|

1636:

Hartford's

Founding English Settlement:

Dutchman Adrien Block explored the CT River in

1614, and established a trading post in Hartford in 1633,

following the European epidemic that destroyed 90% of the

native population along the Eastern Seaboard of North and South

America. The Suckiaug (a clan of the Sequins) inhabited

the banks of what is now the Park and Connecticut rivers and

moved further inland for the winter.

Englishman The Rev. Thomas Hooker was the co-founder of his church in

Cambridge, MA in 1632. Four years later, Hooker joined the

two advance parties with more than 100 English colonists, including

wives, children, servants, wagonloads of property, a hundred and

twenty cattle and foul. He came in part to establish an

English beachhead in Connecticut against the Dutch, and to establish his own

flavor of Puritanism (Calvinism, Congregationalism). The

colonists were looking for large unsettled spaces, necessary

for becoming prosperous. They intended to earn their living raising cattle, so

large portions

of land was needed for grazing. Hooker renamed the settlement after Hertford,

England. An English patent gave the colonists the

right to settle the land between Windsor and Wethersfield, all the

way to the Pacific Ocean. The patent also gave the colonists the

right to govern themselves. The colonists purchased their

parcels from the Suckiaug (see map below), who were happy to have

an ally against the Pequot who had recently attacked and taken

their land in the South Meadows.

The settlement map shows about 48 original English

property owners. These house lots of approximately 2 acres were located between

what is now Main Street and the old Front Street. Lots in

the Little Meadow were for gardens and grazing, distributed

according to need: from 1/6 of an acre to 2.5 acres. Later

lots for farming and grazing were allocated in the north and

south meadows - some as large or larger than 40 acres. The Little River (now the Park River) divided the city north and

south. Dutch and Native American property are also shown.

1637

- The Pequot War

The settlement of Hartford occurred amidst the Indian wars between the

Pequot and Mohawk (who wanted to trade exclusively with the Dutch), and

the Pequot and Dutch and

English - each vying for control over Connecticut. The war

was triggered in 1634 by the Dutch sending a dead Pequot sachem,

despite the tribe's delivery of the ransom demanded by the Dutch

for their leader. Not making the distinction, the Pequot

retaliated by attacking two English ships and killing their crew

and captains, one a blackguard, and the other a respected

trader. A Massachusetts colony captain killed 14 Pequot

and burned two villages. The Pequot besieged Saybrook that

fall and winter and killed anyone outside of the fort.

In April, 1637, another tribe with Pequot help attacked

Wethersfield, killing six men and three women and

abducting two adolescent girls. The towns lost about 30

settlers in all. As a result, the court in Hartford

declared war against the Pequot on May 1, 1637, just one year

after the settlement's formation. The three towns sent

Captain John Mason with a militia of 90 and 70 Mohawk who joined

with 20 from Fort Saybrook to retaliate. Several hundred

Narragansett joined Mason as well. Thinking the English had

missed their forted village at Mystic, most of the Pequot men

left to attack Hartford. Mason ordered the Pequot

enclosure burned with all the inhabitants inside. They

were mostly women, children and older men, who were killed on

Mason's order as they tried to escape. Having no tribal

allies, the remaining Pequot faced Mason's troops in what is now

Fairfield. Mason killed about 2/3 of the Pequot men,

letting a few hundred women and children free. Possibly 80 men

escaped with their leader, Sassacus, heading for the Mohawk in

New York. The Mohawk sent Sassacus' scalp to Hartford, as

a symbol of friendship with the Connecticut Colony. In the

end, the colonists called for the near extinction of the Pequot,

divvying up their land with the Mohawk and Narragansett,

enslaving the remaining members and banning their

language. By 1666, the few who survived were assigned

reservations in Connecticut Colony. Today, you can see a

film reenactment of the Mystic Massacre at the Mashantucket

Pequot Museum at the tribe's famously profitable casino in

Connecticut.

After the defeat of Pequot in 1637, the Suckiaug conveyed

extensive land (currently Hartford and West Hartford) to the English

who reserved land in Farmington for them. While the Colonists

of 1636 paid the tribes for the land, the 1637 conveyance was

considered a gift until 1670 when the members of the

tribe were paid for the conveyance. The last descendent of

the native

property owners in Hartford's South Meadows sold his land in

1723.

