Article by Dave Thompson

(Source: Goldmine: Oct. 9, 1998)

RITCHIE WHO?

by Dave Thompson

printed in Goldmine October 9, 1998

Originally transcribed by Darkhop [be sure to visit Darkhop's Gushpage], this article is provided here by Gord, and edited here for spelling, new paragraph breaks, etc. by Scott McIntosh

This article is an excellent read, and a timely accompaniment to the May, 2000 release, "Days May Come...", which is culled from the Come Taste The Band 1975 Rehearsal Tapes. This article includes tour dates and reviews, song reviews, personnel history, quotes gathered from a variety of sources, personal accounts, and details of Tommy’s final days. It offers us a unique insight to the Tommy Bolin era with Deep Purple.

LIFE WITHOUT RITCHIE

Ritchie Blackmore quit Deep Purple in April, 1975, although if you really dug deeply into the band's back pages, he'd actually been quitting for almost three years, ever since the night in San Antonio when keyboardist Jon Lord found himself walking down a hotel corridor with the guitarist, turned around to say something... "and suddenly he wasn't there. I turned around and he was leaning against a wall with tears running down his cheeks. I asked him if he felt all right, and he said, 'I don't know, I feel weird.' I asked him what he was crying for, and... he didn't even know he was crying. I started panicking, I said, 'Call the roadies! Get the manager! Hold the show!" In the end, the show went on. But the crack in Blackmore's eternal composure [?] masked more than even the guitarist realized at that time, a general discontent which nothing could cure, and which Deep Purple's continued existence only seemed to exacerbate.

From the outside looking in, many people were convinced he was going to quit the following year, following the completion of Who Do We Think We Are, and the departure of vocalist Ian Gillan. He stayed -- bassist Roger Glover went instead. A fresh bout of speculation surfaced in the aftermath of Burn, the band's first album with new members David Coverdale and Glenn Hughes; and another immediately after Stormbringer, an album which Blackmore was publicly condemning even before the reviews were cold.

But Blackmore outlived all the prophecies, then dropped his bombshell at the end of the band's spring, 1975, tour. He had a new band in place, its first album was recorded... "after weeks of rumor, accompanied by wild speculation in some parts of the press," the British music paper Sounds reported, "it was disclosed this week that... Ritchie Blackmore is to leave Deep Purple, his replacement being ex-James Gang member Tommy Bolin."

Four months later, in August, 1975, the band got down to making their first ever album without the man whose guitar lines, for many people, had come to epitomize Deep Purple. And there, Roger Glover insists, all comparisons with this year's Abandon go out the window. For not only is this actually the reformed Purple's second album without Blackmore (following on from 1996's Purpendicular, guitarist Steve Morse's debut with the group), it is also a far more confident band than that which struggled into the mid-1970s. Regrouping around founder members Ian Paice and Jon Lord, plus "classic" Purple mainstays Glover and Ian Gillan, Purple waved Blackmore goodbye with total equanimity.

"It was completely different; no feelings... no fear," Glover says. "No fear whatsoever. When Ritchie left in 1975... over the years we'd sunk into a certain state of mind regarding Ritchie: that without Ritchie there couldn't be a band. That was something that was ingrained in all of us, rightly or wrongly, and you know, you do the best you can at the time you're doing it, because you don't seem to have any choice. "But here we all were, suddenly presented with a choice, and for the band to have folded at that point I think would have given Ritchie some sort of moral victory... Ritchie leaves and Purple folds. And that made us extremely determined not to let that happen; in fact we were a bomb ready to blow up... no, that's a bad analogy. We were a flower ready to bloom. Again.

And that's exactly what happened. "I think we were all so determined to make it work, and the way to make it work is not to try and make it successful, but to shrug your shoulders and say 'hey! whatever happens, happens."

And what happened was, two albums which Glover rates amongst Deep Purple's happiest ever, and a band which he insists is enjoying life together more than ever. How different, indeed, it is to the scenario which faced the band in 1975.

Jon Lord and Ian Paice both admit that when Blackmore left the band 23 years ago, they came very close to following him -- Blackmore never made any secret of his admiration for Paice, and as far back as 1973, the pair were jamming with Thin Lizzy bassist Phil Lynott, tentatively testing the waters for what could have been an awesome collaboration. It didn't happen, but now that Blackmore really had departed, sometimes they wished it had.

