CHAPTER 4: Ojczyzne Wolna, Racz Nam Wrocic, Panie - Conditions in Post-War Poland.

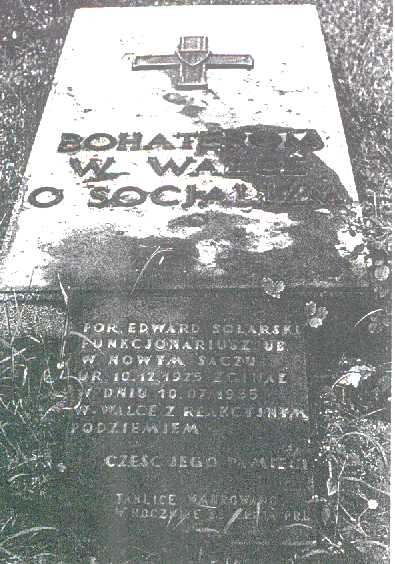

"A HERO OF THE STRUGGLE FOR SOCIALISMKILLED IN THE FIGHT AGAINST THE REACTIONARY UNDERGROUND"

"A HERO OF THE STRUGGLE FOR SOCIALISMKILLED IN THE FIGHT AGAINST THE REACTIONARY UNDERGROUND"

The link between Poland and religion is possibly best expressed in one hymn that invokes God to protect Poland:

Boze cos Polskie przez tak liczne wieki,

Otaczal blaskiem potegi i chwaly,

Cos ja oslanial tarcza Swej opieki

Od nieszczesc, ktore przygnebic ja mialy:

Pzred Twe Oltarzem zanosim blaganie:

Ojczyzne wolna pobogoslaw Panie!

God, who for centuries, has given Poland both

Glory and might;

Who has preserved Her with Your sacred shield

From enemies always ready to engulf Her,

To Your altars, Oh God, we bring our fervent prayers,

Bless our free homeland.

[1]

The Polish Forces hymn and prayer book, published in 1942, had one major alteration to the hymn; the last line had been changed from: "Bless our free homeland" to "Give us back our free homeland" - the variant of the hymn adopted as an alternative national anthem under the Russian Partitions of the 19th Century. After the end of the Second World War the Polish Church reverted to the pre-war version - except for a period just prior to, and under, General Jaruzelski's Martial Law when the Church felt itself powerful enough to declare that Poland was not free. In the Church of the exiles the wartime version continued to be used and has only recently, with the return of democracy to Poland, has the old version been restored. It would appear then that opinion was divided as to whether Poland was free or not. In the case of the hymn the difference was on the grounds of politics. The Church knew that Poland was not free but to preserve its position it was prepared to accept what it had to.

Whereas the Poles knew that Poland had not been liberated by the Red Army, even the Communists who cared to think about such things knew that the Poles were not masters in their own house. The official history of the war, as published by 'People's Poland' did not enter into such polemics over freedom and justice, similarly the Soviet historians were content to expound the idea that all was well in the Soviet bloc. As the "History of the USSR, the Soviet Period" reads:

" In the course of its winter operations the Red Army, together with a Polish Army, liberated Poland from the German occupier and returned to the Polish people the lost land in the West formerly taken by the Germans. On the 21st April, 1945, a twenty year Soviet-Polish treaty was signed about friendship, mutual assistance and post-war co-operation." [2]

The fact that the Communists pushed this line is not so surprising, what is more difficult to accept is how, after the war, many western Governments blindly trusted the Soviets and put aside the natural scepticism so necessary in international relations.

The recognition of the Moscow backed Polish Provisional Government in Warsaw was one act that many of the exiled Poles considered as a betrayal. The French Government of De Gaulle comes in for particular criticism, not simply because it recognised the Communists, after all most of the other western Democracies recognised them, but, according to Tadeusz Modelski, because he was the first. The French recognised the Provisional Government on the 31st December, 1944:

"...six weeks before the Yalta Conference of 4th-11th February, 1945, and 30 weeks before the United States and Britain recognised the Government, and even 5 days before Stalin did. This degrading, servile and unfriendly act of De Gaulle's reckoning for the support of Stalin and the French Communist Party will always be remembered with scorn and aversion by the people of Poland." [3]

Although it was not only the French who were criticised for recognising the Provisional Government on grounds other than strategic. On the 29th May, 1948, "The Economist" launched an attack on the policy of Churchill with regards to the 'Polish problem':

"But a general election was impending in Britain and the Conservative Party wished to demonstrate to the electorate that it was not anti-Soviet and that it had 'solved' the Polish problem. The recognition of the bogus "Government of National Unity" was announced on the very day of the election, though, as it turned out, it did not help Mr Churchill very much." [4]

But this was written at a time when the 'Cold War' was gaining momentum. The Communists in Czechoslovakia had just taken power and the Berlin Crisis was about to break onto the scene so perceptions towards the Communists were changing. Prior to this, attitudes in many Western countries had been quite positive towards Moscow and its acolytes, yet given the benefits of historical hindsight it seems unbelievable that experienced and worldly politicians could have been taken in by Moscow.

From 1939 the Poles in the West had been warning the British that the Soviet Union was not to be trusted, and when the Soviet Front swept into Poland from 1943 onwards the Poles had shouted, to anyone who would listen, that the Red Army was not coming as liberator but as conqueror, and again they were ignored and called 'Polish irresponsibles', anti-Soviet and fascists. The question that must be asked is how justified were the Poles in claiming the conditions in post-war Poland were not to be endured and how justified were the British in dismissing their fears as anti-Soviet propaganda ?

Captain Turowski, the Chief Polish Base Censor of 2 Polcorps, in a report to AFHQ in June, 1945, wrote:

"Nearly in every letter written by an officer or a soldier one can find some sentences expressing their great disenchantment which brought them the end of the war. "The war is over, all are looking to go home, to their sweethearts, mothers or friends, but we Polish Airmen which fought in Battle of Britain and soldiers from Monte Cassino are waiting in dark !" The soldiers realise that they can't go back to Poland, because a life under unceasing fear of the arrest or deportation would be unbearable. [...]

In general the letters are increasingly pessimistic, full of sorrow and of a bitter disappointment. "There is nothing to do now, a lot of time which rests - makes the situation tragic, we have now plenty of time to discuss and worry about our future. Results: pessimism and the atmosphere of uncertainty and apathy." [5]

This mood of despondency was something that the British had to overcome as best they could. What the British could not overcome was the deep-rooted and endemic hatred of the Soviet Union, not only as a political system but as the successor of an empire that had removed Poland from the map of Europe. As one officer explained, and whose comments were subsequently removed by the Polish Base Censor:

"I am feeling unhappy and sad as I have never been since the Germans invaded Poland in 1939. You certainly will ask why? Because the dirty Bolsheviks have invaded once again our beloved fatherland. They are just now on the outskirts of Warsaw. It means for us that Central and maybe West Europe will be under the Bolshevik domination. It means for us that half of Poland will be occupied and annexed by our eternal foe. It means that the best men of Poland will be killed or deported to the labour camps. It means the annihilation of the Polish nation.... Please remember that my grandfather was deported in 1863 into Siberia and he died there. My father was buried alive by the Bolsheviks in December, 1917. My brother was killed in the battle against them in 1920. And myself with my family was deported into Russia in 1939 where I lost my wife and daughter. And now will you please ask yourself what would you feel on getting the news that Bolshevik hordes have come again into the heart of Poland." [6]

It was to this type of soldier that Bevin's appeal was directed, but it was against generations of inherited anti-Russian feeling that he had to contend.