The

Dutch in Hartford, 1636

Despite the fact that the Dutch claimed ownership

of the land south of the Little (Park) River, the English

claimed a prior authority when they arrived, and boldly parceled out land

there that had not been developed by the Dutch (see map). After 15

years of petty crimes between the Dutch and English in Hartford (missing cattle,

trampled crops, fences built and torn

down, etc.), arbiters of the Dutch and English determined that

the status quo should remain. Six years later, in 1656, a

treaty gave the Dutch land to the English.

Hartford

- Site of the First

'Witch' Executed in America

In 1642 witchcraft became a capital crime in Connecticut.

On May 26, 1647 Alse Young of Windsor was tried for witchcraft

and hung in Hartford on the green that is now The Old State

House square. The next year, Mary Johnson of Wethersfield,

already whipped twice for theft, confessed to murdering a child

and 'licentiousness'. Her baby, born during her five and a

half months in jail, was raised by the jailor's son. Three

years later, a Wethersfield couple was executed, and a Windsor

woman three years after that. In 1662 nine Hartford men and women

were tried for being under the influence of the devil - three were

executed, the last of a total of eight such executions in

Connecticut - all concentrated in this 15 year period. At

the center of the group of nine was Rebecca Greensmith,

repeatedly seen dancing and drinking with her friends on what is

now South Green. Her husband Nathaniel had been convicted

of theft twice, censured for lying and accused of building his

barn on common land. Rev. John Whiting described Mrs.

Greensmith as "a lewd, ignorant and considerably aged

woman". A small child in delirium accused the

group. The child's death was followed by speculations of

the neighbors. The accused were interviewed and arrested.

A daughter of John Cole had fits that, she said were caused by

Mrs. Greensmith. More arrests followed. Of the nine,

the Greensmith's and one of their friends, Mary Barnes of

Farmington were hung. The others fled or were

released. Elizabeth Seager, accused of adultery, spent a

year in jail. This was thirty years before the infamous

Salem witch trials. Witchcraft was last listed as a

capital crime in Connecticut until 1715.

The

West End 1636 - 1697:

The West End would have been outside of the footprint of the

Hartford Settlement in 1636, but once the Suckiaug conveyed the

land that is now Hartford and West Hartford in 1637, it became

part of the settlement. The identification of land

generally flowed in order from the Connecticut River

westward. However, for some unknown reason an area known

as Bridgefield (most of the current West End) was identified

well before areas to the east of it, and was not part of a

plantation division - the usual manner of apportioning

land.

Bridgefield was a rectangular area identified at

some point before 1651. It stretched from the

current Park River for six tenths of a mile west, a few blocks

past what is now the Hartford city line at Prospect

Avenue. Bridgefield stretched from what is now Capital

Avenue to about Elizabeth Street. The current Farmington Avenue

ran down the middle. In 1697 divisions were made here for

9 of the original settlers: Haynes, Hooker, Goodwin, John Allyn,

Talcott, Wadsworth, Goodman and Lewis. On average each

would have received parcels over 30 acres. Since each

would also have received large amounts of land for grazing when

they settled in 1636, presumably the West End remained wooded

for quite some time.

Most of the land here was initially heavily

wooded. Typically the progression was: cleared for grazing

land, and eventually used as farm land before a 'suburban' home

was built on a large parcel, or perhaps immediately subdivided

into building lots which were typically 1/4 to 1/3 of an

acre. Over 350 years, this was also the progression of

development in the West End.

Click map for enlargement.

Original plates combined - from: The

Colonial History of Hartford on-line

1636:

Hartford's

Founding English Settlement:

Click map for enlargement.

Original plates combined - from: The

Colonial History of Hartford on-line

(added notations in brown)

The

Beginning of European Settlement

Dutchman Adrien Block explored the CT River in

1614, and established a trading post in Hartford in 1633,

following the European epidemic that destroyed 90% of the

native population along the Eastern Seaboard of North and South

America. The Suckiaug (a clan of the Sequins) inhabited

the banks of what is now the Park and Connecticut rivers during

the summer but moved further inland for the winter.

