WESTWORD -OCTOBER 11-17, 1989

TOMMY BOLIN WAS COLORADO'S BRIGHTEST MUSICAL HOPE UNTIL DRUGS BURNED HIM OUT.

BY GIL ASAKAWA

It's about 8:45 p.m. Friday. December 3, 1976. The Tommy Bolin Band is on stage at Miami's Jai-Alai Fronton, a sports arena, burning its way through an intense set as the opening act for superstar guitarist Jeff Beck This is the first night of the tour.

"This last song is from Private Eyes," announces Bolin, a Denver guitar player on the brink of stardom.

The band rips into a fifteen-minute version of "Post Toastee," a moody contemplation of the mid-Seventies rock scene's druggy excesses:

Don't let your mind Post Toastee, like a lot of my friends did.

Just keep me out of LA., things are crazy out there.

The people that I've been meeting, seems like I've got to beware.

Now I know I've been wrong, it seems like nothing is right.

I hope I get me some sleep tonight.

After two choruses, Bolin takes off on a screaming solo, then a series of rhythmic, echoing experiments. Halfway through the song, the house lights come on. Time's up, but Bolin's too involved in his six-string improvisations to stop now.

"Turn them lights down," he growls, launching into several minutes of unaccompanied guitar frenzy. The band joins in for the crashing finale. When Bolin finally leaves the stage, the audience is screaming for more.

Bolin's elated. After years of paying his dues, woodshedding and playing with other bands, this is the gig that will break his career wide-open. Private Eyes, his second solo album, has just been released; it showcases Bolin's unmistakable mix of melodic hard rock, cutting-edge jazz fusion and world-beat rhythms spun out with his distinctive guitar style. And Jeff Beck fans are the perfect audience. Before the concert, Bolin tells a friend the tour will be "the biggest thing I've ever done."

It's also the last thing he'll ever do. The first night of the tour is Tommy Bolin's final performance.

Ten hours after he walks off the stage, 25 year-old Thomas Richard Bolin is dead in a Miami motel room. He's suffocated from "acute multiple drug intoxication"--- alcohol, cocaine, barbiturates and heroin (in the form of morphine) overload his system.

Scattered around the room are bottles of health-food supplements. An autopsy uncovers the remains of ginseng in his stomach. Bolin had started thinking about cleaning up his act, but his interest in health was too little and came far too late. He'd ignored the warning in "Post Toastee" - the last song he ever played.

Like Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Jim Morrison and other late, great rock stars who overdosed on excess and success, Tommy Bolin left a legacy: his music. Local radio stations still play tracks from the records he made in the mid-Seventies with the James Gang and Deep Purple, as well as his two solo albums, Teaser and Private Eyes.

But much of Bolin's work has been hard to find or out-of-print altogether. Until now, that is. This week, Geffen Records will release Tommy Bolin: The Ultimate..., a multiple-disc retrospective.

The collection is a collaboration between two hardcore Bolin fans who thought his contributions to contemporary music shouldn't be forgotten --- a Montana musician named Will Dixon, a Bolin archivist working with the blessings of Tommy's family, and Tom Zutaut, a Geffen Records executive who supervised the project. The set spans Bolin's career, stretching as far back as Zephyr, the Boulder group that was Bolin's first brush with stardom.

After that came some of the Seventies' biggest bands. "The greatest players in the world wanted to play with Tommy," recalls Marty Wolf, a former Denver promoter and early Zephyr supporter who's now in Los Angeles managing heavy metal band Kingdom Come.

Thirteen years after his death, Bolin's colleagues still revere his work; Motley Crue just recorded "Teaser" for an upcoming anti-drug album featuring remakes of songs made famous by rockers who died of overdoses. With the Ultimate collection, Bolin's legacy can finally be enjoyed by music fans, not just musicians.

WITH HIS EXOTIC good looks - his father is of Scandinavian descent and his mother is Syrian - Bolin could have played himself in the Hollywood version of his life. The movie would have been a prototypical story of Seventies rock and roll of life in the fast lane until the road hits a dead end.