The departures of Gillan and Glover, after all, left them both with an unrelenting hatred for the audition process, the truckloads of demo tapes which they felt duty-bound to play through as they searched for a new singer and a new bass player. The idea of having to repeat the process in search of a guitarist was a living nightmare. But for the members who emerged from that original audition process, David Coverdale and Glenn Hughes, Blackmore's departure offered them the chance of a lifetime. Both had joined Deep Purple with only the vaguest notions of what was expected from them on the creative front, but already they had wrested control of the band away from the classically underlined, guitar-heavy epics of fond memory, and into almost revolutionary pastures of soulful daring-do. Ritchie Blackmore even called them a funk band, and it didn't matter that he was scarcely being complimentary when he did so.

Hughes himself was secretly satisfied. The opportunity to bring in a new guitarist, one whose heart was not so deeply rooted in the hard rock which Blackmore loved, was one he could not... would not... pass up.

The mid-1970s were the era of the guitar hero, but they were also an era in which such creatures seemed in very short supply. The Rolling Stones in early 1974, Mott The Hoopel a few months later... every time another vacancy came up, it seemed the same old list of eligible young ax slingers just went around and around. Jeff Beck, Mick Ronson, Rory Gallagher, Harvey Mandel... the list was short, sweet and star-studded, and as Deep Purple weighed up their options, they found themselves returning to the same handful of names again and again. Beck, of course, was a pipe dream, and nobody ever really believed that he could be persuaded to give up a career of solo dilettantism to wheel out "Smoke on the Water" every night for the foreseeable future.

But then David Coverdale suggested Tommy Bolin, and he did sound like a possibility... a talented rock guitarist to be sure, but further reaching than that, a musician versed in blues, funk, soul, you name it. Neither was he averse to stepping into a superstar's shoes. 24 years old, he'd just spent a year as Joe Walsh's replacement in the James Gang, and indisputably made that band's sound his own.

The true mark of his talent, however, was his involvement with Billy Cobham's epic of jazz-rock fusion, 1973s Spectrum album, and it was this which really clinched Purple's invitation, as Bolin himself admitted in a November, 1975 interview with 7HO radio in Melbourne, Australia. It was roadie Nick Bell who made the initial approach, Bolin revealed.

"David like, uh, heard me on Cobham albums and stuff, you know, and James Gang albums, and they were looking all over the East Coast: New York, and Boston, and yadda-yadda you know, I guess; and I live like two minutes from him, in Malibu, California. It was ridiculous, so..." Somewhat more coherently, Purple manager Rob Cooksey continued, "[Tommy's] name was the first that was brought up, but we didn't even know how to get in touch with him. We brought Clem Clempson from Humble Pie out to L.A. and tried him out for three or four nights, just jamming. He was working out really well, but he just didn't have the magic. So we decided to call it a day, and Clem went home, and we were really despondent. We got Tommy's number off some guy in the Rainbow in L.A. and it turned out he was living three miles down the road from us in Malibu."

Bolin wasn't initially certain about the offer. "[But Nick] called up and they just said, 'Do you wanna... you know, jam a bit', and I said yeah. You know, I wasn't that enthused about being in an English band. Because English bands tend to be a bit sterile a lot, I mean... every time they play, it's the same jokes, the same, you know it really is, [and] it gets to a point of being really bland, and I just didn't wanna, you know the way I play, I didn't wanna be a part of that."

He was eventually lured down to the band's practice space, however, and admitted that what he heard blew him away. He had never actually listened to Deep Purple in the past -- "I'd heard 'Smoke on the Water,' and I'd heard 'Highway Star,'" he said. Now he discovered that although Deep Purple may have been an English band, "they're a very Americanized English band; I mean, they grew up with the same roots as I grew up with, which really amazed me, playing like R&B stuff, Sam and Dave, Motown, you know, yadda-yadda."

If what the guitarist saw of Deep Purple that evening was a revelation to him, Jon Lord remembers the band being equally taken aback by Bolin -- and that was before they even heard him play. "He walked in, thin as a rake, his hair colored green, yellow and blue with feathers in it. Slinking along beside him was this stunning Hawaiian girl in a crochet dress with nothing on underneath."

