This web page is dedicated to 24's Kiefer Sutherland. You will find articles and web sites relating to him on this page. Hopefully, you will find something that will interest you.

Bernard B. Jacobs on Broadway: The Shubert Organization

That Championship Season:

Two-time Olivier Award winner Brian Cox (The Bourne Identity), Jim Gaffigan (Salvation Boulevard), Golden Globe nominee Chris Noth (The Good Wife), Jason Patric (Cat On A Hot Tin Roof) and Golden Globe and Emmy Award winner Kiefer Sutherland (24) star in Broadway’s classic drama That Championship Season.

Jason Miller’s Tony- and Pulitzer Prize-winning play returns to Broadway for a strictly limited engagement. Directed by two-time Tony Award winner Gregory Mosher (A View From The Bridge), That Championship Season is a powerhouse drama about the promise of youth… and the challenge of staying in the game.

For over two decades, four players and the coach of a high school championship basketball team have gathered every year to re-live their greatest moment of glory. While three of the players have found small-town success, the fourth has never found his way. At this year's reunion, tensions boil over, and as the celebratory evening turns brutal, long-held secrets bubble to the surface and life-long bonds are shattered.

Home -court appeal REVIEW

By Kristie Grier Ceruti - Editor

The Abington Journal, Clarks Summit, PA

March 16, 2011

NEW YORK CITY, N.Y. - From the detailed set to dialogue reminiscent of an earlier era, “That Championship Season” director Gregory Mosher holds true to playwright Jason Miller’s presentation of his hometown “Lackawanna Valley” in the early 1970s.

Born in Long Island City, Queens, Miller was raised in Scranton and graduated from St. Patrick’s and the Jesuit-run University of Scranton. The playwright and actor won a Pulitzer Prize in 1973 for “That Championship Season.” Miller also won a Tony Award for the play and was nominated for an Oscar in the same year for his portrayal of Father Damien Karras in horror movie “The Exorcist.” He died of a heart attack May 15, 2001 in Scranton at age 62.

In the play, which opened March 6 at the Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre in New York City, four members of a 1952 Pennsylvania state high school basketball championship team gather annually with their beloved “Coach” at his family homestead. A“625” address etched in the window above the front door, hardwood balustrades polished to a high gloss and stained glass accenting the stairwell could be found in any of the many former coal-baron estates in Northeastern Pa.

The black rotary telephone situated on a side table, cast iron radiator in the corner of the parlor and gun cabinet in the entryway capture the period.

“Coach’s” mantle represents his framework: photos of his mother, JFK, and of course, the nearly 18-inch tall silver basketball trophy. They take second stage only to a wall portrait of his icon Teddy Roosevelt.

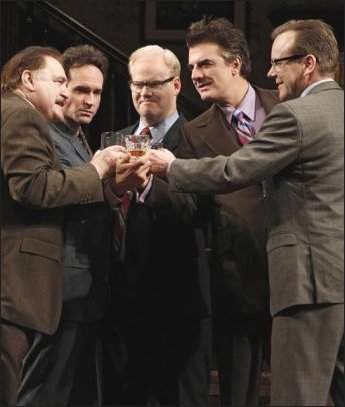

A long-awaited evening of revelry deteriorates from clinking rocks glasses of Jameson Irish whiskey and recollections of basketball plays to physical conflict, angry outbursts and betrayals.

And that’s in Act One.

The evening is well spent with Kiefer Sutherland’s “James Daley,” a school principal self-described as “exhausted at 38.” His 1950s browline glasses are the perfect fit for a neat, nervous, elder brother. The closest he comes to diffusing the bombs faced by his primetime TV persona “Jack Bauer” on ABC’s “24” is in acting as mediator for his former teammates during most of the gathering.

He hitches his wagon and aspirations for a school superintendent slot as a campaign manager for current mayor “George Sikowski,” played by Broadway newcomer Jim Gaffigan. And from his pale bald spot, short-sleeved dress shirt and weak constitution, the stand-up specialist is convincing as a has-been schmoozer, right down to his shiny cordovan lace ups.

And although he is a politician, the mayor is far from politically correct as he spews racial and ethnic epithets about his running mate and even his own best friends.

Enter “dirty, dumb Dago,” “Phil Romano” whose striplands keep the mayor in campaign dollars and himself in “$300 silk handmade suits.” Chris Noth trades his “Sex and the City” limo and driver for a Cadillac and a pinkie ring. And if not an exceptional visual match for a Mediterranean- made man, he slides perfectly into character and his defining downfalls of easy infidelities against his environment and wife.

“Romano” makes a memorable late- night meal of overdone chicken while never soiling his cuff-linked shirt. He blames his delayed arrival on a run “to Old Forge” for cans of Schlitz beer. But it is not difficult to picture the lothario whisking his 17-year-old Scranton girlfriend to Philadelphia for an abortion, as is rumored by the mayor.

Jason Patric’s “Tom Daley” is the one character who earns consistent, genuine laughter with his well-timed sarcasm. He delivers the role of resident “rummy” without ever overplaying the physical comedy.

He describes his reaction upon receiving an old-fashioned Mass card from one of his friends during a recent hospital stay: “(I) thought I was dead when I saw it.”

Although “Tom” seems to win battles of words and wits frequently, the younger Daley makes several efforts to escape the company of friends, brother and coach. Once he wanders off to the “can,” another time to the front porch. But for one instant he stands in the entryway of “Coach’s” home staring into a glass hutch of books and decorations, among them an urn. Reportedly, it actually holds the ashes of the 44-year-old actor’s inspiration for this Broadway rebirth: his father, Jason Miller.

His onstage father figure, “Coach” played by Brian Cox, offers the most memorable monologue of the second act, and possibly the entire play. He trades the vest of his three-piece suit for a letter sweater and tries to rally his boys: “We gave this defeated town something to be proud of.”

Despite earlier excerpts of bigotry and boastfulness, “Coach” veers into judgment when he insinuates one of their circle was dealt a “mongoloid” infant as punishment to a wife who “whored around.”

Indiscretions aside, he manages to unify his boys again and again. Early in the night they huddle up, bless themselves and offer a prayer for “Martin,” the fifth in their team who has yet to attend a reunion. Later “Coach” resorts to the big guns by playing the crackling commentary from the 33- speed recording of their 1952 game broadcast. Throughout the reunion they liberally make reference to their hometown’s recent embarrassment: an elephant mascot which was once the mayor’s brainstorm and within moments, a lampoon.

Yet they never address the elephant in the room: that their friendship and mid-life failings are due in large part to 20 years of lies and self-deception.

Fortunately, the director and cast do not deal in similar delusions. They offer an honest effort and homage to their “Lackawanna Valley” legacy.

Stage review: Starry cast is smooth in 'Championship Season'

By Jocelyn Noveck

The Associated Press

March 15, 2011

NEW YORK - A few moments into the new Broadway revival of "That Championship Season," the characters of James, a school principal in early 1970s Scranton, and Phil, a local businessman, bound onstage together, laughing.

There's an immediate, audible ripple of excitement through the audience, and it's not hard to see why: That joint entrance is a TV fan's dream, bringing us both Jack Bauer and Mr. Big, aka Kiefer Sutherland (in his Broadway debut) and Chris Noth.

You can forgive the audience a moment of stargazing. Because soon enough, this flashy cast - which also includes Jason Patric, comedian Jim Gaffigan and the powerful Brian Cox - quickly forms a smooth ensemble, sinking itself into the sobering world of Jason Miller's 1972 Tony- and Pulitzer-winning play, a searing depiction of one drunken night and the ugliness it gradually unearths.

The championship in the title refers to the winning season of a high school basketball team, whose glorious final game remains a moment etched in the minds of both players and coach. These men can still narrate, move by move, the closing moments of their clutch victory: Ten seconds on the clock down by one point Yes!

It's two decades later, as the players meet for one of their annual reunions at Coach's house. They're in their 30s - "heart attack season, boys!" as Coach chirps cheerfully. Three of them are reunion regulars. A fourth has been missing for a few, but is back. Another star player has long been absent, and we don't know why.

The evening begins with hugs, pats on the back, general merriment. Of course, it will all go sour as the night progresses, as drinks are refilled, the Schlitz cans empty, business suits dishevel, grievances are aired, secrets emerge, frustration and resentment reach a boiling point.

Controlling the evening like a conductor is Coach, bombastic, foul-mouthed and bigoted (in a memorable, appropriately larger-than-life performance by the Scottish-born Cox, a Royal Shakespeare Company veteran), a man who bemoans the death of Sen. Joseph McCarthy, one of his heroes. Ailing badly, the man nonetheless holds his former players in his thrall as if they never grew up and took off those uniforms.

