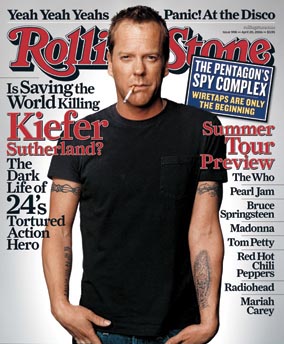

Kiefer Sutherland: Heart of Darkness

Kiefer Sutherland is quite looking forward to the day when the creators of the unnerving Fox TV show 24 do unto his Jack Bauer character what they've done to so many others: kill him off, brutally, but with few tears. "Don't get me wrong," he says. "I love what I do." But he's thirty-nine years old, a little pent-up and a lot tired. All he's had for the past five years, ten months out of each year, are endless fourteen-hour days of working on the show, gun in hand, eyes squinted, voice on ultra-incredibly intense, saving the world with methods that might not be right but are never wrong. He has no girlfriend in his life, no affection or release of that sort. Sometimes he feels trapped, caged, really. And then, as a consequence, he occasionally falls into the scotch bottle and ends up making a messy spectacle of himself.

"There's a point that I get to where I just go, 'F--k it,' " he says one day in Los Angeles, where he lives in the somewhat seedy Silver Lake district, in the vast, open expanse of a former iron foundry. "It's selfish and self-absorbed and it's a dangerous thing, thinking that if you work really hard, you should be able to reward yourself by going out and getting s--t-faced. I should be able to wake up in the morning without going, 'Oh, no! Where's my boot?' Or 'Where am I?' Or 'One of your friends didn't happen to bring my car home, did they?' It's not a very clever way to live, and I don't want to live like that. But it's the kind of trade you have to make."

I'd once read that, in public, Kiefer renders "a kind of bluff, surface friendliness that seems to conceal something else." This has also been the gloss on his father, that towering figure of an actor, the great Donald Sutherland, who once helped define eras, with movies like M*A*S*H and Klute. Certainly the two look alike, with their weird, low-slung earlobes, their chipmunk cheeks and their mischievous devil's-work grins. But as far as the son goes, I find him surprisingly forthright, gamely willing to talk about anything you want to talk about -- his two failed marriages, his luckless 1991 engagement to Julia Roberts, his disapproval of foods with certain textures, and assorted other upsets, including drunken run-ins with Christmas trees, his (former) tendency to get into bar fights and that time in his life, just before 24, when he was churning out very bad flicks just for the money.

Right now, though, he's guiding me through his beloved collection of vintage guitars (a '59 Les Paul, a '67 Telecaster, a '68 ES335 and about fifty-five more) and saying guitar-nerd things like "See, this one's got a Jimmy Page switcher, so I could have a double-coil pick-up here and a single coil here and reroute it all the way through. Just amazing tonal quality!"

And then, a few moments later, after easing silkily through some Hendrix on one of his acoustics, he says, "Want to go out? I'll take you on the subway. That's how I get around. We can have a drink that way, because I can't do the driving and the other."

"You can't?" I say.

"Noooo," he says. "That would be bad."

As a kid he was tossed about some. One minute he's being born in England, his extravagant dad setting him up in life with the extravagant name of Kiefer William Frederick Dempsey George Rufus Sutherland, the next he's living in Los Angeles. He's three. His mom, Canadian actress Shirley Douglas, and his dad aren't getting along. In fact, his dad is carrying on with Jane Fonda. The marriage dissolves. His mom goes away, leaving Kiefer and his twin sister, Rachel, behind.

It's during this time that Kiefer evolves his first real memory of his father. His father, the larger-than-life movie star, wears his hair long, wild and tangled, with a great big beard to match. A leather coat occludes his shoulders. He drives his son to preschool in a Ferrari he won in a poker game. His father is "different." The other parents stare. Kiefer likes how they stare and by his mid-twenties he will dress similarly, drawing similar stares, albeit from within a 1970 beater Porsche 911, not a Ferrari.

After six months, his mother returns and eventually takes him back to Canada. Over the next ten years he attends seven different schools, learning to make friends by making the other kids laugh. He's insecure, nervous, a compensating cutup but not a great student. In his fifteenth year, he drops out of school, determined to be an actor, despite the usual parental misgivings. Shortly thereafter, he lands the lead in a coming-of-age film, The Bay Boy, and is nominated for a Genie award, Canada's Oscar. With a $30,000 payday in his pocket, he descends on New York and the actor's life. A year later, nearly broke, he moves to L.A. and for a few months lives out of his sweet '67 Mustang. In 1985, he gets his first Hollywood movie, from Sean Penn: a small role in At Close Range (with the greatest tag line ever: "Like Father. Like Son. Like Hell."), most of which ends up on the cutting-room floor. Around the same time, he lands a part in the Steven Spielberg TV show Amazing Stories, and, as he likes to say, "When Steven Spielberg hires you, that's good for three jobs easy." And so it was, first as a gang leader in Stand by Me, then as the most raffishly charming vampire ever in The Lost Boys and as a sensitive cowboy in Young Guns.

