|

Read extended version at

CWI

Also online at:

Religion, slavery and 'Stonewall'

Jackson (FLS 12/23/06)spacer

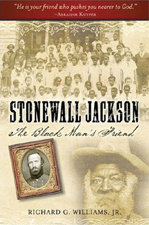

Stonewall Jackson "The Black Man's

Friend" by Richard Williams

By Michael Aubrecht, FLS Town &

County

Date published: 12/23/2006 CIVIL WAR

Most people with even a casual

interest in the Civil War are familiar with the

importance of religion in the day-to-day life of

Confederate Gen. Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson.

However, what they may not be aware of is how much

of a role he played with regard to the

implementation and promotion of religion before,

during and ultimately after the war.

In

addition to being one of the South's most fearsome

commanders, Jackson was also instrumental in the

formal establishment of military-based chaplains in

the Confederate army. As a devout evangelical

Christian, he was actively religious and held the

civilian position of a deacon in the Presbyterian

Church. Throughout his participation in the fight

for Southern independence, Jackson adamantly

maintained the rituals of his faith while on

campaign, and his steadfast allegiance to God

became infectious throughout the ranks.

Despite Stonewall's popular and

one-dimensional legacy as an Old Testament warrior,

his prewar contributions may provide us with an

even greater appreciation for the man, more so than

his achievements on the battlefield. Most notable

are his charitable efforts on behalf of local

African-Americans, including the rarely discussed

establishment of the first black Sunday school in

Lexington. It is this kinder and gentler side of

the Christian soldier that provides the basis for

author Richard G. Williams' latest book, titled

"Stonewall Jackson: The Black Man's Friend."

The

obviously complex and somewhat paradoxical

relationship between Southern Christians and their

slaves has been a long-debated topic among Civil

War historians and enthusiasts.

Many critics have questioned how

the Confederacy could fight for its own freedom in

good conscience, while denying the very same

liberty to the African-American population. Others

contend that slaves actually benefited spiritually

by being baptized into the Christian faith while

being held in captivity.

Thus, a book like this may be

viewed differently according to one's own

preconceived notions of faith and race relations.

As

a seasoned author whose other works include

"Christian Business Legends" and "The Maxims of

Robert E. Lee for Young Gentlemen," Williams is

well aware of this dilemma, as well as the merits

of both sides of this argument. He strives to

address all aspects of it in a fair and balanced

manner. His message lies in finding the positive

stories that are too often forgotten when

discussing the racial divide of the antebellum

South and its influence and impact on the lives of

the minority population.

Unlike previous studies that have

been published on Stonewall Jackson's prewar life,

this book required a level of preparation that went

well beyond the scope of most secular studies. In

order to tackle subjects as highly contested and

sensitive as slavery and religion, Williams

understood that he must first be willing to present

an honest representation of the sins of bondage in

all of its unpleasant details.

He

also recognized that he would have to take the time

required to meticulously research the matter while

using primary sources in an effort to establish

balance and accuracy.

Frankly, it takes guts to write a

study like this and Williams has shown the same

courage and tenacity that Jackson did at the First

Battle of Manassas.

Adding to the credibility of his

efforts is the validation by nationally acclaimed

Civil War historian, Jackson biographer and

historical consultant to the film "Gods and

Generals" James I. Robertson Jr., who has written

the foreword to the book. He states: "Exhaustively

researched, teeming with useful nuggets and written

with an undertone of faith that Jackson himself

would have admired, this study clears the air of a

lot of myths, accidental and otherwise. The

narrative surprises and informs, memorializes and

inspires, all at the same time."

Williams begins this journey by

painfully depicting the deplorable trials faced by

African-Americans as they were shipped from the

slave-trading colonies in Africa to the coastal

cities of the United States. Along the way, we are

reminded of the horrible conditions and

mistreatment faced by these prisoners, and the

author holds nothing back in the telling. He then

presents the social, political and financial

aspects of slave trading and the history of its

institution and practice in 18th- and 19th-century

America, as well as the shared shame that fell

equally on the North and the South.

This provocative opening provides a

solid foundation for the story that is to come.

