association, the only restriction being that I should proceed in a lawful manner. Pursuant to this agreement I went to White Oaks, Lincoln County, New Mexico in March, 1881. White Oaks was at that time a booming mining town and was a sort of rendezvous for tough characters generally, including the following of the Kid and their friends and sympathizers, of whom there were many. It was here that I first met Pat Garrett, who was at that time sheriff of Lincoln County.

After an interview with him, in which I explained the nature of my business in New Mexico, it was agreed that I should be commissioned as one of his deputies. This was done and we cooperated in every way possible to suppress crime in that region, particularly cattle rustling. It should be remembered that, at this particular time, the Kid was being held under guard at Lincoln, the county seat, under sentence of death for murder. But he had many sympathizers and followers still at large, stealing cattle, committing robberies and various other crimes. They were operating from the Panhandle through a great part of New Mexico and into Arizona. At our first meeting Garrett and I agreed that I should make a trip to Tombstone, Arizona, which was then in its palmist days as a mining camp. Some of the stolen cattle from the Panhandle had been driven there and I hoped to recover them. This program was carried out, and on the day of our second meeting in White Oaks, some time during the month of April, information came from Lincoln, some forty miles distant, that Billy the Kid had escaped from his guards, killing two of them, and was again at large.

This occurred only a few days before the time set for the Kid’s execution and naturally caused a great deal of excitement throughout the region. Garrett immediately started for Lincoln, while I remained on the lookout for the Kid at White Oaks for a time. Upon arriving at Lincoln on the night following the day of the escape, Garrett found that two of his deputies (Bob Olinger and a man named Bell) had been killed by the Kid. Partly by means of a cunning ruse and partly by reason of the carelessness of the deputies, Billy had broken into a room containing firearms, adjacent to where he was guarded, secured a six-shooter and immediately proceeded to add two more to is already long list of victims. Then he had compelled another man on the premises to secure a horse for him. He rode away leaving the people of the little town completely terrorized.

Garrett at once organized several posses and scoured the country in all directions for several days in a endeavor to recapture his man but, failing to find any trace of him, finally gave up the hunt in the full belief that the Kid had gone to Old Mexico. According to my recollection, this killing and escape occurred in the latter part of April, after which we were unable to learn anything whatever indicating the whereabouts of the Kid until the July following, notwithstanding the fact that we were constantly on the alert and made the most strenuous efforts to locate him.

During the interval between the time of the Kid’s escape and the time he was killed, I continued to make headquarters at White Oaks, during which time I scoured the country thoroughly, finding many stolen cattle and also the hides of stolen cattle which had been slaughtered. I had a number of arrests made, prosecutions instituted, etc., being assisted in all this by Sheriff Garrett, who cooperated with me in every way possible and whom I found to be a very brave and efficient officer. Some time in the early part of July, I was approached by a man in White Oaks (I had formerly known him in Texas). Although addicted to habits of dissipation, he was a man of good principles and had, on previous occasions, shown a desire to assist me in the work I had in hand.

This man told me a story in strict confidence-as he probably felt that his life depended on its being treated in that respect-the gist of which was that for want of a better place, he had for some time been occupying as sleeping quarters a vacant room in a certain livery stable, owned and operated by two men who were known to be friends of Billy the Kid. A short time previous, while in his sleeping quarters at night, he had overheard a conversation between the tow men which convince him that the Kid was yet in the country, making his headquarters at Fort Sumner, about 100 miles from White Oaks. The Kid, at two different times since his escape from Lincoln, had been in the vicinity of White Oaks and had met or communicated with the two men whose conversation my informant had overheard.

I was somewhat skeptical as to the correctness of this information, as it seemed almost unbelievable that the Kid, with a price on his head and under sentence of death, would still be lingering in the country. However, in view of the peculiar conditions then existing in the country and the fact that the Kid had many friends and sympathizers who looked upon him as a hero and who would probably shelter and protect him, I came to the conclusion that there was possibly truth in the story which had been told me and I immediately went to Lincoln where I laid the matter before the sheriff. The sheriff was much more skeptical than I was. He said he could not believe what the White Oaks man had told me; however, he finally said that, if I desired it, he would go to Roswell, where we would find one of his deputies named McKinney, and from there the three of us would go to Fort Sumner to unearth the Kid if he were there. This was agreed upon and the following day we went to Roswell where we found McKinney, who expressed his disbelief in the White Oaks story but who willingly joined us for the expedition to Fort Sumner, some eighty miles from Roswell.