Englishman The Rev. Thomas Hooker was was a charismatic religious

leader with a large following in England. He so threatened at

least three British bishops, that he just escaped arrest when he

left for the Netherlands. He concluded that only in New

England would they be allowed to practice religion their

way. In 1633, at the age of 48, he joined many of his

followers in Newtown (Cambridge), in the Massachusetts Bay

Colony. He found himself at odds with the Boston

leadership that enforced all citizens to be members of the

church or be banished (to the wilderness, and near certain

death). Hooker argued that non-church

members should be able to be citizens.

Hooker joined his two advance parties with more than 100 English colonists, including

wives, children, servants, wagonloads of property, a hundred and

twenty cattle and foul. He came in part to establish an

English beachhead in Connecticut against the Dutch, and to establish his own

flavor of Puritanism (Congregationalism) - without mandatory

membership in the official church. The

colonists were looking for large unsettled spaces, necessary

for becoming prosperous. They intended to earn their living raising cattle, so

a large amount of land was needed for grazing. Hooker renamed the settlement after Hertford,

England. An English patent from Hooker's friend Lord

Warwick gave Thomas Hooker's group the

right to settle the land between Windsor and Wethersfield, all the

way to the Pacific Ocean. (These two other English 'River Towns'

had been settled the year before with a group from Plymouth and

another from the Massachusetts Bay Colony.) The patent, no

longer in existence, also gave the colonists the

right to govern themselves.

The settlement map shows 50 original English

property owners in Hartford. Most of them were part of

Hooker's congregation, many highly educated, and all seeking land

to raise cattle and make their family fortunes. Most of their

names are familiar to us 350 years later. These house lots of approximately

two acres were located between

what is now Main Street and the old Front Street and along Charter

Oak Avenue. The the first and second meeting houses stood

on the site of the Old State House. (About 100 years

later, Center Church was moved to its present location on Main

Street and still rings the original bell cast in England in 1633.) Lots in

the Little Meadow were for gardens and grazing, distributed

according to need: from 1/6 of an acre to 2.5 acres. Later,

lots for farming and grazing were allocated in the north and

south meadows - some as large or larger than 40 acres. The Little River (now the Park River) divided the city north and

south into two separate plantations. The colonists purchased their

parcels from the Suckiaug (see map above), who needed

an ally against the Pequot who had recently attacked and occupied their

area in the South Meadows. The Dutch also claimed the

south side of the Park River. They had purchased their land

from the Pequot.

1637

- The Pequot War

The settlement of Hartford occurred amidst the Indian wars between the

Pequot and Mohawk (who wanted to trade exclusively with the Dutch), and

the Pequot and Dutch and

English - each vying for control over Connecticut. The war

was triggered in 1634 by the Dutch killing a Pequot sachem

boarding their ship to establish trade. Despite the tribe's delivery of the ransom demanded by the Dutch,

the Dutch sent their sachem home dead. Not making the distinction, the Pequot

retaliated by attacking two English ships and killing their crew

and captains, one a blackguard, and the other a respected

trader. A Massachusetts colony captain killed 14 Pequot

and burned two villages. The Pequot besieged Saybrook that

fall and winter and killed anyone outside of the fort.

In April, 1637, another tribe with Pequot help attacked

Wethersfield, killing six men and three women and

abducting two adolescent girls. The towns lost about 30

settlers in all. As a result, on behalf of the three river

towns and the fort at Saybrook, the court in Hartford

declared war against the Pequot on May 1, 1637, just one year

after the settlement's formation.