Polish morale was low and the British knew it. The Resident Minister at AFHQ sent a report to the Foreign Office on June 23rd, 1945 which outlined some of the more obvious criticism coming from the Polish ranks. The apparent submission of the British Government over the 16 Home Army leaders who had been arrested by the Soviets and taken to Moscow for trial was one issue causing dissent among the Poles as was the forthcoming election in Britain - a change of Government could lead to an even worse change of policy. [7]

The Soviet authorities were quick to establish control over Poland and the establishment of a pro-Moscow Government was just the first step to changing the whole political system there. Trying to avoid charges of Imperialism, Soviet Histories put a slightly different emphasis on events in Poland. Grigory Deborin in "30 Years of Victory" writes:

"The Soviet Government viewed the Polish patriots' aspiration to create their own democratic statehood with understanding and profound approval. It set up no administrative bodies of any kind on Polish territory, but handed over all powers to the people's representative body. This decision was formulated legally in the agreement between the Soviet Government and the Polish Committee of National Liberation on the relations between the Soviet Command and the Polish administration.

[...]

The formation of an executive body in liberated Poland gave rise to an outburst of fury from the Polish Government-in-exile, which was in London and divorced from the people. It had now become illegal and had finally had the ground cut from underneath its feet.

[...]

These manoeuvres by Polish reaction could not impede the process whereby people's power was established and consolidated in Poland. The Polish Committee of National Liberation confidently led the people towards the goal of creating a strong and independent Poland." [8]

Whereas many Communists and fellow-travellers followed Moscow's line the Polish exiles could not. According to Jan Ciechanowski, formerly Polish ambassador to the USA, writing in 1948:

"The very composition of the Soviet-sponsored Committee of Liberation clearly showed Stalin's intention. He had placed at the head of this outfit a notorious Communist, an agent of the Comintern, who used the alias 'Bierut'. This agent had for years been a Soviet citizen, though he was of Polish origin. He had always been entirely subservient to Moscow." [9]

While the Communists were becoming firmly established in Poland Moscow was claiming that it was by the will of the people rather than at the point of a bayonet, the British Government was willing to go along with the fiction, for public consumption at least, in order to maintain Allied unity. As Churchill declared to the Commons on 15th December, 1944:

"...the fate of the Polish nation holds a prime place in the thoughts and policies of His Majesty's Government and the British Parliament. It was with great pleasure that I heard from Marshal Stalin that he, too, was resolved upon the creation and maintenance of a strong, integral, independent Poland as one of the leading Powers in Europe. He has several times repeated these declarations in public, and I am convinced that they represent the settled policy of the Soviet Union." [10]

Churchill's public confidence in Stalin's word was not shared by all the British in senior positions. As Sir John Slessor, the Mediterranean Air Commander whose planes flew to relieve the Warsaw Rising with a horrendous loss rate, explained:

"How, after the fall of Warsaw, any responsible statesmen could trust any Russian Communist further than he could kick him, passes the comprehension of ordinary men." [11]

Although many Poles feared the worst about life in Poland under the new regime some were prepared to take them at face value and see what conditions were like. Karol Popiel, himself a repatriate, explains the spirit of self sacrifice that led some Poles to return:

" The regime holds out its hand for co-operation and mutual coexistence. Somebody, despite their doubts, has to find out if its being honest. Someone has to put their head on the block and, if there is treachery, show the world that it is a deception. We returned, we took up the challenge, we lost. [...] Nearly everyone went to prison but the country was clear that the Christian leadership was not shooting from the other side of the fence but were there in person...." [12]

The idea that conditions in Poland could only be changed from within was taken up by the Polish Peasant Party [PSL] under its leader Stanislaw Mikolajczyk. The 1945 New Year edition of the PSL paper "Jutro Polski" explained why the Party was returning to Poland:

"We fight for the spirit of the nation, for its ideals and values, for the economic reconstruction of the country, for the development of the economy and of culture. We want to lead that struggle in Poland, where our place and destiny is." [13]

Whereas Mikolajczyk considered his duty was in Poland, others in the exile camp, Anders in particular, considered him and the PSL leadership as nothing less than traitors. The newspaper of the 5th Kresowa Division, the "Wiadomosci Kresowej", virtually called Mikolajczyk a traitor in an article titled "The Black Roll of the Polish Quisling":

"...Mikolajczyk - together with his associates will one day stand before a tribunal in a free Poland to face just punishment for his guilt which stems from his false ambition, his petty character, his lack of scruples and his servility.

No one can convince us that such an agent of others' interests is a 'defender of a really independent Poland'. Mikolajczyk's professed 'opposition' is, in reality, a smoke-screen to hide the final bloodletting of the living organism that is Independent Poland, and of which we are an organ." [14]

Churchill had convinced Mikolajczyk that he had to return to Poland to play his part in the Provisional Government for the good of Poland and many people in Poland read a great deal into this supposed support. Stefan Korbonski wrote in his dairy on the 30th July, 1945:

"...all these people believe that Mikolajczyk has come with the approval of the British and American governments, bringing a recipe for relieving Poland of its eastern guests." [15]

In November Korbonski wrote of Mikolajczyk that his...

"...popularity is based on the fact that, as every child knows, he has returned with the approval of the British and American governments in order to liberate Poland in accordance with the plan he has drawn up with them. The Communists laugh at this but let them laugh, everyone thinks. "He laughs best who laughs last". Surely Mikolajczyk wouldn't be so stupid as to come on his own with nothing at all." [16]

The sad fact was that did return to Mikolajczyk Poland with nothing more than a vague promise of support from Churchill and no word of what would happen if things went wrong and the plan fell to pieces. The PSL thought they were doing their best for the country but before Mikolajczyk left Britain Anders made one final attempt to convince him not to go and to preserve the unity of the Polish exiles. Anders, in his memoirs, recounts his conversation with the PSL leader:

Anders: "I should like to express my conviction that you are not only committing a grave error, but that you are also acting to the detriment of Poland. [...] You have too great a political standing to endorse, by your consent, this new partition of Poland. Our generation and those to come will curse you for that. World public opinion will be misled, if only by Soviet propaganda, into thinking that everything that has happened has been in agreement with the Poles. [...] You will have no influence on the course of events in Poland; on the contrary, you will be gradually eliminated. The decisions of Yalta are a crime against the Polish nation. And we Poles - that means you also - cannot be party to them".

Mikolajczyk: "You are wrong, General. I am deeply convinced that I shall contribute to Poland's retaining her independence. [...] I consider that Stalin is interested in having a strong Poland, and he has told me so more than once. I am sure that the elections will prove the great support I have in Poland. After these elections a democratic government will be established there."

Anders: "You deceive yourself about the elections.... I have no doubt that you would have not only the support of the men of your party, but also of all decent Poles, simply because they would like to show their real attitudes towards Soviet Russia. That is why I am convinced that the elections will be faked, just as they were faked in our eastern territories in 1939. [...] I am afraid that within three months of the falsified elections, you may find yourself in prison, even in my former cell at Lubianka, where you will be detained as a traitor to the nation and a spy. What is worse, I am certain you would then confess it yourself." [17]

This was a remarkable piece of prognostication; the election in Poland was held on January 19th, 1947, and exactly eight months later Mikolajczyk was fleeing for his life. Admittedly Anders' book was written ex post facto in 1949 but the general line is indicative of the polemic that was raging among the Poles at the time. Anders' idea was that if any prominent Pole was seen to be accepting the terms of Yalta then it would be seen by the outside world that all the Poles went along with them.

Jan Nowak-Jezioranski, one of the couriers between the Polish Government in London and the AK in Poland, in a conversation with Michael Charlton maintained the rightness of the exile course in not accepting the post-war settlement:

"I feel they were right not to do it. The problem was (and this was said - if I remember - by Raczynski to Eden) that if we really accept the kind of concession you try to impose on us, the union of the Polish nation will be ruined. This 'Union Sacree', he used this word, will be destroyed. All right, the cause was lost, the war was lost - but we have to think in terms of the future and to preserve unity. And this unity was preserved." [18]

As the PSL's role as the 'official opposition' disintegrated, Warsaw's Ministry of Information and Propaganda noted a mood of despondency sweeping one time supporters. According to many the PSL had made a mistake in committing themselves to working with the Provisional Government and they should have foreseen the hopelessness of their position - in many respects General Anders had had a more realistic view as he refused to collaborate. [19]

Although the Poles, with certain notable exceptions, opposed Yalta and everything it stood for, the matter was not really in Polish hands. The future of Poland was very much wrapped up in 'great power' politics and the question of how far the British and US Governments were prepared to go in promoting what appeared to be an injustice. As it turned out they were prepared to go a long way and in order to justify a breach of the Atlantic Charter political expediency had to be claimed. For Stalin this was good news as he could have a free hand in central and eastern Europe. As Jan Nowak continues:

"The Poles were asking, 'If you cannot do anything for us, please do not do anything against us; do not weaken our position. At least do not say openly that there will be no resistance, no conflict over Poland.'

