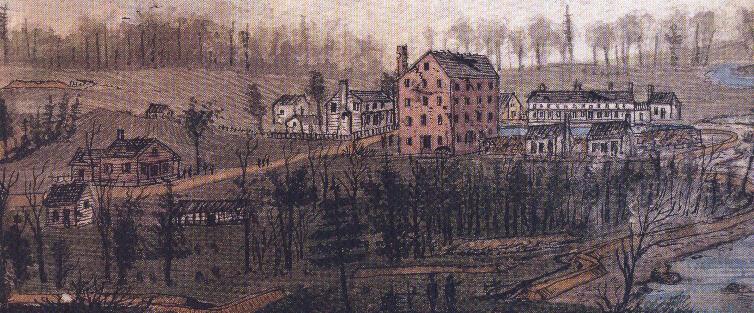

Kelly’s Ford, from Images of the Storm by Robert Knox Sneden

Kelly’s Ford, from Images of the Storm by Robert Knox Sneden

On the Picket Line at Kelly’s Ford

Diary of 1st Lieut. Edgar P. Welling,

Co. C, 150th New York Volunteers

Week commencing Aug. 23, 1863

Every thing during the week has been very quiet, in fact it has been genuine camp life in the field with us, all matters incident to the camp having come up. In the morning Co. skirmish drill from 5 to 6. Breakfast at 7. From this to 5 P.M. nothing doing except street policing for a short time. Then we are on the foot in Battalion or Brigade drill until near twilight. Then dress parade. Nevertheless I have worked very hard. Had a great deal of Co. duty to perform, the muster roll for pay having to be made out which was a much greater job in consequence of the disarrangement of papers and affairs, many essential papers and memoranda being lost in the marches of the regiment. Also the Co. has been in a miserable state as far as arms and accoutrements are concerned, these must be put in proper condition, and clothing drawn and issued. To insure myself against loss, &c. I have found it necessary to take a complete inventory of all arms, accoutrements and camp equipage in the Co. This I found to be quite a task under the circumstances.

Friday morning, went on picket at Kelly’s Ford. Found no remarkable change from the week before. At the Ford the Rappahannock runs nearly South, the water is of a red, muddy color, the stream if in the northern states would be considered little more than a creek, being generally from 75 to 150 feet in width. Just above the Ford are quite rapids that keep up an incessant roar. The Ford is easily crossed in ordinary times, at present however the water is nearly waist deep. On the west bank or edge of the stream, in the water may be found plenty of shot and shell and even pistols, carbines, &c., which were left behind by Bank’s army in its retreat of ‘62.

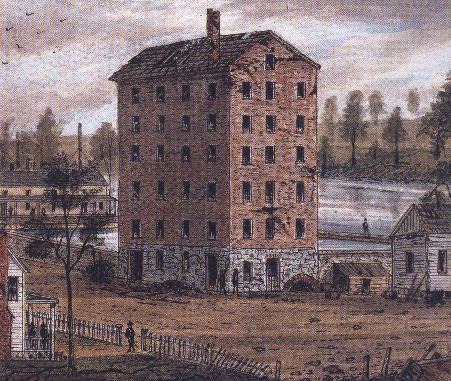

Kelly’s Ford takes its name from a Mr. Kelly who owns or rather owned all the land in the neighborhood on each side of the river. Just by the Ford is a large brick mill, a store, a blacksmith’s shop and various other buildings. Here has been one of those little villages that in times past flourished in the Southern States. The whole affair is not as extensive as Hibernia, the buildings are all on the west bank of the river.

This Kelly is an errant rebel, his son is now in confinement by the Federal Authorities. The old man must be reaping the full benefits of his folly, his lands are occupied by both the Union and Rebel armies, everything about him is nearly desolated, his outbuildings are fast falling into decay, indeed the ruins of buildings are now found on all sides, fences have almost entirely disappeared.

The Rebels when they passed through here took every thing from the old man that they considered of service to them, and when our forces were camped on that side of the Rappahannock they cleaned him almost entirely out, suggesting to him that that was the Rebel style when in Penn. I took a view of the old fellow through a field glass, prompted to by hearing him so much talked about. I found him to be one of those big, burly visaged chaps that at once suggest that nothing troubles them sufficiently to cause them to lose flesh no matter what may occur. He seems to be between sixty and seventy years of age. He is said to have owned about a hundred slaves at the outbreak of the war, but very few are seen about him now.