The three towns sent

Captain John Mason with a militia of 90 and 70 Mohawk who joined

with 20 from Fort Saybrook to retaliate. Several hundred

Narragansett joined Mason as well. Thinking the English had

missed their forted village at Mystic, most of the Pequot men

left to attack Hartford. Mason ordered the Pequot

enclosure burned with all the inhabitants inside. They

were mostly women, children and older men, who were killed on

Mason's order as they tried to escape the fire. Having no tribal

allies, the remaining Pequot faced Mason's troops in what is now

Fairfield. Mason killed about 2/3 of the Pequot men,

letting a few hundred women and children free. Possibly 80 men

escaped with their leader, Sassacus, heading for the Mohawk in

New York. The Mohawk sent Sassacus' scalp to Hartford, as

a symbol of friendship with the Connecticut Colony. In the

end, the colonists called for the near extinction of the Pequot,

divvying up Pequot land with the Mohawk and Narragansett,

enslaving the remaining members who wished to live and banning their

language. By 1666, the few who survived were assigned

reservations in Connecticut Colony. Today, you can see a

film reenactment of the Mystic Massacre at the Mashantucket

Pequot Museum at the tribe's famously profitable casino in

Ledyard, Connecticut.

After the defeat of Pequot in 1637, the Suckiaug conveyed

extensive land (currently Hartford and West Hartford) to the

Hartford settlement. It is said this was in gratitude for the

protection they received from the English. In return, land

was reserved in Farmington for the Pequot. While the Colonists

of 1636 paid the tribes for the land, the 1637 conveyance was

considered a gift until 1670 when the members of the

tribe were paid for the conveyance. The last descendent of

the native

property owners in Hartford's South Meadows sold his land in

1723.

The

Dutch in Hartford, 1636

Despite the fact that the Dutch claimed ownership

of the land south of the Little (Park) River, the English

claimed a prior authority when they arrived, and boldly (and

immediately) parceled out land on the south side that had not been developed by the Dutch (see map). After 15

years of petty crimes between the abutting Dutch and English in Hartford (missing cattle,

trampled crops, fences built and torn

down, etc.), arbiters of the Dutch and English determined that

the status quo should remain. Six years later, in 1656, a

treaty gave the Dutch land to the English.

The

Fundamental Orders, 1639

“The foundation of authority is laid firstly in the free

consent of the people.” These most famous words of

Thomas Hooker's sermon of 1638 would be central to the

Fundamental Orders, adopted by a vote of the freemen of

Hartford, Windsor and Wethersfield in Hartford in1639. The

document does not refer to any government or power outside of

Connecticut itself. It did not limit the vote to members of

Puritan congregations. This appears to be the first written

constitution in the Western tradition which created a government

based on the vote of the citizens, and it is easily seen to be the prototype of our

Federal Constitution, adopted exactly one hundred and fifty

years later.

Hartford

- Site of the First

'Witch' Executed in America

In 1642 witchcraft became a capital crime in Connecticut.

On May 26, 1647 Alse Young of Windsor was tried for witchcraft

and hung in Hartford on the green that is now The Old State

House square. This was the first ever execution for

witchcraft in America. The next year, Mary Johnson of Wethersfield,

already whipped twice for theft, confessed to murdering a child

and 'licentiousness'. Her baby, born during her five and a

half months in the Hartford jail, was raised by the jailor's son. Three

years later, a Wethersfield couple was executed, and a Windsor

woman three years after that. In 1662 nine Hartford men and women

were tried for being under the influence of the devil - three were

executed, the last of a total of eight such executions in

Connecticut - all concentrated in this 15 year period.

At

the center of the group of nine was Rebecca Greensmith,

repeatedly seen dancing and drinking with her friends on what is

now South Green. Rev. John Whiting described Mrs.

Greensmith as "a lewd, ignorant and considerably aged

woman". Her husband Nathaniel had been convicted

of theft twice, censured for lying and accused of building his

barn on common land. A small child in delirium accused the

group before she died. The child's death was followed by speculations of

the neighbors. The accused were interviewed and arrested.

Then, a daughter of John Cole had fits that, she said were caused by

Mrs. Greensmith. More arrests followed. Of the nine,

the Greensmith's and one of their friends, Mary Barnes of

Farmington were hung. The others fled or were

released. Elizabeth Seager, accused of adultery, spent a

year in jail. This was thirty years before the infamous

Salem witch trials. Witchcraft was last listed as a

capital crime in Connecticut until 1715.