He's thinking , "Well, this is easy. I am that good. And it's just going to keep going."

He was twenty-one years old. What else would he think?

But what interests me most about this period in Kiefer's life are those six months early on that he spent separated from his mom. He says it's no big deal -- "It wasn't unusual for any member of my family to go away for quite some time" -- but you have to wonder.

I ask him if he knows where she went.

"I've never been really quite sure," he says. "I think she may have gone back to Canada for a while."

So, he's never asked her about it. "And have you ever talked to your father about his affair with Jane Fonda?"

"No."

"What do you imagine that conversation would have been like?"

"He'd probably say, 'I fell in love.' I understand that. People do. And when they're falling in love, they believe in everything so strongly and passionately, this kind of heightened experience, that it's very hard to judge somebody for it."

That, of course, is what the adult says looking back at the child. How the child might have felt, and how those feelings might have worked on the child in later life, Kiefer doesn't come out and say.

Page 2:

These days, the neighborhood he chooses to live in is predominantly Salvadoran, and at night there, walking his dog, a border collie named Molly, he's been held up with a gun pressed to his noggin. His place is huge, almost a quarter-acre in size, not cut up into rooms but left wide open, with only a half-wall to partition off the sleeping area. Showing me around, he says, "It took a while to get used to sleeping in a barn." Kiefer has at times led a kind of messy life, but his home suggests an almost obsessive attachment to order. Nothing is out of place. His bed is made and looks freshly plumped; the pack of Camel filters on the bedside table has been set down square to the corners. No dirty dishes or food crumbs mottle his kitchen sink. His guitar collection is neatly arranged according to make and body style.

Eventually, this attention to neatness comes up during a discussion about his various possible failings as a boyfriend.

"I think I'm pretty demanding as a person," he says. "I like things to be a certain way, everything from being on time to being tidy. I haven't been flexible with that. I mean, as I've gotten older, I've hopefully become a lot more flexible. But, of course, I am living alone."

"Does disorder bother you?" I ask.

"I had the 24 cast over for dinner one night and I heard that Reiko Aylesworth, who played Michelle, said, 'It's so nice that he cleaned up his place.' Someone else said, 'He didn't clean it up for you, honey. It's always this clean.' And her response was, 'Ewwww.' But there's so much disorder in every other aspect of what we do, if you can control your environment at home, you do it."

"It's a little freaky to walk into," I say.

"Yeah?" he says, and he says it with a smile.

Why 24 succeeds on the level that it does -- since 2001, it's won or been nominated for dozens of awards, topped critics' lists and been dominant in its time slot -- Kiefer isn't exactly sure, though he does have one main theory: "People respond to a guy who is trapped and succeeds on some level and fails on another."

�It's glib to say so, but that's probably also true of Kiefer himself. For instance, one problem with being tied to a show like 24 is that, while you might succeed on some level with girls -- with the occasional one-night stand and so forth -- you can forget about anything deeper. Kiefer often, and at length, bemoans this fact.

"I've had one-night stands, but they're just not my nature," he says. "I think of myself as much more of a romantic than that. The point of being with someone is out of the hope and desire for connection. Otherwise, you might as well just go home and masturbate. Actually, there is someone who I really like a lot. But it feels like all I do is work and sleep. If you're just into that, you're fine. But if you're hoping to fall in love, you're dead meat. It f-----g ain't going to happen. You're going to fall apart and not make it."

"Ever been to a shrink?" I ask him, apropos of nothing, really.

Page 3.

"Oh, yeah," he says immediately. "The first time I was seven, because my mother was concerned that damage might have been done to me by the disruption in our family."

"And was there?"

"I don't think so. Some other people might disagree. But I don't think there was."

And yet he does seem driven to try to successfully complete what his parents couldn't and, like them, has always ended up failing. He first got married when he was twenty, to actress Camelia Kath -- they had a daughter, Sarah Jude, now eighteen -- but the marriage lasted less than two years, reportedly falling apart when he couldn't manage to stay out of bars and the arms of other women. He flung himself in there again, in 1996, with former model Kelly Winn, but separated from her after four years, for basically the same reasons. And then in between those two unions was his ill-fated engagement to Julia Roberts, whom he met while making Flatliners in 1990. They were the ultimate Hollywood couple, the Brad and Angelina of their day. Three days before their wedding, however, she called it off and flew to Europe with Kiefer's then best friend, Jason Patric, unleashing a s---storm of lurid tabloid-type press -- allegedly, Kiefer had been carrying on with a stripper, which he denies -- and also ensuring that in all stories about him to follow, he'd be called upon to comment about the great big mess.