Clearly the examples that follow, depicting the

compassion and care given by a percentage of

Christian Southerners on behalf of a poor

mistreated people, need to be recognized in order

to find something righteous beneath so much

suffering.

Thomas Jackson's efforts are

certainly worthy of such recognition, as

contradictory, at times, as they may sound.

Therefore, Williams continues to focus his

attention on Stonewall's own path to sharing the

message of salvation while citing the positive

influence that his fellow believers had, in turn,

on him.

As

devout Christians, the Jackson family fervently

believed that all people were welcome at the Lord's

table regardless of their race or social stature.

As a result, he and his wife were instrumental in

the 1855 organization of exclusive Sunday school

classes for blacks at the Presbyterian church.

Although Jackson could not alter

the social status of slaves, Williams tells of how

he committed himself to Christian decency and

pledged to "assist the souls of those held in

bondage." He also adds that Jackson and his wife

were guilty of practicing civil disobedience by

educating slaves.

Eventually the Sunday school grew

beyond the allotted facilities and ultimately

blossomed into new churches for African-Americans.

In this regard, we can see how the evangelical

white Christian slave owner had a positive

influence on the spiritual education of those held

in captivity. As a result, many ex-slaves became

preachers themselves and were later responsible for

some of the largest religious revivals that

followed the South's surrender.

Above all others, though, the most

inspirational stories from this book came out of

the classroom itself. It is pleasant to read the

accounts that were written by former slaves who

leaped at the opportunity to learn to read and

study biblical Scriptures. Their intellect and

enthusiasm were evident in their writings, and it

is compelling to see how they, in turn, impacted

the church's white congregation. The resulting

fellowship that was shared between these two

communities continues to this day.

In

a most fitting conclusion, Williams shows the

fruits of Jackson's labor by visiting Lexington in

person and sharing the stories of several local

residents whose ancestors were participants in

Stonewall's school. Through personal interviews,

the author is able to publicize several

generational stories that would not have been

shared outside of the family if not for his book. A

large percentage of these African-Americans hold

the memory of Thomas Jackson in the highest regard,

and all of them are thankful for his influence on

their ancestors.

In

the end, it is not that difficult to believe the

notion of a Christian slave holder showing

compassion and mercy in fulfilling an obligation to

"make disciples of all nations." This book

reinforces the reasoning as to why a Christian

Confederate would go to such lengths to educate and

enlighten slaves. Simply put, Thomas Jackson did

exactly what his Lord had told him to do. He spread

the Good News to everyone. His "students," in turn,

accepted Jesus Christ as their Lord and Savior and

eagerly continued to spread this message as they

left the cotton fields and entered the mission

field.

So

inspirational is this story that a film company

called Franklin Springs Family Media, run by

award-winning Christian film producer and director

Ken Carpenter, is currently producing a documentary

based on Williams' book, titled "Stonewall Jackson:

His Fight Before the War." The movie is currently

in the production phase and most of the filming has

been completed. You can view the trailer for this

film at franklinsprings.com/stjtrailer.

In

an e-mail interview with me, Williams discussed his

motivation behind the project. He stated, "The book

was a labor of love that took four very enjoyable

years to research and write. Growing up and living

in the beautiful Shenandoah Valley that Jackson

called home for the last 10 years of his life, I've

always been keenly interested in Jackson. Having

been a Sunday school teacher myself for the last 27

years led to a natural curiosity in Jackson's

ministry to slaves and free blacks."

He

added, "As I researched what led Jackson to start

this most unusual ministry, I was struck by the

poetic justice of the story. Slaves likely first

piqued Jackson's faith, and this faith eventually

led him to reach other slaves with the gospel,

despite the evils of slavery. It is truly an

amazing story."

It

is an amazing story, indeed, and one that has been

waiting for a very long time to be told. For more

information on "Stonewall Jackson: The Black Man's

Friend," visit Richard Williams' Web site at

www.SouthRiverBooks.com.

MICHAEL AUBRECHT is a Civil War author and

historian who lives in Spotsylvania County. For

more information, visit his Web site at

pinstripepress.net. Send e-mail to his attention to

gwoolf@freelance star.com

|