The

West End 1636 - 1697:

The West End would have been outside of the footprint of the

Hartford Settlement in 1636, but a year later the Suckiaug

conveyed the

land that is now Hartford and West Hartford to the

colonists. So the West End became part of Hartford in

1637. This newly acquired land was gradually parceled out

by each of the two plantations to its members, or identified as

common land gradually moving westward. However, for some unknown reason an area known

as Bridgefield (most of the current West End) was identified

well before areas to the east of it, at some point between

Hartford's founding and 1651 during the first town clerk's

appointment. It was not part of a

plantation division, which was generally based on a formula. Nine of the

50 original settlers: Haynes, Hooker, Goodwin, John Allyn,

Talcott, Wadsworth, Goodman and Lewis shared land in Bridgefield.

Bridgefield was a rectangle that stretched west from the

current Park River for six tenths of a mile, a few blocks

past what is now the Hartford city line at Prospect

Avenue. It stretched north and south from what is now Capital

Avenue to about Elizabeth Street on the north. The current Farmington Avenue

ran down the middle. In 1697 divisions were made here for

the nine owners. On average each

would have received parcels over 30 acres. Since each

would also have received large amounts of land for grazing when

they settled in 1636, presumably the West End remained wooded

for quite some time.

Typically land would start out as wooded, then

would be cleared for grazing land, and eventually improved as

farm land. A large 'country' home might be built, or

perhaps the farmland could be sold off in large parcels and

subdivided into building lots which were typically 1/4 to 1/3 of

an acre. Over 350 years, this was also the progression of

development in the West End.