And once he plugged in, blasting through four Marshall 100-watt stacks, they were sold. Even as he played, Bolin could hear Coverdale excitedly asking the others, "what did I tell you? What did I tell you?" The guitarist was invited to join on the spot. "He came down and it was instant magic," Cooksey confirmed. "From the first couple of bars we could tell immediately he was the guy. He liked us, we liked him, and we just took it from there."

Bolin continued, "The whole band... they asked, you know, 'would you like to, you know'... so then I started thinking, 'well okay...' I started presenting tunes to them, some of my songs, and things went really well; I mean, they accepted the majority of things that I thought would be... I didn't know, like, what vein to really go into. Those two tunes were actually the only ones I really knew of, you know? So..."

Bolin and his new bandmates spent the best part of the next three weeks simply jamming, feeling one another out and making sure that the chemistry worked before the press was informed of his arrival. It was a needless precaution: long before that period was up, Bolin and Coverdale had put almost half an album's worth of songs together, and now the only things that needed to be sorted were the business arrangements.

"At the moment Tommy's pursuing two entirely different careers," Rob Cooksey confirmed to Circus. "But one compliments the other. His coming into Deep Purple has certainly given him an 18-month to 2-year start on his solo career. He's ambitious and together and he's got youth on his side." In fact, his career outside of the band was the furthest thing from Bolin's mind in the first few weeks of his life with Deep Purple. Even before the band's call came, Bolin had booked himself into the studio to begin work on a solo album, Teaser; now, he was frantically trying to juggle contracts and commitments so that his new bandmates could join him on his record, before he joined them on theirs!

In the event, only Glenn Hughes was free to stop by, contributing backing vocals to one track, while Jon Lord was also spotted hanging out at the studio. For the most part, Bolin relied on older friends -- Jan Hammer, Bobby Berge, Stanley Sheldon, and Genesis drummer Phil Collins, and over the next month or so, Teaser was completed.

Bolin rejoined Deep Purple in July, slipping into the band's schedule with remarkable ease, instinctively linking with Glenn Hughes on the funkier end of things, and bringing a new vision to what had, as Blackmore's interest in Purple declined, become an increasingly stale side of the band.

"I wrote that at one of the rehearsals," Bolin revealed. "I just thought... 'oh man, you know they would probably enjoy'... you know, because I was starting to feel them out, and they were starting to feel me out, and it was like... a give-and-take situation, even musically. And... I just kind of presented [them] with all the tunes, mostly; I just presented... the music, a riff, or whatever. And I would construct the tune around it, and David would take it from there, and do the lyrics, or Glenn would do the lyrics, or you know, whatever."

Another number, "Lady Luck," had been knocking around Bolin's live set for the past four years, requiring only that final fine-tuning which Coverdale was able to offer. "It's good to play... in a new environment with new people, because it brings a certain life out of a tune," Bolin explained, continuing, "Writing with David is great. And also with Glenn. I'll probably be writing a lot more with Glenn on the next one."

"Owed to 'G'," meantime, originally evolved from a jam between Bolin and Lord, which in turn developed into the album's showpiece ballad, "This Time Around." The whole piece had a Gershwin-esque air to it, and Bolin submitted the "G" of the title was, in fact, George Gershwin. "Jon and Glenn were going to call their half [of the song] 'Gersh,' and I was going to call my half 'Win,'" Bolin recalled later.