I read the document where Bierut, the Polish Communist leader, asked Stalin, 'Will there be any conflict over Poland with the West?' and Stalin says there will be no conflict whatsoever. He just dismissed the idea.

You know this is what the

Anglo-Saxons did: they really offered, in advance, an assurance that 'there will be no resistance over the Polish issue.'" [20]

Churchill, of course, was aware of the nature of the Soviet Union but also how history would judge his dealings with it. In a telegram to Smuts he wrote:

"Will it be said of me that I was so obsessed with the destruction of Hitlerism that I neglected to see the enemy rising in the East? Will this somehow be my epitaph on everything that I have done from the Blitz, the Battle of Britain and onwards?" [21]

This particular burst of self-doubt came about as a result of the graves Katyn disclosure in 1943. Yet Churchill continued to be aware of the public's reaction to his dealings with Moscow. In his memoirs Churchill recounts that he explained to Stalin just why he would not be recognising the Provisional Government in Poland:

"It would be said that His Majesty's Government have given way completely on the eastern frontier (as in fact we have) and have accepted and championed the Soviet view. It would also be said that we have broken altogether with the lawful Government of Poland, which we have recognised for these five years of war and that we have no knowledge of what is actually going on in Poland. We cannot see and hear what opinion is. It would be said we can only accept what the Lublin Government proclaims about the opinions of the Polish people, and His Majesty's Government would be charged in Parliament with having altogether forsaken the cause of Poland." [22]

Churchill informed Stalin of his position here on the 8th February, 1945, yet five months later conditions must have improved to such an extent that Churchill felt himself able to do what he said he would not do and recognise the 'Lublin' Poles. In truth conditions, if anything, deteriorated in Poland but recognition went on ahead regardless. The fact was that for all the concerned words of the western politicians it was not really their problem. Churchill, at Teheran, said that the Poles would be wise to take his advice but that he "...was not prepared to make a great squawk about Lvov." [23] Giving up Poland's Eastern territory did not prove too difficult for Churchill, after all, as he told Capt. Count Lubomirski, ADC and translator to Anders: "I really don't understand why the Poles make such a fuss about those Pripet Marshes - nothing but mud." [24] But it was not Churchill's Lwow and they were not Churchill's Pripet Marshes.

A telling comment on Churchill's attitude to the post-war world came in 1943 as the Prime Minister talked to one of the British Liaison Officers in Yugoslavia. Brigadier Fitzroy Maclean recounts:

""Do you intend," he asked, "to make Jugoslavia your home after the war?"

"No, Sir," I replied.

"Neither do I," he said. "And that being so, the less you and I worry about the form of Government they set up, the better. That is for them to decide." [25]

For the Poles the question of the eastern lands was a dilemma of some difficulty. The London’s Arciszewski Government knew that, barring a miracle, the 'Kresy' were lost but the 'Big Three' were offering parts of Germany as compensation. On political and moral grounds the Poles refused to accept the loss in the East but at the same time knew that if Poland was to survive the future then she needed the industrial land in the West - the Poles could not have one without the other. If the West was accepted as compensation then they would have to accept the East was gone.

Zygmunt Nowakowski, writing an article in 1947 in "Wiadomosci" put a slightly different emphasis on the compensation issue:

"The gains in the West are just in their entirety as only part compensation, but not for Lwow or for Wilno, but rather for the terrible German crimes to which Poland has been victim. These acquisitions are a matter of justice. We deserve them to redress the wrong that the German have done Poland, even though it will not put them right." [26]

Poles of many political complexions pressed the claim for German territory, and for as much of it as they could get their hands on but like so many other issues of the time the matter was largely out of Polish hands. Whatever parts of Germany that would be ceded by the Germans would be won by the Red Army and given by the good will of Moscow.

Churchill was insistent that the Poland's western border should run down the rivers Oder and Eastern Neisse (Nysa Klodzka), while Stalin, the Poles in Warsaw and the Poles in London preferred the Western Neisse (Nysa Luzycka). Churchill's plan would have left Zielona Gora, Legnica, Walbrzych and Lower Silesia to Germany. For the Poles it appeared that Churchill was siding with the Germans against their interests and it appears that, according to Churchill's own memoirs, he was prepared to take this issue as far as it needed to go in order to keep the area German.

"For instance, neither I nor Mr. Eden would ever have agreed to the Western Neisse being the frontier line. The line of the Oder and the Eastern Neisse had already been recognised as the Polish compensation for retiring to the Curzon Line, but the overrunning by the Russian armies of the territory up to and even beyond the Western Neisse was never and would never have been agreed to by any Government of which I was the head." [27]

Not only was Churchill willing to disagree with Stalin, he was also ready to break up Potsdam and...:

"...namely, to have a showdown at the end of the Conference, and, if necessary, to have a public break rather than allow anything beyond the Oder and the Eastern Neisse to be ceded to Poland." [28]

It could be argued that it was unfortunate that Churchill did not employ the same level of commitment to protecting the Poles from the Soviet Union as he did protecting the Germans from the Poles. Churchill, during his famous "Iron Curtain" speech at Fulton, Missouri, complained about "Slav penetration deep into German territory" and the US Secretary of State, James Byrnes, in a speech in Stuttgart, told his audience that the Polish western frontier was not necessarily permanent. This fell right into the hands of the Soviet propaganda machine. A great deal of effort was put into convincing the Poles, with some success and justification, that both the British and the US were unreliable as Allies. German 'revanchism' would only be countered by the Soviet Union. As Gomulka put it:

"If ever in the future the Germans should again fall upon Poland, without the Soviet Union's help, without a Soviet Polish alliance, we should be threatened with the same fate we suffered in September 1939." [29]

As Bethell writes in his biography of Gomulka,

Churchill was largely seen to be responsible for handing over eastern Poland to Moscow and now he wanted to take away the Poles one consolation, this was bitterly resented by Poles, and no doubt many were glad that he did not win the 1945 election and so be in a position to have his final 'showdown' at Potsdam. Despite what Churchill said he might have done, the fact was that when he had the opportunity he did not oppose Stalin to any valuable degree, the opportunity was then taken away from him by the electorate of Britain and handed to Attlee - he too would not defy the Soviets and so, to quote Bethell's conclusion:

"Great Britain, war weary and immersed in a general election, wanted to wash her hands of the 'Polish imbroglio'. The idea of a crisis with the Soviet Union, much less a war, was intolerable. Anything was better than that. So Britain gave up her 'matter of honour' and broke her word towards the Poles, just as she had done in 1939." [30]

But even at this stage the exile Poles were still being criticised in many quarters for not meekly accepting the will of the 'Great Powers' and protesting an injustice. If only, some argued, the Poles would behave like the Czechs and accept the situation as it was. In 1947 G.D.H. Cole wrote his "Intelligent Man's Guide to the Post-War World" in which he asserted:

"President Benes saw, at an early stage, that the best hope for the re-establishment of a free Czechoslovakia lay in coming terms with the Soviet Union, and thus making it possible for the exiled Government to return and to reshape the country's institutions without the same sharp break with the past as befell the Poles because of the foolish intransigence of the Polish Government in London." [31]

In March of the following year, 1948, the Communists staged a coup in Prague that led to the resignation of the 12 Centre and right-wing ministers in the Government. The last hope of the anti-Communists, the Foreign Minister Jan Masaryk, was found dead on March 10th after having 'fallen' from his office window - it still remains unclear whether he committed suicide or if he was disposed of by the Communists.

