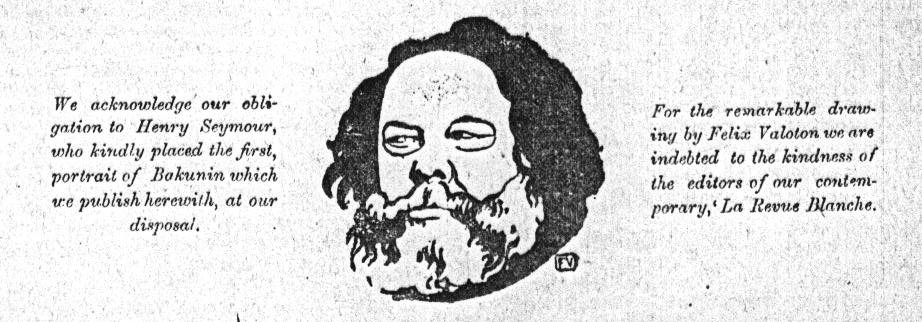

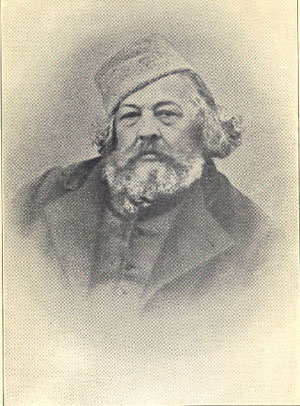

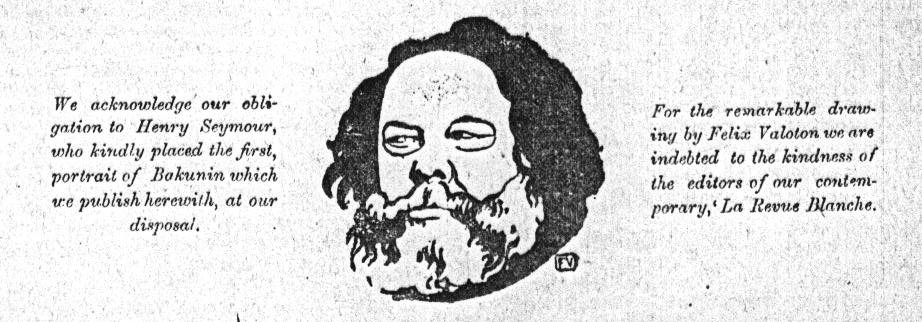

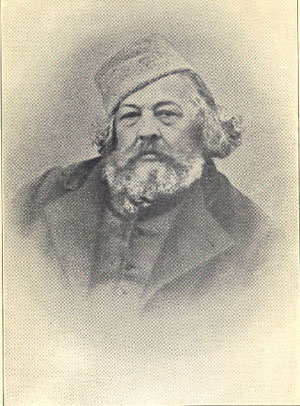

Michael Bakunin

Three of the most notable types of the revolutionistic innovators of this century are Mazzini (1808--1872), Proudhon (1809--1865), and Bakunin (1814--1876). All three were essentially "men of 48." The culmination of their teaching was then first attempted to be put in practice. But they were so much in advance of their time, that it may still be generations ere the seed they sowed shall ripen into fruit. The three were alike in restless daring, and noble aspiration. But the Italian was the refined and passionate idealist, the Frenchman the intrepid thinker, and the Russian the sturdy man of action. It is with Bakunin, as the least known in England, that I propose at present to briefly deal.