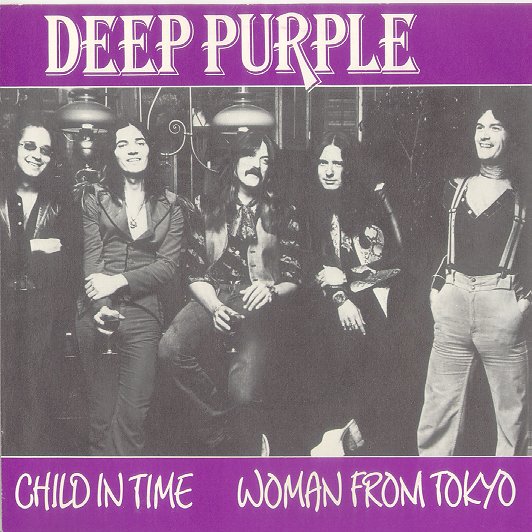

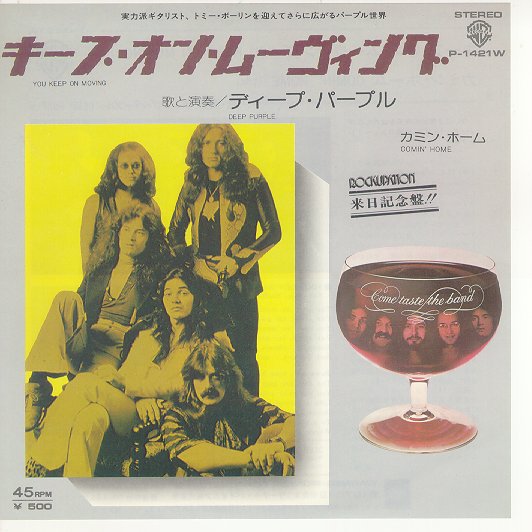

The album's standout track, however, was the sinewy six minutes of "You Keep On Moving," and while Bolin was not actually credited with the songwriting, he was also able to wrap some delightful leads around it. It was, everyone involved was aware, a song which would completely alienate the majority of "Child In Time"-loving oldtime Purple fans. But it was also uniquely capable of introducing the band to a whole new crowd of people, listeners who maybe hadn't hit puberty midway through "Smoke on the Water," and didn't share Ritchie Blackmore's distaste for funky music. Indeed, if any song on what became the Come Taste The Band album indicated the true depth of promise encapsulated within the so-called "Mark Four" line-up, that was it, and deservedly it was lifted off the album as a single... albeit one which barely sold, even to the faithful.

The album's standout track, however, was the sinewy six minutes of "You Keep On Moving," and while Bolin was not actually credited with the songwriting, he was also able to wrap some delightful leads around it. It was, everyone involved was aware, a song which would completely alienate the majority of "Child In Time"-loving oldtime Purple fans. But it was also uniquely capable of introducing the band to a whole new crowd of people, listeners who maybe hadn't hit puberty midway through "Smoke on the Water," and didn't share Ritchie Blackmore's distaste for funky music. Indeed, if any song on what became the Come Taste The Band album indicated the true depth of promise encapsulated within the so-called "Mark Four" line-up, that was it, and deservedly it was lifted off the album as a single... albeit one which barely sold, even to the faithful.

It was not only in the studio, however, that Bolin seemed set to usher Deep Purple to new heights of musical creativity and development. Visually, too, he promised to bring an element of flash into a band whose fans had grown way too accustomed to having an introvert Man In Black on stage-left. And of course, this was one of the leading topics of conversation when Bolin was interviewed by Melbourne's 7HO radio, barely ten days into his first tour with the band.

Bolin seemed surprised to hear it. "The only time I saw [Blackmore] was the California Jam thing, where... it was a TV thing, there was like a huge flamethrower thing or something like that, and somebody loaded it too much, and it about burnt Ritchie's britches off! And you could tell it on TV, you know, it was like, uh..." --words apparently failed Bolin there, but what it was like was, a mega-dose of adrenaline which not only stung Blackmore into manic action, it kept him there for the rest of the show. And if Bolin thought that was the standard he had to follow, then it's no wonder he seemed so hyperactive onstage. It was one mighty surprise for the fans, though.

Bolin made his live debut as a member of Deep Purple on November 2 in Honolulu, then spent the next week relaxing by the hotel pool. Talking over a year later to his hometown Sioux City radio station KMNS, he laughed, "[Honolulu] was the first Purple concert. But it was kind of, I got my smallpox shot. It was like, aw, eeeet, the smallpox shot and the TDT also. My week in Hawaii was watching everybody swim." From there, the band traveled to New Zealand for two shows, on November 13 and 17, before touching down in Australia for six nights: three in Sydney, two in Melbourne and one in Auckland.

