CONCLUSION

At the end of November, 1946, the No.5 (Polish) Field Hospital left Italy for the last time and was moved to Britain where it reopened at Barns Farm Camp, Storrington, West Sussex. In June, 1948, it was renamed "PRC General Hospital - Storrington" and remained open until the complete demobilisation of the Polish Army.

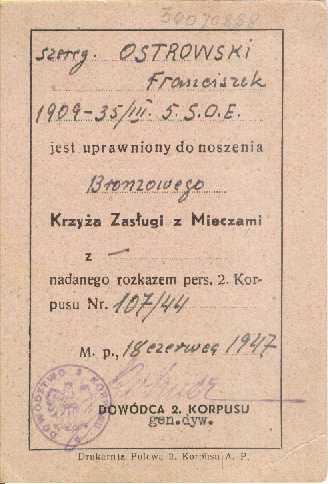

Franciszek Ostrowski officially left the Polish Army on the 1st of April, 1947, to join up with the Polish Resettlement Corps. He continued working at the hospital until he began civilian work on the 10th of September, 1948, with the Redland Brick Company near Horsham in West Sussex. Following the terms of the Resettlement Act he was placed on the "Class W(T) Reserve" for the remainder of his two year contract with the PRC before being discharged on the 1st of April, 1949. It had indeed been a long war.

He, like every Polish soldier, sailor and airman had made the same decision about his future.

Franciszek Ostrowski officially left the Polish Army on the 1st of April, 1947, to join up with the Polish Resettlement Corps. He continued working at the hospital until he began civilian work on the 10th of September, 1948, with the Redland Brick Company near Horsham in West Sussex. Following the terms of the Resettlement Act he was placed on the "Class W(T) Reserve" for the remainder of his two year contract with the PRC before being discharged on the 1st of April, 1949. It had indeed been a long war.

He, like every Polish soldier, sailor and airman had made the same decision about his future.

To return or not to return depended on three basic considerations about Poland after the war. The first consideration to be made was a moral one. To return to a Poland under the Communists was viewed by many Poles as a tacit vote of confidence for the new regime. This was an unfair judgement on the intentions of most but it was a view that also influenced many. Peer pressure and the prejudice of superior officers led to an association of return to Poland with treason and betrayal to the cause of an independent Poland.

The second consideration that was made was of a more practical nature - how to survive in post-war Poland. The most obvious manifestation of this fear was the security situation. The rank and file of the Polish Armed Forces had for years been propagandized about the nature of the Soviet Union by their officers while many of them had had first-hand dealings with the Red Army from 1939 onwards, so they were under no illusions as to what it meant to be a 'class enemy' to Communism. Fear was a key element in deciding whether to return or not. Even if some Poles did not fear the new regime they knew that life in Poland would not be easy. The devastation of the war had left the country a ruin. What the Germans had not destroyed during the occupation had been demolished by the sweep of the Red Army 'liberating' Poland. The chronic housing shortage in Poland and the poor living and working conditions had their impact on willingness to return yet for some even this was more preferable than living the life of an exile in Britain with its post-war austerity and, seemingly endless, rain.

The third consideration that should not be overlooked was a geographical one - despite the calls of many British Labour Party supporters that the Poles should return "home", many did not have homes to return to. Vast tracts of Polish land had been lost to the Soviet Union and the Poles who had once lived in the eastern part of Poland knew that if they returned to their homes east of the Curzon Line they would become citizens of the Soviet Union - a prospect that very few relished. The other option was to start a new life in the land that had been 'recovered' from Germany. Upper Silesia and East Prussia were now part of Poland and the question arose of just where did the Poles prefer to start a new life - in Britain with its possibility of later moves to Canada or the USA, or in a Poland dominated by the Red Army slipping into a dictatorship backed by the guns of the secret police.

The fact that so many Poles did not return to Poland is not, given the situation at the time, so much of a surprise. What is more striking is the large number who did return. 105,000 Poles, over 42% of the total number, returned to Poland. A small minority were prepared to return to their homes in Poland's eastern Kresy to live as Soviet citizens - their ultimate fate has yet to be adequately recorded. Some who had homes and families to return to went back to Poland to help in, as Bevin put it, the "arduous task of reconstructing the country and making good the devastation caused by the war". Many who were prepared to heed Bevin's words and risk the vengeance of the Communists went to Poland to help populate the newly acquired land in the West of Poland.

The dilemma that divided the Polish Armed Forces is not an easy one to define. Although the criteria can be broadly categorized into groups, there were as many reasons to return or not as there were soldiers. After half a century it is as difficult as it is pointless to argue over who made the right decision. The exiles quickly settled into British life - according to John Keegan they became the "most successful immigrant community ever absorbed into British life" and, he continues, the fires of exile have "sunk into embers" [1] yet the Poles were foreigners - to many they were "bloody foreigners" - in a country that remained largely alien to them. Bitterness and cynicism have stood the test of time.

In Poland the Poles who had fought in the West had to suffer at the hands of a regime that had no popular legitimacy and abused its power to persecute its own citizens, yet they could grow old in the knowledge that they were in their country and among their people. The reconstruction of Poland after the devastation of war is an achievement of which Poles in Poland can justly be proud - a pride now shared by the men who fought at Cassino, in the Battle of Britain and the Battle of the Atlantic.