There's George, the town mayor, facing re-election and in need of funds to beat back a challenger who looks like Robert Goulet and may have a relative, the men discover gleefully, who was a Communist. (He's also Jewish, which brings out George's anti-Semitic views.) There's James, his frustrated campaign manager and the junior high principal, who harbors political ambitions of his own.

There's Phil, a wealthy businessman who has trouble keeping his pants zipped and bends the rules of both business and friendship. And there's Tom, James' brother, a drifter and an alcoholic who gets progressively smashed, but not too much to point out Coach's hypocrisy with a bombshell later on.

Effective as the quietly seething Tom, Patric comes to the play with a special connection: His father was playwright Miller, who died in 2001.

Gaffigan, perhaps the least known of this star-studded bunch, is compelling in a showy role as the buffoonish but angry and bigoted mayor. "The only thing a Jew changes more than his politics is his name," he sneers of his opponent.

Noth, best known for TV roles like Mr. Big in "Sex and the City" and Detective Logan in "Law & Order," displays a comfortable and engaging stage presence, coming across as charismatic and oily at the same time as Phil, whose allegiance in the mayoral campaign is crucial.

As James, Sutherland admirably plays against type in an unshowy role as a mousy, unappreciated man - he even has lost his teeth - who aspires to more in life. Far from the imposing Jack Bauer, who intimidated and outwitted countless bad guys on "24," James is small and weak, frustrated and angry. "I am a talented man being swallowed up by anonymity!" he rails. It's rather a shock to see him sink into a couch toward the end, resigned and looking even smaller.

Though the play may disturb some with its stark expressions of racism and anti-Semitism, the action is absorbing and well-paced, directed with an expert hand by Gregory Mosher.

At the curtain call of a recent preview, one of the cast members cracked a joke, and the rest of the actors broke up laughing. They left the stage arm-in-arm, still guffawing.

Such easy camaraderie would seem hard to fake, and it serves the cast well. "That Championship Season" has been revived to excellent effect by a talented, committed ensemble of actors.

Miller’s masterpiece is still a champion

Infinite Improbabily

By Rich Howells

Go Lackawanna, Scranton, PA

March 13, 2011

While hunting down a group of mutant terrorists created by William Stryker, government agent Jack Bauer must team up with New York Detective Mike Logan to fight off a group of young vampires and save Michael Emerson from their clutches as a pale comedian mocks them from the sidelines with Hot Pocket jokes.

So maybe that’s not really the plot of actor and playwright Jason Miller’s Pulitzer Prize-winning masterpiece, “That Championship Season,” which began its revival on Broadway last Sunday. But its all-star cast of Brian Cox, Kiefer Sutherland, Chris Noth, Jason Patric, and Jim Gaffigan are all well established in pop culture for their aforementioned roles.

The combined hype of seeing the late Miller’s beloved play return to the Great White Way and watching a group of well-known actors step into the shoes of some small town men reliving their glory days as high school basketball champions has made the show a buzzworthy production, but does whole equal the sum of its parts?

I won’t keep you in suspense - I felt it was well worth the two-and-a-half hour trip to the Big Apple from Miller’s (and my own) hometown of Scranton, ironically to see a play that’s set in that very city.

If you don’t know the story, members of the starting line-up of a high school basketball team that won a Pennsylvania state championship game visit their coach at his home on the 20th anniversary of their shining moment, as they do each year. This time, the celebratory evening is overshadowed by the coach’s terminal illness and some long-held secrets of the tragically flawed men.

The Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre, located on West 45th Street, provided the small, intimate setting needed for such a production. The setting, a spacious living room with a wide bay window overlooking the porch, immediately reminded me of the local home Miller chose to shoot his 1982 film version in. The casting, after just a few minutes into Act 1, also felt spot on.

Chris Noth easily slinked into the role of shady businessman Phil Romano, acting callously casual when discussing his colorful sex life. He seemed quite natural and relaxed in his delivery and his dramatic monologues.

Jason Patric, son of Miller himself, was able to get plenty of laughs as wandering alcoholic Tom Daley, delivering brutal honesty as entertainingly as he did one-liners. Taking on the role that his father often played himself, there were certainly hints of his dad in his performance, but he often seemed to be channeling more of Johnny Depp’s Jack Sparrow than his Oscar-nominated father.

He brought the performance back when it required it, however, so kudos to him for tackling such a high-pressure role.

Kiefer Sutherland, as Tom’s responsible but overburdened brother James Daley, blew me away, and not in his usual “blowing up bad guys” sort of way. Here’s an actor who has spent years building himself up as your typical action hero, yet he was the most believable everyman as a mousy little junior high school principal. The way Sutherland carried himself added 10 years to his face, and that’s exactly how I would picture the eager-to-please, bespectacled weakling, who is no technically no older than his friends but is often left shouldering the weight of all of their problems.

It was also a privilege seeing Brian Cox completely own the stage as the Coach. Miller himself often said that without a good coach, the rest of the production would fall apart, and there was certainly no danger of that happening here. With a booming voice and physical presence to match, Cox had the charisma to carry his wounded team. Starting out his career in theater and praised for his work with the Royal Shakespeare Company, his stage experience made this performance effortless. He was a joy to watch, and like many of the villainous characters he often portrays, I loved to hate him as his selfish, closed-minded speeches bellowed throughout the theater.

If I was forced to pick a weakest link, which is hard to do with such a cast, I’d say it was Jim Gaffigan as the bumbling Mayor George Sikowski. While I thought he did a fine job portraying an inept politician who has become the butt of everyone’s jokes, he seemed the least natural of all the actors during the first act, as if he was just making sure he delivered all his lines on time and in order. As the play progressed, he seemed much more relaxed in the role. Eventually, I stopped seeing him as the funny man and started feeling sorry for his character’s awkward position.

I’ve read a lot of reviews over the last week that claim the play, which takes place in 1972, is too dated, but I think those critics may be spending too much time in the high-class circles of NYC and not enough in everyday America. Anyone from this area could tell you that things haven’t changed that much since Miller penned that script, and many of the characters’ attitudes are embedded in humanity itself, not the time period.

There is also too much focus in these reviews on the racial slurs and old political references, as if racism has been relinquished since those “ancient” times and political buzzwords like “communism” aren’t still thrown around like daggers at opponents across the aisle. There is a reason this play received the Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 1972 and the New York Drama Critics’ Circle, Drama Desk, and Tony Award for Best Play in 1973 - the symbolism behind its setting, its characters, and their actions remain timeless.Not everything needs a modernized reboot to reach an audience, and if you really don’t believe that, then you probably should move from New York to Hollywood.

The audience, I felt, seemed engrossed by the performances. People laughed at all the right times, and audible gasps could be heard as the men’s verbal scraps led to physical blows. The buzz seemed to be positive during intermission as well as after the show, and Cox, Sutherland, and Patric were generous enough to come out after the performance and sign autographs.

It was the kind of experience that can only happen with NYC theater, so if you have the opportunity to see it during its limited engagement, do so.

Sure, it’s a bit pricey, but it’s not often that you’ll see Hannibal Lecter, “Doc” Scurlock, Mr. Big, “Shakes” Carcaterra, and that Sierra Mist guy all in one place together.

It’s even less often that you’ll be able to forget who they are for a couple hours and just enjoy what they’re creating in front of you.

That Championship Season Review

Jonathan Mandell

The Faster Times

March 11, 2011

Jason Miller’s actual ashes rest in a silver urn on the set of the revival of the play he wrote in 1972, “That Championship Season,” placed there by his son Jason Patric, who plays Tom the drunk in a five-member cast that includes Kiefer Sutherland and Chris Noth.

Miller was 32 years old when he wrote the play, about the 20th reunion of a championship high school basketball team, and there is some irony in his having composed a drama about a group of men whose moment of glory had long since passed. The play won for Miller a Tony Award for Best Play and a Pulitzer Prize for Drama. That same year, Miller was nominated for an Academy Award for his role as the troubled priest in The Exorcist.

Miller died of a heart attack in a bar in Scranton in 2001, the last three decades of his life no match for his early success.

It helps to know about this history - and to spot that urn - to experience the kind of resonance that Patric, who owns the rights to his father’s play, surely meant for a new audience to feel, as the men gather at their coach’s house in nostalgia and break apart in drunken bitterness.

The main problem with “That Championship Season” is that the timeless story of lost glories and regrets is too rooted in the particular time in which it was written.

