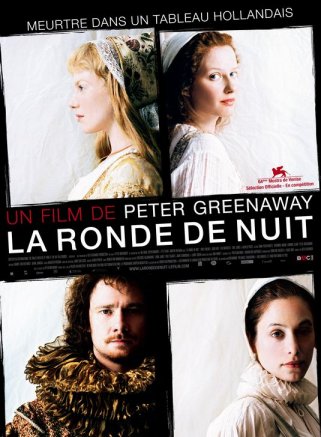

David Stratton speaks with Writer/Director, Peter Greenaway and actors, Martin Freeman and Eva Birthistle about Nightwatching, based on Rembrandt’s painting The Night Watch.

Nightwatching

“Context, context, context!” As declared by a certain famous Dutch Master in Nightwatching, that line cuts to the heart of any discussion of Peter Greenaway. A British director whose rep rests on such elegant and profane arthouse staples as The Draughtsman’s Contract (1982) and The Cook, the Thief, His Wife and Her Lover (1989), Greenaway loves nothing more than juxtaposing images culled from the history of visual art with arcane ideas derived from the annals of science, philosophy and literature.

An unrepentantly brainy filmmaker who infamously proclaimed that “cinema is far too rich and capable a medium to be merely left to the storytellers,” Greenaway frequently ran the risk of disappearing up his own arse. And that, unfortunately, is mostly where he’s been for the last decade as far as his movie career is concerned.

Now — or rather back in late 2007, when Nightwatching first played TIFF — two men helped lead him out. The first is Nightwatching’s subject, Rembrandt van Rijn, presented here as he paints The Night Watch, the 1642 masterpiece that officially depicts the Amsterdam VIPs who commissioned it but — as Greenaway purports both in this feature and his subsequent documentary Rembrandt’s J’Accuse — may hide details of a secret murder plot. The other man is Martin Freeman, the actor and former Office star whose lusty performance as the artist gives Greenaway’s bold, complex if sometimes infuriating new movie a vibrantly human core.

As for the matter of context, Nightwatching contains an awful lot, exploring the social, political, economic and even sexual minutiae of Rembrandt’s life. “You do end up with the accusation that you tried to pack too much in and the film becomes an art-history lesson,” admits Greenaway, who was interviewed alongside Freeman. “That’s a problem to solve. But I hope we were able to steer our way through the worst excesses.”

The film renders Rembrandt as a brilliant but stubborn man who becomes the painter of choice among Amsterdam’s elite but ultimately can’t stomach the venality and hypocrisy of his clients. The Night Watch is his opportunity to vent his spleen, much to their displeasure.

“I like the fact that he couldn’t bring himself to do a boring painting,” says Freeman. “He couldn’t knuckle down and do it. Of course, how much of this is Peter’s conceit and how much of it is fact? I’m still not really sure of it. But I like the version that we are telling anyway.”

Unusual for films about artists, Nightwatching does not portray its subject of some wan, solitary soul but a man of his time who’s very willing to swim with the sharks. Freeman notes that Greenaway wanted Rembrandt “something that was 3-D and not projected onto a pedestal.”

“This was done in a Dutch context, too,” says the director, who’s lived in Amsterdam since the ’90s. “[They] have proverbs like ‘To be ordinary is extraordinary enough.’ They keep their feet really on the ground. I would like to think we made Rembrandt look like a good craftsman. He’s certainly a businessman, too.”

Emphasizing that hard-nosed sensibility, Freeman delivers his best performance to date. (It’s his nakedest, too.) The director was pleased that the actor and the painter were so well-matched. For one thing, the two had a plausible physical resemblance. The director was also impressed that Freeman could handle the sometimes unwieldy material placed in front of him.

“Like everybody else in the world, I’d seen him on The Office,” says Greenaway, “He’s got this almost intuitive way of handling dialogue and that magnificent timing. He’s got this amazing ability to take a piece of dialogue which could look quite stiff on the page but make it really work in context.”

As for what the opportunity meant to him, Freeman is frank. “These things don’t come my way very often,” he says, “but to be honest, they don’t come anybody’s way. I have to say not many people make films like [Greenaway] does. And he doesn’t make a film a year, so this is all quite rare. I thought he and I would be an interesting combination, and I thought he and Rembrandt were an interesting combination.

“What I also really liked was that I knew it was going to be f***ng hard,” he adds. “I knew it would be really hard from an acting part of view and a logistical point of view. I wondered if I could do this without killing somebody and having a nervous breakdown.”