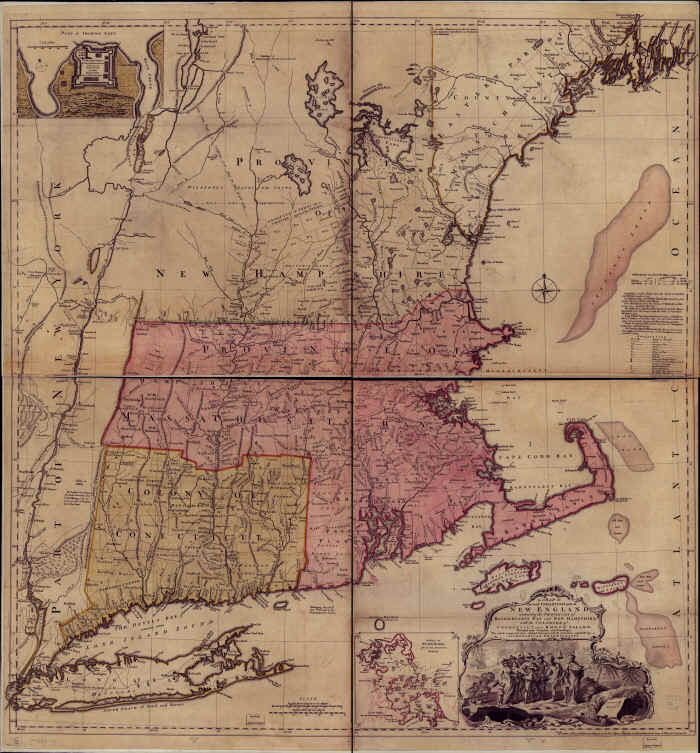

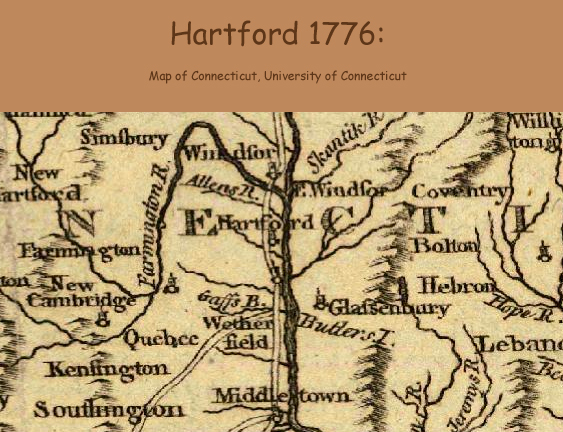

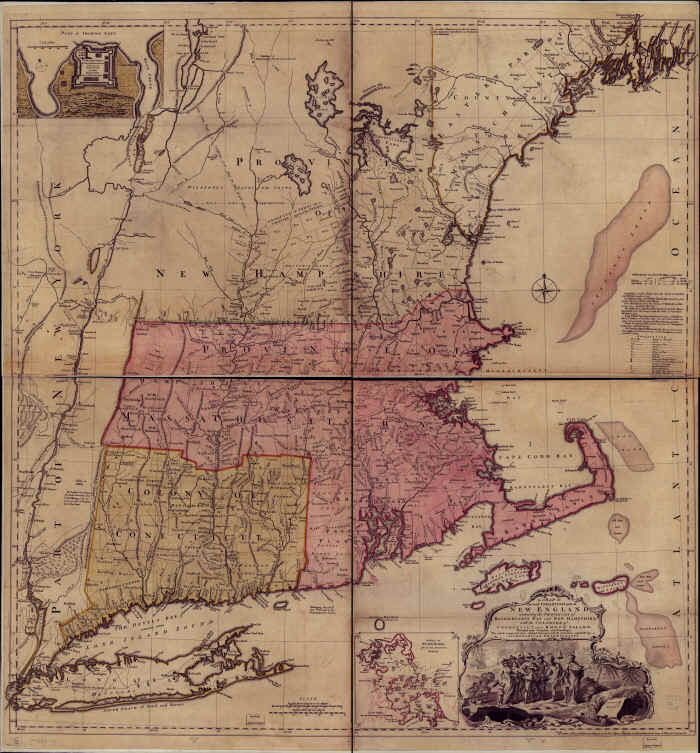

1755-1766:

Hartford's Pre-Revolutionary

Period:

In pre-revolutionary CT, Hartford is the crossing point for the

Post Road going up the east

and west side of the

CT River into Massachusetts, through Springfield to Boston and south

through New Haven, then west to Danbury and south to New York.

The shoreline post road goes to Providence, R.I.

These historic post roads mirror present-day I-91 inland and

I-95 along the shore.

Below are the Thomas Jefferies map of the northeast, 1755,

and the

Miles Park map executed for the Earl of Shelborne, His Majesty's Secretary of

State -

"The Colony of Connecticut, North America, 1766".

Click maps for enlargement

.

The original footprint for Hartford included

present-day West

Hartford, East Hartford and Manchester.

East Hartford will split off in 1783, including Manchester, which

will incorporate in 1823.

West Hartford is part of Hartford for the first 215 years, until

1854.

The meeting house and two churches are shown in Hartford:

currently Center Church and South Congregational churches.

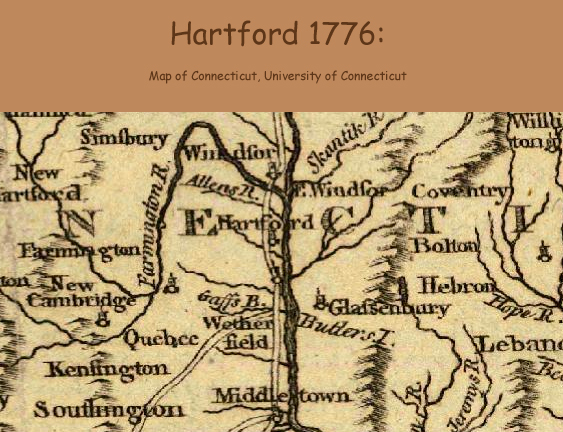

1776-1796:

Hartford's Revolutionary Period

By 1776, the beginning of the Revolution, the

major roads in the state appear much as they did twenty years

earlier.

A map dated 1780 shows

Farmington Avenue extending from Hartford all the way to

Fairfield.

The current cities of West Hartford, East Hartford and Manchester are still part of

Hartford.

Bohn's 1796 map shows the Wells Ferry crossing at

Hartford. In addition to the town center, there are four grist mills, 2 saw mills, an oil mill and a paper

mill in Hartford.

Four roads fan out from Hartford (Albany, Asylum,

Farmington and New Britain avenues).

1811:

Hartford During the British Embargo

By 1811, the developed core city has spread

a couple of blocks in each direction. Major homes are along

Washington Street and Maple Avenue. The Warren map shows only three grist mills in the city, a

reduction in small manufacturing within the city limits, compared to 15 years

before.