In the morning one of the pickets reported to me that a rebel cavalry picket had come down near the river and signaled, waving a paper or handkerchief. I immediately went to the post of the picket when the Rebel again waved what appeared to be a paper. He wished to exchange papers, saying that he had a North Carolina paper. I wished much to exchange but the advantage of exchange is always with the Rebels. There is also an order against exchange or holding conversation across the river, though it is much done. This Rebel appeared to be the Lieut. of the Rebel picket, he was fine looking and quite gentlemanly in his manner. I told him the river was rather deep to wade. He thought so too, and saying he was very sorry we could not exchange, he bade me a very good morning and turned on his heel, remounted his horse and waving his hat, galloped away. There is something interesting about one of these interviews though nothing of importance occurs, the circumstances are somewhat peculiar.

We were relieved early Saturday morning on an order to change camp, arriving there I found, much to my satisfaction, that the order had been countermanded, as I had much to do to finish my Co. muster and pay rolls, worked at them and finished them today.

The weather during the week has been fine. A shower or two with some quite hot days though cooler than some last week. Our regiment is not very healthy, much sickness being prevalent among officers and men. My health has been better than I could expect under the circumstances.

Our camp is about half a mile back of Kelly’s Ford on a piece of sward land. The whole Division lies close by. The land hereabouts looks tolerable though it does not appear to have been as productive as it should, needing better cultivation. There is much forest land about here, the trees are nearly the same as in Dutchess, there is a great deal of pine and some cedar also. Just to the left of our camp in the wood, facing from the river are the ruins of a large tannery, burned down during the war. Indeed on every hand one may see the desolating effects of war. The only crop now visible is corn and that will not be worth gathering as the soldiers are taking it while green to boil, scarcely an ear in this locality will ripen, the boys are having green corn daily.

In a day or two, if able, I will draw the mill and surroundings at Kelly’s Ford, the whole affair will make an interesting picture.

Week Commencing Aug. 30, 1863.

Received orders from the Col. early Sunday morning to have Co. C ready to strike tents at 10 A.M. as he had been ordered to move camp. The object of the removal being to take a more healthy position. At ten we were ready and the whole regiment took up its line of march and proceeded something above a mile farther back upon a hill. Here we laid out our new camp, and in short order the top of the hill was whitened with tents.

The shelter tents are put up in this manner: Four crotches are driven into the ground so that they are about eighteen inches high, in these are placed two poles of the length of the piece of tent. Two other crotches about six feet high are driven into the ground midway between each two of the short ones, and a pole laid across from one to the other, two pieces of shelter tent are then buttoned together and thrown over this pole and fastened at the sides to the poles placed there, this forms a complete roof. Across the lower poles other poles are laid, for a bed, being thus raised some 18 or 20 inches from the ground. Upon these pine and cedar boughs are laid, and over them an India rubber blanket, thus a very comfortable bed is made. A shelter tent is about six feet square made of very light canvass. Some of the men regardful of their comfort thatch up one end of their tents with cedar boughs. Some build little arbors in front of their tents to shut out the sunbeams. In this way our little camp was soon made to present quite a grotesque and at the same time comfortable appearance.

Our location is a delightful one, the hill upon which we are encamped is crowned by a piece of wood, this lies just back of our camp, (the hospital department, the band and the horses and hostlers,) is in the wood. The hill slopes to the northwest, below it is the valley of the Rappahannock with its meadows and pasture fields, pieces of corn and woods. Far off in the distance are the Blue Ridge mountains, so quiet and grand that one never tires of looking at them. I sometimes forget myself as I look across the country towards these mountains and think that I am again in old Dutchess with the Catskills in view, but the sound of drum and bugle, the hundreds of tents dotting the valley below and the desolate appearance of the country quickly remind me that I am on belligerent soil and in the old Dominion.

To our left is Kelly’s Ford at a distance of a mile and a half, to our right is Bealton Station some five miles distant. In that direction there are more signs of civil existence, even some farm houses may be seen which keep about them an air of comfortable life - their very sight is refreshing. In one of them Gen. Slocum (the commander of our corps) makes his headquarters. By Sunday night we were very comfortably quartered for troops of the Army of the Potomac.

Monday was the day to muster for pay. The muster took place at ten A.M. and occupied the larger portion of the day. Everything passed off well as could be expected under the circumstances. At night, much fatigued and feeling a little rheumatism, I turned in with an India rubber coat for covering and slept soundly.