In the end, no such unpleasantness was necessary. And though Rembrandt’s painting doesn’t quite produce a cinematic masterpiece in Nightwatching, the film’s intellectual ambition, formal audacity and own bloody-mindedness do the dead Dutchman proud.

'Nightwatching' sexually-charged art

4 out 5 stars

(This film is rated 18-A)

Nightwatching, Peter Greenaway's clever conspiratorial take on the creation of Rembrandt's The Night Watch, is everything fans of the director want to see.

It's bawdy, smart, mannered and shot with a texture that's inspired by and true to the subject matter. That is to say, it is framed and lit like a painting -- a metier with which the sometime artist Greenaway is intimately familiar.

It is both imaginative historical fiction (despite all its idiosyncrasies, there is no real evidence Rembrandt was trying to communicate any message of nefariousness in his world-famous commissioned portrait of the Amsterdam Civil Guard), and refreshingly human. One of the greatest painters in history is, here, portrayed by a comic actor (Martin Freeman, of Britain's The Office and A Hitchhiker's Guide To The Galaxy) with little gravitas but plenty of sympathy, humour and ultimately nobility.

Indeed, the Rembrandt van Rijn we are introduced to, naked (as are many of the women in the movie at various times), is one whose life, work and appetites tend to dovetail. His sex life overlaps between his mistresses, his models (Rembrandt painted nudes with a realism unique for the time) and his agent-turned-wife Saskia (Eva Birthistle). In fact, one of the movie's real strengths is its female cast, particularly Nathalie Press as a pubescent scullery maid who inspires Rembrandt as she tremulously faces the daunting life ahead of her as a woman in that world.

This Rembrandt is a sharp-tongued social gadfly who gets away with painting against the grain of public sensibility and getting paid handsomely for it.

But fortunes change, and with the added responsibility of Saskia's pregnancy (a difficult one that adds to the drama), Rembrandt is forced to "sell out" and accept a stodgy commission that he considers beneath his talents - the Amsterdam Civil Guards portrait.

His hard-feelings toward military portraiture and the static rendition he's expected to deliver leave him predisposed to think the worst of his subjects. And luckily for the plot, they do turn out to be a bunch of power-hungry oafs and knaves, capable even of killing their own.

Mere disgust turns to dark loathing when one of the few Guards he's friendly with, Piers Hasselburg (Andrzej Seweryn) is killed in a shooting "accident." His suspicion of murder leads him to a cesspool of sexually-charged jealousy and the revelation -- via a troubled servant-girl named Marieke (Natalie Press) -- of their involvement in a brothel of painfully young indentured servants.

And with that, our historical figure turns from self-serving free spirit to rebel with a cause, letting his muse turn a standard portrait into a series of clues to all the dark goings-on -- effectively committing career suicide. In effect, the murder is Nightwatching's MacGuffin, a mere catalyst to the artist's character arc, which is richly portrayed by Freeman.

Nightwatching is, in the end, a sexually-charged work of febrile imagination and labyrinthean 17th century politics. And it succeeds in the daunting task of turning a historical icon into flesh and blood, with all the fear, lust and emotion that entails.

Nightwatching: Has it really only been 367 years in the museum?

Film Review: Nightwatching (2 stars)

A word to the wise: It helps to know something of the painter Rembrandt van Rijn, and of one of his most famous works, The Night Watch, prior to tackling Peter Greenaway's epic, convoluted story of its creation. Prior to and since seeing this film I've spent time on Wikipedia and various Dutch art sites, and even considered a trip to Amsterdam's Rijksmuseum to take in the original, perhaps with a little coffee shop confection on the side to mellow the experience.

The back story is simple. In 1642, Rembrandt completed a large (more than three by four metres) painting of a company of militiamen heading out on manoeuvres. It was unique at the time for showing its subjects apparently in motion, as in a candid photograph, rather than arranged around a table or standing in ranks. A myth has grown that the public reception was harsh, but there is no record of this, and the painting was proudly displayed in the ballroom of the militia headquarters for more than 70 years before being moved to Amsterdam's town hall.

Greenaway, a fan of Rembrandt and a painter before he was a director, has created a film that posits internecine plotting among the members of the company, with Rembrandt (Martin Freeman of Britain's The Office and The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy) as a kind of painterly detective, gathering clues about the death of one of the soldiers and immortalizing his suspicions in the painting for all to see. (Well, all with an arcane knowledge of 17th-century Dutch allusion and allegory.) Coincidentally, Greenaway followed up this 2007 film with Rembrandt's j'accuse, in which he disparages modern visual illiteracy. Il nous accuse.