After a few hours spent in Roswell arranging for the trip, we started about sundown, riding out of town in a different direction from that we intended to travel later, as it was absolutely necessary to keep the public in ignorance of our plans if anything was to be accomplished. After we were well out of the settlement, we changed our course and rode in the direction of Fort Sumner until about midnight. We stopped, picketed our horses, and slept on our saddle blankets for the remainder of the night. The next day we rode some fifty or fifty-five miles, halting late in the evening at a point in the sand hills five or six miles from Fort Sumner, where we again picketed our horses and slept until morning.

Since I was not known in Fort Sumner, while the other two men were, I rode into the place with the object of reconnoitering the ground and gathering information to aid us in our purpose, while the other two men remained our of sight in the sand hills. IN case of my failure to return to them before night, they were to meet me after darkness at a certain point agreed on some four miles out of Fort Sumner. I arrived in town about ten o’clock. Fort Sumner at that time had a population of only two or three hundred people, nearly all of whom were natives or Mexicans, there being not more than one or two dozen Americans in the place, a majority of whom were tough or undesirable characters in sympathy with the Kid. The remainder stood in terror of him. When I entered the town, I noticed that I was being watched from every side, and soon after I stopped and hitched my horse in front of a store (which had a saloon annex), a number of men gathered around and began to question me as to where I was from, where bound, etc. I answered with as plausible a yarn as I was able to give, telling them I was from White Oaks, where I had been engaged in mining, and was on my way to the Panhandle where I had formerly lived.

This story seemed to allay their suspicions to some extent and I was invited to join in a special drink at the saloon, which I did, being very careful that I absorbed but a very small portion of the liquor. This operation was repeated several times, as was the custom in those days, after which I went to a nearby restaurant for something to eat. After I had eaten a square meal, I loitered about the village for some three hours, chatting casually with the people I met in the hope of learning something definite as to whether or not the Kid was there or had recently been there, but was unable to learn anything. The people with whom I conversed were still suspicious of me, and it was plain that many of them were on the alert, expecting something to happen. In fact, there was a very tense situation in Fort Sumner that day, as the Kid was at that very time hiding in one of the natives’ houses there. If the object of my visit had become known, I should have stood no chance for my life whatever.

It was understood, when I left my companions in the morning, that in case of my being unable to learn any definite information in Fort Sumner, I was to go to the ranch of a Mr. Rudolph (an acquaintance and supposed friend of Garrett’s), which was located seven miles north of Fort Sumner at a place called Sunnyside. Accordingly, I started for Rudolph’s ranch about the middle of the afternoon, arriving there some time before night. I found Mr. Rudolph at home, presented the letter of introduction which Garrett had given me, and told him that I wished to stop overnight with him. After Reading the letter, he said that Garrett was a very good friend of his and that he would be very glad to furnish me with accommodations for the night. After supper was over, I engaged him in conversation, discussing the conditions in the country generally. After some little time I led up to the escape of Billy the Kid from Lincoln and remarked that I had heard a report that the Kid was hiding in or about Fort Sumner. Upon my making this remark, the old gentleman shoed plainly that he was getting nervous; he said he had heard that such a report was about, but did not believe it, as the Kid was, in his opinion, too shrewd to be caught lingering in that part of the country with a price upon his head, knowing that the officers of the law were diligently seeking him.

By this time I was pretty well convinced that Mr. Rudolph was naturally well-intentioned but, like so many others, was afraid of the Kid and, on account of this fear, was very reluctant to say anything whatever about him. I then told him plainly the object of our errand-that I had come to him with the express purpose of learning, if possible, where the Kid could be found. I told him we believed he was hiding in or near Fort Sumner and that Garrett expected that he (Rudolph) would be able to put us on the right trail. Upon my making this statement, Mr. Rudolph became more nervous and excited than ever, and reiterated his reasons for believing that the Kid was not in that part of the country. He showed plainly, so it seemed to me, that he was not only embarrassed but alarmed. The truth was, we afterward learned, he knew the Kid was hiding around Fort Sumner, but his dread of the Kid caused him to make misleading statements while withholding facts.