From Australia, the band hit Indonesia for two shows in Jakarta in early December, then moved on to that most faithful of Purple strongholds, Japan, for four shows which made a mockery of Western critics' claims that the band's appeal had diminished in the years since the epochal Machine Head album.

Gigs in Nagoya, Osaka and Fukuoka (five tracks from which later appeared on the ultra-rare Deep Purple Rises Over Japan concert video) led up to a riotous homecoming at Tokyo's Budokan, and just as they had four years previous, when the Made In Japan double album set new standards for in-concert recordings, the band's record company made sure the event was preserved for posterity. They shouldn't have bothered.

Despite the inclusion of both the Stormbringer favorite "Solder Of Fortune," and the (for obvious reasons) crowd-pleasing "Woman From Tokyo" in the set, the show which eventually emerged as the Last Concert In Japan live album was not one of Deep Purple's greatest. Few people around the band would have denied that as a guitarist, Tommy Bolin was a genius; unfortunately, that genius came at a price -- one which was collected every evening by the drug dealers who seemed to be in permanent attendance around him.

As the tour progressed, Bolin's chemical unpredictability would play havoc with the band's performance, but the Tokyo show -- preserved both on the heavily edited official live album, and the audience recording which emerged as the Get It While It Tastes bootleg -- surely marked a nadir of sorts. Before the show, a bad fix damaged Bolin's left arm, weakening it to such an extent that he probably shouldn't have even been attempting to play -- let alone recording a showpiece album in front of his band's most fanatical supporters. Filtering down from Bolin's obvious incapacitation, the entire performance is ragged, stilted and dull, and the band felt nothing but relief when, just one show (in Hong Kong) later, they were freed for their Christmas vacations.

As the tour progressed, Bolin's chemical unpredictability would play havoc with the band's performance, but the Tokyo show -- preserved both on the heavily edited official live album, and the audience recording which emerged as the Get It While It Tastes bootleg -- surely marked a nadir of sorts. Before the show, a bad fix damaged Bolin's left arm, weakening it to such an extent that he probably shouldn't have even been attempting to play -- let alone recording a showpiece album in front of his band's most fanatical supporters. Filtering down from Bolin's obvious incapacitation, the entire performance is ragged, stilted and dull, and the band felt nothing but relief when, just one show (in Hong Kong) later, they were freed for their Christmas vacations.

The tour resumed on January 14, 1976, in Fort Bragg, North Carolina. It was to be a fraught reunion. Bolin's suddenly-revealed capacity for screwing up had haunted his bandmates throughout their break, yet if ever the group needed to present a united front to the world, it was now.

Commercially, Come Taste The Band was dying on its feet. Days before the tour kicked off, Deep Purple's twelfth album had finally struggled to its American chart peak of #43, the band's lowest ranking since 1970s In Rock had scaled the now-unimaginably ignominious depths of #143. Back then, though, they had expected little better. In a land which knew them for nothing more challenging than a Top Five cover of "Hush," of course Deep Purple's sudden embracing of the hard rocking blues of "Bloodsucker," "Flight of the Rat" and "Living Wreck" caught people unawares.

It did not take America long to catch up with them, though: Fireball, in 1971, made it to #32; Machine Head hit #7; and "Smoke on the Water" banged them all the way back up the singles chart, not only landing the band their first gold disc, but giving rock a national anthem it still hasn't grown tired of -- even if its makers have. "Do you want to know the new name of the band?" Roger Glover confided during Deep Purple's summer, 1998, American tour. "The new name of the band is, Deep Purple -- Oh Yes, 'Smoke on the Water,' I Went To College With That."

The band toured tirelessly in those days, criss-crossing America until there could not have been a rock fan in the land who hadn't seen them play. And they knew exactly what those fans wanted from them. "The average age of our audience is about 19," Ritchie Blackmore once said, "and you must accept that they really don't understand music that much. They're trying to understand it, but... if they were really hip, they wouldn't like us. They wouldn't like Led Zeppelin, they wouldn't like anybody. They'd be into Yehudi Menuhin."

So Deep Purple played to that audience's expectations, at the same time as trying to extend and expand them, conjuring vast, sonic epics out of the basic soup of riff-laden blues, then taking even their own expectations to new limits.