The scene running behind the opening credits of the Tommy Bolin story would be Tommy's first performance: Richard and Barbara Bolin dressing five-year old Tommy in an Elvis Presley costume- complete with blue suede shoes - for a talent show. Tommy didn't win the contest but that's where his obsession with rock and roll began. For years he carried a picture of Elvis in his wallet. Almost two decades later Bolin paid his respects to the King when he co-wrote the James Gang hit "Must Be Love" as a mock tribute to "All Shook Up."

Bolin's own rock-and-roll life began in earnest when he started playing guitar in various cover bands around his hometown of Sioux City, Iowa. But even as a teenager, Bolin wasn't satisfied by faithfully recreating the hits of the day. He discovered his destiny when he was sixteen years old, and kicked out of high school for refusing to cut his hair.

Within a few months, Bolin headed west to Denver, which had a reputation for being a hotbed of hipsters.

At first, he lived in seedy downtown apartments and panhandled in still-undeveloped Larimer Square. He also sought out other musicians. One was Jeff Cook, a seventeen year old songwriter and vocalist for a Denver band called American Standard. The two struck up a friendship that lasted through Bolin's career, and Cook co-wrote many of Bolin's best known songs. Today he works for Elektra Records in Atlanta, and still sings on records.

"American Standard was pretty amateurish," Cook recalls "but we were rehearsing in a downtown practice space somewhere on Curtis or Welton, and I heard someone knocking at the door. It was Tommy standing in the snow with his guitar. He said, 'Can I jam?' so we let him in. He plugged in and blew us away." Bolin joined on the spot, and American Standard became a regular opening band for concerts at the Family Dog, the club booked by young promoter Barry Fey.

Cook worked at the Folklore Center, a popular music store and hangout for folk and blues musicians. Bolin was soon a regular there, too. "He seemed to just love music," Cook says. "He was into Duke Ellington and John Coltrane, Albert King to B.B. King to Hendrix - it didn't matter what style or genre it was."

One day Bolin took a guitar off the wall and started playing the tricky time signatures of "Take 5," the jazz standard by pianist Dave Brubeck. "I about died, hearing him play that on guitar, when he was sixteen years old," Cook remembers. "You'd hear him play songs note for note one time, and then the rest of the time it would be different. I never, ever heard Tommy copy anybody."

While he was with American Standard, Bolin met the future members of Zephyr. His group and a blues band named Brown Sugar were both booked at an Aspen nightclub in '68. The driving force behind Brown Sugar was the husband-and-wife duo of bassist David Givens and singer and harp player Candy Givens.

Bolin and keyboard player John Faris soon left American Standard to start a more adventurous band. The Ethereal Zephyr, and Cook moved on to a blues band named Deep Rock. On New Year's Eve 1968, Ethereal Zephyr and Brown Sugar were both booked at a party put together by Marty Wolf and a partner, Kit Thomas. Suddenly, Bolin and the Givenses were making beautiful music together. With the addition of a drummer named Robbie Chamberlin, they joined forces as Zephyr in 1969.

ALTHOUGH ZEPHYR flopped commercially, it's still discussed in reverential terms around the Denver - Boulder scene. This was no ordinary blues band, Zephyr stretched the limits with its improvisational flair, quickly establishing a reputation for fiery performances and a hot young guitar player who split the stage - and the accolades - with a mercurial singer who had a voice like Janis Joplin with chops.

"People used to flip over us," says David Givens, who now lives in Hawaii. (Givens divorced Candy in the Seventies, although the two continued to work together in various groups, including different versions of Zephyr, until Candy's death in 1984. She drowned in a hot tub after drinking and taking Quaaludes.)

"People used to flip over us," says David Givens, who now lives in Hawaii. (Givens divorced Candy in the Seventies, although the two continued to work together in various groups, including different versions of Zephyr, until Candy's death in 1984. She drowned in a hot tub after drinking and taking Quaaludes.)