Darkness was now approaching. I told Mr. Rudolph that having had a rest and a good feed, I had changed my mind. Instead of stopping overnight with him, I would saddle up and ride during the cool of the evening to meet my companions. This I did much, I thought, to the relief of Rudolph. I rode directly to the point where I had agreed to meet my companions and strange to say, as I approached the point from one direction they came into view from the other, so we did not have to wait for each other. This proved to be a night of strange happenings with us, however, all the way through. We held a consultation as to what further course we should pursue. I had spent the day endeavoring to learn something definite of the whereabouts of the man we wanted, but without success. However, from the actions of the people I had met at Fort Sumner, together with Mr. Rudolph’s nervous and excited manner, I was more firmly convinced than ever that our man was in the vicinity.

Garrett seemed to have little confidence in our being able to accomplish the object of our trip but said he knew a certain house occupied by a woman at Fort Sumner which the Kid had formerly frequented. If the Kid were in or about Fort Sumner, he would most likely be found entering or leaving that house some time during the night. Garrett proposed that we go into a grove of trees near the town, conceal our horses, then station ourselves in the peach orchard at the rear of the house and keep watch on who might come or go. This course was agreed upon and we entered the peach orchard about nine o’clock that night, stationing ourselves in the shadows of the peach trees, for the moon was shining very brightly. We kept watch until some time after eleven o’clock, when Garrett stated that he believed we were on a cold trail. He had very little faith in our being able to accomplish anything when we started on the trip. He proposed that we leave the town without letting anyone know that we had been there in search of the Kid.

I then proposed that, before leaving, we should go to the residence of Peter Maxwell, a man I had never seen but who, by reason of his being a leading citizen and having large property interests, should, according to my reasoning, be glad to furnish such information as he might have to aid us in ridding the country of a man who was looked on as a scourge and curse by all law-abiding people. Garrett agreed to this and led us from the orchard by circuitous bypaths to Maxwell’s residence, a building used as officer’s quarters during the days when a garrison of troops had been maintained at the fort. The house was very long, one story adobe, standing flush with the street, with a porch on the south side – the direction from which we approached. The premises were all enclosed by a paling fence, one side of which ran parallel to and along the edge of the street up to and across the end of the porch to the corner of the building. When we arrived at the house, Garrett said to me, “This is Maxwell’s room in this corner. You fellows wait here while I go in and talk to him.” He stepped onto the porch and entered Maxwell’s room through the open door (left open on account of the extremely warm weather), while McKinney and I stopped outside. McKinney squatted on the outside of the fence, and I sat on the edge of the porch in the small open gateway leading from the street to the porch.

It should be mentioned here that up to this moment I had never seen Billy the Kid nor Maxwell, which fact, in view of the events transpiring immediately afterward, placed me at an extreme disadvantage. Probably not more than thirty seconds after Garrett had entered Maxwell’s room, my attention was attracted, from where I sat in the little gateway, to a man approaching me on the inside of the fence, some forty or fifty steps away. I observed that he was only partially dressed and was both bareheaded and barefooted (or, rather, had only socks on his feet) and it seemed to me that he was fastening his trousers as he came toward me at a very brisk walk. As Maxwell’s was the one place in Fort Sumner that I considered above suspicion; I was entirely off my guard. I thought the man approaching was either Maxwell or some guest of his. He came on until he was almost within arm’s-length of where I sat before he saw me, as I was partially concealed from his view by the post of the gate.

Upon seeing me, he covered me with his six-shooter as quick as lightening, sprang onto the porch, calling out in Spanish, “Quien es ?” At the same time he backed away from me toward the door which Garrett only a few seconds before had passed, repeating his query, “Who is it?” in Spanish several times. At this I stood up and advanced toward him, telling him not to be alarmed, that he should not be hurt, still without the least suspicion that his was the very man we were looking for. As I moved toward him trying to reassure him, he backed up into the doorway of Maxwell’s room, where he halted for a moment, his body concealed by the thick adobe wall at the side of the doorway. He put out his head and asked in Spanish for the fourth or fifth time who I was. I was within a few feet of him when he disappeared into the room.