"I could never understand our success," Roger Glover laughed. "I could never understand why so many people bought our records, because they were so full of flaws! But I came to reassess the whole thing, mainly through listening to live bootlegs, and I realized what a dangerous band we were, and how exciting it was not to know what was going to happen next. We walked a very thin line between chaos and order, and that was the magic, veering off and suddenly the solo's in E when it should be... 'hey, what's happening here?' That's the magic," and that's what they gave their fans. And if they elevated even half of those people's awareness to a point where they could differentiate between good music and bad, then they knew they'd done their job.

The critics rarely liked Deep Purple, of course, preferring to describe the band as a leviathan riff machine, pounding out its monotonal message to a lumpen mass whose IQ was so frighteningly low that it needed to be watered daily. But the band members themselves knew better. And they knew they were better.

"America is so vast that I think people there buy records mainly by bands they've seen, and I should imagine that they've seen Grand Funk all over America," Blackmore once remarked. "But at the same time, I've never met one person who liked Grand Funk." [Me either. --DH]

The partial disintegration which shook Deep Purple in 1973 barely registered on their following. [Hah!] Maybe David Coverdale didn't have the vocal range of Ian Gillan, and certainly Glenn Hughes didn't have the melodic touch of Roger Glover. But Burn, the new line-up's debut, still had its share of Purple classics... the title track, for starters, and "Mistreated," of course, so when Stormbringer didn't live up to even the most generous expectations, the fans were willing to hang on and hope.

Come Taste The Band shattered those hopes. Without ever landing a really scathing review; without really serving up any substandard songs... it wasn't that it was a bad album, it just didn't sound like Deep Purple anymore. And with only two members of the "classic" line-up still around, Jon Lord and Ian Paice, who could be surprised at that?

The January, 1976, American tour, then, was the band's chance to redeem themselves in their audience's eyes; to prove the true pedigree of their new songs, and to line them up alongside the old... new songs like "Drifter," riding on a riff which was second cousin to "Mistreated"; like the Zeppelinesque "Love Child," with its classic Purple chorus built around an old James Gang riff which Bolin had hung onto; like "This Time Around," the ghostly, stately ballad with a touch of Queen around its phrasing. Some minor fine-tuning (and the insertion of Bolin's "Homeward Strut" in place of "You Keep On Moving") notwithstanding, the live set itself would be left relatively intact.

It was the band's internal dynamics which needed attention. Requesting anonymity not out of fear or malice, but because he claims to still really love the musicians involved, one former Deep Purple retainer explains, "the problem wasn't so much that Tommy was into drugs, it was that the rest of the group weren't, which meant he was off in his own world a lot of the time, and the others didn't understand where he was coming from." In other words, the drugs didn't affect the quality of Bolin's performance, so much as its nature and intent.

"Tommy was like Hendrix in a lot of ways, in that he could be completely out of his head, and he'd still leave your jaw on the floor. The difference was, Hendrix only had two other musicians with him, and they knew their job was to follow him, and make sure what he was playing always had a firm base beneath it. Deep Purple didn't work like that. You couldn't just go soloing off at a moment's notice, because Jon would be playing his part, or Ian or Glenn or David, and Tommy just didn't get that."

Yet Bolin was not alone in his chemical peregrinations, as Glenn Hughes later admitted to Metal CD magazine. As far back as his first (Burn era) American tour with Deep Purple, he acknowledged, "I started using coke, and it started getting heavy. I was a millionaire at 21, coked out of my mind, with my own limo, Rolls Royces everywhere. I could have shot somebody and got away with it. I never did a bad show, but I was a little bit erratic to be around.

It was just that Bolin was even more erratic. If some nights (Tokyo included) resulted in musical chaos, however, others caught the band attaining heights which even the so-called classic Mark II machine of Gillan, Blackmore and co. would have been hard pressed to reach. One of these came in Miami on February 9, a night which was surreptitiously, but fortuitously, recorded for eventual release as a bootleg. From the opening of "Burn" and "Lady Luck," through a thunderously claustrophobic "Smoke on the Water," and onto Bolin's "Owed to G" solo showcase, the band was firing on every cylinder they could find, even pulling in a rare airing for the new album's "Dealer," a Bolin/Coverdale song whose very title put the rest of the band on red alert.