Bakunin, the founder of Russian Nihilism, was born at Torshok, in the department of Tver, in 1814. He came of an aristocratic family and was educated for military service at St.Petersburg. Even in these early years he seems to have seen that soldiers were serfs bribed by pay and decorations to keep down their fellow serfs. The artillery branch, in which he was, in common with the most favored aristocracy, had greater freedom, of thought and research than any other branch of the service, and the powerful mind of Bakunin was stimulated towards philosophy. Hegalianism was then rising in vogue, and he obtained permission to study in Germany. He visited Berlin, Dresden and Leipsic, mastering the Hegelian philosophy, which he afterwards characterised as the "Algebra of Revolution," but already inclining to the heterodox school which produced men like Ludwig Freuerbach and David Friedrich Strauss. Bakunin himself put forward several notable philosophical essays under the nom de guerre of "Jules Elisard." In 1843 he visited Paris and became acquainted with Pierre Joseph Proudhon, who in that year published his profound work on The Creation of Order in Humanity. The Russian became, a disciple of the French Anarchist, and the next few years of his life were devoted to making the Social Democratic movement also anarchist and international. His permission to reside abroad, which had only brought on him the suspicion of being a Russian spy, was recinded by the Russian Government. Instead of obeying the order to return to Russia he issued an address to Poles and Russians to unite in a Pan-Slavonic revolutionary confederation. Ten thousand roubles were offered for his arrest, and the French government expelled him. But the revolution of February 1848 brought him back to Paris, whence he rushed as a torch of revolution to Prague to stir up the Congress of Slavs. Soon after we find him in Saxony, where be became a member of the insurrectionsry government. Forced to fly from Dresden he was captured, sent to prison, and condemned to death in May 1850. His sentence was commuted to imprisonment for life. He contrived to escape into Austria, was again captured and sentenced to death, but eventually was surrendered to Russia. He was kept for several years in a dungeon in the fortress of Neva, and at length was deported to Siberia. He spent many years amid the horrors of penal servitude, but his spirit was unvanquished. He finally succeeded in escaping and walking eastward over a thousand miles, under extreme hardship, and at last reached the sea and obtained passage to Japan. From there he sailed to California, thence to New York, and in 1860 appeared in London. He had suffered innumerable hardships and adventures, had mixed with all sorts and conditions of men, from the rulers of Europe to the wild hairy Ainus, and had everywhere found that government was tyranny. He threw himself into revolutionary schemes with redoubled enthusiasm. With Hertzen he published the Kolokol, or Tocsin of Revolution. His demand for the abolition of the State drew him more and more into conflict with the Marxian wing of the revolutionary Socialist party, and in 1872 he was expelled from the Congress of the International Association, carrying however, thirty delegates with him. Meanwhile he had helped to build up the Nihilist party in Russia on the basis of undoing, present injustice without seeking to hamper, or even to guide, the natural evolution of the future. Switzerland was his only safe centre of operations, and here, with hands, heart and brain full of revolutionary schemes, he died on July 1st, 1876.

Carlo Cafiero and Elisť Reclus, in their preface to Bakunin's God and the State, say: "In Russia among the students, in Germany among the insurgents of Dresden, in Siberia among his brothers in exile, in America, in England, in France, in Switzerland, in ItaIy among all earnest men, his direct influence has been considerable. The originality of his ideas, the imagery and vehemence of his eloquence, his untiring zeal in propagandism, helped too by the natural majesty of his person and by a powerful vitality, gave Bakunin access to all the socialistic revolutionary groups, and his efforts left deep traces everywhere, even upon those who, after having welcomed him, thrust him out because of a difference of object or method." Bakunin, it is evident, was rather the stimulator than the organiser. He wrote wonderful letters, arousing the torpid and nerving the timid. Fertile in suggestion, his writings were of the nature of fragments cast off red-hot from the fiery furnace of his mind. "My life," he used to say, "is but a fragment." Most notable of the aforesaid fragments is his booklet on God and the State, in which those twin instruments of oppression are attacked with equal vehemence and vigor. It is on the pretence of divine authority that human authority is founded, and Bakunin, "apostle of destruction" as he was called by the Belgian economist Lavaleye, looked forward to the time when "human justice will be substituted for divine justice." Bakunin shows that the superstitions and stupidities of religious belief are the natural outcome of ignorance and oppression, with only the dram- shop and the church, debauchery of the body and debauchery of the mind, as the relief to a life of serfdom. But the work is accessible to all, and to those who like to come into contact with a vigorous mind I say:--"Read it; and if you do not like it, Read it again."