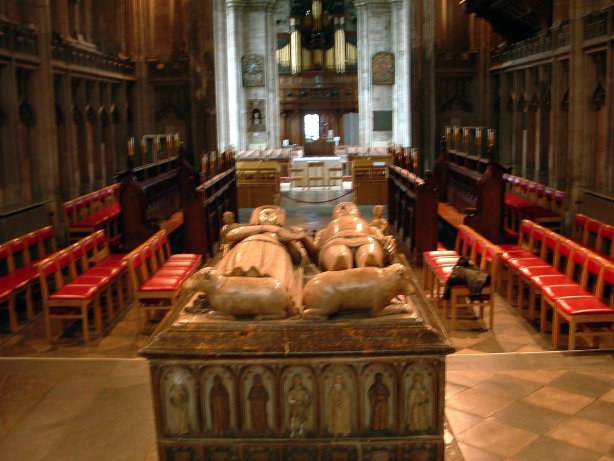

The tomb of Katherine and Thomas Beauchamp in St. Mary’s Church, Warwick, England. From the church-provided plaque: “Thomas Beauchamp (1313-1369). Earl of Warwick. Knight of the Garter. Lord Marshal of England. Guardian of Edward, Prince of Wales (The Black Prince). Commander at the Battle of Crecy (1346). Katherine. Countess of Warwick. Daughter of Roger Mortimer, Earl of March.”

(As a side note, while that may look like a French name, and you may think to pronounce it bow-shamp, we were quite assured by the English lady at the church that it was pronounced bee-chum. Don’t ask me how they came up with. Of course, it’s not War-wick, it’s Warick.)

Unfortunately, it is impossible to know the exact date this tomb; if the church had a record of when it was completed and installed, that information wasn’t on display. If Katherine had died prematurely (as she was almost certainly younger than Thomas), he would have almost certainly gone ahead and commissioned the tomb for her with his likeness on it as well—meaning it would have been almost certainly have completed before his death in 1369. If, however, he died first, and had not had work begun on it before his death (as was common) it might not have been completed until a few years after his death. I think we can say on this tomb, that it predates 1373 (their clothing confirms this as well). If Thomas was 20 when he got married (highly unlikely, but it’s a nice round number), then it couldn’t have been started before that time, making the front-end date for the tomb 1333, although more likely 1343.

We will begin by looking at Katherine, and, to a lesser extent (because he’s almost entirely clothed in armor, not fabric), Thomas. Katherine is wearing a simple, lace-front cotehardie. Her sleeves are long and come down partially over her hand (what is often referred to as a “mitten sleeve”. They button-up slightly past her flexed elbow (see picture below). Her lacing begins below her hip belt (about the span of a woman’s hand below the belt. If you look closely at the beginning of her lacing, the second set of eyelets are not parallel to one another, as the first set are; one eyelet is half again as far from the first eyelet as its mate is. This was undoubtedly done to facilitate the spiral lacing; when the eyelets are parallel to one another, you get a slight puckering at the bottom and a slight unevenness at the neckline (not that any of my lace-up cotehardies produce this puckering, of which I am knowledgeable. Ahem.). Aside from the buttons on her dress, Katherine’s cotehardie is very plain, lacking any indication of embroidery or brocaded pattern. I think we can be assured that it was all one color and patternless (I’ll share with you why I think that further below).

We will start at Katherine’s head and work our way down. I have oriented her so that you see her veil as it would have appeared when she was standing up. The thing about tomb effigies is that they were, from a clothing standpoint, carved as if the figures were standing upright; all of the belts, veils, folds of clothing, etc., hang as if they were on a person standing upright, not lying down. Of course, everyone--not to mention clothing-- looks better standing up than lying down, which is my thought on why they did it that way.

The very first thing that you may notice is Katherine’s veil. In all ways but one, it mimics the ruffled-edge or “nebula” veil so popular during (and even after) Katherine’s lifetime. The main different between those veils and hers, however, is that Katherine’s veil clearly is not ruffled. I don’t think anyone could confuse the X’s in her veil with ruffles. So what are the X’s? After a great deal of study, and racking my brain as to what can cause X’s in fabric, I believe that I have come up with an answer: smocking. I believe that Katherine’s veil was smocked down the length of its center, folded in half, stuffed with a roll of wool or cotton, sewed together just behind the smocking, and then placed on top of the wire-frame headband that I discussed on the “Shoes, Etc.” page. I have done a bit of smocking and am convinced that Katherine’s veil is indeed smocking. As I am having to teach myself smocking as I go, I haven’t made a lot of progress so far towards actually recreating her veil in its entirety, but I think I have the hang of it now, and I see some changes that I need to make in terms of the amount of fabric I need, the scale of the smocking, and the firmness of the fabric. More to follow.

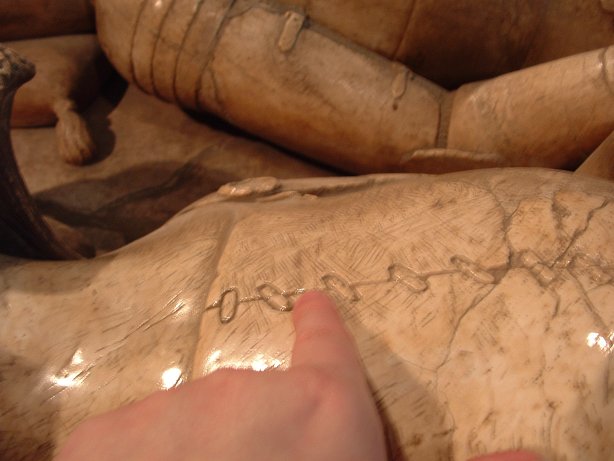

Here we have two pictures of the front of Katherine’s top. At the top, we see that Katherine has a very square neckline. At the bottom, we can see from my finger that her lacing is spaced about an index-finger’s width apart. Note that, at the top, the eyelets are again placed parallel to each other and the final (or beginning) “stitch” is straight, not angled.

A slightly better angle on Katherine’s mitten sleeve. Notice the very obvious curve to it.

Here you can see the buttons as they go up past her elbow.

Here is a picture of Katherine’s sleeve buttons with my finger for scale. They are about the size of a woman’s pinkie fingernail and are set to that two buttons almost fit in the width of my index finger. As I discussed before on the “Fabric” page, I believe that a nickel would be about the correct size for a template to make these buttons from cloth. Of course, there is no evidence that these buttons were of cloth, but we do know that cloth buttons were very popular. However, a woman of Katherine’s rank and wealth could have worn metal or other types of buttons if she so chose.

Also note that she does definitely have buttonholes. I have been wondering for some time if some sleeves didn’t have false buttons on them—that is, buttons which were sewn onto a closed sleeve and which were never made functional by the addition of a buttonhole. While that may have still have been done in some cases, clearly Katherine’s buttons are functional. What has to be remembered about the middle ages is that their economy was backwards to our own: materials were expensive but labor was dirt cheap. While we may wonder at the time spent putting so many buttons and buttonholes on a dress, for Katherine, that was the cheapest part of the operation. If she did indeed have metal buttons, they would have certainly cost more to purchase than the cost of the labor the seamstress or tailor who sewed them on.

A different angle of Katherine’s belt and lacing.

A better shot of Katherine’s belt buckle. I believe the flowers on her belt to be metal plaques. While we know that people had woven belts with fanciful designs, these flowers have been carved in relief, indicating that they stand up higher than the belt itself, and are, therefore, unlikely to be woven or embroidered designs. As metal-decorate belts were very common among men, I can only assume that this belt is a woman’s version of that same belt. I would estimate that her plaques were placed about an index-finger’s width apart, maybe a little less. But note where her belt buckles that there is, in the uniform spacing of things, one plaque missing so that the belt can buckle properly; however, aside from the one missing plaque, the rest of the belt is decorated in the same spacing manner as previously. Also note that this is clearly a tongued belt, unlike the single-loop buckled belts which are so popular in the SCA.