This is a period of British embargo spurring small manufacturing

everywhere throughout New England. But Hartford has

developed as a major shipping port - the most northerly navigable

point in the CT River.

Now eight major roads form the routes to towns outside of the City

of Hartford.

The first bridge across the CT River at Hartford was built the

year before, in 1810. It was an uncovered bridge made of

wood. It will be washed away in the flooding of 1818, and

replaced with a covered bridge.

Click map for enlargement.

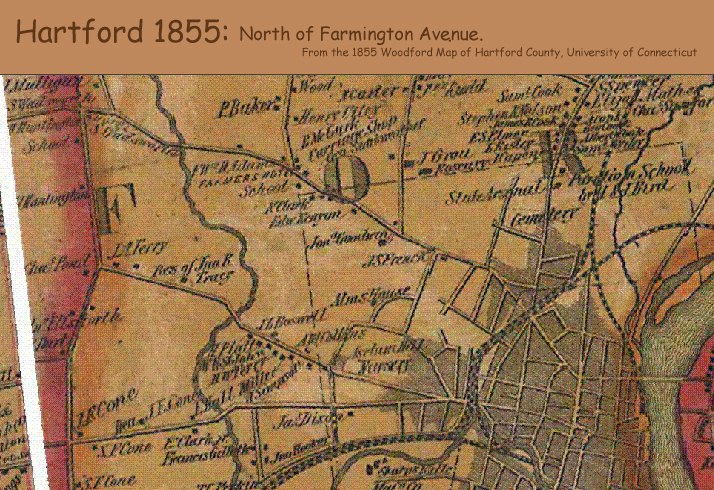

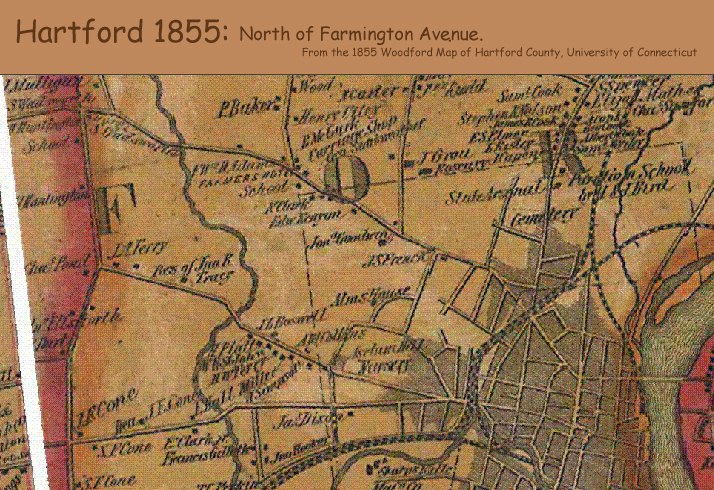

1855:

Hartford in the Industrial

Revolution

Samuel Colt

gets his own factory in 1847 on Pearl Street. He is 32,

finally able to control his own product patented 11 years

earlier. Colt's manufacturing genius was to perfect the

concept of interchangeable parts - 80% of his gun was made by

machine alone. He hired Elisha Root as head superintendent

from the Collinsville Axe Co. By 1855 Colt builds his

spectacular armory along the Connecticut River, designed and

constructed by Root who would go on to train a generation of

engineers including Pratt and Whitney.

The railroad from Hartford to New Haven (1839),

skirts downtown and connects with a spur

to steamship service from the Hartford dock to New York.

There has been rail service to Boston for 9 years and to New York

for seven.

The path of the railway will define the highway footprint

constructed 100 years later.

The

West End in 1855:

By now, urban development has spread west

out to Flower Street, on the eastern edge of what is now Aetna.

The year before, West Hartford split off and

incorporated as a separate town, making Hartford's west boundary Prospect Avenue.

There are thirteen homes located in what is now the West End, all

of them along the only streets: Albany, Bloomfield, Farmington,

Asylum and Prospect - all

major routes from the city to other towns. The rest of the

land is primarily flat farmland divided by whitewashed wooden

fences.