“Progress?” the coach says more than once. “Nothing changes but the date.”

But the coach is clearly meant to be wrong about this, as he is about everything, especially his anti-Semitic, racist and misogynistic rants.

Things do change. Audiences in 1972 were surely meant to see through the characters’ narrow-mindedness, corruption and self-delusion, and feel good for having done so. But when Coach (as he’s called) sings arias of praise to Senator Joseph McCarthy and Father McLaughlin, the deck now just seems stacked. The red-baiting senator of the 1950’s may still have a handful of defenders, but he and especially the anti-Semitic radio priest of the 1930’s have been judged by history, and dismissed by the public, as bigots and buffoons. Coach, in other words, is a complete schmuck; we get it; how is this interesting?

Crafted differently, the play might have been taken now as a period piece, with its glimpse into 1970’s small town quid-pro-quo life and the then-resistance to the nascent environmental movement. But it is not just the characters in “That Championship Season” who live in 1972; the playwright seems stuck there, arguing on the cusp of changing times for issues we now take as a given.

It is possible that playwrights like David Mamet and Neil LaBute were influenced by Miller’s depiction of coarse male camaraderie, but Mamet et al’s foul-mouthed poetry now overshadows the more conventional cadences of Miller’s play, taking the shock out of it.

Still, if Jason Miller the playwright may not completely hold up, Jason Miller the actor knew how to create meaty roles, and the cast in this first Broadway revival largely takes advantage of them. To the extent that they have star power, it works in their favor - these basketball players saw themselves as stars. Patric does a good job as the drunk with the zingers and in one Spider-Man-like moment when he falls down a long staircase. Chris Noth, best-known as Mr. Big in “Sex and the City” and now as the Chicago pol in “The Good Wife,” demonstrates in his role as Phil, a compulsive Lothario and strip-miner, that New York audiences would profit by seeing him more frequently on the stage. The real revelation here is at-first unrecognizable Kiefer Sutherland, making his Broadway debut as James, a character unlike any you’ve seen him perform before - a stressed-out milquetoast of a junior high school principal lashing out in frustrated ambition.

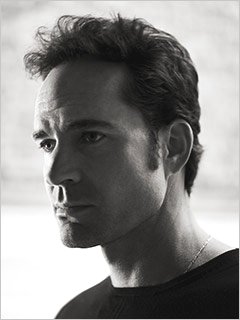

Jason Patric

Image Credit: RICHARD PHIBBS FOR EW

Jason Patric on 'That Champion Season' and why he initially passed on 'The Lost Boys' (twice!)

By Sara Vilkomerson

PopWatch: EW.com

March 10, 2011

Jason Patric, 44, is known for his raw performances in indie films like Rush, After Dark, My Sweet, Narc, and Your Friends and Neighbors — not to mention his early vampy role in The Lost Boys. He’s currently starring in That Championship Season on Broadway, along with Brian Cox, Jim Gaffigan, Chris Noth and Kiefer Sutherland. The Pulitzer-winning play, about members of a winning basketball team reuniting after 20 years, was written by Patric’s late father, Jason Miller, and won a 1973 Pulitzer Prize.

ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY:

Was it a hard decision to be in a play that has such a personal connection for you?

JASON PATRICK:

I guess there was some hesitancy, only because there were a lot of negative associations with it and my whole thing was, would I be able to see it clearly as a piece of material. When I first met [director] Gregory Mosher, it was just about whether I was going to give him the rights to the play - it wasn’t even about me being in it. But I liked what he had to say. I couldn’t ask for better hands for the play to be in - not only dramatically but as far as respect and legacy. I want this to be relaunched as the great American classic that it is.

EW: The play was written and set in 1972, and yet if doesn’t feel dated at all

JP: Isn’t it amazing? It’s as if someone said, I’m going to write about the country today and put it in 1972 so we can have more perspective. It’s insane - it just shows how far ahead of [Miller's] time he was.

EW: Did you change anything from the original at all?

JP: No. Greg said, I want it dead letter perfect. The truth is, you never find great writing so people try to make it more comfortable in their mouths. If you have great writing, there’s a big difference between “anyone” and “anybody,” between a period and ellipse. We get notes if we get something wrong. One day I said, “We won’t have James to kick around anymore,” and I got a note: “It’s ‘Now we won’t have James to kick around anymore.’” It’s very respectful [to the original].

E.W.: You and your castmates really seem to share a special bond

J.P.: I’m glad, we’ve worked very hard on that. Because besides serving the text, you need to be able to believe in that…those little ways, those utterances. I can’t imagine doing a play again for a while - I’m not going to have an experience like this, with these guys, this material. The material is so good, these guys are so dedicated, we go out three or four nights a week together. All of us. We’re like the team.

E.W.: You were instrumental in getting some of the cast together, right?

J.P.: I’ve known Kiefer for 25 years, and and I knew [Chris] Noth a little bit from over the years and I brought him to Greg’s attention and he loved him. It’s a perfect mix. The reality is you need people with a little bit of cache these days [on Broadway], but the truth is you couldn’t hire guys that would be better for these parts. It’s just perfect.

E.W.: You and Kiefer met on the 1987 film The Lost Boys. Do you find it funny that it’s a movie that’s become such a lasting pop culture hit?

I had no money or job at the time, and [director] Joel Schumacher will tell you, I turned that role down twice. I didn’t want to wear teeth and makeup - that’s just not what I wanted to do as an actor. He convinced me. The truth is, if it came out today, it would have made half a billion dollars. It would be Twilight. I went on to do so many other things, that for the first ten years after it [was released], it annoyed me, this Lost Boys stuff, when I felt like I had made some really good, interesting movies. But it’s a part of what I’ve done now, I’m happy with it. I’m glad it’s a touchstone for people.

Kiefer Sutherland And Pals Bring Wattage To NYC

New York News - La Daily Musto

By Michael Musto

March 9, 2011

Newly revived on Broadway, That Championship Season is Jason Miller's Pulitzer-winning 1972 play about a reunion of Pennsylvania high school basketball team members that ends up being a slam dunk into sourness.

The play doesn't totally hold up, mainly because some of its melodramatic revelations now seem too calculated and they just aren't all that shocking anymore (though I have to admit I was surprised by the liberal use of the c word. I should have paid more attention in 1972.)

A starry cast is helping provide some juice, though for patches of it, I felt they were playing the surface emotions without digging between the lines. Plus the direction had some of the play's actions happening too quickly rather than mining them for real human responses and interplay.

But the play garners lots of laughs, features some solid writing, and it picks up steam, especially when Brian Cox gets to scream a lot as the coach who believes in winning at any cost.

As for his costars:

Chris Noth is appropriately smarmy as the amoral businessman who sleeps with people he shouldn't.

Jim Gaffigan is good as the inept and apparently antisemitic mayor.

Kiefer Sutherland--the troubled teacher--was singled out in the Times review as superb, though you might not even notice him for a while; he's a wispy little thing!

My personal fave was Jason Patric as Kiefer's cynical alcoholic brother, who sees the truth in everything going on, even though he's ostensibly falling down a lot.

Jason--whose dad wrote the play--is pretty riveting.

Dad (whose ashes are supposedly watching from an urn onstage) must be loving it.

‘That Championship Season’ Is a Theatrical Slam Dunk

By Bruce Chadwick

History News Network

March 7, 2011

Bruce Chadwick lectures on history and film at Rutgers University in New Jersey. He also teaches writing at New Jersey City University. He holds his PhD from Rutgers and was a former editor for the New York Daily News.

Every year for the last twenty years, four of the five starters for the small Pennsylvania high school basketball team that won the state championship in 1952 gather at their coach’s home to celebrate the victory. At the annual re-union, the coach reminds them, and they remind each other, that they were champions on the court and now, as men approaching forty, they are champions off of it.

They are not.

Jason Miller’s Pulitzer Prize winning play, ‘That Championship Season,’ first staged in 1972, was enormously popular when it debuted and was produced by hundreds of theaters across the country. It was an ensemble acting hit parade and, over the years, produced entertainment superstars such as Paul Sorvino and Danny Aiello.

Now, nearly forty years after its debut, and sixty years after the epic high school championship game, the play, that opened last night, is not stale at all. It has aged like fine wine, or should I say good passing and rebounding, and is a powerful statement about life – and sports. It is also a sharp, perceptive look at sports people, as ‘Lombardi’ was earlier in the theater season. People involved in sports, and those who watch it, learn much about life from it. ‘The Championship Season’ is a big lesson in life, as well as an eye-opening study of sports history.