Three weeks later, in Long Beach, the band was in fine form once again, this time for the benefit of the King Biscuit Flower Hour team. An earlier show on the tour, in Springfield on January 26, had been recorded but never broadcast: competent though the performance was, and remarkable for the one-night-only inclusion of the playfully "Speed King"-ish "Comin' Home" in the set, it lacked excitement and punch, and was marred by poor sound throughout. The tapes were shelved, and the Biscuit people were invited to try again later. And this time their efforts paid off.

But the group was smoking that night, the individual pieces slotting together so firmly that even today, seasoned Purple people pull out the tapes as an indication of precisely how much this incarnation of the band was capable of. Stepping out of the shadows of Deep Purple's history; out from under the imponderable weight of all that they had accomplished in the past, that night in Long Beach returned Deep Purple to the very top of the game... which makes the events of the next three weeks appear all the more inexplicable, all the more tragic.

The American tour closed on March 4 in Denver, Col.; seven days later, the band would be back on the road in Britain, for a sold-out mini-tour which opened in Jon Lord's hometown of Leicester, headed south for two nights in London, moved north across the border to Glasgow, then came to a close in Liverpool on March 15. From there, they'd move on to Germany, with the rest of Europe scheduled for the summer.

Unfortunately, they would never make it that far.

The musicians were bored. Worse than that, they were miserable. And while they all thought that they were keeping their feelings to themselves, all they were really doing was dragging one another down.

Glenn Hughes, looking back from two decades distance, admitted that almost from the beginning, he found Deep Purple to be "rather boring on stage. It wasn't really challenging for me. I didn't enjoy the squared-sounding heavy metal stuff they did, a la 'Space Truckin.' I felt like a B act in a B movie. It was nice singing with David Coverdale, and the Burn record worked very well. But this big live thing of five guys doing solos was the most boring shit. We got away with it, but I didn't like it."

Ian Paice, too, was finding the whole situation intolerable, albeit for different reasons. He told Modern Drummer "what should have happened was, when Ritchie said he wanted to quit, we should have said, 'let's just stop and look at this.' He, Jon and I should have sat down and said, 'look, if it's because of Glenn Hughes and David Coverdale and what they're doing, then let's change the band again, or let's just take two years off. We'll all do what we want, come back in two years' time and look at it again.' That's what we should have done, because if we had, it would have continued through... and we'd have had a lot of fun all along. We would have done a tour every two years, made a record and still had a nice social circle.

"But when Ritchie left, we were a bit silly. We were determined to carry on and we brought Tommy Bolin in. As good a player as he was in the studio, he was hopeless on stage. When he got on a big stage, he just seemed to freeze up. Instead of playing a solo, he'd end up shouting at the audience and arguing with them" -- usually about Ritchie Blackmore. Bolin told Circus magazine, "if someone yells 'Where's Blackmore?' at one of our concerts, I'll just do what I did when people yelled 'Where's Joe Walsh?' at me while I was with the James Gang. I'll have cards printed up with his address and throw them out to the audience."

The band could deal with that side of Bolin's personality. They didn't like it, but they understood it. Besides, time would soon sort it out, and once the audience got accustomed to seeing him there, the Blackmore brigade would soon shut up. What they couldn't handle was his drug intake: "His personal problems," as Ian Paice so delicately put it. "That's when it became too much." Jon Lord agreed. The band just wasn't any fun anymore, and if he was honest... really honest... about it, it hadn't been any fun since Gillan and Glover departed. "Of course, I know we carried on for a few years after with David and Glenn and then Tommy, but... I don't know, it was never quite the same."

But it was David Coverdale who finally gave vent to the emotions which everyone else was busily bottling up. The last British date, at the Liverpool Empire, had been dreadful -- uninspired and uninspiring, the band wasn't even going through its paces anymore. Bolin had pretty much given up playing guitar, and a fractious crowd only added to their suffering. Simon Robinson, author of the sleeve notes to the Tommy Bolin boxed set, insists, "I'll never forget their final show in Liverpool, where left alone to do a solo spot before an expectant crowd, Tommy just dried up. As he floundered on the huge stage, a lone fan dashed down one of the aisles screaming encouragement -- 'Come on Tommy, you teaser!' The P.A. blew his cries away and the over-zealous bouncers bundled him back to his seat. The cries for Blackmore grew in strength."