Wolf and Thomas, who helped organize Zephyr's first gigs, urged Fey to audition the band. Fey heard the band on a Sunday night in February 1969 at Shapes, an East Colfax nightclub. The next day, Fey convinced his West Coast competitor, Bill Graham, to book the band at the Avalon Ballroom in San Francisco and the Whiskey in Los Angeles. Soon Fey was acting as the band's unofficial manager, though he later relinquished control. "I was convinced I couldn't do the job because I was too inexperienced," he says now.

Zephyr's Los Angeles performance impressed several record labels and resulted in a record deal. Between stints in the studio, the band toured constantly, polishing its sound. The group played the Fillmore East (Bill Graham's New York club) and Fey's Denver Pop festival, where Bolin met Hendrix. Zephyr even played a festival in Boston that year: It came on second, after a new British group called Led Zeppelin.

Zephyr's debut album, Zephyr was released in 1969 on the short-lived Probe label. It wasn't an altogether happy experience: The rigors and monotony of studio work were frustrating, and led to heavy drug and alcohol abuse.

"We should have made a live record," Givens says. "None of us had been in a studio before, and the producer had no idea what to do with us." The group recorded all the songs in two days; after that the spontaneous tracks were thrown out and Probe kept demanding revisions.

"I remember Candy singing the same parts forty times, and Tommy doing those solos twenty or thirty times in a row," Givens says. It was then that the band got interested in drugs. "When we all lived together in a little house on Canyon Boulevard in Boulder, people used to think we were maniac drug-users, but we were mostly straight." Givens recalls. "Tommy used to take THC every now and then, but we played music all the time."

Tensions grew worse when Zephyr started working on its second album in 1970. Chamberlin had been replaced by Bobby Berge, a friend of Bolin's, and the new drummer didn't fit Givens says. "I didn't care for the rhythm stuff," he explains. "Bobby had a tendency to tighten up the beat so it was straight and hard, and it didn't swing."

Still, Going Back to Colorado sounded better than the first album, mostly because Candy Givens wasn't singing all over the melodic map, but also because Bolin had started developing his signature guitar style. According to Dave Brown, Bolin's friend and former guitar rival who had signed on as Zephyr's roadie, that's because someone had introduced Bolin to the echoplex, a piece of equipment that gave his guitar a spacey edge Bolin could control with a foot pedal.

Venturing ever further in search of new sounds, Bolin left Zephyr in the fall of '71, taking Berge with him. Zephyr broke up after one more album. Bolin was going strong with a new band, Energy. He'd always been a voracious fan of every kind of music, including the brand-new fusion of rock and jazz pioneered by Miles Davis in Bitches Brew and taken to dissonant extremes by John McLaughlin's Mahavishnu Orchestra. Released from the constraints of the twelve-bar blues, Bolin experimented with Energy.

Unfortunately, his rapid-fire riffs were a few years ahead of their time. "The stuff they were doing back then used to sound to me like a square wheel rolling down a corduroy road," Givens says. "Candy and I went to see Tommy one night. The room was full of young guys, no girls, sitting there watching him play guitar real loud." These guys didn't drink much and never worked up a sweat dancing; they were there to watch Bolin's six-string pyrotechnics.

Unfortunately, his rapid-fire riffs were a few years ahead of their time. "The stuff they were doing back then used to sound to me like a square wheel rolling down a corduroy road," Givens says. "Candy and I went to see Tommy one night. The room was full of young guys, no girls, sitting there watching him play guitar real loud." These guys didn't drink much and never worked up a sweat dancing; they were there to watch Bolin's six-string pyrotechnics.

Energy was invariably fired by every club except one: Tulagi, the tiny Boulder bar run by a renegade University of Colorado political science graduate student named Chuck Morris. Morris was a big Zephyr fan and booked the band in Tulagi every chance he got. He did the same for Energy, even though the group ruined his bar business. "Energy was practically my house band for a while," Morris says.