Nightwatching is a visual feast. Greenaway has taken the style of the Netherlands golden age of painting and made it the palette and framework for his film. It's as if Amsterdam of the 1600s actually looked the way its artists captured it in oil. (Thank heavens Greenaway isn't into cubism.) Figures are illuminated by strong directional light and surfaces are artfully arranged with still life subject matter. Diners even eat lined up on just one side of the table. The overall effect is one of well thought-out artifice, like a detailed theatrical stage set.

Greenaway, never one to be accused of romanticism, takes pains to show the messy personal and commercial aspects of the lives of the Old Masters. In one scene, Rembrandt visits a gallery and calculates the artists' commissions based on the number of people in each painting; full-length figures cost more than half-lengths, which were more expensive than heads-and-shoulders, and so on. It's easy to forget, standing stoned in a Dutch art museum, that most painters weren't putting brush to canvas for immortality or future enlightenment but to pay for next winter's coal. (Or, in Rembrandt's case, to deliver a secret message; this is a kind of Da Vinci Code on a secular scale.)

Freeman delivers a good performance; if he is uncertain whether to adopt a naturalistic, or more stilted, theatrical delivery, he at least sticks to one or the other in a given scene. (The wavering, I'd wager, comes from the directorial level.) He is surrounded by a retinue of able if not well-known names, the strongest of them the womenfolk: Eva Birthistle plays Rembrandt's wife; Nathalie Press (50 Dead Men Walking) a waifish orphan girl; and Jodhi May a servant who becomes his mistress.

Nightwatching runs a shade over two and a quarter hours and outstays its welcome for all but the most fervent Rembrandt enthusiasts. When The Night Watch was first relocated in 1715, it was cut down on all four sides to fit its new home, a common practice at the time. Two characters and some of the background was lost. Call me a visual illiterate, but Nightwatching, which screened at the Toronto International Film Festival in 2007 and is only now getting a limited release, might have benefited from a similar trim.

Nightwatching: Maddening art mystery

2 out of 4 stars - Starring Martin Freeman, Eva Birthistle, Jodhi May and Emily Holmes. Written and directed by Peter Greenaway. 134 minutes. At the Cumberland. 18A

The phrase "exasperating elegance" comes to mind in assessing Nightwatching, Peter Greenaway's latest flight of fancy.

The Welsh auteur is in his element in bringing Rembrandt's famed "The Night Watch" to dramatic life, taking a leaf from author Dan Brown's profitable fascination with the artwork of Leonard Da Vinci. More art director than film director, Greenaway puts his visuals ahead of his narratives at all times.

He isn't one to sully his defiantly outre stance by making anything as mainstream as The Da Vinci Code, however. Although Nightwatching is his most linear narrative in some time – and a good deal more satisfying that his tiresome Tulse Luper multimedia indulgences of recent years – Greenaway continues to vex anyone who seeks anything so prosaic as a good story.

What truly galls is that Greenaway has the germ of a great movie here. "The Night Watch" is one of the art world's finest mysteries, with unorthodox elements that have fascinated viewers since the 17th century. Who are the military men depicted in it? Why do they strike such a relaxed pose? Who is the girl at the centre left of the painting, and what does she represent?

Greenaway ventures opinions on all of these questions, but does so obliquely and with no assist to the befuddled. He employs whimsy and pathos to follow the painting from its original commission for Rembrandt (Martin Freeman), which the artist regards as strictly a paycheque gig, through to its completion and subsequent mixed reception.

"Goddamned painting of the militia pretending to be mighty soldiers!" Rembrandt grouses to his wife Saskia (Eva Birthistle), after he is bullied into the assignment by supporters and members of the Amsterdam Musketeer Militia.

Along the way, Rembrandt encounters complications both philosophical and sexual. The former comes by way of his growing dislike of his subjects and his suspicions that they are allied with murder and child prostitution.

On the latter complication, he proves himself easily distracted by the charms of Geertje (Jodhi May), who is far more attentive to him than the pregnant and moody Saskia. Freeman and May are explicitly and repeatedly viewed in the buff, but Freeman has had ample experience in this, since he played the unlikely porn star in Love, Actually.

He's also an unlikely Rembrandt, but a good one, bringing to mind Tom Hulce's energetic portrayal of the composer Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart in Amadeus.

How maddening it is, though, that Greenaway refuses to stitch together anything resembling a coherent storyline. Most of the characters are ill-defined, their scenes disjointed (when not downright mystifying) and their dialogue is often drowned out by a classical score that strays into the bombastic.

Visually, however, Nightwatching is above reproach. Greenaway poses his subjects and lights them much the way Rembrandt did, and the interplay of shadows is amazing. You want to slap the ninny who complains, gazing upon the completed painting, "Bring on some candles!"

