Bruce DePalma's experiments of the 1970's qualify him as America's 20th Century Galileo because he and Ed Delvers documented that a spinning object falls faster than a non-spinning object, and rotating and precessing gyro assemblies lose weight and their inertia in is changed, polarized along axes of rotation. This is one of the earlier newspaper articles about their work before the built the n-Machine electric generator to extract electricity from the energy field in space they discovered as the "rotational force field" in the early 1970's, where the n-Machine was first built and tested in Santa Barbara California under auspices of the Sunburst Community, why it was also known as the S-Machine. I met DePalma and Delvers in May 1979 and collaborated with them to get more press and university exposure of their work during the 1980's.

--------begin transcribed articles

[photo, not shown here, Bruce DePalma in his living room

in background with two "force machines" (precessable

counter-rotatable flywheel assemblies) hanging from the

ceiling by ropes to each of their four corners; captioned:]

Bruce DePalma with two of his machines, which he claims

prove the existence of the rotation force field

The Sunday Times Advertiser

Trenton, N.J.

GAZETTE

Sunday, January 11, 1976

Page E 1

Princeton doesn't believe in Bruce DePalma

But then, of course, Bruce doesn't believe in Einstein

By Eric Sauter

Staff Writer

Bruce DePalma, a 40-year-old student of life, knows

he is right. He gets confirmation of this fact almost

daily. It comes from everywhere -- Germany, England,

Arizona. It comes from ex-scientists, ex-academicians,

dissatisfied physicists and amateur inventors. It comes

in the form of privately printed books and articles,

Xerox copies of patents for antigravity devices, cryptic

letters with apocalyptic overtones and still more pages

filled with unsigned accusations against Them -- the

scientific and academic establishment. DePalma has

files and files of these confirmations in his 55-acre,

18th century farmhouse estate in Bedminster, Pa.,

just a few miles north of Doylestown.

They come, he says, from the Physics Underground, a

conglomeration so vast, so formless that he doesn't

even know how large it really is. Except, he says, it is

everywhere. Everywhere! In rooms and basements and

attics these faceless, sometimes nameless people are

working, tinkering, theorizing toward the one goal that

Bruce DePalma has taken upon his own shoulders.

Bruce DePalma wants to save the world from itself.

"This is," he says quietly, hands moving like tiny bird's

wings to shape the importance of his statement, "the

biggest story of the 20th century."

He is sitting in the dining room at the large wooden

table. His thinning hair is combed down over one side

of his forehead. He is wearing a blue and red Harvard

T-shirt, brown jeans and baby blue track shoes. He looks

like an aging undergraduate or perhaps one of those

resident advisors in an Ivy League dormitory, just passing

his prime. Above all, he is clean and neat.

"I thought I'd tell you a story," he says, "just like the ancient

mariner sits down to tell his tale." He pauses. He rubs his

hands. A smile moves across his boyish face like a creature

with a mind of its own.

"This discovery of mine refutes Einstein's theory. What I

mean is, this is a breakthrough in physics. Let me say first

that people have vibrations. You are not put off by my saying

that are you? You know people give off vibrations, you've felt

them. What we have done is to establish the physical validity

of these things. If scientists would only verify my experiments

it would change all the theories.

What DePalma's experiments have proven, at least to his

satisfaction, is that if you rotate an object, you radically

alter certain physical properties of that object: both its

mass and its inertia. Rotation, according to DePalma, also

produces a force field, specifically around the main axis

of the rotating object. He says he has measured this force

field.

What this means to DePalma is unlimited in its wonder and

universal in its scope. He says that the rotation phenomenon

and its force field can be used in a number of different ways

-- the vibrations from the force field can be a perfect cure

for cancer; the rotating effect can be harnessed for the creation

of an antigravity device and a 200-mile-per-gallon automobile.

He goes on and on. It could eventually produce a world free

from hunger, war and poverty. In other words, a perfect world.

All of this because Bruce DePalma says he has made certain

discoveries so simple that physicists for the last 50 years have

not even thought of them.

"You know," he says calmly, "we have tried to publish papers

on this discovery since 1971." Four years we've tried. After

getting turned down by all these magazines we learned that

the physics department at Princeton was blocking their

publication."

He gets angry. "Those dimwits over at Princeton are such fools.