Bolin hung out at the club. One night when Morris got up enough nerve to perform a few country songs (he now manages acts like the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, Highway 101 and Lyle Lovett), Bolin offered to accompany him on the guitar. "This is so sick, I can't believe I can remember this," Morris says, "but he played that night with a cowboy hat on and he was such a whiz he played country licks like a pedal-steel guitar. I had never heard him do that before; for weeks after we called him 'Tennessee Tommy Bolin.'"

When the band ran out of local clubs, Bolin took Energy on the road. Keyboard player and singer Max Groenthal first met Bolin in Omaha in late '71, when Energy blew through town. "He had Jeff Cook with him in the band," recalls Groenthal (who now goes by Max Carl, as the lead singer for .38 Special). "I had a Traffic kind of band, jazz oriented, but not as heavy as Tommy's stuff." Groenthal was so impressed he later headed for Boulder and joined Energy.

As bandmembers came and went Bolin made important contacts. At a Boulder concert he introduced himself to flute player Jeremy Steig, whose records he'd admired. After hearing Bolin's music, Steig invited the young guitarist to New York for some studio sessions. There Bolin fell into the East Coast fusion scene, which included such notable musicians as keyboardist Jan Hammer and drummer Billy Cobham, both members of the of the Mahavishnu Orchestra. Cobham was so impressed he invited Bolin to play on his 1973 solo album, Spectrum.

At first, Bolin didn't believe it. "He said, "This guy calls and says this is Billy Cobham and I said yeah, yeah, sure this isn't Billy Cobham, and hung up," remembers Norma Jean Bell, Bolin's sax player.

There's no denying that Bolin's work on that record ranks as his best - his familiarity with every kind of music and his distinctive sound added soulfulness to the lightning-fast scales other hotshot guitarists could never match. "You'd see him pick up bits and pieces from everywhere, but when he recorded Stratus with Cobham, there was no reference point there," says Jeff Cook.

Bolin left Spectrum with a substantial reputation. "There were people who'd never heard anything about Zephyr or the James Gang, but they knew Spectrum," Dave Brown says.

As Bolin's sound evolved, so did his showmanship. Partly at the urging of his girlfriend, Karen Ulibarri, Bolin shed his shy demeanor and became more and more extroverted - on stage, at least. He draped feather boas over his shoulders; he and the other members of Energy dyed their hair psychedelic colors; he pierced his ears and began wearing the feather earrings that became his trademark. An early admirer of David Bowie's glitter-rock Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars album, Bolin embraced the exoticism of androgyny. On the cover of his first solo album, he looked like a woman.

"He was such a nice kid, he was always in a good mood," says Morris.

Groenthal's later memories aren't so pleasant "He was a gentle, sweet guy, but when it comes to drugs, compassion was forgotten for passion," he says.

In the early Seventies, though, Marty Wolf says Bolin was still the "happy little koala bear," before "the monster drug problem." Then, music was the problem.

"Energy played heavy metal jazz fusion-it was just too weird," says Cook, with pride. "People wanted to hear Rod Stewart covers; we looked weird and we sounded weird."