After examining this picture for some time at a high rate of zoom, I have decided that Katherine has a double-loop belt catcher. I think it is a metal plate attached somehow attached (perhaps through one of the rivets that also holds on a decorative flower plaque) to the back of the belt, with two loops at either end which wrap around the belt. The excess belt is then run through these two loops, as you would run your watch strap through two loops, and then left to hang. If you look closely at one flower on Katherine’s belt, you will see a straight line which runs over it and down to the bottom layer of belt. I believe this is the first belt-catcher loop. The second loop has been broken off, but it would logically be placed right next to where the belt turns to fall down (under high zoom, you can see a mark in the belt where something used to be).

Now we come to Thomas, whose only visible cloth apparel is his heraldic surcoat. And here is the reason why I think that Katherine’s dress was plain; if the artist went to the trouble to show Thomas’s fabric decoration, why not show Katherine’s (if it existed) as well? Some may argue that the carver was suddenly overcome with a fit of laziness, or her fabric pattern wasn’t as important as his heraldic pattern, but I find both theories hard to swallow in light of the carver carving each and every link in Thomas’s maile so very clearly. The carver wasn’t a man (or woman) to be distracted from important points. Given that brocade and embroidery are both signs of wealth, it looks like if Katherine had had either on her dress, it would have been displayed.

Speaking of Thomas’s decoration, I believe that these crosses have been either appliquéd or embroidered onto his surcoat, as they, like Katherine’s belt plaques, are clearly raised. Had they been painted onto his coat originally, they could have been shown via a shallow outline carved down into the stone, rather than using the more difficult technique of carving the material around them away. It is impossible to tell if these were appliquéd or embroidered, as we can’t assume that the carver would have bothered trying to show embroidery stitch-lines, if they had existed (he did not show the seams in Katherine’s dress). But I have appliquéd a nearly identical cross onto two of my husband’s surcoats (one in fabric, which had to be hemmed as it was sewn down, one in felt which did not need to be hemmed), and can definitely say that appliqué in this case is both possible and fast (at least faster than, say, couching embroidery).

You might notice that I have been working under the assumption that the tomb effigies are carved to the likeness of Katherine and Thomas, and to the likeness of their clothing. Katherine and Thomas were extremely important people, and, given that they built St. Mary’s Church, extremely wealthy. The likelihood that they used some sort of pre-carved tomb effigy or “off the rack” effigy design is unlikely. The whole point of a tomb effigy is to be remembered so that people will pray for your soul to be released from purgatory. It might be a bit dicey having a tomb effigy that looks like someone else; when someone looks at your effigy and prays for you, are their prayers going to reach you or the person whom the image, which they have in their minds, most resembles?

In addition to that, we found at Westminster Abbey that there was actually a movement, beginning in this period, of literal likenesses in tomb effigies. I can’t remember if it was King Edward II (who was Thomas’s king), or the king who came immediately before or after him, whose effigy was carved based on his death mask. Queen Elizabeth’s effigy was also made from her death mask, as where some others in between the two in time. So there was something of a drive to have as accurate a representation on the tomb as possible. While not everyone’s effigy was made from their death mask, that does not mean that it was not carved earlier in life, based on a somewhat younger face, or carved from a sketch or painting of the person. While the clothing that was worn may or may not have been personally owned by the person depicted, both Stuart and I have agreed that Katherine and Thomas’s clothing and armor are quite typical of their time period, based on other images. So, even if they never actually owned outfits such as they are wearing, I think it is safe to say that what they were clothed in what was standard for the day, and can therefore be relied upon as being accurate for the study of 14th century clothing and armor.

Well, ladies and gentlemen, we now enter the most exciting, unusual, and highly speculative part of our look at 14th century costuming. We now move down to the weepers along the bottom of Katherine and Thomas’s tomb. The first thing we must wonder is: do these represent real people? Before going to England, I would probably have said “most likely not”. However, Westminster Abbey changed my mind. When Stuart and I had a look at the backside of Edward III’s tomb, I was excited to see a couple of female representations that I had seen in various sketches (in fact, one had on the sideless surcoat on which I modeled my own for my wedding). When Stuart took a closer look at the effigy, however, he said, with some surprise, “These are his children!” He then pointed out the small coats of arms under a couple of the male figures, identifying one as Edward, the Black Prince, and one as his brother. He recognized one of the women’s arms too, although he couldn’t remember which daughter she was. We do not know how widely known this fact is; when we mentioned it to the rector nearby (when we were trying to figure out who another knight was), he was rather surprised to learn that the weepers represented Edward III’s children. King Edward had more children than he had weepers on his tomb (at least on the backside; although I don’t recall seeing any on the front side), so Stuart thinks that it may be his favorite on the tomb. The Black Prince proceeded his father in death, but the brother next to him didn’t, so we can’t find any other better explanation for the selection of just some of his children.

So, we are back to the question of whether or not the weepers on Katherine and Thomas’s tomb represent real people. There are certainly too many of them to represent their children, and some are clearly older men; men as old or older than Thomas when he died. They may be relatives, or friends, or a combination of both. Do they represent real people at the funeral, or, like Edward’s tomb, are they a combination of the living and the previously deceased? I am afraid that we will never have an answer to this question. But, as you look at these figures, I think you will notice, as I have, that each is very different in likeness; if they don’t represent real people, the artist certainly reached into the depths of his creativity to come up with a variety of faces and garments in order to make each and every weeper unique.

Speaking of garments, there are many items represented here that I have either never seen before, or that I have never seen in this century. While scratching my head over some of the bizarre items worn by some of the women, Stuart said something about the men in their heavy cloaks, which explained all of the weepers’ dress, including the bizarre female garments: they are all attired in their winter wear. Why the carver chose to have all of the weepers in winter clothing—did Katherine or Thomas die in the winter?—is, and will remain, a mystery.

I’m going to be a tease and start with the men because their dress is not nearly as exciting as the women’s, although, I must admit, they have an exciting and unexplained detail or two between them.

Figure MJ1. Compared to the rest of the men featured on the tomb, this man is one of the younger ones. After studying a number of pictures from this time period, I have come to notice a few traits which are common with youth and some that are common with advanced age. Younger men wore short beards and/or moustaches at this time, while older men tended to have longer beards. Older men also tended to wear their hair longer. And lastly, and most telling, cotehardies, especially very short ones, were almost exclusively the prerogative of young (and shapely) men. So, based on the short hair and the short cotehardie, I believe this to be a younger man (it is hard to tell in this picture how long his beard is, but I figure we have two out of three, so the beard isn’t that important one way or the other).

Our figure is wearing a rather small hat, which appears to have a rolled brim of some sort. These were apparently quite common, as we see a number of the figures wearing them. Most unusually, he is wearing his sword at his front. I am not sure of the purpose of this, as it would seem to make walking more painful (ever had a sword beat against your shins for a while?). We can just see the hem of his cotehardie below his hip belt and it appears to have some sort of small dagging around the edge, or else some sort of trim with a scalloped edge.

If you look closely at his arms, you will see an indentation about halfway up the forearm. It would appear that his sleeves are only about 3/4 in length, and that he is showing his under-cotehardie sleeves the rest of the way down his arm. There is also an odd line slightly above his waist and bisecting the cotehardie horizontally. If this is a seam line, I have never seen its like on a cotehardie before. It does, however, mimic the same line on Thomas’s figure. At first I thought this line was indicative of the coat of plates he was wearing under his surcoat, but my husband has since pointed out that he thinks it is part of his heraldic arms, and upon re-inspection of the picture, I have to agree that it does appear to be a stripe of fabric, rather than an indication of armor (the stripe also matches his arms, as displayed on the information plaque). We know from many accounts that a knight’s retinue (his squires, men-at-arms, and even household servants) would have worn his arms or a variation of his arms during certain ceremonies and in public at certain times. Perhaps this gentleman is one of Thomas’s men and we are seeing the striped part of Thomas’s arms on his garment.

However, we cannot, at this time, positively rule out that he is wearing some armor. It is highly unusual, for instance, that he does not have a center seam up the front of his cotehardie to button or lace it closed. This would make this the first instance that I have ever seen of a man’s cotehardie which did not open up the front. However, surcoats, like Thomas’s usually lace up the sides (Thomas’s does). So, we could have here a heraldic surcoat, such as would have been worn over armor. That doesn’t mean that it was being worn over armor at this time, but if we look at the smooth, tight fit of Thomas’s surcoat, I think we can assume that this surcoat, if actually constructed to be worn over armor, would not fit so nicely when worn without the layer of armor beneath. I think, if this is a surcoat, it is being worn over armor.