Tuesday, about 8 o’clock P.M. received order to go on picket with Capt. Green and some 76 men and the necessary complement of non-commissioned officers. Marched to Brigade Headquarters, and received instructions to proceed to Kelly’s Ford and hold ourselves behind the breastworks as a reserve to the forces already there, the Rebels having strengthened their picket force and thrown it nearly down to the bank of the river. Arriving at the place, we found everything quiet so we stacked our arms, and leaving three men to guide them, with instructions to wake us in case of undue stir on the other side. We wrapped ourselves in our blankets and slept the night away, nothing transpiring to disturb our slumbers except the dampness and chill of the night air.

Wednesday morning, found everything quiet; I noticed a few more Rebel pickets than when I was on duty before and that their lines extended farther down to the water, nothing however of a decidedly belligerent character evincing itself, at 8 o’clock we started for camp. Arrived there at nine. Lieut. Marshall was just starting for Washington, very sick with typhoid fever, bade him good bye and saw him safely started in an ambulance.

Nothing of importance, in a military point of view, has transpired during this week, ordinary camp duty being the only thing on the agenda, no Brigade drills and few Battalion. The weather some part of the time has been quite cool, especially nights. My health during this week has not been as good as on previous weeks, owing to a change of weather probably. Saturday closes in once more, but there is little to indicate that tomorrow is the day set apart for universal rest.

Camp Near Kelly’s Ford, Va.

September 12th, 1863.Things about Kelly’s Ford are very much the same as one week ago. Nothing of particular note having occurred. Sunday was a beautiful day. My duties are principally confined to looking after Co. C. At nine in the morning had an inspection of the company; found a decided improvement in the company in almost every respect; the men by a little encouragement on my part have taken great pains in presenting a better appearance. Indeed the whole regiment is much improved in this respect. It is almost surprising to see how well men can keep themselves looking while in the field. More surprising when one looks about camp, down here in the Army of the Potomac, to observe how comfortable the different regiments make themselves with a few pieces of muslin, some poles and boughs. The men, many of them are very industrious and quite ingenious in devising ways to provide for deficiencies. Every part of a camp is also kept with the utmost neatness. It makes no difference whether a regiment stays in camp two days or two months, you will generally find things in the same way.

On Monday went on picket at the Ford. Found little change across the Rappahannock among the rebels pickets. A few more, however, were visible, and these were bolder than I was accustomed to see them. The barbarous practice of picket firing being done away with, pickets, as posts of observation, no longer conceal themselves from view or evince any fear of approaching each other’s lines.

Quite a contrast presents itself between the men of the opposing armies. Our men, with their dark blue apparel, which at a distance looks almost black; the rebels, with their grey and butternut, which is scarcely distinguishable among the trunks of trees, logs and fences. In this respect I think the advantage, especially in the line of sharpshooting. Our pickets are now within easy rifle range of the rebel pickets. No picket is allowed to point a gun toward the rebel lines, or in any way give indication of a belligerent character. Picket duty in nice weather is rather pleasant, there is nothing hard about it. We leave camp about nine in the morning, and we relieve the picket guard at the post, and throw out a relief to relieve that on sentinel posts; the picket on post then return to camp. There is always kept at a small distance behind the line of sentinels (the pickets on post) a reserve ready for every emergency. One half of these are allowed to sleep, eat, &c., at a time, the others must be ready to spring to arms at a moment’s notice. The officer of picket has a mounted orderly at hand to send to headquarters with news of anything important which may occur, and with the utmost dispatch. When things are considered a little dubious an extra reserve is added at night. The day passes generally without anything exciting. At night, however, are many quite laughable occurrences. Some men of active imaginations see many things to excite suspicions. Passing along my line of pickets one of the sentinels beckoned me to come to his post. I could not perceive whether each particular hair did not stand on end like a fretful porcupine or not. Says he: “Do you see that bush?” “Yes,” said I. “Is there not a man by it?” “None that I can see,” I replied. At that instant a dark object moved very low down, as a man on his hands and knees. The thing grew very interesting. It moved from the bush, came out in the moonlight, and Mr. Kelly’s, or somebody else’s big black dog developed his proportions, trotted down to the water’s edge, took a drink, and trotted back as any other dog would have done. The sentinel did not wish to hear any more about dogs that night. Occasionally one hears of men who wear even first lieutenant’s straps becoming somewhat nervous at a few cattle or horses roving among the bushes on the other side of the river, but perhaps it is better so, but as yet I have seen nothing while on picket to disturb me. At night, the men not on duty for the time being, wrapped themselves in their blankets, and sleep much more soundly than many citizens at home in their beds do, while the wheel of conscription continues to roll. The officer of the picket is expected to be constantly on the alert. Everything depends on him; he must have much discretion to do his duty properly; he must not let the enemy steal a march on him, nor must he unnecessarily alarm a camp.