The Czechs had gone along with the Communists in the hope that, given public support, they would win.

Whereas most Poles could see the folly of such an approach others took up the challenge - even though with hindsight it is now clear just how pitiful were their chances. In a conversation with W.D.Allen of the FO, Mikolajczyk described events in Poland as a battle:

"The battle for Poland's independence was now joined. In commenting upon the attitudes of Poles abroad he said rather grimly that this was now a fight and where there was fighting people were apt to get hurt or even killed. Patriotic Poles should, however, accept this risk." [32]

Mikolajczyk, who was here insinuating that he was more patriotic than those Generals who refused to return to Poland, agreed to go back and give credibility to that which had been agreed at Yalta and Potsdam. The Final Communiqué from Potsdam, signed on August 2nd, 1945, laid down the fine aspirations to which the Polish Provisional Government were meant to abide by:

"The three Powers are anxious to assist the Polish Provisional Government in facilitating the return to Poland as soon as practicable of all Poles abroad who wish to go, including members of the Polish Armed Forces and the Merchant Marine. They expect that those Poles who return home shall be accorded personal and property rights on the same basis as all Polish citizens.

The three Powers note that the Polish Provisional Government in accordance with the decisions of the Crimea Conference has agreed to the holding of free and unfettered elections as soon as possible on the basis of universal suffrage and secret ballot in which all democratic and anti-Nazi parties shall have the right to take part and to put forward candidates and that representatives of the Allied press shall enjoy full freedom to report to the world upon developments in Poland before and during the elections." [33]

Laudable as these words were, they did not convince everyone. Obviously many of the Poles in the West retained their natural scepticism over any document signed by Stalin, but there were also many in British politics, mostly Conservatives now relegated to the Opposition, who could also see just how unlikely the aspirations were to come about. Potsdam was, on the whole, a reaffirmation of the Yalta Accord and the debate over that agreement brought out the divisions in British attitudes. One Conservative, Major Lord Willoughby de Evesby, who was prepared to stand against his Government and abstain in the vote, said in the Commons:

"'...democratic principles... democratic means... democratic elements... broader democratic basis... free and unfettered elections', and so on. It would be disappointing to my mind disastrous, after the long journeys which the Prime Minister undertook to get to the Crimea and all the hard work that was done, if we found that he, the President of the United States and Marshal Stalin were not all speaking exactly the same language. In fact, a slightly different definition was given to this word by all three of them." [34]

Certainly Stalin's interpretation of Democracy was considered that which was politically expedient at the time. Alger Hiss, assistant to the US Secretary of State, recounts that at the Teheran meeting in 1943 President Roosevelt had told Stalin that many Americans viewed the Soviet annexation of the Baltic States with some anxiety and asked that in order to placate this disturbed feeling might it be possible to hold some plebiscite to legitimise events. Stalin was supposed to have "very casually" said: "You want a plebiscite? Of Course!" [35] Such was the view of Stalin towards 'free and unfettered' elections. The results were never in doubt; they were falsified in the Baltic States, they were falsified in 1939 when the Soviets had occupied Eastern Poland under the Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact and it seemed likely that they would again be falsified in Poland whenever the Provisional Government got around to holding them. The British and US Governments appeared to have more faith in Stalin and the Polish Communists than did many Poles in Poland. The Ministry of Information and Propaganda in Warsaw recorded a popular joke that was circulating in the country just before the January, 1947, election that said there would be no winter in 1946 as the "lipa" would be in bloom in January - the 'lipa' in Polish is a lime-tree and is also the word for a lie or an untrue story. [36]

Bierut, who met Churchill in July, 1945, tried his best to put forward the idea that Poland would emerge from the shadow of the war as freer and more democratic state. He told Churchill that he did not want to stop the Polish people expressing their views and that the elections in Poland would be "even more democratic than English ones, and home politics would develop more and more harmoniously." [37]

Eight months after Bierut had met Churchill the elections had still not taken place. The reluctance of the Provisional Government to put itself to the public vote began to ring alarm bells in Whitehall. The Labour Foreign Minister Bevin declared to Parliament that Britain would use its influence to make sure the Poles observed the Yalta declaration, this in turn led to an angry note of protest from Bevin's equivalent in Warsaw Wincenty Rzymowski with the accusation that Bevin was meddling in Polish internal affairs.

In Boruta-Spiechowicz's secret meeting with the Foreign Office he spoke of what might happen in the Polish elections if all things were left to run their natural course:

"Boruta considers that in free elections Mikolaiczyk [sic] would have not less than 80% and probably as much as 90% of the votes. The peasants themselves are strong and fearless and would vote up to 99% for the Peasant Party. If elections were held today Mikolaiczyk might get 70% in spite of the efforts of the present regime to arrange for the 'cooking' of the elections. The present regime is very concerned and much of its energy is devoted to securing an overwhelming vote for its own block." [38]

There was a great deal of underestimation in the capacity of the Communists to so 'cook'. Dr S. Taylor MP, in a report to Hector Mc Neil on his recent visit to Poland, expresses the view that was common at the time, that the Communist Party, or to give it its correct title of Polish Workers Party [PPR], was actually worried about the election and that the outcome was anything but a forgone conclusion.

"Strangely enough they are far less frightened of a free election than PPS [Polish Socialist Party]. This maybe because they have overestimated support for the left parties, because they intend to cook the elections, because they intend to fight if they lose, or because they realise that a free election, by splitting PPS, would favour them in the long run. My guess is 1 and 4. I doubt if they could cook on a sufficient scale." [39]

Cavendish-Bentinck, who had also read Dr Taylor's report contradicted his findings:

"I think that the reason for which the P.P.R. are less frightened of a free election than the leaders of the P.P.S. is that they are quite determined that there will be no free elections, and that whatever happens they will somehow or other manage to stay in power." [40]

This was a more realistic scenario than that presented by Dr Taylor. So much emphasis had been placed by the 'Big Three' on the Polish elections but very few British politicians by the beginning of 1946, and even fewer in the Foreign Office, believed that the elections would be anything but a sham; at best they would not be 'free and unfettered'.

The Foreign Office received a report of a conversation between Mr Bourdillon Ford and Jerzy Szapiro, a Polish Socialist. Szapiro advocated putting off the election until August, 1947. This would give the country a chance to settle down - if the political violence continued, said Szapiro, then the Soviet Army might take control of Poland. By August of 1947 "You could have a election that would be fought on the true issues." [41] This drew an untypical minute from Hankey at the FO: "Crap !!" Clearly the Head of the Northern Department remained unconvinced by Szapiro's argument. Whereas he agreed that the PPS would be the middle ground between the PPR and the PSL, Hankey was of the opinion that if elections were not held soon then there would be no PSL left, such was the campaign of repression used by the Communist security apparatus.