They think they can use their authority like Nixon, but we know

what plays in the Oval Office may not play in Peoria or in Trenton."

He looks thoughtfully across the table, secure in his status as

another victim.

DePalma turns to Ed Delvers, his 25-year-old assistant, who has

been with DePalma since his days at MIT five years ago. "Ed," he

says, "would you cook something for me, just put something on

a plate." Ed begins to go into the kitchen but DePalma changes

his mind. It is too early to eat. Ed returns quietly to the table.

Bruce DePalma is currently locked in his life and death struggle

with the physics department of Princeton, specifically with

Dr. John Archibald Wheeler, author of a widely used text on

gravitation and relativity and considered by many to be one

of the leading experts in the field.

"Wheeler even said that all his thoughts on gravity will be

shattered if my experiment is correct, and there he sits

with his dead hand on the wheel. In our meeting they

even said that my simple inertia experiment was worth

a Nobel Prize. Yes, they said that."

The meeting DePalma is talking about took place on Dec. 5

at Jadwin Hall on the Princeton campus. Present were

Bruce DePalma, Ed Delvers, John A. Wheeler, and Dr. Frank

Shoemaker, another Princeton physics professor.

"You see," DePalma said, "I'm a pretty innocent guy. But

the CIA and FBI and Watergate finally convinced me that

intelligent men could commit sin. It also occurred to me

that my discovery would discredit their (Princeton's) position

in Washington and their $215 million grant."

That $215 million grant is for the construction of a prototype

fusion reactor to be built at Princeton. DePalma claims that

it won't work simply because they have not taken his discovery

of the effect of rotation into account.

The meeting finally took place after DePalma wrote a letter

to William Bowen, the university president, delineating his

problems with certain members of the physics department

who were reluctant to give him the time of day. He got a

limited response, a short note from the president's secretary

pleading Bowen's ignorance of physics and washing his hands

of the whole problem.

DePalma then wrote a second letter telling Bowen he was

about to squelch their prospect for the $215 million. Did

he actually threaten them?

"Of course," he said, "The whole reason I did this is because

I'm worried, I'm concerned. I really care. Look, we have all

these problems and they're not doing anything about them.

After the second letter Wheeler called me and asked, 'What

do you want?' So I told him. I said I wanted to solve the energy

crisis."

Bruce DePalma's awareness of his unique position in the universe

came about in the spring of 1971. He was fed up with academia,

fed up with everything. "When I was at MIT I tried harder than

the president to make MIT work but the faculty resented my

attempts to build up school spirit." So he headed west to California

with five of his students, followers he had collected from his

lecturing days in Cambridge. Ed Delvers was one of them.

DePalma has had a startling background. His father,

Dr. Anthony F. DePalma, now retired and living in

Florida, was the head of the department of Orthopedic

Surgery at the New Jersey Medical School in Newark. One

of his brothers, Barton, is a West Coast painter of some

merit and head of the art department at Foothill College,

Los Altos. His other brother, Brian, is a well known film

director whose latest film, interestingly enough, is called

"Obsession."

Even more interesting is the fact that all this information

appears on the front page of Bruce DePalma's resume.

DePalma graduated in 1953 from the Friend's Central

School, a private school for above average students in

Philadelphia. He won the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute

Gold Medal for excellence in math and physics and entered

MIT in 1953.

He had a stellar career at MIT. His freshman year he won

a regional award for a student paper he wrote on low

distortion amplifiers which was eventually published in

"Audio Engineering". During his junior year he left MIT

to work as a consultant for the Dyna Company of Philadelphia,

working again with audio amplifiers. He also attended the

graduate school of Temple University on a part-time basis,

taking courses in physics and thermodynamics.

He received a B.S. from MIT in 1958 in Electronic Engineering

and began working for various electronics corporations,

moving from one to another during the boom years of the

electronics industry.

In December of 1963, DePalma settled down, taking a position

in the Physical Chemistry Group of the Polaroid Corporation,

Edwin Land's gigantic research company in Cambridge, Mass.

He also went back to MIT, not as a student but as an appointed

lecturer in photographic science, on the recommendation of

Dr. Harold Edgerton, a professor who was working with

photography, specifically strobe light pictures. They shared

a common passion for photography and had become friends.

Edgerton remembers DePalma as a "very imaginative young

man" who was fascinated with photography. "He was always

jumping around looking for new ideas," Edgerton said.