I have to admit that I have never seen an image of a heraldic man’s cotehardie, although, based on numerous general descriptions of liveries that I’ve read, they probably did exist. An opening down the front of the cotehardie would spoil, to some degree, the arms, so they may have constructed heraldic cotehardies differently—giving them a back, or, more likely, side openings. The only potential flaw with that thought, however, is that women’s heraldic cotehardies (which I have seen evidence of) did still have the front-opening. Although it must be pointed out that they were always wearing their arms split with their husband’s arms, so the front opening lay on the natural division of the two, and so ruined neither.

And finally, to return to the armor theory, if we assume that this man is wearing armor, it would explain the rather unusual dagging around the bottom of his garment: a maile shirt peeping out from under the hem would create such a look.

The next problem with the it’s-not-a-cotehardie-it’s-armor theory is that he is clearly not wearing any leg armor, and doesn’t appear to be wearing any arm armor either (although it’s hard to tell around that one flexed elbow—what I might be seeing as a short over sleeve may be a long elbow cop on top of his maile or cloth undershirt). In fact, he appears to be wearing hosen with attached feet (the kind which had leather soles and were used in place of separate shoes). So, we either have a very different kind of cotehardie—one that doesn’t open up the front and has unusually small dagging or some sort of dangling trim around the bottom—or we have a man walking around wearing his body armor, maile shirt, and surcoat, but none of the rest of his armor (although, you have to admit, it’s a lot easier to walk around in armor if you have nothing on but the body armor).

Figure MM1. Here we have our second figure in cotehardie-like attire, although we can say with certainty that he is definitely wearing a cotehardie. He too is a young man with a short cotehardie, short hair, and either a short beard or none at all (hard to tell if that’s beard shading or a bit of dirt on the tomb). Here were have that small hat again.

His sleeves are long and appear to be a mitten cuff like Katherine’s, which I have not previously seen on a man’s cotehardie. It’s hard to tell, but he may have buttons running up his left arm (see the white mark on the edge?). He is also wearing a rather large hip belt, which comes all the way down to the hem of his cotehardie. Both Stuart and I have discussed the fact that there was no way that a man could wear a belt so low naturally (much less one so heavy with metalwork), and so it either has to be sewn directly onto the cotehardie, or there has to be belt loops somewhere. I am leaning towards sewing the belt on as I have never seen anything resembling a belt loop depicted in any picture or three-dimensional figure.

It is impossible to say with certainty whether or not he is wearing shoes, but I think that he, like the other figure, may be wearing the soled hosen. There is an odd line at his waist, that would almost indicate a waist seam, except we are back to the fact that I have never seen a horizontal seam on a man’s cotehardie; I think, instead, that this is perhaps a slight wrinkle in the fabric. I have seen pictures of cotehardies on women which were so tight, there were wrinkles in the material. He is also standing so that his weight is slightly shifted to one side, which could also cause a slight wrinkle.

Figure MP1. Here we have our last cotehardie figure. It is hard to tell with him whether he has the same, rolled-brim hat on, or if he’s wearing a rather thick circlet. The tops of the other figures’ heads are smooth and hat-like, while this figure’s head could go either way, given some of the lines caused by damage to him.

He is, perhaps, a bit older than the other two men, as his beard and hair are a bit longer. Also, there is something in his face that looks a bit more aged. His cotehardie almost certainly has some sort of pattern to it. What is not obvious, however, is whether his sleeves are patterned. The one white sleeve appears to be patterned, but this is a repair job and so can’t be trusted, especially given that the pattern doesn’t seem to appear on the other sleeve. Note the buttons which are so small as to barely be visible (in contrast to the previous figure).

What is very odd is that it appears that his hip belt is above his crotch, although I have never known a cotehardie to be that short. Given that most of the figures stand with their arms crossed in front of them at their waist, it would seem that the hip belt is low enough to cover the crotch. I think that this is probably the case, but the damage to his legs makes them appear to come together at his groin where they really don’t.

Figure MF1. Here (and following) we have the two strangest figures on the tomb. At first glance, I took these figures to be old women, until I noticed they had swords. Unless I am very much mistaken, at this period in time, swords were highly regulated and the exclusive prerogative of knights and other lords, or their personal retinue (i.e. squires and men-at-arms). So who are these men, and what are they wearing? You will see from pictures further below that these garments do not match the long robes which are common of older men and men of public stature (e.g. city officials). This garment is large, lumpy and, frankly, shapeless. Even the old men’s robes are less bulky than this garment. And what’s that on his head? The fact that he appears to be wearing a wimple or barbette is what make me originally think that he was an old woman.

A lot of questions and few theories out of me on these two. The only thing I can think of to explain the hood is that it is a maile coif with a skull cap on it (or else one of those mysterious caps that everyone else is wearing). It may be that the garment is bulky because it is covering a man dressed out in full armor. Perhaps this is a coat that he is wearing over his armor? I will show you later some women who are wearing coats which are very clearly lined in a heavy fur; if he is also wearing a fur-lined garment, that might explain the bulk.

One last feature of interest to note: he has full-fingered gloves in his hands. By the way he is holding them, they are not metal gauntlets but leather or cloth. Also note that the sleeve of his right arm is either much shorter than the left sleeve, for some reason or is rolled up. If it were not for the sword, I would have pegged this man, not only as a woman, but as a laborer. I have to admit, that while I wrote a paper on death and dying in the middle ages back in college, I can’t remember if family members and/or friends served as any sort of pall bearers. The odd clothing of both men, along with their gloves, seems to set them apart from all the other weepers. They may have been involved in the funeral somehow, and their clothing specific to mourning/caring for the dead.

Figure MQ1. Here we have the second unusual weeper. Interestingly, he has the exact same pose as the previous weeper, down to the gloves held in his right hand. While all of the other weepers have adopted poses that are fairly standard for medieval people at this time, these two have poses that are not standard; they almost seem to be prayerful, or attempting to convey sorrow.

Next we move on to our line of older, robed and cloaked men.

Figure MG1. This is our most interesting older gentleman. Here we, again, have that rolled-brim hap. Next we have this odd, half-length mantle. It buttons up the front and had a fold-down collar (what we might today refer to as a peter-pan collar). Underneath his half mantle he is wearing a long robe and hip belt with metal plaque decorations. He, like one of the cotehardie figures, is wearing his sword in front of him, rather than to one side. Again, I am unsure as to the reasoning behind this. It is possible that the effect is symbolic, which means it may or may not have come from real life; but it may also simply be that a few men wore their swords in such a manner, even if we don’t know why.

It is interesting that this is the only figure who is standing with his arms behind his back (yes, they are definitely behind him, not accidentally broken off).

Figure ML1. An man with a longish beard. He seems to be wearing a coif, rather than the popular rolled-brim hat. His full-length mantle buttons over his right arm, which was quite common in mantles in this period. One arm is wrapped up in the mantle, but with the other arm we can see some sort of patterned material. It is so bulky compared to other men’s sleeves, that I’m inclined to say that it’s some sort of quilted garment. We know that gambesons and other under-armor garments were quilted; it could be that winter clothing for non-armor use may have also been quilted (I know my husband has worn his gambeson as a coat during cold weather at events). It is interesting that his forearm does not repeat this pattern. It could be that he was wearing some sort of vambrace over his sleeve; if the upper part of the sleeve was indeed quilted, it could be that the lower arm was not; the upper sleeve may only be a ¾ sleeve and we are seeing his undershirt sleeve; or it could be that he has a different material sewn onto the lower part of his sleeve for decoration.