Bolin's failure that night was the final straw. Walking offstage in tears, Coverdale turned to Paice and Lord, and completely broke down: "I just can't take this any more." They could do nothing more than agree with him. Hughes and Bolin were never officially informed of Deep Purple's demise. As far as they were concerned, the tour was over -- the German gigs had been canceled due to band members' exhaustion, but the group would be honoring them later, when they reconvened after a few months off. Then it would be time to begin work on another record, and the pair were still looking forward to writing more together.

It would be another four months, July 19, 1976, before the pair learned they were, in fact, out of a job, when the band's management broke the news of the break-up. The members scattered to the winds. Ian Paice and Jon Lord were already rehearsing an eponymous trio with Tony Ashton; David Coverdale was planning a solo career. Glenn Hughes returned to the band he'd left when Purple first came calling, Trapeze; and Tommy Bolin went home to America, to form a new band of his own. He seemed unbowed by his experiences. Discussing Deep Purple on his hometown radio station on November 26, 1976, he shrugged, "They were together what, like eight, nine years, so... they're all doing like solo albums. Jon and Ian have a group; uh, David is attempting to do a solo album; and Glenn said he did a double album which I've yet to see, but I wish him all the luck in the world."

The Tommy Bolin Band hit the US concert circuit within weeks of his return from England, touring with Steve Marriott and Robin Trower. From there, it was into the studio to record the follow-up to Teaser, Private Eyes. He played some sessions with Moxy; he reunited with Billy Cobham on the proposed successor to the groundbreaking Spectrum; and once the Purple split was confirmed, he linked up with Glenn Hughes to discuss forming a new band together. Amidst rehearsals for Bolin's own next tours (back-to-back outings with Jeff Beck and Fleetwood Mac), the pair jammed together and there seemed a real possibility that something would come of their efforts.

Bolin flew to Miami in late November, in readiness for the first night of the Beck tour, and on December 3, 1976, he returned to the Jai Alai Fronton Hall, scene of a less than stunning Purple gig earlier in the year, for a performance which this time left everybody speechless. It was the last show he would ever play.

Following the concert, and a photo call with Beck, Bolin and his girlfriend returned to their Miami Beach hotel, the Newport. Bolin had been doing drugs all evening, but when he passed out in the early hours of the morning, nobody wanted to call a doctor. Everybody in his entourage had seen this happen before; doubtless they would see it again, and besides that, the thought of the adverse publicity which would emerge if such events ever got out was enough to keep everybody away from the telephone.

Instead, they simply bundled him into bed, watched while his breathing normalized and his color started returning, then they left him to sleep it off. The following morning dawned, and Bolin looked dreadful. Finally, around 8 a.m., his girlfriend called for an ambulance -- Bolin died from what the coroner's report called "multiple drug intoxication," shortly before it arrived.

Almost quarter of a century on, Bolin's death remains a dreadful coda to the bitter demise of the original Deep Purple. Of course it is unlikely that he would have played any part in the band's 1984 reunion (although who is to say he might not have been called upon to replace Blackmore again, when the guitarist quit in 1995), but Come Taste The Band at least paints a promising picture of what Bolin and Glenn Hughes might have accomplished had their own planned reunion taken place.

Indeed, history has been surprisingly kind to Come Taste The Band itself -- certainly kinder than the band's fans were at the time of its release, while the King Biscuit release proves that no matter what problems Deep Purple Mark IV were dragging around with them, when everything clicked on stage, they were easily the equal of most past incarnations. Roger Glover, watching Purple's collapse from the sidelines, admits as much when he reflects, "When you do something in a band, it's only afterwards, when it's a failure, that you can come up with the reasons for that. But at the time you're doing it, you don't know what's going to work, and what isn't going to work. The Tommy Bolin version of the band -- who knows? It might have been huge. And if it had been, how different would the stories have been then? It's all in the lap of the Gods." And it's up to the Gods what they do with it.

END

BACK to Tommy Bolin Picture Discography

BACK to Tommy Bolin Picture Discography