By the time he left Polaroid and MIT, DePalma was making

$40,000 and was able to afford a new Ferrari, a prized

possession that still sits, clean and in good condition, in

his front yard in Bedminster. He gives it a spin once every

two weeks or so to keep it in working order.

DePalma has been able to maintain the car and his extremely

comfortable lifestyle by donations. Since 1971, after he'd

come back from California broke, these donations have totaled

about $100,000. These gifts have come from various supporters

and students who believe in what he's doing.

He says he intends to pay it all back. "When my discovery pays

off, there's going to be a lot of money. I intend to pay back

$100 for every $1 I've been given."

Over the last 20 years DePalma has moved back and forth through

experiments on sound, underwater communication, the effects

of underwater nuclear blasts, laser beams, X-ray photography

and three dimensional motion picture film, a process he perfected

at Polaroid only to have it turned down by Land, who was engrossed

in the development of the SX-70 camera.

Perhaps put off by Land's rejection of his project, in 1970 he left

and went to California. By the time he got there, the battles of

the 1960's were already dead and gone. No matter. Bruce DePalma

was thinking about the problems of peace.

The meeting at Princeton on December 5 was a disaster. It was so

incredible Bruce DePalma couldn't believe it. There he was, with

his most important experiment, an experiment so simple even a

child could comprehend it. His students, who had followed him

to California and back, who had supported him, they had seen it.

They believed it. But the Princeton physics department was not

impressed.

"They think they're such experts over there. We did the spinning

ball experiment and they said, 'Our eyes aren't that good.' They

didn't think they could see it."

"After we did it," DePalma said.

"They fell silent," Ed said.

"They went into catatonic paralysis," DePalma said. "So I told

Wheeler. The next time I see you, Doctor, it will be in front

of the camera and the lights. I don't want anything to do with

them any more. I even wrote a letter to Dicke (another Princeton

professor who refuses to talk to DePalma) telling him to resign

before a very unpleasant situation develops."

The experiment is quite simple. DePalma takes two steel ball

bearings, spins one while the other remains stable and throws

them in the air. The spinning ball goes higher than the stable

one. DePalma claims this refutes Einstein's theory of relativity.

DePalma became enraged at the physicists' attitude towards

him, particularly at Wheeler, who he has singled out for his

most vicious criticism. "They treated me like I had no brains

at all," he said. He became emotional at the meeting and

started to yell at them.

Frank Shoemaker asked him to leave.

"I know I have no power myself," DePalma said, "I only have

the power other people confer on me. I will get invited to

Washington only after I generate a lot of publicity. To get

this against the ineptitude and stupidity I am facing I have

to be really clever."

"Ed," he said, "would you get me another glass of Sprite?"

Ed rises quickly and gets him another glass of Sprite.

"I'm not an outcast. I think of myself as a folk hero of

science. I have my students out here. I ride a motorcycle,

play the guitar, write poetry. I'm an interesting fellow.

I'm not an ordinary man. Extraordinary people do. You

have to accentuate your extraordinariness to make things

happen."

"Ed," he said, "could you bring me something to eat now?

Would you like something? No. All right. Ed?" But Ed was

already in the kitchen, dishing up the food.

"Our work," he said, "is being carried on by a number of

people all around the world. So what am I going to do

next? I'm going to start a clinic for the treatment of

cancer using vibrations like those of the spinning balls.

I'm going to raise money and heal people with these

radiations."

"You see," he said as Ed brought the plates into the

dining room, "I have no secrets. I'm naked in front of you."

Dr. Frank Shoemaker sits in his large office overlooking

a wide-open courtyard that is dominated by the big black

Calder sculpture in the middle. He is a medium-sized man

with short grey hair. It has a slight wave to it, reaching up

to the top of his head. He is wearing a red plaid shirt and

glasses. He laughs a lot.

"There's nothing like the theory of relativity to bring the

nuts out of the woodwork," he said. He is speaking about

Bruce DePalma.

"DePalma's approach is completely unprofessional," he said.

"A scientist doesn't set out to prove an idea right. He looks

for ways to prove it right or wrong, if you know what I mean."

But DePalma, Shoemaker went on, always finds something

in his experiments to prove his theory right.

At that Dec. 5 meeting, Shoemaker tried to explain away

DePalma's effects by saying they were simply "ordinary

effects" that DePalma had misinterpreted.