Figure ML1. An man with a longish beard. He seems to be wearing a coif, rather than the popular rolled-brim hat. His full-length mantle buttons over his right arm, which was quite common in mantles in this period. One arm is wrapped up in the mantle, but with the other arm we can see some sort of patterned material. It is so bulky compared to other men’s sleeves, that I’m inclined to say that it’s some sort of quilted garment. We know that gambesons and other under-armor garments were quilted; it could be that winter clothing for non-armor use may have also been quilted (I know my husband has worn his gambeson as a coat during cold weather at events). It is interesting that his forearm does not repeat this pattern. It could be that he was wearing some sort of vambrace over his sleeve; if the upper part of the sleeve was indeed quilted, it could be that the lower arm was not; the upper sleeve may only be a ¾ sleeve and we are seeing his undershirt sleeve; or it could be that he has a different material sewn onto the lower part of his sleeve for decoration.

Due to the length of the mantle, it is actually difficult to ascertain whether or not this figure is wearing a robe underneath. The mantle is pulled up above his ankles on his right side, and I can see no indication of a robe beneath it, but one has to wonder if his robe was pulled up as well, or if it is not quite as long as the others’ robes.

Figure MB2. Back to the hat. And again, we have a man with long hair and beard and an older face to match his older clothing. His mantle buttons up in the front (see the open seam line below his hand?), but has decorative buttons at the right shoulder as well. His mantle does not have the peter-pan collar, although it does seem to have a small band of trim or bias tape-like facing. It also appears to be pleated or gathered over the left shoulder.

Figure MB2. Back to the hat. And again, we have a man with long hair and beard and an older face to match his older clothing. His mantle buttons up in the front (see the open seam line below his hand?), but has decorative buttons at the right shoulder as well. His mantle does not have the peter-pan collar, although it does seem to have a small band of trim or bias tape-like facing. It also appears to be pleated or gathered over the left shoulder.

Figure MC1. The best picture yet of the hat. From this angle it could be a fur hat, where the fur is turned to the inside, while the outside may be left bare leather, or covered in fabric. The fur may be turned up and stitched for decorative edging, or merely flipped up by the wearer (which means that it could be flipped back down to cover more of the head, when necessary). It could also be a Monmouth cap, which was a knitted cap very popular in England during the middle ages (and much later; they were still wearing them in the 18th century). It had a double-thickness band around the bottom which could be worn flipped up. I have made one of these myself, however, because so many hats look alike (they could also be some sort of felt hat with rolled brim), it’s impossible to say how this hat was made.

Figure MC1. The best picture yet of the hat. From this angle it could be a fur hat, where the fur is turned to the inside, while the outside may be left bare leather, or covered in fabric. The fur may be turned up and stitched for decorative edging, or merely flipped up by the wearer (which means that it could be flipped back down to cover more of the head, when necessary). It could also be a Monmouth cap, which was a knitted cap very popular in England during the middle ages (and much later; they were still wearing them in the 18th century). It had a double-thickness band around the bottom which could be worn flipped up. I have made one of these myself, however, because so many hats look alike (they could also be some sort of felt hat with rolled brim), it’s impossible to say how this hat was made.

This is also one of two figures who wears a large flower brooch at the front of his mantle. Since neither arm if visible, we can only assume that the mantle comes together at the front. Whether this brooch is merely decorative, or whether it holds his mantle together is debatable. If you look closely at his neckline, it appears that he has either a small collar or a trim/bias tape neckline.

Figure MK1. This is the other figure with a flower brooch. He too has a front-opening mantle, although it appears that he has no decorative collar or edging around the neckline of his mantle. He does, however, have dots (carved down into the stone, not in relief) along the bottom of his mantle. These could indicate some sort of embroidery, or maybe even sewn-on jewels. It is odd, however, that the dots would be carved into the stone if they were supposed to indicate embroidery or jewels, both of which, like the flower brooch, should have been carved to stand up above the fabric of the mantle. These may, therefore, indicate some sort of decorative eyelet.

Figure MK1. This is the other figure with a flower brooch. He too has a front-opening mantle, although it appears that he has no decorative collar or edging around the neckline of his mantle. He does, however, have dots (carved down into the stone, not in relief) along the bottom of his mantle. These could indicate some sort of embroidery, or maybe even sewn-on jewels. It is odd, however, that the dots would be carved into the stone if they were supposed to indicate embroidery or jewels, both of which, like the flower brooch, should have been carved to stand up above the fabric of the mantle. These may, therefore, indicate some sort of decorative eyelet.

Figure MD1. This figure is wearing a mantle which is neither front-opening or side-opening, but rather is somewhere in between. We can see by the points of his collar that this mantle is not merely one or the other styles which has merely become crooked. He is also wearing a hood, which is not separate. It has been expressed to me that, at this point in the middle ages, people did not have (at least as far as anyone can tell) a hood which was attached to a cloak. Well, here it is. I will admit, however, that it is impossible to tell if the hood is attached to his mantle or if it’s a hood that goes with his robe beneath and the mantle has just been pulled on over it, but while I have seen separate hoods with cotehardies before, I have not seen a separate hood worn with a robe. I think this really may be a case of an attached hood.

Figure MD1. This figure is wearing a mantle which is neither front-opening or side-opening, but rather is somewhere in between. We can see by the points of his collar that this mantle is not merely one or the other styles which has merely become crooked. He is also wearing a hood, which is not separate. It has been expressed to me that, at this point in the middle ages, people did not have (at least as far as anyone can tell) a hood which was attached to a cloak. Well, here it is. I will admit, however, that it is impossible to tell if the hood is attached to his mantle or if it’s a hood that goes with his robe beneath and the mantle has just been pulled on over it, but while I have seen separate hoods with cotehardies before, I have not seen a separate hood worn with a robe. I think this really may be a case of an attached hood.

The figure also appears to have some sort of patterned sleeves, as well as having trim at his cuffs.

Figure ME1. You can’t tell me this isn’t an old man; compare his stooped shoulders with the rest of the men’s postures.

Figure ME1. You can’t tell me this isn’t an old man; compare his stooped shoulders with the rest of the men’s postures.

He has a mantle which opens over his right shoulder. There is some sort of decorative element there; I think it was originally a circle, and just part of it has been broken off. Most likely it represents a brooch of some sort. His mantle neckline is a bit wider and rounder than those on the other men’s mantles, but does have some sort of trim around it. The left side of his mantle is bunched up oddly, but I think this is because he is doing something with his left arm. From that, and the way he is standing, I almost except to see a cane protruding from his mantle, but if there was ever one in existence, it is no longer there.

Figure MH2. A fairly non-descript figure, wearing a combination of styles which we have seen before on other figures. However, note that not only is he wearing a hood, but that it, like the other one before it, appears to be attached to his mantle.

Figure MH2. A fairly non-descript figure, wearing a combination of styles which we have seen before on other figures. However, note that not only is he wearing a hood, but that it, like the other one before it, appears to be attached to his mantle.

Figure MI1. A fully-cloaked figure. It is hard to tell with him, however, whether he is wearing a closely-fitting hood or a slightly loose coif. Again, there is no tell-tale hood-mantle over his regular mantle to indicate that his headgear is a separate piece. There is a band around his chin which would seam to indicate a short, but stand-up collar around his mantle.

Figure MI1. A fully-cloaked figure. It is hard to tell with him, however, whether he is wearing a closely-fitting hood or a slightly loose coif. Again, there is no tell-tale hood-mantle over his regular mantle to indicate that his headgear is a separate piece. There is a band around his chin which would seam to indicate a short, but stand-up collar around his mantle.

Figure MN1. Yet another very aged man; note the wrinkle lines across his forehead. He also has what appears to be a forked beard. He also is wearing a hood without any indication that it is separate.

Figure MN1. Yet another very aged man; note the wrinkle lines across his forehead. He also has what appears to be a forked beard. He also is wearing a hood without any indication that it is separate.

Figure MO1. Unfortunately this was a bad picture (even worse than usual). We can’t see much about this man other than a repeat of the side-closing mantle, attached hood, and long, forked beard.

Figure MO1. Unfortunately this was a bad picture (even worse than usual). We can’t see much about this man other than a repeat of the side-closing mantle, attached hood, and long, forked beard.

Figure MR1. Another side-closing mantle, another rolled-brim hat. Unfortunately this figure is missing most of his right arm, which means we can’t see if he had a patterned sleeve.

Figure MR1. Another side-closing mantle, another rolled-brim hat. Unfortunately this figure is missing most of his right arm, which means we can’t see if he had a patterned sleeve.