Tuesday morning came off picket; found everything quiet in camp; spent the day in writing up company matters; doing company business, drilling, and other camp duty.

Wednesday morning refused duty for the first time since joining the regiment at this place; was quite indisposed from diarrhea; towards noon grew better and went on duty. In the afternoon we had a review of our brigade, consisting of three regiments. A review of this kind I had only once before seen, that at Camp Millerton. It passed off well. Immediately after the review of our brigade, the First Division of our Corps, consisting of six regiments, was reviewed. Some of the regiments had received their quota of conscripts, consequently they made a very good show in point of numbers. The line was at least three-quarters of a mile in extent. In these reviews I find that the 150th compares very favorably in point of drill.

Thursday morning went on as regimental officer of the day. At one o’clock the regiment was in line ready to join its brigade and division review, being officer of the day, of course I was excused. The review is said to have passed off to the satisfaction of all concerned. At its close the surrender of Ft. Wagner was announced to the division. The announcement was received with three hearty cheers. Good war news are quite as favorably received among us as among the most patriotic at the north. That night our regiment was visited by some staff officers of the division, all much intoxicated, and they were more so before they departed. One of them, a quartermaster ranking as captain, rode his horse into a sink. The horse fell and threw his ride, breaking his arm and bruising him somewhat. When the quartermaster came to and found his arm broken he said, “Well, by G-d, I’ve broken my arm over the fall of Wagner. I shall break my neck over the fall of Charleston!” Good patriotism; but the question arises whether such men are calculated to take a place like Charleston? But these fellows felt jubilant at the fall of Wagner and got drunk over the news.

Friday passed with nothing worth noting. Battalion drill from 5 o’clock until dark. In the morning cannonading could be heard plainly on our right somewhere in the region of Rappahannock Station; since learned it was a reconnaissance of our forces on the other side of the river.

Saturday opened fair and beautiful, very warm at noon day. About 2 o’clock rising far above the sleepy Blue Ridge, could be seen a dark mass. We inhabitants of cloth houses looked somewhat apprehensively towards it; it rose higher and higher; grew darker and darker, until it overspread the whole sky, and then came a deluge of wind and rain. And our clothe houses and piney arbors? Alas! They proved to be founded upon sand. I felt my tent going. Instantly wrapping a rubber blanket about my books and papers, I bade the tempest to do it’s worst. And it did. Down came poles, tent and all completely wet through. The wind and rain abated, crawling out from under my prostrate tent a most laughable scene presented itself. Officers and men on all sides were creeping out from under the enveloping folds of fallen and saturated tents. Wet through, hats off, many of them swearing, and all laughing at each others laughable plight. Scarcely an officer’s tent was left standing and they were all more or less wet themselves. The sun came out beautifully bright and was welcomed with much better gripe than for the past few days. Tents were soon up, everything dry, and in one hour little indication of the scene described was visible. Just before sundown General Kilpatrick rode through our camp to join his command just under the hill. This looks like some movement in the neighborhood, for several days the indications have been that something is on foot.

My health during the week has not been very good. Have had quite a bad case of diarrhea. It still clings to me with but little abatement. Very few escape it when first coming into Virginia. If not too severe and persistent one is benefited by it. It often prevents fevers.

Lt. Welling died of Typhoid Fever on Oct. 21, 1863.

Written on the Death of Lieutenant E. P. Welling

The lightning flash o’er the distant wire,

A solemn message sped;

Speak gently the news to a loving sire,

For a cherished son is dead.At his country’s call, with high resolve,

He went to the tented field,

A foe to quell, and treason absolve,

Or his richest blood to yield.‘Twas hard to part, and a mother’s eye

With a loving tear dim,

When he came to say a last good-bye,

Oh! Could she give up him?And hard to see that manly form

Lie motionless in death;

And harder still, when the clods went down,

To resign him to earth.We mourn thee, Edgar, for manly worth

Was stamped upon thy brow;

And thy placid look and well-known voice,

For aye, are departed now.A link in our social chain is broke,

A family tie is riven,

To be resigned to this cruel stroke,

May Christian strength be given.

The Mill at Kelly’s Ford, from Images of the Storm by Robert Knox Sneden

On The Picket Line at Kelly’s Ford

(on the website of The Bivouac)

Return to the 150th Regiment Home Page