DePalma didn't want to hear it. "He flew off the handle,

started calling us names. I told him I was going to throw

him out of the building if he didn't control himself. He just

didn't want to hear that ordinary things were causing his

effects.

"DePalma's case is not that surprising. Many people construct

their lives around one thing. They develop this singlemindedness

of purpose. In that letter he wrote me, he sounded like a man

rebelling against authority."

The letter DePalma wrote to Shoemaker sounds as if it should

be read at the volume of a scream.

"I lost my interest," DePalma wrote, "in the viability of the

institution of the so-called 'science' you uphold when it became

clear you and the rest of you are incompetent and incapable of

receiving new information.

"I think it is clear that the energy crisis and other economic

and political woes of this country and the world at this time

is due to the activities of Professors like you and Dr. Dicke,

Dr. Wheeler and your ilk."

Dr. John Archibald Wheeler is more reluctant than Shoemaker

to speak his mind.

"I really hat to talk about it," Wheeler said, "I would be upset

if DePalma tried a scientific problem in the daily press. It

wouldn't be right to deal with the situation like this."

He doesn't know anything about DePalma's charges that he

and his colleagues tried to block the publication of DePalma's

articles. In fact, the question seems to confuse him. But what

bothers him is that DePalma hasn't done enough tests and the

ones he has done are simply not accurate enough.

"I don't see any substitution for tests," Wheeler said.

DePalma also showed his experiments to John Taylor, who

teaches physics at Bucks County Community College.

"I'm not sure if he has something or not," Taylor said, "I know

he didn't put sufficient effort into measuring it. He's got a

very fancy apparatus but something's out of line. Why doesn't

he have some experimental data? He tells me he doesn't

believe in statistics and that turns me off right there."

Another physicist who is familiar with DePalma's experiments

is Dr. Edward L. Purcell, a professor at Harvard.

"They told me about the experiments," Purcell said, "but they

weren't very good. They didn't show me anything. Similar

experiments have been done like this with far more accuracy."

But what about the spinning balls? "If there were any effect

like he says, we would have had gross problems with our

satellites. After all, they're spinning objects. Of course,

he says they're not spinning at the same rate as his, but

naturally he says that.

"A baseball spins," Purcell said. "If you throw a spinning object

in the air, of course there will be an effect. This isn't even

very interesting."

This grates on DePalma's nerves. Not very interesting? How

can they say that? He plays the guitar, he listens to rock

music. Wheeler and Purcell don't listen to rock music, do

they? Of course not. They are the dull ones.

"I want to tell people that they're sending their kids to these

people to be brainwashed," DePalma cried. "Until we get rid

of the theory of relativity no progress will be made and that

includes Wheeler and their ilk."

Shoemaker invited DePalma back to Princeton to test his

experiments on their equipment. DePalma declined. If they

were really interested, he said, they could do his experiments

all by themselves. They don't need him. He certainly does not

need them.

"I know what you wanted to do," DePalma said to the reporter,

"you wanted to destroy me. You had me in your pidgeonholes

and you wanted to get rid of me once and for all.

"But see," he goes on, "you're not going to do that now. I'm

going to be with you from now on. You think you can just go

back and forget this but every story you do from now on I'll

be in, because what I have will influence everything."

DePalma gets up from the table and walks into another room.

He comes back carrying a photograph. It is a black and white

picture of a young man sitting in a semi-lotus position. He has

a thin face and bright intelligent eyes.

It is one of DePalma's students who not long ago at a capsule

of cyanide and died.

He lays it in the middle of the table.

"He couldn't get rid of a lot of things," DePalma said pointing

to the picture. "He wanted a brother, he wanted the notion

of a brother so bad. But he just couldn't shed these attachments.

We were hurt by his death."

"I'm already starting. I'm getting rid of everything. I'm on the

road to attainment. Attainment is becoming, you see. It is a

continual process. I can see that your journey is almost at

an end. You fight it with everything you have but they always

to that just before the end. You're almost there, I can tell."

"You see," Ed Delvers said, "you won't be able to stop the

change. It will just happen to you."

"Right," Bruce DePalma said, "there's no way you can go about

looking for it. My discovery is the way we can make it possible

for everyone. I want my discovery to help people. I want it now.