If you noticed, there were 3 young men to 12 old men (plus the two figures in odd robes, holding gloves; I’m not sure who they are supposed to be). Why so many old men, you may wonder? It is my belief that these weepers do indeed represent real people—people who were known to Katherine and Thomas in their lifetimes. Thomas was 56 when he died. If we work on the assumption that medieval people tended to have friends their own age, just as we do today, then it seems only reasonable that Thomas’s friends and contemporaries would have all been older men as well; thus the larger number of old men on this tomb. The few younger men could represent children, foster-children, nephews, or squires (we know that Thomas definitely had family, as there was another Beauchamp laid to rest in the same church). Neither of the figures in the odd robes (MF1 & MQ1) have beards, so I think that they may have also been younger people as well, although, with the odd robes and gloves, it may very well be that they represent professional mourners or some other, wholly unrelated group of people, so I don’t think that we can assume that, if the weepers represent real people, that these two would have necessarily been part of Thomas’s household, or even known to him.

Let’s start our jaunt through women’s clothing with fairly typical clothing and work our way up to the wild stuff, shall we?

Figure WB2. Here we have a fairly nondescript woman with a button-front cotehardie and a mantle. She appears to be holding a book (which is tilted outwards for the observer to view). I’d bet dollars to doughnuts that this is supposed to either a book of Psalms, or a book of Hours, as they were the two absolute most popular books to be personally owned, and this being a tomb, much more appropriate than, say, a book of courtly love poetry.

Figure WB2. Here we have a fairly nondescript woman with a button-front cotehardie and a mantle. She appears to be holding a book (which is tilted outwards for the observer to view). I’d bet dollars to doughnuts that this is supposed to either a book of Psalms, or a book of Hours, as they were the two absolute most popular books to be personally owned, and this being a tomb, much more appropriate than, say, a book of courtly love poetry.

Anyways, conjectures on the book aside, the only thing to note about this figure is her veil. While you may dismiss her veil as being a ruffled-edge, or “nebula” veil, I don’t think that it is. Yes, it is a ruffled veil, but it’s ruffled, in my opinion, the way an Elizabethan collar is ruffled. Nebula veils have small, wavy ruffles which don’t have a lot of volume. They are created by weaving the veil with the warp threads on the selvedges loose, so that the material ripples instead of laying flat. This veil, however, has a lot of height/volume for such a technique; the ruffles are large, clearly visible loops. I think that this veil was constructed as Elizabethan collars were constructed, by starching the daylights out of it and then shaping it over a hot metal rod (the medieval equivalent of the curling iron). Further on I will show you a veil that is clearly a nebula veil, along with veils even more large and voluminous than this one.

Figure WE1. Hey, speak of the devil: here’s one of the even taller veils that I mentioned. See how large and blatantly obvious the ruffles are?

Figure WE1. Hey, speak of the devil: here’s one of the even taller veils that I mentioned. See how large and blatantly obvious the ruffles are?

This figure’s cotehardie is obscured, but I would like to point out that she, like a number of the men, has a peter-pan-like collar on her mantle. Her mantle also seems to be gathered into the neckline, underneath the collar.

Figure WG2. Here we have a nebula veil. See how it has thin, wavy edges? Any costuming book which touches on this period in time will identify this image as that of a nebula veil; it’s identification is not in doubt. But see how it is very different from the previous two veils? They are clearly not meant to represent the same thing. While multiple carvers almost certainly worked on this tomb, it was also most certainly constructed under the care of one master, so there is no justifiable reason for any stylistic anomalies, except that they are accurately reflecting different types of veils worn at that time.

Figure WG2. Here we have a nebula veil. See how it has thin, wavy edges? Any costuming book which touches on this period in time will identify this image as that of a nebula veil; it’s identification is not in doubt. But see how it is very different from the previous two veils? They are clearly not meant to represent the same thing. While multiple carvers almost certainly worked on this tomb, it was also most certainly constructed under the care of one master, so there is no justifiable reason for any stylistic anomalies, except that they are accurately reflecting different types of veils worn at that time.

Also of interest is how very square her veil is around her face; the other veils are much more rounded and follow the contours of the face. It is likely that this woman is wearing some version of the first wire headdress frame as seen in the Museum of London (see the “Shoes” page).

There is a fairly even white line around the bottom of her dress which may indicate a band of trim or a different material. The buttons down the front of her dress are unusually large and widely space, and therefore probably highly ornamental, made from some sort of expensive metal and/or gemstones.

Figure WJ1. Another thick and deeply ruffled veil. Because the veil is so thick, it is hard to tell if it is just lying on her head in that manner, or if it has been purposefully shaped to something a bit more square.

Figure WJ1. Another thick and deeply ruffled veil. Because the veil is so thick, it is hard to tell if it is just lying on her head in that manner, or if it has been purposefully shaped to something a bit more square.

Her dress also buttons up the front, although her buttons aren’t quite as big and they are spaced closer together (inferring that there are more of them as well). She has a more average mantle, resembling that of Katherine’s. This figure’s mantle, like Katherine’s, lacks the cording that is frequently seen holding the mantle across the chest. Katherine has the usual ornamental bosses at either side, which one must assume are also pins to hold it on. This figure, however, does not have any jewelry, so her mantle may be pinned with small, unadorned pins. Of course, for all we know, it was part of her actual dress and wasn’t meant to be removed.

She, like figure WB2 holds a book out for the observer to see. Her neckline is slightly more rounded than Katherine’s, but still fairly square in appearance.

Figure WL1. Yet another deep-ruffled veil, although this one only has one layer of ruffles. It does, however, like the nebula veil, have a very square shape to it, so I think we can assume that it too is being shaped by some sort of underlying wire frame.

Figure WL1. Yet another deep-ruffled veil, although this one only has one layer of ruffles. It does, however, like the nebula veil, have a very square shape to it, so I think we can assume that it too is being shaped by some sort of underlying wire frame.

The figure’s mantle is, compared to the other figures, cut unusually low and in a V-shape. We can’t see any indication of a dress above it, meaning that her dress was equally low-cut (although the neckline could be any shape). Her mantle closes fully in the front (unlike the pervious mantle, which is meant to come only to the shoulders) and has a decorative brooch, which I assume holds it closed. It has a thick band of some sort of trim around the neckline.

Figure WO2. This figure is so much like the previous one that they could be confused. However this figure has on a thin veil which is not ruffled (it’s unclear if it’s even a nebula veil). The neckline of her dress is much higher (now we’re into a situation where the neckline is unusually high for a cotehardie). Her mantle, though, is also a low-cut, V-shape, with decorative flower brooch and a heavy band of trim. It is also clearly gathered into that band.

Figure WO2. This figure is so much like the previous one that they could be confused. However this figure has on a thin veil which is not ruffled (it’s unclear if it’s even a nebula veil). The neckline of her dress is much higher (now we’re into a situation where the neckline is unusually high for a cotehardie). Her mantle, though, is also a low-cut, V-shape, with decorative flower brooch and a heavy band of trim. It is also clearly gathered into that band.

What is not so clear is this woman’s dress. It almost appears to be loose across the chest, which would mean that it’s not a cotehardie. However, I am not aware of women, like men, having two different styles of dress to chose from: cotehardies or robes. But I have read that some older women were reluctant to adopt new fashions, so this woman may be wearing an older, looser style of dress. If you look at her face, I think you can see an older woman in it, although, unlike men, there is nothing much in the way of visual cue to distinguish older women from younger.

Figure WN1. A figure similar to many of the previous ones. She wears a thin veil which, due to the blurriness of the picture, could be a nebula veil or a more modest ruffled veil.

Figure WN1. A figure similar to many of the previous ones. She wears a thin veil which, due to the blurriness of the picture, could be a nebula veil or a more modest ruffled veil.