The drama is one of the best to open in New York this year. It is a success because of the richness of Miller’s script, but also because of the dynamic acting delivered by a quintet of America’s top performers, led by television stars Kiefer Sutherland (‘24’) and Chris Noth (‘Law and Order,’ ‘The Good Wife’).

Noth plays Phil Romano, a wealthy local entrepreneur who is bored with his life and a very lonely man. For excitement, he beds his old teammate’s wife and drives for hours on Pennsylvania highways, then turns around the drives home, his eyes dead while his car races at 140 mph. Noth is superb as the small town businessman. He is very physical, always up and down from the sofa, edgy in his speech, provocative in his language. Sutherland plays James Daley, a junior high principal saddled with five kids, who has gone nowhere in life but has big political plans for himself – shared by no one. Sutherland plays Daley as a low key keg of powder for most of the play, and shines at the end when the keg explodes.

The pair is surrounded by a trio of marvelously gifted actors. Brian Cox is persuasive as the bombastic coach, a lovable character at the start of the play and a despicable one by its end. He bellows and flaps his arms, stalks across the large, handsomely designed living room set and waves his ’52 championship trophy whenever he can, as if it explains his life and the lives of his ‘boys.’

Jim Gaffigan is George Sikowski, the community’s bubble headed Mayor, nicknamed ‘Sabu’ by the newspapers when a circus elephant died in town. The two big issues in his upcoming re-election campaign are that his opponent is Jewish and his opponent’s cousin is a communist. He is as wonderful a dunce as a dunce can be.

Jason Patric plays Tom Daley, a thin, cherubic looking alcoholic who, inebriated most of the play, is the only man who can see the truth and recognize the moral collapse of each of his old teammates. Patric, the son of the playwright, is marvelous as he glides about the stage with a tiny smirk on his face.

The men, on this memorable re-union, have little to show for twenty years of living beyond a hollow silver basketball trophy. They may have won on the court, but they have all failed in life. Director Gregory Mosher does a splendid job of moving his people about the stage and keeping the pace sometimes fast and furious and at other times somber and reflective. His sturdy ensemble cast never fails and creates, moment by moment, a sad portrait of a corroded championship season from long ago.

The history of small town Pennsylvania basketball in the play is nowhere near as complete as it might be. There is electricity in the air in any small town whose high school team plays for a title, as displayed in the movie “Hoosiers.” So, given that, I think they should have updated the film to 2011, looking back twenty years to 1991, in order to get much, much more basketball history into the story.

Basketball was a minor professional sport in ’52, when the NBA was just five years old, scoring was low and crowds were small. By 1991, pro basketball was a huge worldwide sport. It was a sport so big that its stars were all known just by their first names or nicknames: Michael, Pearl, Magic, Bird. If updated, play could connect easier to more fans in the audience. Who connects to 1952? Eisenhower wasn’t even President yet. The update would not eliminate the strong storylines of the play, all still as fresh and troublesome today as they were in 1972.

Each of the men in ‘The Championship Season’ has become a moral wreck in the twenty years since their memorable victory. They drink, chase each other’s wives, cheat on taxes, double-cross each other, lie and pretend to be the pillars of their community, which they are not. It takes the entire re-union night for them to see each other for what they have become. At the re-union they not only rehash the old days, but, in an awkward way, plan Sikowski’s re-election campaign. The coach craftily brings them all on board in the election in the spirit of ‘the team.’

In a final rage, the racist coach, his own terrible secrets and shame revealed, tells his ‘boys’ that “you have to hate to win.” No, you don’t. Hate does not produce victory: hard work, skill and determination produce victory.

Finally, Tom Daley, the drunk, bursts everyone’s memory bubble and blurts out the real reason why they won the championship

The play ends with the weather beaten old coach positioning the men, drinks in hand, together for their annual re-union photo, the championship trophy held proudly in their hands. He tells them, quite sadly, that he doesn’t watch much basketball anymore because it is “no longer a white man’s game” as it was in the 1950s

It is not, coach; now it is an American game.

PRODUCTION: Producers - the Shubert Organization, Robert Cole, Frederick Zollo, the Weinstein Company, Second Chance Productions, others. Set: Michael Yeargan, Costumes: Jane Greenwood, Lighting – Peter Kaczorowski, Sound -- Scott Lehrer. Directed by Gregory Mosher.

Championship Season Star Jim Gaffigan Spills a Boozy Stage Secret: 'We Gargle with Jameson'

Broadway.com

March 7, 2011

From the moment the all-male cast of That Championship Season sets foot on the stage of the Jacobs Theatre, one thing is very clear: These guys are a team. Kiefer Sutherland, Chris Noth, Jason Patric and Jim Gaffigan play one-time members of a high school basketball team gathered at the home of their former Coach, played Brian Cox, 20 years after they won the 1952 state championship. When Broadway.com caught up with them on their opening night, we had to ask: What sort of male bonding goes into forming this tight-knit ensemble?

“I have never hung around with a group of men that consume so much alcohol in my entire life,” joked Gaffigan. No surprise, considering that these guys are on a Broadway bender eight times a week. Enough faux beer and whiskey is consumed during the two-hour show to merit a credit in the program. As such, Gaffigan and Patric have developed a fitting pre-show ritual to get a taste of the real thing. “We gargle with Jameson,” Gaffigan said. “Oh yeah,” Patric agreed, “15 minutes before the show, Jim comes down, we gargle and get our tongues burning and do some vocal exercises.”

Sutherland reserves his cutting loose for the hours post-show. The dressing rooms, he said, don’t have a locker room feel, “but sometimes the bar after does,” the 24 star said with a laugh. As for the pre-show whiskey routine, “I’m not so much a gargler," he cracked, “so I’d probably get myself in trouble.” Team leader Brian Cox was a little more circumspect on what makes this show such a compelling Broadway boys' club. “Testosterone!” he quipped. “A lot of it!”

Will 'The Championship Season' live up to title at Tonys?

By Paul Sheehan

Gold Derby.com

March 7, 2011

In 1972, "That Championship Season" wowed Broadway winning both the Pulitzer Prize for Drama and the Tony Award for neophyte playwright Jason Miller. Nearly four decades on, his son Jason Patric headlines the first Broadway revival of this ensemble drama. Joining him in this memory play about the ill-fated reunion of a high school basketball team with their coach are Kiefer Sutherland, Chris Noth, Brian Cox and Jim Caffigan.

Reviews for this production which opened Sunday were decidedly mixed. Ben Brantley of the New York Times was disappointed to discover that the play is less than the sum of its parts "expressing its intentions loudly, repeatedly and often embarrassingly." Among the actors, he singled out the Emmy-winning "24" star for praise, noting "Sutherland, in his Broadway debut, is the most credible of the lot, quietly conveying a shrunken man poisoned by passivity and resentment."

Scott Brown of New York concurred, dismissing the play as "hopelessly dog-eared" and is "a season or 40 out of date." And he too reserved his praise for Sutherland "who generates the most interesting frisson here, working against his typical screen persona: I want to see him play more angry little men."

New York Daily News scribe Joe Dziemianowicz thought the evening "amounts to two hours of bombast given the full-court press." He thought, "Sutherland makes a credible debut in the unshowy role of a wimpy high school principal with pipe dreams about a political career. Nice to see the '24' star show a vulnerable side."

And for Elysa Gardner of USA Today, "the arguments and diatribes fueling the play seldom encourage reflection, and like real-life drunken banter, can grow tedious." She conceded that "the production is at least a showcase for the theatrical talents of several actors better known for their film and TV work."

That Championship Season, Jacobs Theatre, New York

By Brendan Lemon

FT.com / Arts / Theatre & Dance

March 7, 2011

In a cupboard on the set of That Championship Season, in revival on Broadway, sits an urn containing the remains of Jason Miller, who wrote this play, which premiered in 1972. Jason Patric, the dramatist’s son, who gives an eerily understated performance as an alcoholic, placed the urn there in order to be “in communion” with his father. The metaphor goes further, however: Gregory Mosher, who directed, is essentially poking through the ashes of this drama, seeing if the story can still throw off sparks.