"I commend Julia for seeing how young and silly we were, even at the last minute, even as painful and as difficult as it was," he says to me one day, obligatorily. "Thank God she saw it."

"Have you forgiven Jason Patric?"

"It's not a matter of that. We were friends, and I'm surprised that I never got a call from him saying I've fallen in love with da-da-da. Instead, I found out from a stranger."

"Did your dad offer any advice?"

"I think he just went, 'Oh, son...' "

Since then he's not seen Roberts, nor did he call to congratulate her on the birth of her twins. Reports have suggested that she's miffed about that. But why should she be? What happened happened fifteen years ago. You move on. Kiefer, for his part, says he doubts he'll ever even get close to walking down the aisle again.

What happened to his movie career after the Julia flap is still a sort of perplexity. He was great as a Bible-thumping Marine in A Few Good Men (1992), as a KKK nut job in A Time to Kill (1996) and as a serial killer in Freeway (1996). But he was also showing up in a lot of hooey, like The Cowboy Way (1994), not to mention a lot of utter crap, done just for the money, the names of which he is loath to reveal (Renegades? Chicago Joe and the Showgirl?). Confused and revolted by his own venality, he retreated to a cattle ranch he bought in California's Santa Ynez Valley. Oddly enough, he took up steer roping and, with his partner, a professional roper by the name of John English, developed his skills to the point where he could travel the rodeo circuit and win a number of competitions (and break all of his fingers). Then, in 2000, he got a call from his friend Stephen Hopkins, a British director working on the pilot for a narratively experimental real-time TV show called 24. Was he interested in the lead? Kiefer didn't see how he could lose. If the pilot sucked, no one would see it. If it didn't, well, maybe he'd have a job to do for a year or two.

"But it was also one of those things," he says. "When 24 became a hit, people started saying things like, 'Comeback this,' and, 'Resurrected-from-the-dead that.' At first I was like, 'Resurrected from the f-----g dead? What the f--k does that mean?' But sometimes the brain doesn't let you realize the kind of trouble you're in."

Now he's got a lot more going on than just the show. There's his new movie, The Sentinel, opposite Michael Douglas, in which he plays a Secret Service agent caught up in a plot to assassinate the president. Plus, he's started a record label, Ironworks Music, with his friend Jude Cole, which just released a record by its first signed band, Rocco DeLuca and the Burden. And then, of course, there's the trouble that follows whenever he attempts to blow off steam and find equilibrium in a bottle of scotch.

Page 4.

The trouble has always been around, in one form or another. Well in the past, there have been arrests for driving under the influence and humorous episodes with others arrested for the same thing, like the one with actor Gary Oldman in 1991. Starting to laugh, Kiefer says, "They were handcuffing him and he was on his knees, right level with the window of the car where I was. He had his head down and he looked up and he said, 'Right. Maybe next time we just have lunch.' That was the coolest kind of Cool Hand Luke line. I just loved hanging out with him. But that was a long time ago."

He's also been in a number of bar fights, including the one where some guy insulted his wife ("he licked her foot") and he got a little carried away. "I just kept hitting, hitting, hitting, hitting, hitting. 'Don't f-----g stop, because you don't want this guy to get up.' I felt awful after that. I remember thinking that life is too short to behave like this."

But for the most part, Kiefer is known as a do-anything-for-a-laugh kind of fun inebriate. One time he launched himself into the pool at the Beverly Hills Hotel, fully clothed, to get some yuks. Another time, according to tabloid reports, he downed eight shots of J&B Scotch at a bar, stripped off his shirt and gyrated topless before lap-dancing on a guy's knee. But perhaps the most emblematic episode occurred last Christmas, inside London's Strand Palace Hotel.

"After a marathon booze bender with pals," wrote The Sunday Mirror, "a huge Christmas tree caught [Kiefer's] eye. 'I hate that f-----g Christmas tree,' he declared. 'The tree has to come down.' Kiefer warned staff: 'I'm smashing it -- can I pay for it?' A staff member replied, 'I'm absolutely sure you can, sir.' [He] then hurled himself into the Norwegian spruce, sending baubles and lights crashing to the ground.... Pulling pine needles out of his hair and T-shirt, he said to a hotel employee, 'Oh, sorry about that...you're so cool. This f-----g hotel rocks!' "

Kiefer says this account is fairly accurate and disputes only his quotes. "I didn't say anything," he says, "and that's what was funny. It was a joke, done to make someone laugh. And the tree was fine. It was fine."

"Is drinking your most self-destructive behavior?" I ask him, knowing the answer.

"It's absolutely caused me the most grief."

"Because of what you do when you get drunk or because you have a drinking problem?"