The neckline of her dress is rather V-shaped with a small band of trim or tape-edging. The shape is mirrored by her mantle. While the mantle may have suffered some damage in places, it almost appears to have a ragged front edge. In fact, compared to the mantles of the other women, and even the men, this mantle has an unkempt look to it. It doesn’t seem to have any sort of decorative neckline, no decorative pin to hold it closed, nor is it quite as long as the other ladies’. It does appear, however, to either also open on the left, or at least have an arm hole, because the figure’s arm clearly comes through the mantle and lays on the outside of it. The appearance of it reminds me of a description I read in one of my many costuming books (i.e. don’t ask me which one(s)) of cloaks being made of fur and left with the leather to the outside. While that might explain a bit of the raggedness of her cloak, that doesn’t quite jive with Katherine and the other female figures; such a cloak was, I was given to understand, for poorer people who could not afford to cover it in material. None of the other figures seems to poor, nor was Katherine herself. However, as I mentioned before, it could just be that the edges of the mantle have been damaged and that it was a nice cloak, even if it was rather simple in appearance.

Figure WD1. Another deeply-ruffled veil, but with only two layers of ruffles and a rounded, natural shape (see my comments on the second of the wire frame headdress on the “Shoes” page; I think that all of the veils had a wire-frame support to keep them on the head, it’s just that some were rounded to match the shape of the head, while others were shaped square, as seen in some of the other figures).

Figure WD1. Another deeply-ruffled veil, but with only two layers of ruffles and a rounded, natural shape (see my comments on the second of the wire frame headdress on the “Shoes” page; I think that all of the veils had a wire-frame support to keep them on the head, it’s just that some were rounded to match the shape of the head, while others were shaped square, as seen in some of the other figures).

We’re beginning to move out of the realm of typical clothing and into the realm of unusual finds. What is unusual about this woman is the V-shaped piece at her waist. Several questions arise from this: does this represent a simple piece of trim sewn onto the dress? Is it a belt? Is it a waistline, thus making the top of the dress and the skirt two separate pieces? Or, most radically of all, is the top wholly separate from the skirt? Further along I will show you some waist-length tops which are clearly separate from the dress below. On this figure, though, it is not clear whether her top is separate or not. In any case, this is the first representation I have seen of a figure with anything like this on her dress, be it trim, a waistline, a belt, or a separate top.

She also has a rather wide piece of trim around her neckline; most representations I have seen of cotehardies are actually rather lacking in trim and other forms of decoration, aside from buttons. And yet, a reading of the excruciatingly boring “Fashion in the Age of the Black Prince” revels description after description of highly embroidered clothing. For whatever reason, I am beginning to believe that there is a discrepancy in the clothing between what was painted and what was actually worn. So why carve a trimmed-out dress, but not paint it? Is it just that we have lost so many paintings that we no longer have a diverse enough sample to show all the variations of clothing that was worn at this time? Did English people wear cotehardies that were decorated differently from Continental cotehardies? Or is it possible, given that the vast majority of surviving clothing examples come from religious texts, that women, especially, were painted wearing more demure clothes than they actually wore day-to-day? We know that the Church was constantly railing against indecent dress from this time forward; they dubbed the sideless surcoat “the Gates of Hell” because it emphasized the tight-fitting cotehardie and flattered the women’s curvaceous figure. Perhaps it is hard to find paintings of normal dress because it was a bit too racy to be depicted in a religious book, and just about all that survives to this day are religious books. After all, do we not still today wear more modest clothing when we go to church? While this tomb is in a church, it isn’t, in and of itself, a religious item, and therefore it wouldn’t necessarily be constrained by the same limitations that paintings in religious books (which were often illuminated by religious persons) would be.

Figures WI1 and WI2. Unfortunately this figure has been severely damaged. But, for those of you interested in stone carving, it does afford a glimpse into how these figures were created. The hole where the figure’s head used to be would seem to indicate to me (admittedly, I know nothing of stone carving), that the figures were each individually carved, then affixed to the tomb by way of the holes (probably some sort of metal peg set into the back of the figure, which would then insert into the hole).

Figures WI1 and WI2. Unfortunately this figure has been severely damaged. But, for those of you interested in stone carving, it does afford a glimpse into how these figures were created. The hole where the figure’s head used to be would seem to indicate to me (admittedly, I know nothing of stone carving), that the figures were each individually carved, then affixed to the tomb by way of the holes (probably some sort of metal peg set into the back of the figure, which would then insert into the hole).

This figure, like the one before, has the odd V-shaped piece at her waist. But I am reluctant to call what she’s wearing a cotehardie. Compared to the figure above and to Katherine herself, this dress is much more loose around the chest and waist (although it could just depict a rather flat-shaped woman!). It also seems to have a wide trim piece running up the front with, possibly, ornamental instead of functional buttons (hard to tell if it does have a front opening). I think that this may be a type of surcoat. When women first started wearing surcoats, they were very much like men’s, and were just sleeveless. As the 14th century progressed, the armhole dipped down deeper and became wider, until by the 1370’s or so you have the most extreme form of the surcoat, in which the top front is a narrow band of fabric and all the rest is sideless. Because we can’t be sure what decade this tomb was constructed, it’s hard to know exactly when in the evolution of the cotehardie and sideless surcoat these figures fall (although other depictions of wide-fronted sideless surcoats would seem to indicate the figures are from the middle of the cotehardie period). But I think that it’s quite possible to have some variations of the surcoat within the same time frame; I have seen surcoats with a type of cap sleeve before. Although, if this is indeed a surcoat, it appears to have full sleeves, albeit it exceedingly short ones. If it is a cotehardie in its own right, though, it has not only unusually short sleeves, but very baggy ones to boot.

The figure also has on some sort of narrow mantle which is not wide enough to come around to the front of her shoulders. In fact, it’s impossible to tell how it is attached, although I suspect that it might be sewn on along either the neckline in the back, or across the back of the neck-hole and into the shoulder seams.

What is quite clear is that the figure has on a dress underneath which has some sort of pattern (be it woven or embroidered). I feel that this, along with several other figures showing patterned clothing, gives further credence to my theory that Katherine’s dress was plain. But we also get right back around to my theory that a lot of women, perhaps, were depicted more plainly than they actually dressed day-to-day. Katherine may have wanted to show her modesty and virtue by being simply arrayed. Also, she is a very large and prominent figure, and their tomb is set directly in front of the alter, meaning it can be seen from everywhere in the church; it might have been more prudent to be depicted modestly and in a church-approved manner in such an instance. The weepers, however, are rather small and non-descript, so it could be possible to get away with making them more realistic.

Figures WM2 and WM1. At first, I thought that this figure was wearing a very loose, gown-like garment, which I would have pegged as probably being what we see showing out from underneath the mantles of the older women above. But upon closer inspection of the zoomed picture below, I can see two distinct lines falling on either side of her buttons, as well as gathering around the neckline of the dress. This is some sort of mantle or open-front surcoat; it is a separate garment from the one that has buttons down the front. Because the “outer” layer matches up so precisely at the neckline, it may very well be that this “outer” garment may be sewn directly onto the dress beneath it. Although, according to the “Goodman of Paris”, it was very important for a women to go into public being carefully dressed, with her layers arranged neatly, one over the other. A few of the other figures (plus my own experience) show that you can’t always be perfectly aligned, but it’s not outside the realm of possibility that this figure happens to be.

Figures WM2 and WM1. At first, I thought that this figure was wearing a very loose, gown-like garment, which I would have pegged as probably being what we see showing out from underneath the mantles of the older women above. But upon closer inspection of the zoomed picture below, I can see two distinct lines falling on either side of her buttons, as well as gathering around the neckline of the dress. This is some sort of mantle or open-front surcoat; it is a separate garment from the one that has buttons down the front. Because the “outer” layer matches up so precisely at the neckline, it may very well be that this “outer” garment may be sewn directly onto the dress beneath it. Although, according to the “Goodman of Paris”, it was very important for a women to go into public being carefully dressed, with her layers arranged neatly, one over the other. A few of the other figures (plus my own experience) show that you can’t always be perfectly aligned, but it’s not outside the realm of possibility that this figure happens to be.

Whether this is a mantle or open-front surcoat, it is quite unique as it clearly has sleeves. What’s more, they button all the way to the shoulder, and, in this instance, have been left unbuttoned to show off the under-sleeve.