The elections in Poland, if the Provisional Government ever agreed to hold them, would be unsupervised by the rest of the world, despite the provisions made in the Yalta terms. This would inevitably lead to accusations of electoral abuse but the British had no plans to send monitors. The Earl of Craven brought that very point to the attention of the Government in the House of Lords on the 19th March, 1946. If the Government were sending a Commission to supervise the elections in Greece why were they not sending one to Poland? Lord Ammon, replying for the Government, declared that:

"The Polish President further assured the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs at Potsdam that the elections would be held on the basis of the 1921 Polish Constitution. If these pledges are strictly fulfilled in the arrangements made for the elections, an international Commission would not appear necessary." [42]

This begs the question; what would happen if these pledges were not strictly fulfilled? It was widely believed at the time that they would not be. By giving up the demand for international supervision the Western Powers were giving the Communists a free hand to hold the election on their terms. This, of course, did not deter the British Government from its policy of trying to convince the Polish Armed Forces under its command to return back to Poland. Not only were the Poles told that it was their patriotic duty to return but also they were told that if enough of them went back then they would make a substantial difference to the outcome of the election. The Poles pointed out the loophole in this logic that whether they returned or not the Communists would retain power in Poland by fixing the election. As Anders was later to write:

"The British decision had indeed surprised us, for it had always been my impression that no decision would be taken in regard to the Polish Forces until after elections had been held in the country. Mr Bevin, however, said that the British view had always been that the troops should return to take part in the elections. He seemed to think that their votes would really count and that by returning they would help in the attainment of Polish freedom." [43]

Anders was not alone in this view. In the FO's first "Warsaw Weekly Summary" for 1947 Cavendish-Bentinck, the British ambassador, confirmed the Foreign Office's worst fears:

"It is now clear that as a result of pre-election activities staged by the Communist Party there is no chance of the elections being anything but a farce." [44]

The world had a foretaste of Communist election fraud in July of 1946 during the, so-called, "3 Times Yes" Referendum. As officially announced the result to the three questions asked were:

1/ Are you in favour of abolishing the Senate?

Yes: 7,844,522 (66.2%)

No : 3,686,029 (33.8%)

2/ Are you for making permanent, through the future the future Constitution, the economic system instituted by the land-reform and nationalisation of the basic industries with maintenance of the rights of private enterprise?

Yes: 8,896,105 (77.3%)

No : 2,634,446 (22.7%)

3/ Are you for the Polish western frontiers as fixed on the Baltic and on the Oder and Neisse?

Yes: 10,534,697 (94.2%)

No : 995,854 ( 5.8%) [45]

The Communists campaigned for a show of support from the public that they should vote '3 x Yes', and that is what they announced the public had done. This did not convince many people. The PSL complained bitterly that the results were a fraud but due to censorship and Communist control over the means to broadcast to the

public the true message could not easily be told.

The true results in some districts did become known to he PSL. A total of 2,805 electoral districts did manage to announce their real voting figures to independent sources before the Provisional Government

could falsify them. Mikolajczyk cites one example in his book "The Rape of Poland" - The official results to question 1 in the Krakow area, were: Yes 68% No 32% but the real results, according to the PSL, were: Yes 16.46% No 83.54% [46]

The results of the national elections were even worse. The PSL was offered membership of the Government bloc or political and physical annihilation. The PSL decided to call in its support from the mass of the Polish people and stand alone. All the estimates of PSL popularity were accurate and in a free election they would have undoubtedly won so the 'official' results when they were announced did not convince anyone. [47]

| Party |

Valid Votes |

% of Vote |

Representatives |

| Government Bloc |

9,003,684 |

80.1 |

384 |

| PSL |

1,154,847 |

10.3 |

28 |

| Labour Party |

530,979 |

4.7 |

15 |

PSL

(New Liberation)

|

379,754 |

3.5 |

13 |

| Others |

157,611 |

1.4 |

4 |

| |

==========

11,244,875 |

===

100 |

===

444 |

Mikolajczyk and the PSL passed into political oblivion just as Anders and other Poles had said they would. Their obliteration was complete and with them died any hope of democracy in Poland.

The British Government was forced to concede that things had not gone according to plan. On February 3rd, 1947, the Under-Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, Mr Mayhew, told the Commons:

"Our information regarding the conduct of the Polish elections, unfortunately, confirms reports from reliable British Press correspondents, which have already been published. The powers of the Polish Provisional Government were extensively used to reduce to a minimum the vote of those opposed to the Government bloc. Opposition lists of candidates in areas covering 22 per cent. of the electorate were completely suppressed. Candidates and voters' names were removed from the lists; candidates were arrested; Government officials, members of the Armed Forces and many others were made to vote openly, and other forms of intimidation and pressure were used. The count was conducted in conditions entirely controlled by the Government bloc. His Majesty's Government cannot regard these elections as fulfilling the solemn contract which the Polish Provisional Government entered into with them and with the United States Government and Soviet Government that free and unfettered elections would be held. They cannot, therefore, regard the results as a true expression of the will of the Polish people." [48]

This was very much a case of closing the stable door after the horse had bolted. The Poles in the West had warned that the elections would not be free, the PSL by standing in the elections had given them a credibility that they did not deserve, and when everything had fallen apart there was very little that anyone could do about it - the damage had already been done.

Back in July, 1945 , when recognition had been transferred from the London Poles to the Warsaw Polish Government, Count Raczynski, the exiled Foreign Minister, wrote to his British counterpart, Anthony Eden, to protest the move:

"3: The persecution which thousands of Poles are enduring in Poland today, and which afflict with particular severity all those citizens of the Republic who have actively demonstrated their devotion to the cause of freedom and independence by their implacable struggle against the German invader, prove beyond any doubt that the so-called Polish Provisional Government of National Unity in no way represents the will of the nation, but constitutes a subservient body imposed on Poland by force from without.

4: The first attribute of the independence of a State is its freedom to chose a Government. In the present circumstances, the source of the authority of the Government headed by M Osobka-Morawski is a decision made not by the Polish nation but by three foreign powers, one of which controls de facto the whole administration of Poland through its army and police force. The legal basis of the authority of that Government can be compared with the legal basis of the authority of the so-called Governments set up in occupied countries during the war by Germany. In both cases they are based on the will of a foreign power." [49]

For the Poles there was no sense of satisfaction at being able to sit back and say - we told you so! The feeling of national disaster was all pervading and the knowledge that it was too late to do anything about it did not help. The Poles had pleaded with the British not to recognise the Polish Government in Warsaw until after the elections, then a better idea of what the Provisional Government thought about 'free and unfettered' elections. Britain and the United States had declared themselves publicly to be committed to democracy in Poland; Anthony Eden, in his contribution to the Yalta debate, declared:

"First, Is it our desire that Poland should be really and truly free ? Yes, certainly, most certainly it is. In examining that Government, if and when it is brought together, it will be for us and our Allies to decide whether that Government is really and truly, as far as we can judge, representative of the Polish people. Our recognition must depend on that. We would not recognise a Government which we did not think representative. The addition of one or two Ministers would not meet our views. It must be, or as far as it can be made, representative of the Polish parties as they are known, and include representative national Polish figures. That is what we mean." [50]

President Trueman, in a speech made on Navy Day, October 27th, 1945, echoed Eden:

"We shall refuse to recognise any government imposed on any nation by the force of any foreign power. In some cases it may be impossible to prevent forceful imposition of such a government. But the United States will not recognise any such government." [51] Provisional Government thought about 'free and unfettered' elections. Britain and the United States had declared themselves publicly to be committed to democracy in Poland; Anthony Eden, in his contribution to the Yalta debate, declared:

"First, Is it our desire that Poland should be really and truly free? Yes, certainly, most certainly it is. In examining that Government, if and when it is brought together, it will be for us and our Allies to decide whether that Government is really and truly, as far as we can judge, representative of the Polish people. Our recognition must depend on that. We would not recognise a Government which we did not think representative. The addition of one or two Ministers would not meet our views. It must be, or as far as it can be made, representative of the Polish parties as they are known, and include representative national Polish figures. That is what we mean." [50]

President Trueman, in a speech made on Navy Day, October 27th, 1945, echoed Eden:

"We shall refuse to recognise any government imposed on any nation by the force of any foreign power. In some cases it may be impossible to prevent forceful imposition of such a government. But the United States will not recognise any such government." [51]

Despite such pious platitudes to freedom and to national self determination, the fact was that, to paraphrase the then US ambassador to Warsaw, the betrayal had been legalised.

The options for action by the British and US Governments were limited. The first reaction was to break of diplomatic relations with Poland and to deny that recognition that had already been given. Arthur Bliss Lane, the US ambassador in Warsaw, forwarded a note from Cardinal Hlond to Washington on February 3rd, 1947, in which the Primate of Poland said that the withdrawal of foreign embassies would mean the end of the Polish people and would end Poland's long association with the western world. [52] The removal of recognition would not change anything. Poland would not become any more democratic as a result, the move would not hurt the Government - if anything the move would push Poland further towards the Soviet Camp - the only ones who would suffer would be the Polish people.