At times the evening does smoulder, especially when Brian Cox is onstage; at others, the repetitive hammering of the story’s main motif - how men go from youthful glory to sad middle age - rings cold. Cox plays the retired Coach, who guided a quintet from Scranton, Pennsylvania, to their state’s 1952 high-school basketball championship. Twenty years later, Coach has reunited four players - George, James, Phil and Tom (Patric) - for supper at his house, a dwelling lined at one end with loaded guns and at the other with portraits of Teddy Roosevelt, Joe McCarthy and John F. Kennedy. The nominal plot involves the re-election of George as Scranton’s mayor. James, now a school principal, is set to run the campaign but Phil, the group’s wealthy member, is considering throwing his support behind George’s Jewish opponent. Coach attempts to arbitrate.

The plot creates scant suspense. Textually, we are less in the land of Big Story than Big Theme: hatred. Coach urges the men to love each other even as he cheerleads for those, such as McCarthy, who fomented division. It is difficult to argue that That Championship Season is dated when hatreds spill forth so readily on the internet, including nostalgia for the days when the White Man was in charge. And yet the drama’s slow pacing, especially in its second act, feels distinctly old-fashioned.

Kiefer Sutherland cannot find much to animate his admittedly mediocre character, James, though that may be the point; Chris Noth, Sex and the City’s Big himself, is so adept at womanising louts that he could have phoned in his performance as Phil. (He doesn’t.) Neither can best the bravura of Cox’s bullish exhortations.

3 out of 5 stars

Kiefer Sutherland in 'That Championship Season': What did the critics think?

David Ng

Culture Monster: Los Angeles Times

March 7, 2011

"That Championship Season" -- the 1972 Pulitzer Prize-winning ensemble drama by Jason Miller -- is receiving its first Broadway revival in a production that is being spearheaded by the playwright's son, the actor Jason Patric. The production, which opened at the Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre on Sunday, is also notable for featuring the Broadway debut of "24" star Kiefer Sutherland.

The play tells the story of a reunion between members of a winning high school basketball team in Scranton, Penn. Their lives have not turned out as they expected and the play explores various shades of disappointment, resentment and betrayal.

"Championship" ran at the Public Theater in New York before transferring to Broadway in 1972, winning the Tony Award for best play. Directed by Greg Mosher, the "Championship" revival features a starry cast that also includes Chris Noth, Brian Cox and Jim Gaffigan.

Patric, who was 6 when the play first opened, recently spoke to The Times about the drama and his father's legacy. In the revival, Sutherland plays the role of a local school principal and Patric plays his frequently drunk brother. Noth takes the role of a businessman who has made a fortune in strip mining, while Cox plays their coach.

How did the critics respond to the revival and Sutherland's Broadway debut? Keep reading to find out...

Ben Brantley of the New York Times wrote that of the production's ensemble cast, "Sutherland, in his Broadway debut, is the most credible of the lot, quietly conveying a shrunken man poisoned by passivity and resentment." He added that Miller's play lacks subtlety and that it expresses "its intentions loudly, repeatedly and often embarrassingly." The Hollywood Reporter's David Rooney wrote that the play "seems past its expiration date," and that this revival production falls flat. He added that the "actors do nail their characters. It's just that their characters are not very interesting." Of Sutherland, he wrote that the actor "brings nervous, wiry intensity" to his role.

Joe Dziemianowiczof the New York Daily News said that the production "amounts to two hours of bombast given the full-court press," adding that the play's themes are presented too blatantly. "Broadway newcomer Kiefer Sutherland makes a credible debut in the unshowy role of a wimpy high school principal with pipe dreams about a political career," wrote the reviewer. "Nice to see the '24' star show a vulnerable side."

Bloomberg's Jeremy Gerard wasn't impressed with the cast, writing that the director "hasn’t coaxed much more than whining and empty bluster" from them.

Elysa Gardner of USA Today wrote that "the arguments and diatribes fueling the play seldom encourage reflection, and like real-life drunken banter, can grow tedious." But the "production is at least a showcase for the theatrical talents of several actors better known for their film and TV work."

New York magazine's Scott Brown found that the play "is hopelessly dog-eared" and that it feels "a season or 40 out of date." Of Sutherland, the critic wrote that the actor "generates the most interesting frisson here, working against his typical screen persona: I want to see him play more angry little men."

Reviewing Brantley on `That Championship Season’

By Paul Moses

dotCommonweal

March 7, 2011

New York Times theater critic Ben Brantley gives a downbeat review today to the New York revival of Jason Miller’s 1972 play “That Championship Season,” about a Catholic high school basketball team’s reunion 20 years after winning the state championship. I haven’t seen the production, so I can’t comment on that. But I think he is off-base in his scathing comments on the Pulitzer- and Tony-award-winning play Miller wrote. According to Brantley:

“Season” appears to have been assembled according to the rule book of Playwriting 101, 1952 edition. Each of the five characters here arrives with a Personality and a Problem, both as conspicuous as a gaudy necktie, and it’s not hard to predict the conflicts that will arise and the symmetry with which they will be presented. (The first act begins and ends with a character holding a rifle.)

Mr. [Jim] Gaffigan plays George Sikowski, the town mayor, who is uneasily facing re-election and is a Buffoon. Mr. [Chris] Noth is Phil Romano, the town Rich Man, whose fortune comes from strip mining, and a Cad. Mr. [Kiefer] Sutherland is James Daley, a school principal and an embittered Little Man who is tired of being small. Mr. [Jason] Patric (who is Mr. Miller’s son) portrays Tom, James’s brother, a Cynical Drunk. They have gathered to celebrate the 20th anniversary of winning the state basketball championship and to honor Coach [Brian Cox], who made them what they are today.

Brantley arrives at the end of the review with the revelation that “That Championship Season” has much in common with Martin Crowley’s 1968 play “The Boys in the Band,” about self-loathing gay men. Hardly original. This, from Clive Barnes in his May 3, 1972 Times review of “That Championship Season”:

This is an enormously rich play. It is one of those strip-all, tell-everything plays in the tradition of “Virginia Woolf” or “Boys in the Band.” These are hollow men, bereft of purpose, clinging to the empty ambition of power. They believe in a past image of America, when Teddy Roosevelt was Emperor and life was a game to be won at all costs. They are morally and intellectually bankrupt. And yet they are also human, recognizable and even, in a way likable.

Barnes called it “the Broadway play of the season,” even before it was on Broadway. It was “gorgeous and triumphant,” depicting the characters’ “long night’s journey into day.” It was “funny, obscene, tragic.” What was formulaic and old-fashioned to Brantley seemed to be the stuff of Greek drama to Clive Barnes.

The underlying theme of “That Championship Season,” in my opinion, is that violence is the dark underside of the American quest for success at any cost - whether in foreign policy or basketball. Brantley seems to find that tiresome. I find it relevant.

'Season' now more like double drivel: '70s hit slips from 'Championship' level

By Joe Dziemianowicz - NY Daily News

March 7, 2011

Time has been unkind to the high-school basketball heroes of "That Championship Season." Twenty years after winning the state trophy, their gleaming lives have all been tarnished by booze, betrayals and backroom deals.

Unfortunately, the years have been just as tough on this 1972 drama by Jason Miller, the writer and actor who starred in "The Exorcist."

Nearly 40 years after winning a Tony and a Pulitzer, the play, which opened last night in a starry revival, amounts to two hours of bombast given the full-court press.

The plot is designed to excite you and incite you with its racist rhetoric, but it's presented so blatantly, you tune out.

The action, set in Nixon-era Pennsylvania, follows four former starters on the dream team who gather to drink (a lot) and relive glory days with their imperious coach. Reveling leads to infighting as - right on cue, in any alcohol-fueled story - harsh truths come out.

Director Gregory Mosher maximized the power of Arthur Miller's "A View From the Bridge" last season, but he's stymied by this less durable work. His staging is lax, and his actors fade into Michael Yeargan's cavernous domestic set. That's no way to treat your cast.

Broadway newcomer Kiefer Sutherland makes a credible debut in the unshowy role of a wimpy high school principal with pipe dreams about a political career. Nice to see the "24" star show a vulnerable side. Comedian Jim Gaffigan, another stage rookie, holds his own as a schlubby mayor who can't run his town or marriage.

At 56, Chris Noth is long in the tooth to be playing a 38-year-old. But the stage and "Sex and the City" alum has an edge that works well as a corrupt businessman. Showing his character's weepy side comes off less well.

Jason Patric (the late author's son), who got soused on Broadway when he played Brick in "Cat on a Hot Tin Roof," hits the bottle again as Sutherland's alcoholic brother. With his eyes permanently squinty and voice filled with silky cynicism, he throws himself into the role — and down the stairs at one point. Patric is well-cast as a former teenage god who's gone to seed, and is the MVP when it comes to giving an interesting performance.