What this garment isn’t is a second cotehardie. One, it is so far apart in the front that it could never hope to meet, even with just lacing. What’s more, the buttons on the dress beneath would make closing up the outer layer, at best, ugly-looking, and at worst, impossible.

Given that the figures are generally dressed for winter, I would suspect that this some sort of coat/mantle hybrid. It’s not meant to close in the front, like most mantles, but it has sleeves in it like a modern coat; I see no reason why the figure could not button up her “coat” sleeves if she was cold.

Note she is wearing a nebula veil.

NEW! I made a chemise with a seam that's at the top of the sleeve (i.e. it lines up with the shoulder seam). I did this because I was a bit short of fabric and so had to piece the sleeves together (it also has an underarm seam). When I was wearing it this past weekend, I noticed that the seam twists from the shoulder to the OUTSIDE of the lower arm.

What the heck does that mean? It means that I (and most people) have been putting buttons on their sleeves incorrectly. My costuming books are all up on back-seamed sleeves. Oh, this is the way they did it so the buttons would lay down the outside of the arm. But I have a dress like that and, more often than not, my buttons (which are all below the elbow), are on the UNDERSIDE of my arm. I thought the weight of my buttons (and my sleeve not being very tight) was causing the sleeve seam to twist away from where it should be. But examining the simple top-seam in my chemise explains why the back-seam method does not work with buttons on sleeves.

Look how the sleeve on this figure hangs. It's not a back-seam sleeve at all; it's a top-seam sleeve. And it's done that way so that when it's buttoned, all of the buttons are visible when the person is head-on to the viewer. Think about it: when you are looking at someone head-on, where is the outline of their arm? Not on the back of the arm. Draw a line straight down from the shoulder seam and you have the outline of the arm. Only a top-seam sleeve will give you that row of buttons all down the side of your outline, clearly visible from the front (see the Museum of London pin below). We would say that the buttons are down the center of the arm if we look at it from the side, but the view from the front is all that matters.

That's not to say that back-seamed cotehardie sleeves didn't exist; I've seen them myself in paintings. But if you are going to be putting buttons partway or all the way up the arm, trust me--put your sleeve seam at the top, aligned with the shoulder seam.

Figure WA3. As promised, the clothing is getting more interesting as we go along. We have yet another nebula veil with square shape. We also have a fairly standard-looking sideless surcoat over a cotehardie. It is hard to see, but it looks like the figure might has on a hip belt under the surcoat, which is also fairly typical.

Figure WA3. As promised, the clothing is getting more interesting as we go along. We have yet another nebula veil with square shape. We also have a fairly standard-looking sideless surcoat over a cotehardie. It is hard to see, but it looks like the figure might has on a hip belt under the surcoat, which is also fairly typical.

What is not at all typical are her sleeves. Because I can’t figure out how it would be possible to have sleeves on a sideless surcoat, I think we must assume that the sleeves are part of her cotehardie. They are excessively long and split down the front. What makes them so odd is that this same sleeve style appears on houpplandes a number of decades later, but I have never seen a split sleeve on a cotehardie before. Note that it appears to have some decorative trim around the arm opening. As houpplandes were usually lined in fur, the arm openings in the sleeves usually had some of the fur lining rolled out as trim. Cotehardies were not quite as likely to be lined in fur, although “Fashion in the Age of the Black Prince” does mention some. And given that the other figures seem to be dressed for winter, it is a distinct possibility that this figure’s cotehardie is also lined in fur.

If you look closely at the front center of her sideless surcoat, you will notice a slight gap. I think that her cotehardie is rather low cut, but that her sideless surcoat comes up a bit higher at the bust and that it has a small, cut-away section at the top before the center panel and buttons begin.

Figure WK2. This figure gets even more bizarre than the last, even though she is similarly arrayed. Making a reappearance is the deep-ruffled veil. She too has on a very typical sideless surcoat. Like the previous figure, she also has the long sleeve with front openings. Her sleeves, however, come much further forward; too far forward, in fact, to still be attached to the shoulder seam, I think. If you ignore her arms and the sleeve opening and look just above that, the sleeves look like a mantle. If you look to her right side, you will also see that the one sleeve appears to not join up in the armpit, but be opened wide and attached to the back of her outfit. This looks everything in the world like her sleeves are attached to her sideless surcoat in some sort of cross between a sleeve and a mantle. Her arm appears to be less in the sleeve (unlike the figure above), and more like it is cloaked by it.

Figure WK2. This figure gets even more bizarre than the last, even though she is similarly arrayed. Making a reappearance is the deep-ruffled veil. She too has on a very typical sideless surcoat. Like the previous figure, she also has the long sleeve with front openings. Her sleeves, however, come much further forward; too far forward, in fact, to still be attached to the shoulder seam, I think. If you ignore her arms and the sleeve opening and look just above that, the sleeves look like a mantle. If you look to her right side, you will also see that the one sleeve appears to not join up in the armpit, but be opened wide and attached to the back of her outfit. This looks everything in the world like her sleeves are attached to her sideless surcoat in some sort of cross between a sleeve and a mantle. Her arm appears to be less in the sleeve (unlike the figure above), and more like it is cloaked by it.

Of course, if it is decided that these sleeves are indeed attached to her sideless surcoat, then it does make the same a possibility for the figure above. I have to admit, when I saw these figures in person, I did initially think that their sleeves were attached to their sideless surcoats, although, even after looking at the pictures most closely, I am at a loss as to how they did it. Attaching the underarm part of the sleeve to the back of the surcoat is the only place to put it. I guess I need to add recreating one of these to my growing list of “figure out how they did it”.

Figure WF2. Finally we come to the most bizarre of all the garments. I have never heard of medieval people having a coat before, but here you have it. I dare anyone to look at this figure and tell me that she doesn’t have a fur-lined sleeveless coat on over her dress.

Figure WF2. Finally we come to the most bizarre of all the garments. I have never heard of medieval people having a coat before, but here you have it. I dare anyone to look at this figure and tell me that she doesn’t have a fur-lined sleeveless coat on over her dress.

The tear-drop shaped arm openings are similar to those of Figure WI1, although that figure has a hint of sleeves, whereas this figure does not. The coat has a collar or thick roll of trim around the high neckline, and it overlaps quite a bit to button up the front (modernly, we would not think that it overlapped more than normal, but according to “The Medieval Tailor’s Assistant”, and based on the sleeve fragments found in the London digs, people of this period tended to put their buttons on the very edge of their fabric and the buttonholes as close to the edge as possible too; neither has happened here, though).

And of course the sheer thickness of the coat and it’s shapelessness and bulkiness indicates to me, beyond a shadow of a doubt that it was lined with a heavy fur. While her sleeves may seem to have a pattern to them, I think that this is just wear and pitting in the stone and that her sleeves were not carved to indicate a pattern.

Another instance of a nebula veil.

Figure WC1. Why don’t we just make things really crazy and combine the coat with the open-front sleeves? Here it is clear that the sleeves definitely belong to the coat, not the dress underneath. It is not as readily apparent that this coat is fur lined, although it is a bit bulky at the waist and chest, which would seem to indicate that it was. It is also carved so that the trim around the edges of the coat and up the front have the distinct appearance of fur.

Figure WC1. Why don’t we just make things really crazy and combine the coat with the open-front sleeves? Here it is clear that the sleeves definitely belong to the coat, not the dress underneath. It is not as readily apparent that this coat is fur lined, although it is a bit bulky at the waist and chest, which would seem to indicate that it was. It is also carved so that the trim around the edges of the coat and up the front have the distinct appearance of fur.

Another deep-ruffled veil, although this one seems to be shorter than everyone else’s; it barely comes down past her ears.

Figure WH1. Our last figure from the tomb of Katherine and Thomas Beauchamp. Here again we have a bulk overgarment with open-front sleeves, but unlike the other two it is not so clear whether this is a waist-length coat only, or if it is a sleeved surcoat (i.e. has an attached skirt). Unlike the previous two coats, it has the frontal appearance of a sideless surcoat (only the position of the sleeves indicate that it’s not sideless at all). Due to the deep shadows under the waistband, I have to conclude that, if this coat does have an attached skirt, the top and bottom are sewn together separately into a waist. While I have never seen a cotehardie with a waist in it (with the exception of figures WD1 and WI1, whose status as to a waist is iffy), sideless surcoats often had a skirt which was separate from the top.