Bliss Lane was so at odds with his Government's policy towards Poland that he felt obliged to resign his position. In his resignation letter of 21st March, 1947, he wrote to President Trueman:

"As you know, these elections were not 'free and unfettered' as the Polish Provisional Government of National Unity had previously pledged, in keeping with the Yalta and Potsdam agreements. Quite the contrary, the pre-election period was characterised by coercion, intimidation and violence - thus rendering the election a farce and indicating on the part of the Polish Government a cynical disregard of its international obligations.

Under the circumstances I feel that I can do far more for the cause of the relations between the peoples of the United States and Poland if I should revert to the status of a private citizen and thus be enabled to speak and write openly, without being hampered by diplomatic convention, regarding the present tragedy of Poland." [53]

Protesting was all that was left with regards to Poland. At the first sitting of the Sejm, the Polish Parliament, on the 4th February, 1947, there was a sharp protest from the PSL:

"From the side of the PSL every effort was made to ensure the elections were clean and that they could be carried out peacefully. The responsibility for breaking the commitments given to the nation that the elections would be 'free and unfettered' lies solely with the parties.

We have protested against all aspects of the election and are aiming to have the election declared as invalid across the whole country." [54]

This last comment, according to the stenographic record, led to "merriment" in the chamber. The 'victors' in the election did not take such words seriously after all they, like Stalin, knew that there would be no conflict over Poland. The West would do nothing and the PSL were already on the political sidelines. However, for public consumption the Communists maintained the fiction that the elections had been a true expression of the people's will. The verbatim record of the 19th Sitting on 23rd June, 1947,

records one Bloc delegate:

"Every word of Delegate Mikolajczyk brings a stream of fury on account of losing the election. The last election held in Poland was free from reactionary pressure and that is why the result was as it was and no other. (Applause. Delegate Mikolajczyk: But it was not free from the pressure of rifles. Voice from the PSL benches: nor was it free from the pressure of the UB.) The elections were carried out in accordance with the principles of fair voting." [55]

Another delegate during the next day's sitting continued:

"The nation, in voting against you [the PSL] were voting against Anders, Komorowski, Sosnkowski and Mikolajczyk, they were voting against another twenty years Government of Endecja, Sanacja and Piast Party politics. That is why it is the people who are the victors of the elections." [56]

The historians of "People's" Poland also turned this blatant lie into an official truth. According to Jozef Szaflik's "Historia Polski" the election would prove whether the voters would choose social and economic reform or whether they would be "lured by the demagogue slogans of the PSL based as they were on the support of reactionaries." [57] The fiction was maintained by the Communists as it added legitimacy to their authority, historians in the West preferred to see the Provisional Government and the elections in Poland for what they were:

"Soviet support was necessary in this case to allow the Communists to hold onto positions they had already won. It can be asserted that in Poland the break-up of the coalition in 1947 was already guaranteed in 1945 and the coalition itself was never anything but a trick." [58]

For the Polish Armed Forces in the West who were desperately watching events unfold in Poland the prospect of return seemed more and more remote. Those who were concerned with the eventual repatriation of the Poles favoured a more optimistic view on the situation. Cavendish-Bentinck, in a secret cipher to the Foreign Office of 14th January, 1946, discussed his conversation with Mikolajczyk who had said that probably 80% of Anders' troops and a similar number from Germany and the UK would return to Poland in the Spring of 1946. According to Mikolajczyk the Officer Corps had...:

"...overreached themselves in the propaganda against returning, and that a number of men from these forces who had visited this country have returned with reports showing that whilst conditions are far from satisfactory they are not as bad as has been depicted." [59]

From Mikolajczyk’s various declarations and conversations before his return to Poland and then prior to the election it would appear that he spent much of his time trying to play down events in Poland and to present a picture that was decidedly unrealistic. In November of 1945 the Foreign Office sent a report of one of Mikolajczyk’s conversations that, no doubt, he went on to regret.

"M. Mikolajczyk said that the country was settling down and he alleged as proof of this that 95% of the Underground Army had emerged from the Maquis, and that casualties in the operations against the underground army which had at one time, I understand him to say, reached the enormous figure of 15,000 a month on each side had ceased. The battle for political freedom was being won. The Communists were no longer able to put down the other political parties except by force, which. they would now hesitate to use. [...]

M. Mikolajczyk said that the withdrawal of Russian troops was going fairly well and he thought that the majority of what he called field units had departed or were departing. Leaving only administrative, supply and L. of C. [lines of communication] personnel. [...] He regarded the recent arrangements for stationing a special Russian force in each area of Poland to mop up Red Army stragglers and looters as valuable and deplored its having been represented in some quarters as a new Russian occupation." [60]

It is little wonder that the British dismissed the fears and warnings of people like Anders as so much anti-Soviet propaganda when such an internationally respected politician as Mikolajczyk was going around sending contradictory and misleading messages that things in Poland were not as bad as was being made out.

Much was made at the time of Poles being shipped out to Soviet prisons, but again, this could be played down as scare mongering. Professor Frank Savory, the Ulster Unionist MP for Belfast University who did so much to increase awareness of the Polish cause, was equally dismissed when he broached the matter in the Commons. Savory argued that since 40% of the Polish Armed Forces had escaped from Soviet camps once before it seemed highly unlikely that they would return to Poland under the conditions that prevailed at the time. The Government spokesman, as reported in "The Times", responded:

"In regard to concentration camps, I know the hon. gentleman comes from a sister Island which is in the habit of looking backwards. (Laughter) May I suggest that we all look forward in this problem ? (Cheers)." [61]

General Anders, the bete noire of the Foreign Office, in an interview with "The Times" of October 23rd, 1946, stated that many of the Polish troops who had volunteered for return had also ended up in Soviet concentration camps. Hankey's letter from the Foreign Office to Brig. Pyeman at the War Office expresses the real reason why talk of prisons should be played down:

"I believe it is true that some of the men of the Polish Second Corps have got into concentration camps in Poland and it is also true that the Russians control the security police. All the same I do not believe any have got into specifically Russian concentration camps in Poland (if there are any) or that any have found their way into Russian concentration camps in Russia.

Might we ask you to telegraph to Italy and ask General Anders for his evidence. If it is true that these chaps are being sent to Russian concentration camps then we should be glad to know that it is so. If there is no evidence of that, however, then I do think we should discourage Polish Generals under our command from making statements which are calculated to cause alarm and despondency among those who wish to return." [62]

By causing 'alarm and despondency' among possible repatriates the flow back to Poland might dry up altogether, the last thing that the Government wanted. Every effort had to be made to get the Poles to go back to Poland and talk of camps did not help.

During the Foreign Affairs debate on the 22nd November, 1945, one MP who had just returned from a visit to Poland declared:

"I am authorised to say from the President of Poland that those Poles in the Polish Army in this country who return, will not only be given full civic rights but that no recrimination, in any shape or form, will be visited upon them because of anything they may have done in the past." [63]

These fine words, largely for the consumption of the Poles, were not matched by the deeds of the Warsaw authorities.

A report from Major Irwin, a War Office representative who had been attached to repatriation duties in Poland, had reached Hankey and the contents were less than glowing in its appreciation. According to Irwin the Poles were turned loose to fend for themselves with only a railway ticket; there had been no grants of land as had been suggested by Warsaw. The officers did not even get that. Their treatment was described as being worse than that for displaced persons. The officers had to undergo interrogation by Soviet Officers with the ever present threat of deportation to Siberia.