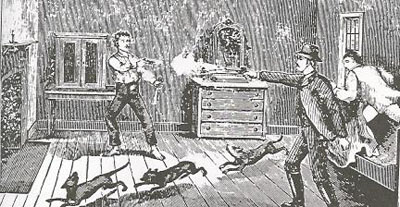

After this, and until after the shooting, I was unable to see what took place on account of the darkness of the room, but plainly heard what was said. An instant after the man had left the door, I heard a voice inquire in a sharp tone, “Pete, who are those fellows on the outside?” An instant later a shot was fired in the room, followed immediately by what everyone within hearing distance thought were two other shots. However, there were only two shots fired, the third report, as we learned afterward, being caused by the rebound of the second bullet, which had struck the adobe wall and rebounded against the headboard of the wooden bedstead. I heard a groan and one or two gasps from where I stood in the doorway, as if someone were dying in the room. An instant later, Garrett came out, brushing against me as he passed. He stood by me close to the wall at the side of the door and said to me, “That was the Kid that came in there onto me, and I think I have got him.” I said “Pat, the Kid would not come to this place; you shot the wrong man.”

Upon my saying this, Garrett seemed to be in doubt himself, but quickly spoke up and said, “I am sure that was him, for I know his voice too well to be mistaken.” This remark of Garrett’s relieved me of considerable apprehension, as I had felt almost certain that someone else had been killed. A moment after Garrett came out of the door, Pete Maxwell rushed squarely onto me in a frantic effort to get out of the room, and I certainly would have shot him but for Garrett’s striking my gun down, saying, “Don’t shoot Maxwell.” By this time I had begun to realize that we were in a place which was not above suspicion and as Garrett was so positive that the Kid was inside, I came to the conclusion that we were up against a case of “kill or be killed,” such as we had from the beginning realized would be the case whenever we came upon the Kid.

Pete Maxwell's grave in the Old Fort Sumner Cemetery

I have ever since felt grateful that I did not shoot Maxwell for, I learned afterward, he was at heart a well-meaning, inoffensive man, but very timid. We afterward discovered that the Kid had frequently been at this house after his escape from Lincoln, but Maxwell stood in such terror of him that he did not dare inform against him. By this time all was quiet in the room. The darkness was such that we were unable to see what the conditions were on the inside or what the result of the shooting had been. After some rather forceful persuasion, indeed, we induced Maxwell to procure a light. He finally brought an old-fashioned tallow candle from his mother’s room at the far end of the building. He placed the candle on the window sill from the outside.

This enabled us to get a view of the inside, where we saw a man lying stretched upon his back, dead, in the middle of the room, with a six-shooter lying at this right hand and a butcher knife at his left. Upon examining the body we found it to be that of Billy the Kid. Garrett’s first shot had penetrated his breast just above the heart, thus ending the career of a desperado who, while only about twenty-three years of age at the time of his death, had killed a greater number of men than any of the many desperadoes and “killers” I have known or heard of during the forty-five years I have been in the Southwest. Within a very short time after the shooting quite a number of the native people gathered around, some of them bewailing the death of their friend. Several women pleaded for permission to take charge of the body, which we allowed them to do. They carried it across the yard to a carpenter shop, where it was laid out on a workbench. The women placed lighted candles around it according to their ideas of properly conducting a “wake” for the dead.

All that occurred after the Kid came into view in the yard, up to the time be was killed, happened in much less time than it takes to tell it. Not more than thirty seconds intervened between the time I first saw him and the time he was shot. From Garrett’s statement of what took place in the room after he entered, it appears that he left his Winchester rifle standing by the side of the door, and approached the bed where Maxwell was sleeping, arousing him and sitting down on the edge of the bed near the head. A moment after he had taken this position for a talk with Maxwell, he heard voices on the porch and sat quietly listening, when a man appeared in the doorway and a moment later ran up to Maxwell’s bed, saying, “Pete, who are those fellows outside?” It being dark in the room, he had not seen Garrett sitting at the head of the bed. When he spoke to Maxwell, Garrett recognized his voice and made a move to draw his six-shooter. This movement attracted the Kid’s attention. Seeing that a man was sitting there, he instantly covered him with his gun, backed away, and demanded several times in Spanish to know who it was. Garrett make no reply and, without rising from his seat, fired, killing the desperado. This occurred about midnight on July 14, 1881. We spent the remainder of the night on the Maxwell premises, keeping constantly on our guard, as we expected attack by the friends of the dead man. Nothing of the kind occurred, however. The next morning we sent for a justice of the peace, who held a inquest over the body, the verdict of the jury being such as to justify the killing. Later on the same day, the body was buried in the old military burying ground at Fort Sumner.