You have to believe this. Don't you want this, too? Don't you

want peace and harmony, don't you want to drive 200 miles

on a gallon of gas. Why don't you just give in to this?"

---end article number one, same page starts second article:

(companion article about the spinning ball experiment)

[photo of trajectories of spinning vs non-spinning ball bearings,

black background, higher trajectory approximately 6-8 ball

diameters higher than lower trajectory, balls illuminated

against black background; photo not shown here, captioned:]

You have to watch the spinning balls

There are two experiments which DePalma claims prove his discoveries.

The main one, proving that rotating radically alters the physical

properties of an object, involves two spinning ball bearings.

A strobe flash of that experiment appears above.

DePalma writes: "We have discovered that the spinning or rotation

of objects changes their inertia. When a spinning object is dropped,

it falls faster than a non-spinning object because its inertia has been

reduced by the effect of rotation. Therefore, an object of given

weight will fall faster when it is spinning than when it is not spinning."

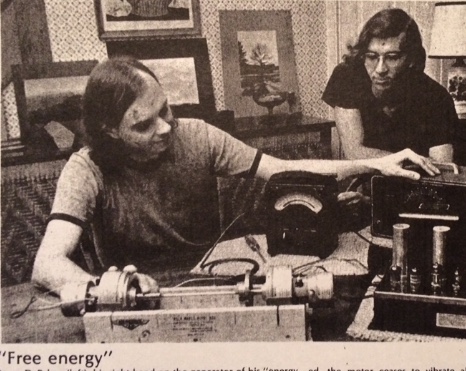

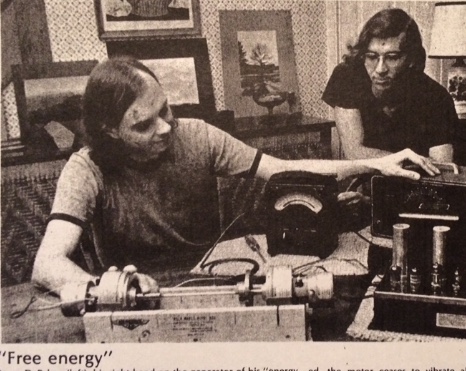

The device used to spin the ball bearing is a simple lathe machine

socket activated by a small, hand-held motor. The other ball

bearing, resting in a stable socket, sits next to it. After a

reasonable amount of spin is attained on the one ball, DePalma

throws them both in the air. The spinning ball goes about 5 per

cent higher than the stationary one, he says. He has strobe

photographs of this effect.

This effect, if it is what he says it is, goes against Newton's idea

of inertia, and Einstein's theories of gravitation, which says,

basically, that all objects, no matter what their mass, fall at

the same rate because their inertia (the tendency to remain

at rest when at rest and the tendency to remain in motion

when in motion) is constant.

The other experiment which, DePalma claims, proves the

existence of a rotation force field, is not quite so simple.

He places an Accutron watch above the axis of a 29-1/2-pound

flywheel spinning at 7,600 revolutions per minute. The Accutron

watch has a small tuning fork which sets the timekeeping rate

of the watch. The manufacturer claims that this tuning fork

will keep accurate time to within one minute a month.

The watch is separated from the flywheel by a magnetic shield

to eliminate any effects from motors driving the flywheel itself.

An electric clock is synchronized with the Accutron to compare

accuracy after exposure to the rotation force field of the flywheel.

According to the results of the test, with the flywheel spinning

at 7,600 rpm, and running steadily for 1,000 seconds (16-2/3 minutes),

the Accutron loses .9 seconds relative to the electronic clock, which,

DePalma claims, is not affected by the rotation force field. If this

actually happens, then the effect of the rotation force field has

greatly altered the Accutron's tuning fork. Compared to the

manufacturer's claim of loss for the watch, it means that the

watch would lose somewhere around a half an hour a month

if exposed to the force field that DePalma claims exists.

Rotation then, according to DePalma, affects the physical

properties of matter, changes the very things that physicists

have based their theories on for the last few decades.

"These theories," DePalma says, "are just a bunch of science

fiction." He says that they have neglected to take into

consideration his discovery of rotation and its effects on

the real physical properties of objects. DePalma claims

their theories don't work because his theory goes to the

very heart of the nature of things -- atoms -- which,

DePalma says, are also rotating objects.

--- Eric Sauter

-------end articles