Hankey, who was seeking confirmation from Cavendish-Bentinck in Warsaw, wrote:

"...You will agree that it sounds pretty grim. Do you think that the treatment those Poles are receiving is in accordance with what the Polish Provisional Government promised, viz. equal treatment with those from the East?" [64]

The Polish security apparatus, alongside the NKVD, was busy arresting thousands of Poles and putting them in to the concentration camps of whose existence there was such a question in the West. Professor Savory in the Commons, on February 20th, 1946, tried to alert the Government to what was happening.

"I have here extracts from the correspondent of the Associated Press in Warsaw. I have made inquiries and have been told by an American friend that this Mr Larry Allen is one of their most respected and esteemed correspondents. This is his dispatch on 5th February: 'Authoritative sources reported today a new drive by Polish secret police whose net has swept an estimated 75,000 to 100,000 persons into prison. Official accounts of Police activity were not available and Brigadier General Stanislas Radkiewicz' - that is to say the Minister of Security '- has repeatedly refused to see journalists. Newspaper reports are censored and all incoming and outgoing messages are scrutinised by the military.'" [65]

While the Foreign Office could ignore Anders and his fellow officers as being avidly anti-Soviet, and therefore his opinions were biased - Military Intelligence sent the following assessment of Anders to the FO:

"General ANDERS and his country, especially his social class have suffered heavily at Russian hands, and it is not unnatural that he should feel strongly about RUSSIA at the present time. Evidence at our disposal, which is admittedly very limited, does not support his conclusions that Russian policy is fundamentally Imperialist and abetted by subversive use of the Communist parties in the democratic states." [66]

The views of independent outsiders could not be dismissed as easily as the MI branch dismissed Anders. As the information from Poland began to leak through to Whitehall so the seeds of doubt began to be sown.

During the preparation of Bevin's 'Keynote' text the second paragraph was heavily amended in light of the new information coming out of Poland and the growing lack of faith in the good will of the Warsaw Poles in the statement which they attached. The text ran:

"The Government regard this statement as satisfactory. [They are satisfied that it represents the firm policy of the Polish Provisional Government and that that Government will abide by the detailed assurances it contains.]" [67]

The highlighted passage was removed from the text by the Permanent Under Secretary of State, Hankey's immediate superior, Christopher Warner with a margined minute: "? Omit: I am far from sure. CFAW". Although the Foreign Office was 'far from sure' that the Poles would be safe returning to Poland they still advised them "to return to Poland of their own free will."

In a prepared answer to a question in the Commons, on the 7th December, 1946, the full Government position was laid out.

"Although we are watching for any confirmation of an unsatisfactory reception for repatriates, we do not want to discourage members of the Polish Armed Forces from returning home by giving grounds for anxiety based on unconfirmed rumours." [68]

There was also a line that the treatment was "In the main satisfactory" but this was removed by Hankey. In an answer to a supplementary question it was said that the...:

"...precise degree of assistance given to returned Polish Soldiers in Poland is, of course, a matter for the Polish Provisional Government."

This was a clear abrogation of all the responsibilities that Britain as a 'Great Power' had taken upon itself at Yalta and Potsdam. The message the Foreign Office were sending to the Polish troops was that the Poles should go back to Poland but their treatment there was not an issue that could be of concern to the British Government. The message did not inspire confidence among the Poles - on the one hand the British were telling the Poles that is was safe for them to return to Poland yet Bevin had felt compelled to publicly guarantee their safety, but was also put in the position of having to say that there was little that could be done if the safety of the returnees was threatened.

One WREN, Jessie Bradnum, who was engaged to a Pole wrote to the Foreign Office on this very point:

"As an ardent trade unionist (Railway Clerks Assoc.) and a member of the Labour Party, I should very much appreciate your assurance that the Government will satisfy itself that all members of the Russian secret police are removed from Poland, before our Polish allies return to settle down. Furthermore can we assume that if Polish nationals return now they will receive the protection of HM Government should further political troubles arise." [69]

The Foreign Office reply was that "...the protection of His Majesty's Government cannot be extended to

individual Poles in Poland."

The approach of the Government to events in Poland did change with time. Count Raczynski, in his published diary, writes of this change in attitude, in particular as it related to British POWs who had been freed by the Red Army and then robbed by the Soviet soldiers.

"I saw the effect of this at the Foreign Office. Till recently, many of our reliable reports had been met with scepticism because they conflicted with official hopes and wishes. Doubts were expressed to us as to whether we genuinely represented the Polish nation, whether the Lublin regime was really hated by almost all Poles, and whether the country's sufferings were so great as had been made out. These questions are now no longer asked." [70]

Although he overestimates the change in London, writing as the ambassador was in June, 1945, the mood change was certainly beginning.

In response to a request from the National Assistance Board for more 'active propaganda' to encourage men to return to Poland, Hankey of the FO wrote to Mr Whetmath of the NAB:

"As you know, the Foreign Secretary has, on numerous occasions made clear his view that it is the duty of all Poles who feel able to do so to return to Poland, in order to take their part in the work of national reconstruction. I do not think that we can go any further than this. The fact is that conditions in Poland are thoroughly unsatisfactory, a steady drive towards Communisation is underway, and there have been many arrests of independent socialists and others who wish the tendency to be resisted. In the circumstances, we really could not accept the moral responsibility of advising men to go back." [71]

Hankey's position in 1947 was considerably changed from the declaration of Bevin in the Commons, August 20th, 1945:

"...I inquired from Marshal Stalin whether the Soviet troops were to be withdrawn, and I was assured that they would be, with the exception of a small number required to maintain the communications necessary for the Soviet troops in Germany. That is not unreasonable. There is also the question of the presence of secret police in Poland. That still needs clearing up, but, with these assurances, I would urge Poles overseas, both military and civilian, to go back to their country and assume their responsibilities in building a new Poland. They will render a far greater service there than they can do from outside." [72]

For many of the Poles this change in attitude came too late. Many of the troops had been convinced by the early declarations of the British and Polish Provisional Governments, and many had fallen victim to the 'question of the presence of the secret police' that had yet to be cleared up.

Paul Tabori, while on a visit to Warsaw in 1964, met a taxi driver "who cursed his own stupidity" for having returned to Poland. The driver had formerly been in the Anders Army but after the war had gone back to marry his pre-war girlfriend and quickly found himself in a Communist prison for having "spent the war at the wrong point of the compass". [73]

Jan Podoski was another repatriate who had cause to regret his actions. [74] An engineer before the war, he had worked for the Polish subsidiary of the Bradford based English Electric Company. Although he spent the first years after the war in the same position as many other Poles - trying to decided whether to return or not, it was a letter from the rector of the Faculty of Electrical Engineering at the Warsaw Polytechnic offering him a post lecturing that finally won him over to return. On July 7th, 1947, Podoski returned to Poland on a Polish freighter only to find himself the subject of an investigation by the security services. When the case went to trial he was sentenced to 8 years - a victory according to Podoski's defence lawyer considering the charges were spying and conspiracy. He was pardoned in 1989 by the post-Communist authorities.

The fact that the Polish Security Service - the UB, were arresting Poles on spurious charges was known to the British. In a confidential letter from Hankey of the FO to Lt. Col. Fitzgeorge-Balfour of the War Office he wrote on the subject of offering guarantees of safety to repatriates, on the 27th May, 1947, that: "The Warsaw Government is not trustworthy and if they were to break the guarantee, we should have no means of executing ours." [75]

Reports of conditions continued to reach the Foreign Office from both partisan and impartial sources. The Communists claimed that all talk of repression was part of the 'fascist' propaganda by Anders and his 'band of reactionaries'. On the other hand the claims of the exiles could also be played down. What was more difficult to ignore were the reports from independent sources such as Britons who had been to visit Poland and versions from the staff at the British embassy. A memorandum was sent to the Foreign Office by Sir Waldron Smithers MP in June, 1946, claiming that as many as 50,000 Poles had been imprisoned by the Communists. The report further stated that:

"...the new trend in British policy towards the Warsaw regime prevents official circles from taking sufficient interest in these people's fate to investigate the matter with the Soviet Government." [76]

Hankey's file minute read:

"I am sorry to say this deplorable story is likely to be true. I collected a good deal of information on the subject while in Warsaw, but the figure of 50,000 is probably much too high."