But then you might also feel like slapping Greenaway for being such a stubborn and uncompromising cuss.

Cracking the Rembrandt code

Written and directed by Peter Greenaway

If it came from a more commercial filmmaker, Nightwatching could be marketed as a cross between Shakespeare in Love and The Da Vinci Code, combining a lusty, down-to-earth portrait of a great artist and a secret meaning behind a famous painting. But Peter Greenaway, the English director of such lush and strange films as The Cook, the Thief, His Wife and Her Lover, and The Pillow Book, is nobody's idea of a commercial director. His fans will appreciate this eccentric exercise in hypothetical art history.

Nightwatching is about the history of Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn's painting The Night Watch, completed in 1642. Replete with beautifully lit theatrical tableaux, the production design (especially the famous chiaroscuro of Rembrandt's paintings) and Wlodzimierz Pawlik's baroque-sounding score feel like the real stars of the film, as they bring the painter's world to the screen. In a somewhat secondary role is English comic actor Martin Freeman (The Office), who plays a sort of rumpled Cockney version of Rembrandt.

Depicted as a savvy but abrasive rural miller's son, Freeman's Rembrandt often speaks directly to the camera, pronouncing on everything from the 17th-century political climate to the era's pricing system for commissioned portraits. The depictions of his domestic and professional difficulties serve as bridges between the film's tableaux.

Like a modern filmmaker, Rembrandt is shown as a painter who casts and dramatizes his paintings, striding about his studio, placating and inspiring his subjects, while dealing with various financial stresses. You almost expect him to call out: "Lights, action - paint!"

The story focuses, though, on a painting that was commissioned by the Amsterdam Civil Guard and is now the showpiece of Amsterdam's Rijksmuseum. Famous for its size, dramatic use of light and shadow, and introduction of dynamic movement into the traditional static group portrait, The Night Watch also has a number of puzzling elements, including the presence among the soldiers of an adolescent girl, who is carrying various symbols of the militia group.

The title is considered inaccurate; a layer of dark varnish, removed in the 1940s, had left the mistaken impression that it was a night picture. But for Greenaway's purpose, the darkness - the famous Rembrandt black - is a central metaphor. As he sees it, Rembrandt gazed into the abysmal darkness that surrounded Amsterdam's golden age. In repeated scenes, the painter goes to the roof of his house to stare at the night sky. One night, he meets an adolescent girl, Marieke (Nathalie Press), an orphan who wanders the city's rooftops like a mysterious angel.

After his wife becomes pregnant, Rembrandt reluctantly takes the Guard's commission to paint their group portrait. They are depicted as fat-cat merchants and aristocrats who like to play soldier. As he begins to work on the nine-month-long project, though, Rembrandt also begins to uncover a series of scandals about his subjects: There appears to be a murder cover-up; as well, he learns that the orphanage, under the Guard's care, is actually a child brothel.

Eventually, he uses the painting to condemn his powerful subjects' vices. When the work is completed, the subjects are furious. But they accept the painting - lest by rejecting it they confirm his accusations - and plot their revenge.

Nightwatching also depicts Rembrandt's domestic life, including the three women with whom he had relations. These include his wife, Saskia Uylenburgh Eva Birthistle), who died of consumption; his son's caregiver, the lusty Geertje (Jodhi May); and finally a much younger maid, Hendrickje Stoeffels (Emily Holmes). The three actresses lend some welcome human warmth to the puzzle-box of the plot.

Greenaway appears to take his conspiracy theory about the painting seriously - he outlined it in a documentary last year called Rembrandt's j’accuse - but viewers aren't required to buy in to enjoy the film. And if Greenaway's thesis seems as cockamamie as any of Dan Brown's fictional conjectures about the Last Supper, his aim is higher.

The idea that a particular image is the product of a collision of forces, from the artist's libido to the political atmosphere of the time, adds to, rather than reduces, the work's meaning.

BY Jason Anderson

EYE WEEKLY

March 04, 2009

Martin Freeman as Rembrandt

CANOE -- JAM! Movies - Nightwatching Review

By Jim Slotek – Sun Media

March 7, 2009

Alliance Photo: Martin Freeman of Britain’s The Office and The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy stars as Rembrandt.

By Chris Knight

National Post.com

March 5, 2009

By Peter Howell – Movie Critic

TheStar.com - Entertainment

March 6, 2009

Rembrant, Geertje, Saskia, Hendrickje

By Liam Lacey

globeandmail.com

March 6, 2009

Starring Martin Freeman

Classification: 18A

3 stars