Brian Cox, who's starred on stage in "Rock 'n' Roll" and "Art," portrays the charismatic coach. Cox works hard to make the role believable, but with all of his anti-Semitic, racist and pro-McCarthyism comments, he's a bloated ball of right-wing cliches.

The final moments revolve around a secret behind the hallowed championship season that conveniently comes to light for the first time in 20 years. It raises the issue of the soul-deadening danger of winning at all costs — a worthy theme. But it's one you should communicate through character development, not with a lecture.

You don't have to know basketball to know that this move gets you whistled for a technical foul.

2 out of 5 stars

Theater review: "That Championship Season"

By Robert Feldberg

NorthJersey.com

March 7, 2011

Seeing the revival of "That Championship Season," which opened Sunday at the Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre, you wonder how it won the Tony Award and the Pulitzer Prize after it opened on Broadway in 1972.

The answer, I would guess, is that it opened in 1972 - in an American era of protests, divisions and great political and social upheaval.

The play's relevance to what was happening outside the theater was perhaps more important than its dramatic quality.

We're having troubles now, of course, but they're not quite the same, and that allows the work's flaws to be seen more clearly.

Playwright Jason Miller set his drama in a small city in Pennsylvania's Lackawanna Valley.

Four men who'd been teammates on a state champion high school basketball team 20 years earlier have come to the home of their old coach to celebrate the anniversary.

As the men, alternating between beer and liquor, drink non-stop – it's amazing only one gets really drunk - while gnawing at pieces of chicken, each of their woes surface.

The clownish George (Jim Gaffigan), the city's mayor, is facing a tough reelection battle against a more attractive and modern opponent, whose Jewishness draws the men's contempt.

Phil (Chris Noth) is a rich, jaded businessman whose strip-mining company will face big problems if George's opponent, an ecologist, wins. He's also been sleeping with George's wife.

James (Kiefer Sutherland) is a whiny school principal who wants desperately to be a political force.

Tom (Jason Patric, playwright Miller's son) is James' alcoholic brother, a failed writer who serves as a cynical, one-man Greek chorus.

And then there's the grizzled Coach (Brian Cox), a loud, forceful, positive thinker who idolized Sen. Joe McCarthy and the right-wing radio priest Father Coughlin, dislikes Jews and blacks, and believes in the old virtues of hard work, hating your opponent and winning at any cost.

His former players still adore him. He issues orders on how they should live their lives, and they obey.

If there was resonance 40 years ago in seeing these men as symbolic of the crumbling Establishment and its obedient followers, that no longer exists. Regarded as individual human beings, they don't make much sense.

It's hard to believe that Coach's simplistic, rah-rah exhortations ("All we have is ourselves, boys, and the race is to the quickest, and this country is fighting for her life, and we are the heart, and we play always to win") are enough to keep the men going, and, despite their anger toward one another, as a team of sorts.

The play's final, dark revelation, about how the title game was actually won – and why the team's fifth, and best, starting player didn't show up for the reunion – is underwhelming. Given who Coach is, it's not all that surprising.

"That Championship Season" is uniformly well-acted, and has been directed with physicality and humor by Gregory Mosher.

But the four ex-players never come into compelling focus, even if Gaffigan and Noth do provide some flavor to their characters.

Cox gives his considerable all to the part of Coach, although he, too, doesn't have the material to get much beneath the surface.

The issues at the center of Miller's play are hardly extinct, but they just don't have the juice they once did.

Rebound not worth a shot

By Elisabeth Vincentelli

NYPOST.com

March 7, 2011

The most exciting mo ment in "That Championship Season" comes when Jason Patric's character, Tom, falls down a flight of stairs. For a couple of seconds, you're involved in what's happening: Wow, that was something! Is he OK? How long did he have to rehearse that stunt?

And then it's right back to sleep.

Jason Miller's "That Championship Season" was showered with awards back in 1973: a Tony for Best Play, a Pulitzer Prize. Yet this ham-fisted drama about basketball teammates reuniting 20 years after winning the state high school trophy has aged so badly -- the absent women, for instance, are typically described as whores -- that these accolades seem baffling today.

To resuscitate this play, we needed an A team. But Gregory Mosher's star-studded production -- the cast also includes Kiefer Sutherland, Chris Noth and Jim Gaffigan -- is a train wreck. Actually, that implies some kind of momentum, of which there's none onstage, aside from Patric's tumble.

The four men are celebrating their victory's anniversary at the house of their former coach (Brian Cox), an Archie Bunker-like fount of bigoted idiocy.

Sadly, the long-ago event remains the emotional high point of everybody's life. Sutherland's James is a milquetoast junior-high principal who's also running the re-election campaign of Gaffigan's George, their small town's mayor. Noth's Phil is a cocky businessman while Patric's Tom is entirely defined by his drinking.

Playing against type in his Broadway debut, Sutherland can be subtly effective, but mostly the inert cast doesn't succeed in making the conflicts feel anything but manufactured: Phil sleeps with George's wife and supports George's rival, and the more drinks they all throw back, the testier they get.

Patric -- the playwright's son -- is the lone bright spot as he tries to create an actual character despite having little to work with. Fueled by booze and disillusioned despair, Tom at times looks like one of the bitter gay men in "The Boys in the Band." It's an intriguing bit of subtext that's fun to ponder and helps pass the time.

This tantalizing bit goes nowhere, though: The second-half revelation -- a staple of reunion stories -- isn't about Tom's sexuality but the team's missing fifth man. Like every other plot point, it fizzles out. This isn't "The Big Chill" but "The Big Pill."

In the right hands, "That Championship Season" could be a bitter cautionary tale about prejudice and how achievements can rest on illusions. As it is, the final buzzer can't come soon enough.

That Championship Season

Review by Marilyn Stasio

Variety Reviews

March 7, 2011

A presentation of Robert Cole, Frederick Zollo, Shelter Island Enterprises, the Shubert Organization, James MacGilvray, Orin Wolf, the Weinstein Co., Second Chance Productions, Brannon Wiles, and Scott M. Delman / Lucky VIII of a play in two acts by Jason Miller. Directed by Gregory Mosher.

Tom Daley - Jason Patric

George Sikowski - Jim Gaffigan

James Daley - Kiefer Sutherland

Phil Romano - Chris Noth

Coach - Brian Cox

Since it is now an article of faith that you need big stars to finance a straight play on Broadway, it definitely helps to have Kiefer Sutherland ("24") and Chris Noth ("The Good Wife") on board for this revival of "That Championship Season." Scribe Jason Miller won the Tony, the Drama Critics Circle Award and the Pulitzer Prize for his 1972 drama about the explosive reunion of a high school basketball team 20 years after winning the state championship. But the stars are just as stymied as the rest of the ensemble by the play's schematic structure and transparent characters.

In the postwar years of the 1950s, when we thought better of ourselves as a nation, there was little awareness that those all-American sports ethics of team pride, class loyalty and the will to win could mask such base impulses as bigotry, racism, and the ruthless resolve to triumph at any cost. So there should be something both sad and shocking about the meticulous way that Miller goes about demolishing the reputation of the high school heroes who brought glory to Scranton, Pa., when they won the 1952 state basketball championship.

"Life's a game," Coach (Brian Cox) reminds his "boys" when they gather for their annual reunion at his home (a gloomy museum of dated decor and dusty mementoes in Michael Yeargan's ultra-naturalistic design). In truth, he did more than teach them how to play the game of basketball; he passed on his values for winning at the game of life.

Unfortunately, there are no nuances to the character revelations that Miller makes to illustrate the shabby nature of Coach's civics lessons. The more they drink (and these grown men knock back their drinks with the reckless abandon of teenagers), the uglier their confessions of cruel deeds, immoral behavior, and acts of outright criminal dishonesty.

In breathless bursts of exposition, we learn that George (Jim Gaffigan), the town's joke of a mayor, routinely bends the law for cronies; that Phil (Noth), an unscrupulous businessman, made his fortune from strip-mining; that James (Sutherland), a high-school principal, has been corrupted by political patronage; and his misanthropic brother Tom (Jason Patric) is a hopeless drunk.

Along with all his other lessons in manhood, Coach also passed on (in the most vile language) his hatred of women, blacks, Jews, "fellow travelers," and anyone else who dares challenge his boys' supremacy or deny them the right to win this dirty game on their own terms.

But the players on this team have no individuality beyond the central character defect that defines each one of them. And Coach's rallying cry -- "We are the country, boys" -- is a pretty blunt metaphor for their collective identity.