Figure WH1. Our last figure from the tomb of Katherine and Thomas Beauchamp. Here again we have a bulk overgarment with open-front sleeves, but unlike the other two it is not so clear whether this is a waist-length coat only, or if it is a sleeved surcoat (i.e. has an attached skirt). Unlike the previous two coats, it has the frontal appearance of a sideless surcoat (only the position of the sleeves indicate that it’s not sideless at all). Due to the deep shadows under the waistband, I have to conclude that, if this coat does have an attached skirt, the top and bottom are sewn together separately into a waist. While I have never seen a cotehardie with a waist in it (with the exception of figures WD1 and WI1, whose status as to a waist is iffy), sideless surcoats often had a skirt which was separate from the top.

I believe we have here an instance of a deep-ruffled veil, although her ruffles are more modest than any other figure’s who wears the same sort of veil.

Let’s conclude our look at the women on the tomb by tossing around some statistics (don’t worry, this won’t be gruesome; I barely passed my statistics class in high school, so I can’t make this too complicated).

Veils: From the tomb we have 7 women wearing the deep-ruffled veils, 7 women wearing the nebula veils, one with a missing head, and Katherine herself with the I-think-it’s-smocking veil. While I can’t guarantee that I got a picture of every woman, and I know I missed a few who were hidden behind a candle rack, that the majority of the figures were evenly split between the two major types of veils would seem to indicate to me that the deep-ruffled veil was fairly popular.

So why do we only see instances of the nebula veil featured in costuming books? Is it that costumers have been dismissive of this other veil because how it’s made (with starch and a hot “curling iron”) is readily apparent, while it took them a long time to figure out how to make the nebula veil, and so it is not as interesting a topic of discussion? Is it that it has been wrongfully assumed to be a nebula veil? Or have costumers, unable to explain why it differs from the nebula veil, shunted it aside as some sort of anomaly?

From what I have seen of paintings, the nebula veil seems to be the only kind of layered veil there is; I have never seen a deep-ruffled veil or even a veil like Katherine’s before. However, the nebula veil was either worn with houpplandes later, or was adopted in paintings as a symbol of status, prestige, lineage and/or office. Sideless surcoats (and cotehardies under them) continued to be shown on queens, in particular, in paintings, and on the tomb effigies of noble women long after they went out of fashion. (There were a number of women’s effigies in Westminster Abbey wearing cotehardies and sideless surcoats, even though they were buried in the 1500’s, a good 100 years after those garments went out of style for everyday wear.) Is it possible that the nebula veil alone survived this transition into a new century and into symbolism, so there are many more depictions of it, even though the ruffled veil was just as common when they both were popular? It is true that paintings increased in number in the 15th century, so if the nebula veil alone remained popular among painters, it would certainly be even more likely to appear in paintings.

Now we move on to the 15th century and two female weepers from Richard Beauchamp’s tomb (I think Richard was Thomas’s grandson). While there were more weepers than just these two on his tomb (although not nearly so many as Thomas and Katherine had), they, but for these two, were dressed in very typical 15th century houpplandes and didn’t really bring anything of interest forward (we were also in a hurry and this is not really our time period, or we would have taken more pictures).

The weepers are probably constructed the same as Robert’s effigy, meaning brass covered in gold leaf. Considering he’s been dead since 1439, and considering how churches were looted for anything precious, especially by the hated Cromwellians, I think they are in unbelievably good condition. Almost every weeper on every tomb in Westminster Abbey was completely obliterated. Of course, this church probably doesn’t see as many people in it in a year as Westminster sees in a single weekend in the summer. And weepers are, unfortunately, right at knee height, so when people lean in to look at the person on top, they knock against the people on bottom.

The weepers are probably constructed the same as Robert’s effigy, meaning brass covered in gold leaf. Considering he’s been dead since 1439, and considering how churches were looted for anything precious, especially by the hated Cromwellians, I think they are in unbelievably good condition. Almost every weeper on every tomb in Westminster Abbey was completely obliterated. Of course, this church probably doesn’t see as many people in it in a year as Westminster sees in a single weekend in the summer. And weepers are, unfortunately, right at knee height, so when people lean in to look at the person on top, they knock against the people on bottom.

This figure has a houpplande that is open in the front. She is clearly showing off some sort of underdress, but it appears, by the band at the top of this underdress, that it is made to be seen (it could also be some sort of stomacher panel). So I don’t think this is a case of a women wearing her houpplande open when it would normally have been laced closed by hidden rings or hooks-and-eyes. There is also clearly a band of trim all around the front opening of this dress, which very much calls attention to the opening itself; something not likely to have been done if the dress was really meant to be worn closed all the time. And, in fact, it doesn’t seem to have a neckline at all; it couldn’t be closed up the front if you wanted it to. I call this a houpplande because it’s not a cotehardie, and houpplandes were the only other thing (in fact, the primary thing) that was being worn at this time.

I think this figure may be wearing a cotehardie under her gown. What bits of it we can see seem to be very fitted, especially at the sleeves. It appears that the houpplande’s sleeves are pushed back to revel the underdress’s sleeves. Her outerdress does not have the voluminous amounts of fabric associated with a typical houpplande, but you can see that it’s not fitted either; there are little rolls of fabric around her belt, which are reminiscent of the sewn-in pleats that became more fashionable. The massive, angel-wing sleeves are also missing, although her sleeves are clearly looser than would have been worn on a cotehardie. She also has the typical wide houpplande belt, which is belted high above the natural waist-line. She is also wearing a mantle, which I thought would have already been out of fashion by this period. It seems to be just like the mantles worn with cotehardies, except that there is no tie across the chest, nor any decorative brooches. It looks more like a simple piece of fabric draped over her, although I’m sure it had some shaping to it (i.e. semi-circular), and it probably was held on my some small pins which aren’t evident in this sort of medium. All the same, I feel like adopting her thoughtful pose as I sit and contemplate her dress.

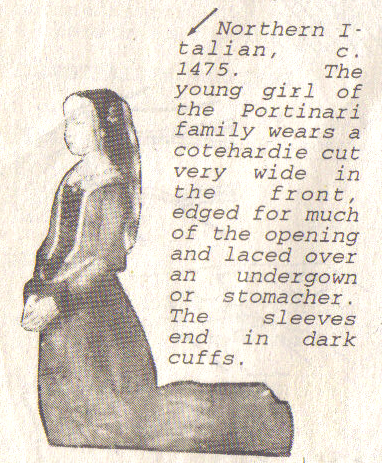

The other weeper is even more unusual in her dress. What’s that she’s wearing? Too tightly fitted to be a houpplande. It has to be some sort of weird cotehardie. While women sometimes wore their cotehardies loosely laced across the top of the bust (oh yes, those are definitely laces and not some sort of embroidered stomacher; I had a very good look at her in person), I had never seen a dress so unlaced, until I started digging through some of my costuming information and found another example:

This is a copy of a bad copy (information from Period Patterns), but you can see that this Italian girl from 1475 has a very similar dress. In my copy, I can clearly see the lines of lacing going across the dark underdress or stomacher.

This is a copy of a bad copy (information from Period Patterns), but you can see that this Italian girl from 1475 has a very similar dress. In my copy, I can clearly see the lines of lacing going across the dark underdress or stomacher.

The other example that somewhat resembles this weeper is Kass McGann (click picture to go to her website) wearing her remake of the Shinrone gown (Irish). The only problem is that the Shinrone gown is thought to be from the late 1500’s-early 1600’s. Even if it was being worn as early as the early 1500’s, that still puts it 100 years after this weeper. Of course, some people say that Irish fashion WAS 100 years behind English fashion, so maybe they are connected. Note that both the Italian girl’s dress and the Shinrone gown have a waistline (i.e. the bodice and skirt are two separate pieces). It is impossible to tell with this weeper whether her dress was also made in such a way, as her arms cover her waist, but I think--after zooming in on that tiny bit of dress that shows near her left hand--that there might be a waistline in it. The skirt seems very full, so I suspect gathering/pleating of it into the waist, like the Shinrone gown.