1869:

Hartford after

the Civil War

Fifteen years later, the city has expanded west

into the current Asylum Hill neighborhood. It is 4 years

after the Civil War, and Hartford is still a major port city -

with 22 piers. Bushnell Park has just been built.

Harriett Beecher Stowe, world famous author of Uncle Tom's

Cabin (1851), moves to "Nook Farm" in Hartford

in1873. Mark Twain builds his house next door to her in 1874, and

publishes Tom Sawyer two years later.

The West End in

1869:

Fourteen years later, there are only 10 more houses in the West End - now totaling

23, and one more street has been added in the neighborhood - Sisson

Avenue. The area, then known as "Middle District', is still mostly

farmland.

Next year, Eugene Kenyon will build a path north of his home on

Farmington Avenue and build his farm house halfway up what is now

the first block of Kenyon Street (now 96 Kenyon).

It will be the first home in the neighborhood built off of one of

the major avenues.

Click map for enlargement, or click for pdf

file.

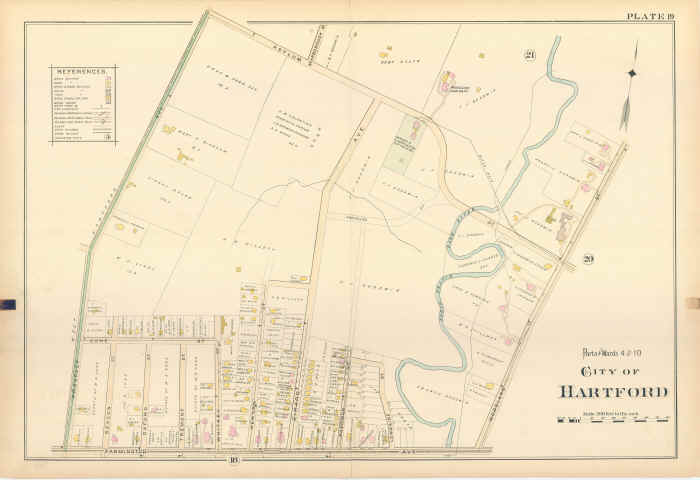

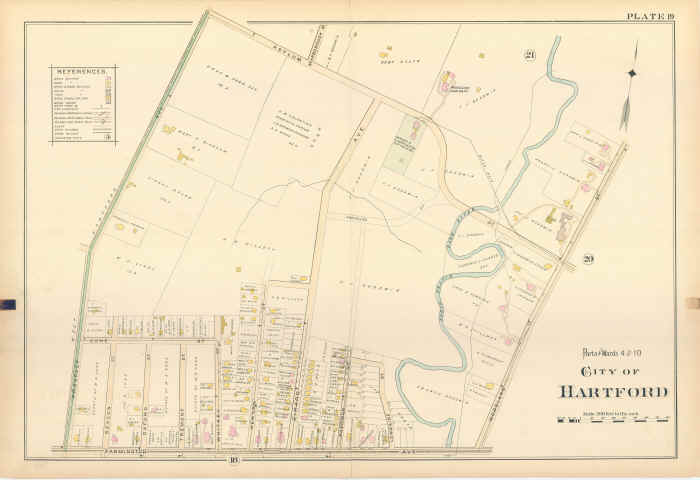

1896:

Hartford's Gilded Age

The covered bridge across the

Connecticut River burned the year before in 1895. The current Bulkeley Bridge is a stone arch bridge that opened

thirteen years later in

1908. It is one of the oldest bridges in use by the interstate

highway system (I-84).

The

West End in 1896:

xxx

Click map for enlargement, or click for pdf

file.

1909:

Hartford is fully urbanized

Hartford

The

West End in 1896:

xxx

Click map for enlargement, or click for pdf

file.

Many thanks to the Hartford

Preservation Alliance for the loan of the last three original

city plates from 1869-1909.

Maps digitized by C. West Designs.

The 1636 map most of the 1636 content appears in The

Colonial History of Hartford, William DeLoss Love, 1914.

Thanks to the University of Connecticut for the early maps of

Connecticut: 1766-1855.

|