He considers this for only a second. "I'd have to say a bit of both. And because I'm a public person, I've embarrassed my mother and my family and, most specifically, my daughter. It's been the biggest problem for me. I have a few drinks and I'm not so worried about tomorrow and not thinking about yesterday. I am in this moment and I don't give a s--t about anything else, and that's that. It's right out of the textbook on problem drinkers. And I'm not stupid. I know it's my fault, usually in an effort to make someone laugh. And then the next day, I go, 'Oh, God, don't let me do that again.' So why do I do it again? And again? And again?"

He lets the question hang there. He seems truly exasperated. I suggest that maybe it's the adult equivalent of what he did as a kid who had to make a new set of friends every year and did it by making them laugh.

"Yeah," he says levelly. "But you might want to move past that at a point, don't you think? You want to move forward."

And that's another thing that's great about Kiefer: He doesn't try to hide or adjust for public consumption his various little complexities, peculiarities, embarrassments and contradictions. He says things like, "The last movie I cried at? Oh, f--k. Oh, I'll be honest with you. Oh, f--k, I don't know if I can. Oh, well. I think it was Love, Actually. Yeah. I'm no different than anybody else." He has those "texture issues" with food and says, "Avocado used to freak me out, I've never liked cheese, and runny eggs make me want to ralph." He says that sometimes he calls his father "Dad," but mostly he calls him, "Hey," as in, "Hey, what're you doing?"

He likes to tell this story about his father: "At one point before the divorce, we didn't have any money, and his one pair of pants had a hole in them, but my mother's a tough lady, and he was nervous about asking her to sew them up. So where the rip was, he just painted his ass black to match the pants. That's his sense of humor." Then he'll tell you that, like his dad before him, he often chooses not to wear underwear himself.

He has never, ever tried to quit smoking.

The first tattoo he ever got, he narrowed his choices down to the Chinese character for strength and Mickey Mouse in a space helmet, before settling on the former. He once heard that some college-going 24 fans had developed a drinking game in which you have to down one shot for every time Jack Bauer says, "Damn it," which is the show's "f--k" and "s--t" substitute. So during one episode, in one scene, he took it upon himself to say "Damn it" three times in a row, "Boom, boom, boom. And that was just one scene. By the end, there had to be fourteen 'Damn its.' And I could just see all these college kids going, 'Oh, f--k!' "

He only has two mirrors in his home. "I've always thought that I look different in my head than what I see. I had a real big problem with it when I saw Stand by Me. I thought I'd ruined the movie. I so clearly wanted my character to be a mean, angry version of James Dean. And, obviously, I didn't look anything like that. That's always thrown me off. So I tend not to look in mirrors."

He calls his home the cave and says things like, "Ultimately, I don't want to live in the cave forever."

The night that Kiefer and I hit a few bars -- he favors anti-glamorous ones, narrow and sedate, with mostly locals inside -- he is greeted in each with the same line. "Where you been?" the bartenders want to know. He says something about his tough 24 schedule and orders a J&B neat, with a Coke chaser. For the past five years, he's largely been surrounded by the same people, mostly the 24 cast and crew. They know him so well when he speaks to them it's in the shorthand of old friends, with him rarely having to think any deeper than the first thought that pops into his mind. But with me around, he says he's had to explore himself a little more, and he likes it.

He talks fondly about that first year in L.A., living in a house rented by Sarah Jessica Parker, with fellow struggling actors Billy Zane and Robert Downey Jr. "I've been thinking about how young we were," he says. "Some of us were going to a strip club one night. When we all met downstairs, every one of us was wearing a trench coat, in the middle of the summer, in Los Angeles. This was our idea of what you did when you went to a strip club. We started laughing, but not one person took that f-----g jacket off."

He shakes his head, happily.

"I remember the first girl I slept with," he goes on. "She was seventeen, I was thirteen. I remember leaving her house after we'd done it, like, seven times, and I remember skipping to the bus stop, going, 'I've done it seven times.' And I was literally skipping."

He shakes his head again.

Outside the last bar of the evening, the bouncer says to him, "It's a good thing you haven't left yet. These girls gave me orders if you leave before they make out with you, I have to beat you up."

Kiefer raises his hands. "Don't do it!" he says comically.

The girls, a couple of plain Janes named Jennifer and Nicky, stumble out and get Kiefer to pose for pictures with them.

"Thank you," he says afterward. "God bless your hearts."

Everyone looks pleased. One of Kiefer's favorite bits of dialogue comes from the movie Flatliners. On the way to the subway, he says it. He says, "In the end we all know what we've done." And then, maybe for good measure, he says it once more.

(From RS 998, April 20, 2006)

Drinking to forget with TV's hottest action hero

By Erik Hedegaard - Rolling Stone

Page 1.