With so little dimension to the characters, it's hard to fault the thesps for their competent but superficial perfs. Tom's drunken despair gives Patric (the playwright's son) a more sympathetic character hook. And the sheer breadth of Phil's sins gives Noth more sides to play.

But what this ensemble really lacks is team identity. Watching these bad boys turn on one another loses impact because helmer Gregory Mosher fails to establish the sense of easy intimacy that only comes from knowing someone your whole life.

As a group, the boys don't have the size or the soft, bloated look of athletic bodies gone to seed in early middle age. It doesn't help that the rigid division of furniture in Coach's overstuffed living room offers nowhere for them to sit together as a group to drink, talk, and horse around. But the main thing that's missing is the sound of laughter that lets us know what kind of team they were before the rot set in.

Set, Michael Yeargan; costumes, Jane Greenwood; lighting, Peter Kaczorowski; sound, Scott Lehrer; fight director, Rick Sordelet; production stage manager, Jane Grey. Reviewed March 2, 2011. Opened March 6. Running time: 2 HOURS

Stage Dive: The Faded Glory of That Championship Season

By Scott Brown

New York Mag.com: Vulture

March 6, 2011

The five-man squad onstage in That Championship Season is a not unimpressive bunch, a Hollywood casting director’s “dream team” of sorts: If not quite the Jordan-Magic-Bird miracle of the ’92 Olympics, they’re certainly within a halfcourt shot of the 2000 Carter-Hardaway-Garnett incarnation. Kiefer Sutherland, Chris Noth, Jason Patric, the comedian Jim Gaffigan, and the great Brian Cox have united to resuscitate Jason Miller’s brined-in-testosterone 1972 Pulitzer-winner, a vicious little Watergate-era object lesson in bonding and betrayal, bad leaders and blind followers, feet of clay and hearts of stone. It’s the anti-Lombardi. N.B.: That doesn’t make it good.

These famous (and semi-famous) names are all playing the game they were recruited to play: Unlike a lot of boldface screen personalities slumming on Broadway, these guys actually listen to each other and, for the most part, throw their signals well. More than once, they manage to produce the illusion that there’s a real barnburner going on. But their playbook, I’m afraid, is hopelessly dog-eared. Miller (who was Patric’s father, and died in 2001) certainly knew a thing or two about the infernal side of the American drive to Win It All. (He channeled some of that demonic intuition into his best known role as an actor: Father Damien Karras in The Exorcist.) But today, we’re all thoroughly drilled in the hazards of team spirit, and in its ugly undercurrent, the oh-so-useful hatred of The Other Side. That Championship Season, a shocker in 1972, is a season or 40 out of date, its fire-bell-in-the-night philippics now playing as crude Tourettic barks.

Cox, unluckily, is charged with most of the barking. He plays Coach, a bulldog in a Gordon Liddy mustache. He’s an old-school Pennsylvania Catholic Democrat, or what we’d today call “a Republican.” Still the guiding cynosure in the lives of his now-grown championship basketball team—none of whom ever recovered from the dubious glories of their win at State—Coach exerts all the power of a childhood seducer. (The Catholic sex-abuse scandal can’t help having a distorting effect in how we view Coach’s hold on these boys; director and Mamet vet Gregory Mosher deals with it only fitfully, and ultimately, there’s not much he can do.) The coach is now running the mayoral reelection campaign of George (Gaffigan), a doughy point guard turned malleable politician. He’s also running the school board via James (Sutherland), a priggish little monster visibly vibrating with neutered apoplexy. (Sutherland generates the most interesting frisson here, working against his typical screen persona: I want to see him play more angry little men.) Coach even holds sway in the business community, via the coal magnate Phil (Noth, a stage natural who knows how to anchor a scene). Phil’s a strip miner with a taste for stag films and other people’s wives. “Number one threat to the environment, they called me that,” he fumes. “The stupid bastards don’t realize, you can’t kill a mountain. Mountains grow back.” They don’t, of course, and neither do reality-pruned male egos. Living proof of this is presented in the wobbly form of sad, sodden Tom (a becomingly rubber-limbed Patric, playing his one note well), the play’s appointed drunk/prophet.

For a while, the play sways along with Tom’s jolly oblivion, all-too-systematically exposing the Coach’s teachings as the reactionary death rattle of a demographic that’s slowly being stripped of its unchallenged supremacy: Jews, blacks, and women bear the brunt of Coach’s wrath. “It’s not a white man’s game anymore,” he finally admits. And his team’s in tatters: Terrible (if hardly surprising) revelations pit the boys against each other, and hate, as a binding force, has a way of backfiring. Our collective pop-consciousness knows this lesson well, and Miller—who certainly wrote some knuckly dialogue back in the day—was one of our original teachers. Still, he didn’t really build this play to last. The act break, capped by a great zinger from Patric, has the feel of a Dukes of Hazzard freeze. Mosher has conjoined the second and third acts, creating a highly nonstandard structure for a Broadway show: a brief, breezy first followed by an interminable second. The show’s prolapsed aft end has no story to drive it, and the characters simply pace their ruts over and over: They can’t change, or grow, or learn, or develop in any way, because Miller won’t let them. They’re all fragile exhibits in his can-you-believe-these-honkeys freakshow, the star of which is Coach, whose roaring Father Coughlin monologues dominate the play’s shapeless, grating final hour. Sadly, we can believe these honkeys, and, with its distinct cologne of embalming fluid, That Championship Season, far from alarming our social immune systems, gives us the opposite impression: that these little monsters are contained behind theatrical Plexiglas, safely encased in the past. Nothing could be further from the truth. We can see the old four-corners offense coming for a Pennsylvania mile.

At the Jacobs Theatre, 242 West 45th Street.

That Championship Season: Review

By David Finkle

TheaterMania.com

March 7, 2011

If the demise of Fox's 24 is what has freed Kiefer Sutherland to finally make it to Broadway -- in Gregory Mosher's immaculately gritty revival of Jason Miller's award-winning 1972 drama That Championship Season, now at the Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre -- then those die-hard series fans should much less deprived. Aided by co-stars Brian Cox, Jim Gaffigan, Chris Noth, and Jason Patric, the cast brings this emotinally charged drama to urgent and abrasive life.

The play is set during the 20th reunion of a championship Pennsylvania high school basketball team (at a time when relatively short men could compete victoriously), where the group engages in alcohol-aided bonding at the home of their now-retired and off-handedly bigoted coach (Cox). While most of the men still live in the same town -- and are interconnnected in their daily lives -- during the few crucial hours they spend together on this fateful night, both old and new secrets force their way to glaring light.

Indeed, it's instantly apparent as the action inexorably unfolds in Michael Yeargan's version of an aging Victorian living-room that the affability on hand will soon falter. Moreover,there will be no let-up until the private miseries every character maladroitly harbors is exposed. When going after his quintet of protagonists -- and frequently contriving awkwardly to get them off stage so others can talk about them -- Miller is also so intent on unleashing convictions about the All-American American male having feet of clay that he hammers relentlessly at it.

While Miller refused to cover his iron fist with a velvet glove, he has nevertheless provide the actors to hone their sharpened craft Wearing heavy-rimmed glasses and, initially, a pork-pie hat, Sutherland is totally convincing as James, a high school teacher haunted by the belief he's become anonymous. As his booze-addicted brother Tom, the brilliant Patric (the son of playwright Miller) serves up so many small quirks that it's impossible not to watch him moment by moment for what he'll do next.

Noth is impresive as Phil, a ruthless businessman grabbing all the loot he can running a strip-mining outfit. (Whether he is ideal casting as an Italian Lothario may be in question.) Gaffigan gets the dull, baffled George, the town's ineffectual mayor, absolutely right; and Cox brings off his usual theatrical-magic trick as the coach -- and not least when pulling up his vest and shirt to expose the angry-red vertical scar he carries from recent and not necessarily successful surgery.

Miller meant the play's title to be ironic, but the opportunities the work offers actors like these is definitely a championship effort.

'That Championship Season,’ With Kiefer Sutherland

By Ben Brantley

NYTimes.com

March 6, 2011

“That Championship Season,” Jason Miller’s portrait of morally bankrupt men remembering their glory days as a high-school basketball team, was never what you would call a shy play. Like its liquored-up, confession-prone characters, this award-laden 1972 drama states its intentions loudly, repeatedly and often embarrassingly.