Hankey had a great deal of experience with Polish issues; before the War he the Second Secretary in Warsaw under Sir William Kennard, and he had been Acting Councillor under Cavendish-Bentinck when recognition had been given to Warsaw in 1945. There were few in the Foreign Office as qualified as Hankey to discuss events in Poland but even he underestimated the full extent of the internecine struggle that was going on in Poland.

Cavendish-Bentinck had presented a report to the FO in February, 1946, after a conversation with Dr Litwin, Warsaw's Minister of Health. While discussing the widespread typhus epidemic in Polish prisons the UK ambassador had come to the conclusion that there may have been some 40,000 political prisoners in Poland. [77] But even with the increased intelligence that was coming out of Poland the fact remained that the more that was known about events there, the less it would encourage Poles to return. In a Foreign Office letter to Hugh Dalton, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, the problem of Anders inciting anti-Communist propaganda was again causing friction:

"...According to the "Times" of the 25th October, he has just claimed, in a speech made in Italy that, of those Poles who have opted to return to Poland, many have found their way into Russian Concentration camps. We think that this is an exaggeration of the truth but, even if it were true, it would not be at all the sort of thing we wanted said publicly, since it is just the sort of thing that discourages Poles from going back to Poland." [78]

The idea was that any public disclosure of what was happening in Poland should be covered-up to ensure that as many Poles as possible returned - even if prison did await many of them. It was a hopeless task to keep conditions in Poland a secret, although not for want of trying. The Poles refused to be convinced. As one British spouse wrote to Bevin:

"The position being as it is would you yourself return to that country were it yours ? I am sure not.

I am the Scottish wife of a Polish soldier and I know what Poland means to him let alone his compatriots.

I assure you they would return to a man Mr Bevin, if only you'd give them that guarantee of safety which they so badly need. The whole question rests on the removal of the Russian Gestapo." [79]

Mrs Nowak makes a fair point that was difficult to answer by the Foreign Office. The British Government could not and would not guarantee the safety of the Poles returning to Poland; there was serious doubt about the safety of those returning to Poland and still they were encouraging more to go back.

One of the more distressing aspects of life in post-war Poland that drew criticism from the outside world was a resurgence of anti-Semitism that culminated in the Kielce pogrom on July 4th, 1946. As 40 Jews were murdered by local peasants the Government blamed right wing extremists while the more moderate politicians of the PSL blamed Government provocation. Emil Sommerstein, a Zionist, gives one possible explanation for the phenomenon:

"Given the numerical weakness of the Party [PPR] and the traditionally high percentage of Jews in the leadership of the Polish Communist movement, it is not surprising that they became highly visible," [80]

Despite the sufferings of the Polish Jews under the Nazis they found themselves being attacked after the war by some Poles who saw them as the embodiment of all that was wrong with Poland. Underground organisations like the NSZ [National Armed Forces], had fought against the Germans and the Communists with equal vigour and now looked at the Jews as part of a conspiracy that drew Poland towards Moscow. The NSZ newsletter "Szczerbiec", named after the coronation sword of the Polish Kings, still speaks of the "Zydokomuna" - the 'Jewish-Bolshevik conspiracy' that the Nazis were so fond of talking about. The former Chief-of-Staff of the NSZ, Stanislaw Zochowski, highlighted a top secret order from the Minister of Public Security, Stanislaw Radkiewicz, to UB posts in Poland:

"Therefore we recommend to all directors of UB posts to prepare actions with the utmost secrecy to liquidate all opposition activists but they must be carried out as though they were done by bands of reactionaries." [81]

The Polish Government while instigating many of the most serious incidents in Poland then used them to denounce the NSZ and the antigovernment opposition in general and use them as a pretext for extermination.

Everyone in Poland, and the Poles in the West, knew what was going on in Poland - the Communists, however, did not talk about it. It was only after many years that it became possible to review the post-war years with anything like an accurate picture. Stefan Staszewski, the former Minister of Agriculture, once wrote:

"There is nothing to compare with the period of violence, cruelty and lawlessness that Poland experienced in 1944-47. Not thousands but tens of thousands of people were killed then. The official trials that were organised after 1949 were merely an epilogue to the liquidation of the wartime resistance, of activists, of independent parties, and of independent thought in general." [82]

During the period of de-Stalinisation in Poland, as in the Soviet Union after Khrushchev's 'secret speech', a wealth of information began to emerge as to what had been going on in the Communist world. Leon Wudzki, in a speech to the Central Committee of the Polish United Workers Party [PZPR] made on the 20th October, 1956, reflected on the horrors that had just passed:

"...People who were caught in the streets and released after seven days of interrogation, unfit to live. These people had to be taken to lunatic asylums. Others sought refuge in the asylums to avoid the security police. Men in panic, even honest men, were fleeing abroad to escape our system.... The whole city knew that people were being murdered, the whole city knew that there were cells in which people were kept for three weeks standing in excrement... cold water was poured on people who were left in the cold to freeze...." [83]

But it was not only the Polish Security forces that were carrying out mass arrests, there was also the Soviet Army and Soviet Secret Police [NKVD] in Poland acting very much as a law unto itself. Officially the Soviet elements did not exist in Poland. After all had not Bierut told Churchill at Potsdam that "generally speaking, the whole Russian Army was leaving". [84] According to Bierut "The NKVD played no role in Poland". This, of course, was far from the truth. From the first days of Soviet 'liberation' many Poles had begun to disappear - mostly soldiers of the Home Army [AK]. In August 1944 the AK Commander of the Lublin area contacted AKHQ:

"The NKVD is carrying out mass arrests of Home Army Soldiers throughout the area. They are put into Majdanek. The staffs of the 3rd and 9th infantry divisions and General 'Halka' are there, about 200 officers and 2,500 privates. New isolated camps in the Kraskow Wlodawski marshes are being organised... the Majdanek officers and some of the men were deported to Russia on 23 August." [85]

Another AK source reported that from the 6th November, 1944, there had been mass arrests in the Polish People's Army of officers who had confessed to having belonged to the AK. Some 600 of these were being held in a camp at Skrobow, guarded by 900 Soviet security guards, apparently dressed in Polish uniforms. [86] On the 6th March, 1945, the AK Commander of the Lwow district contacted the AKHQ that the Soviet authorities were systematically removing Poles from Eastern Malopolska, and in particular from Lwow.

According to 'Winnica', who wrote the report, some 6,000 Poles had been arrested in Lwow in one week of January, this number included University professors, priests, students, workers from the gasworks and power station. The usual pretext for arrest was collaboration with the Germans. [87]

Another report to AKHQ came from Stefan Korbonski in April, 1945. He reported that the greatest action of pacification by the Red Army was in the Turobina area. He wrote that units which had left Lublin going westwards had now returned and were in the process of rounding up more Poles. In Lublin Castle alone there were about 8,000 prisoners - there had also been some 99 death sentences carried out. He also wrote of the Soviet concentration camp in Skrobow which was exclusively for AK soldiers. [88]

The OC Bialystok region, 'Mscislaw', a man who, according to Korbonski, was "worshipped" in the area [89], ciphered AKHQ that the NKVD had deported more Polish intellectuals in the few months previous to May, 1945, than the Germans had done in four years of occupation. The Poles in the city's prisons were living and dying in unheard of squalor. After interrogation the Poles were then deported to Siberia. [90]

'Mscislaw' - Colonel Wladyslaw Liniarski’s report of 12th May, ten days after the one cited above, gave an even more disturbing picture of what happened to the Poles after the NKVD had finished questioning them. The NKVD took the Poles, former soldiers of the AK, out to the forest and shot them and in order to keep the executions secret the bodies were then buried in the mass graves of the victims murdered by the Gestapo in 1944. [91]