There have been many wild and untrue stories of this affair, one of which was that we had in some way learned in advance that the Kid would come to Maxwell’s residence that night and had concealed ourselves there with the purpose of waylaying and killing him. Another was that we had cut off fingers and carried them away as trophies or souvenirs. In later years it has been said many times that the Kid was not dead at all but had been seen alive and well in various places. The actual facts, however, are exactly as stated herein. While no doubt, under the circumstances, we would have lain in wait for the Kid at the Maxwell premises if there had been the slightest reason for believing that he would come there, the fact that he did come was a complete surprise to us, absolutely unexpected and unlooked for as far as we three were concerned. The story that we cut off and carried fingers was even more absurd, as the thought of such a thing never entered our minds. We were not that kind of people.

The killing of the Kid created a great sensation throughout the Southwest and many of the law-abiding citizens of New Mexico and the Panhandle contributed substantially and liberally toward a reward for the officers whose work had finally rid the country of a man who was nothing less than a scourge. The death of the Kid had a very salutary effect in New Mexico and the Panhandle. Most of his followers left the country, for the time being at least, and a great many persons who had sympathized with him or been terrorized by him completely changed their attitude toward the enforcement of law. The events which occurred at Maxwell’s ranch on the night of that fourteenth of July to this day seem to me strange and mysterious, and the Kid was certainly a “killer” and was absolutely desperate. He had the drop first on me and then Garrett. Why did he not use

it ? Possibly because he thought he was in the house of his friends and had no suspicion that the officers of the law would ever come to that place searching for him.

From what we learned afterward, there was some reason for believing that we had been seen leaving the peach orchard by on of his friends, who ran to the house where he was stopping for the night, warning him of our presence. He had run half-dressed to Maxwell’s thinking that, by reason of the standing of the Maxwell family, he would not be sought there. However, this may be, it is still, in view of his character and the condition he was in, a mystery. I have been in many close places and through many trying experiences both before and after this occurrence, but never in one where I was so forcibly impressed with the idea that a Higher Power controls and rules the destinies of men. To me it seemed that what occurred in Fort Sumner that night had actually been foreordained.

The foregoing sketch or narrative was written at odd moments, taken from a very busy business life, upon the urgent request of oft-repeated solicitations of friends, and it is the first – and probably the last – attempt of the writer to record any of the facts related./

Historical Marker at the actual site of the Maxwell house and Billy's death site as it appears today. (Photo courtesy of Frederick Nolan)

Historical Marker at the actual site of the Maxwell house and Billy's death site as it appears today. (Photo courtesy of Frederick Nolan)

Historical Marker at the site of Billy the Kid's Death

Historical Marker at the site of Billy the Kid's Death

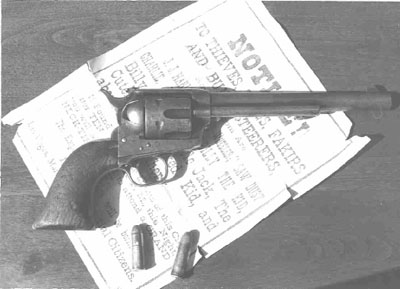

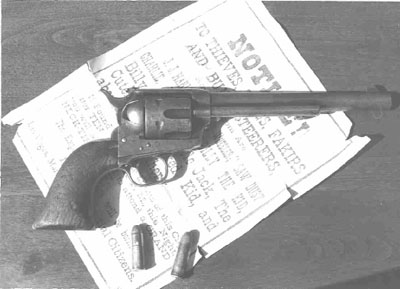

This 7 1/2 inch .44 Colt single action (Serial #55093) is the actual gun that Garrett used to kill Billy the Kid. Garrett obtained this gun from Billy Wilson after he was captured at Stinking Springs with the Kid. Jim Earle of College Station, TX now owns this gun as well as Bob Ollinger's shotgun.