To give it the sort of extroverted, star-swollen revival that opened on Thursday night at the Bernard B. Jacobs Theater is akin to handing Ethel Merman a megaphone. Even when voices are pitched low, Gregory Mosher’s production — which features Kiefer Sutherland (late of television’s “24”), Chris Noth, Jason Patric and Jim Gaffigan as the grown-up teammates and Brian Cox as their esteemed former coach — seems to be shouting at you. This is the sort of work in which the jingoistic old Coach says to his former players, “We are the country, boys.” And though it’s still early in the evening, your instinct is to groan, “Oh, Coach, you don’t need to tell us that.”

Being equated with the United States is not a compliment, according to Mr. Miller, who died in 2001. “That Championship Season,” which was first staged at the Public Theater before moving to Broadway, made its debut on the eve of the Watergate scandal. And it is steeped in the smell of disgust with red-white-and-blue corruption in the age of the Vietnam War. That aroma had been hanging thickly over film and theater since at least the mid-1960s, in movies like “Joe” and “Easy Rider” and plays from Edward Albee, Jean-Claude van Itallie and David Rabe, among others.

What distinguished “Season” from such antecedents - and may account for its copping both the Pulitzer Prize and the Tony Award for best play - was its formal old-fashionedness. Though littered with four-letter words, “Season” has a clean, mechanical structure in which revelations arrive like well-run trains at a station. Theatergoers who felt hip enough to be lambasted for being middle-class sell-outs but not hip enough for the experimental ambiguities of an Albee play could sit back and enjoy American traditionalism being attacked in the traditional style to which they were accustomed.

Mr. Mosher, who oversaw the superb revival of Arthur Miller’s “View From the Bridge” last season, isn’t about to undermine this drama’s perverse comfort factor. As designed by Michael Yeargan, the living room in which the play is set gleams with polished, dark-wood affluence. This is Coach’s lair in the Lackawanna Valley in Pennsylvania, and it looks like a carefully preserved homestead on a historic tour.

I’m assuming this is to underline the idea of this play’s characters as museum pieces, members of a breed on the verge of extinction in a rapidly changing country. (Though the year is 1972, Mr. Cox’s Coach has been made up to look like his idol, Teddy Roosevelt, whose portrait hangs on the wall.) But all this fustiness has the side effect of drawing attention to the datedness of the play itself.

And make no mistake. “Season” appears to have been assembled according to the rule book of Playwriting 101, 1952 edition. Each of the five characters here arrives with a Personality and a Problem, both as conspicuous as a gaudy necktie, and it’s not hard to predict the conflicts that will arise and the symmetry with which they will be presented. (The first act begins and ends with a character holding a rifle.)

Mr. Gaffigan plays George Sikowski, the town mayor, who is uneasily facing re-election and is a Buffoon. Mr. Noth is Phil Romano, the town Rich Man, whose fortune comes from strip mining, and a Cad. Mr. Sutherland is James Daley, a school principal and an embittered Little Man who is tired of being small. Mr. Patric (who is Mr. Miller’s son) portrays Tom, James’s brother, a Cynical Drunk. They have gathered to celebrate the 20th anniversary of winning the state basketball championship and to honor Coach, who made them what they are today.

Within the show’s first 10 or 15 minutes these guys have casually linked themselves to unsavory activities that include graft, bribery, political patronage and sex (en masse) with a retarded girl in high school. Drinking copiously and slurring ethnic slurs, they are obviously not contented souls. But they have the untarnished memories of that championship season, and they have each other. Right? As Coach (whose personal heroes include both President John F. Kennedy and Senator Joseph McCarthy) tells them, it’s teamwork that keeps this country great in an era of dissension.

That myth unravels so early that much of “Season” is a matter of marking time and waiting for the big symbolic moments, like when somebody throws up into the silver victory cup. In the meantime, each character (except Tom, who mostly just snipes at the others) has a tremulous speech in which he reveals how sad he is. (Here’s George in Act II: “You think the old clown doesn’t have deep feelings, huh?”)

It’s not easy making such lines sound fresh. Mr. Cox, Mr. Noth and Mr. Patric all overact, though each overacts in his own special (and sometimes entertaining) way. Epicene and bizarrely Southern, Mr. Patric summons the spirit of Tennessee Williams’s alcoholic Brick (whom he played in the 2003 Broadway revival of “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof”). Mr. Cox, a first-rate British stage actor, here takes on the persona of a 19th-century barnstormer like Edwin Booth. Mr. Noth is just plain hammy.

Best known as a stand-up comic, Mr. Gaffigan is perhaps a shade too understated as the clownish mayor. Mr. Sutherland, in his Broadway debut, is the most credible of the lot, quietly conveying a shrunken man poisoned by passivity and resentment.

Mr. Mosher’s direction is self-consciously stagy (you can imagine the blocking directions penciled into each actor’s script), and there is little natural flow or friction among the performances. (There’s one terrific, atypical moment in which the brothers, Tom and James, signal hostility by throwing a basketball at each other.)

This is strange, since Mr. Mosher made his name with impeccably synchronized ensemble productions of plays by David Mamet. Given the participation of this director and this all-male cast, I was looking forward to “Season” as a sort of Mametian testosterone bath. At some point, though, I realized that it wasn’t a play by Mamet that “Season” recalled, but “The Boys in the Band,” Mart Crowley’s 1968 drama of unhappy homosexuals.

I mean, think about it. Both plays present an ostensibly supportive group of friends who, over the course of many drinks, turn on one another and segue into anguished confessions. Heck, there’s even an “I dare you to make that call” telephone scene in both plays. And each ends with characters revealing their profound discontent with their existential conditions. In “Boys,” of course, that’s being gay. The boys of “Season” are afflicted by the disease of being American, and as this play ponderously presents it, there’s no cure in sight.

THAT CHAMPIONSHIP SEASON

By Jason Miller; directed by Gregory Mosher; sets by Michael Yeargan; costumes by Jane Greenwood; lighting by Peter Kaczorowski; sound by Scott Lehrer; fight director, Rick Sordelet; production stage manager, Jane Grey; production manager, Aurora Productions; general manager, Lisa M. Poyer. Presented by Robert Cole, Frederick Zollo, Shelter Island Enterprises, the Shubert Organization, James MacGilvray, Orin Wolf, the Weinstein Company, Second Chance Productions, Brannon Wiles and Scott M. Delman/Lucky VIII. At the Bernard B. Jacobs Theater, 242 West 45th Street, Manhattan; (212) 239-6200; telecharge.com. Through May 29. Running time: two hours.

WITH: Brian Cox (Coach), Jim Gaffigan (George Sikowski), Chris Noth (Phil Romano), Jason Patric (Tom Daley) and Kiefer Sutherland (James Daley).

Championship Season has not aged well

By David Rooney

March 6, 2011

NEW YORK (Hollywood Reporter) - A drama about the bitter recriminations of a generation of men stung by the reality of their diminished promise and feeling let down by both their leaders and their peers should strike chords in this rudderless age of epidemic disillusionment.

So why does this deluxe Broadway revival of such a celebrated play as "That Championship Season" fall flat?

Returning to Broadway after a decade's absence, director Gregory Mosher last season reminded us what a gifted sculptor of ensemble drama and excavator of textual depths he can be in his superlative staging of Arthur Miller's "A View From the Bridge." This time, the director plants his actors on Michael Yeargan's handsome set and drills them through their paces. But they fail to get under their characters' skin or the audience's in a play that seems past its expiration date.

That's an ungratifying opinion to report given the poignant back-story. First produced to critical acclaim in 1972, the play won both the Pulitzer and Tony that season, the same year playwright Jason Miller was nominated for an Oscar for his supporting role as Father Damien Karras in "The Exorcist. Like his characters, who reunite once a year to revisit a shining moment of their youth unequaled in later life, Miller's subsequent achievements were more modest. He died of a heart attack in 2001, aged 62.

Miller's son, Jason Patric, controls rights to the play and was instrumental in bringing together elements of this production, giving himself the role of cynical alcoholic Tom Daley. The evident intention to honor his father's memory makes the play's ineffectiveness even sadder.

Tom is one of four players from a high-school basketball team that won the Pennsylvania state championship in 1952. They have gathered at the home of their former coach (Brian Cox) every year since to relive the glory. Their enduring fondness for the coach is perhaps because he's the one person who still sees them in terms of their potential, while the ailing coach clings to the belief that his training built the boys for success.

Those comforting self-deceptions are harder to maintain now that the lads are pushing 40 and racking up disappointments. "It's like half-time," says Tom with typical offhand derision. The familiar theatrical truth serum of free-flowing booze brings lies, betrayals and ugly admissions bubbling to the surface, while the key absence of a fifth player ultimately exposes the hollowness of that long-ago triumph.