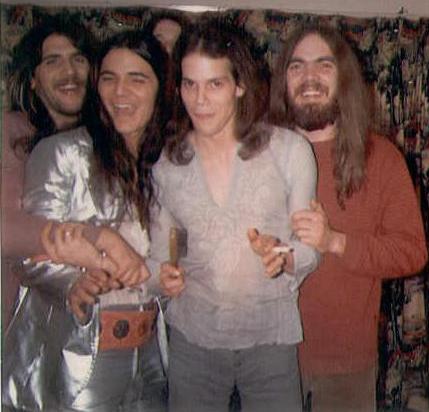

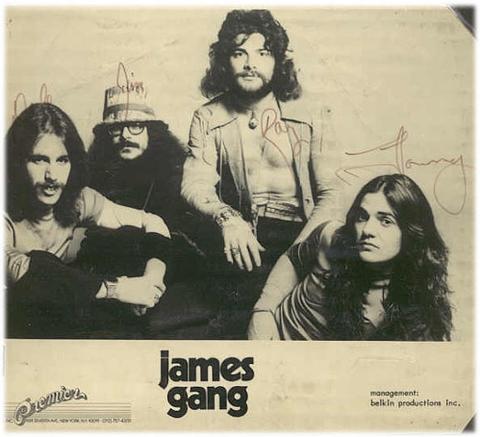

THEY RAN OUT OF ENERGY in 1973 when Bolin was offered a guitar-for-hire position he couldn't refuse. Joe Walsh had settled in Boulder after leaving the James Gang, a Cleveland-based group that had become a premier concert attraction (and was touted as an American version of the Who); he admired Bolin's playing on Spectrum but also knew the guitarist could rock.

When the James Gang asked Walsh if he knew of anyone who could replace Domenic Troiano, the man who'd stepped in for Walsh the year before, he recommended Bolin.

"The James Gang broadened his horizons and showed him how cosmopolitan the world was," Dave Brown says. "He learned that he could have fun then." Besides Ulibarri, Brown was Bolin's closest confidant. After being talked into becoming Zephyr's roadie and giving up his own band, Brown became Bolin's fulltime guitar technician and traveled with him for years. "We had made a deal," Brown says. "He said, 'You give up your career, and if I don't make it, I'll turn around and work for you. If I do make it, you'll never have to worry about anything.'"

"The James Gang broadened his horizons and showed him how cosmopolitan the world was," Dave Brown says. "He learned that he could have fun then." Besides Ulibarri, Brown was Bolin's closest confidant. After being talked into becoming Zephyr's roadie and giving up his own band, Brown became Bolin's fulltime guitar technician and traveled with him for years. "We had made a deal," Brown says. "He said, 'You give up your career, and if I don't make it, I'll turn around and work for you. If I do make it, you'll never have to worry about anything.'"

For the two albums he recorded with the James Gang, Bang and Miami, Bolin (with help from Jeff Cook) penned classic hard-rock songs like "Standing in the Rain." He also recorded his first lead vocal, on the beautiful ballad "Alexis."

Between James Gang engagements, Bolin returned to his old Boulder hangouts. But by then, Brown says, the standing joke in Boulder at the time was "Oh, he made it back this week?"

When he was in town, another acquaintance says, Bolin played quick gigs at local clubs for cocaine money.

"During a two year period, Tommy must have played two hundred times for me." Morris recalls.

Although he was making more money than he'd ever dreamed of, Bolin wasn't happy as the James Gang's lead guitarist. "I don't think he felt he had the freedom to do what he wanted, but it was a lot of money," says Cook. "It was just a great opportunity. The idea down the road was to put Energy back together."

"When we met Tommy, 'commercial' was a joke," remembers David Givens. "When he told me he was going to play with the James Gang, I laughed. We used to use them as an example of what we didn't want to be. But he had just made Spectrum and he was really proud of that. At that point there wasn't a whole lot going on, and he wanted the good life."

That good life turned sour soon enough. In August of '74, about the time Miami was released, Bolin quit the James Gang, saying he was unhappy with the band's musical direction. By then, Bolin had moved to Los Angeles to be closer to the heart of the music industry. Between bands, Bolin guested on another jazz-rock album [Mind Transplant], by composer/percussionist Alphonse Mouzon. He also signed with Fey for personal management. "He came to me and said, "I've been ripped off by everyone else, I want you to be my manager," Fey says. "He was amazing, he could have been huge. Superstars loved him, musicians loved him, the girls loved him-he just wanted to be a rock-and-roll star."

Fey got Bolin a deal to record a solo album with Nemperor, a new label run by a Fey acquaintance, attorney Nat Weiss. But then Bolin was offered another guitar-for-hire job, this time with the most popular hard-rock band in the world: Deep Purple.