|

A Chaste Maid in Cheapside By Thomas Middleton |

| ||||||||

|

Directed by William Gaskill February

1966

| |||||||||

The

Cast

| |||||||||

|

Sir Walter

Whorehound…. Davy (his

servant)…….…. Welshwoman…………….…. Sir Oliver

Kix…………………. Lady Kix………………………. Allwit……………………………. Mrs. Allwit…………………….. Wat…………………………….. Nick………………………….…. Wetnurse…………………….. Touchwood

Senior………… |

Sebastian

Shaw Joseph Grieg Nerys Hughes Ronald

Pickup Avril Elgar Christopher

Benjamin Frances Cuka William

Stewart Dennis

Waterman Nerys Hughes Tony Selby |

Mrs.

Touchwood (his wife)…………… Touchwood

Junior (his brother)……. Yellowhammer

(a goldsmith)……….. Maudlin (his

wife)………………………… Moll (his

daughter)………………………. Tim (his

son)……………………………… Two

Promoters………………………….. Country Girl………………………………... Two Puritans………………………………. Parson……………………………………….. |

Gillian

Martell John Castle Bernard

Gallagher Jean Boht Barbara

Ferris Victor Henry Richard

Butler, Timothy Carlton Lucy Fleming Gwen Nelson,

Gillian Martell Roger Booth |

||||||

|

Plays and Players March 1966 |

“Jacobean Bawdy” Reviewed by John Russell Taylor |

||||||||

|

All things considered, there is really

a lot to be said for commerce. If there is anything the history of the arts teaches

us unarguably, it is that fine intentions butter no parsnips: art emerges

much more often from the efforts of some entirely unpretentious craftsman

meeting a deadline than from the lofty aspirations of a self-appointed artist

calmly sitting in his ivory tower bent on producing art. Middleton always

seems to me an excellent practical example of this: he had fewer recorded

pretensions than any other Elizabethan-Jacobean dramatist and from what

little we know of him he seems to have been content simply to pour out plays

(alone or in collaboration), pageants, pamphlets and poems just as demand

offered, and with not the slightest thought that he might be producing - as

Webster, Jonson and even Shakespeare certainly thought-works of art which

could last for hundreds of years. And yet, perhaps because of this, his plays

remain as revivable and continuingly entertaining as almost any of the

period, and to my mind considerably more so than the more literary,

deliberately artistic plays of Webster or Jonson. I have enjoyed productions of The Changeling and Women

Beware Women as much, I think, as any modern revivals of Jacobean drama I

can think of (it can hardly be chance, incidentally, that these were the two

which, enticingly billed as bloody melodrama, came over so well to mass

audiences on independent television last year), while I am sure that A

Trick to Catch the Old One and perhaps Michaelmas Term would

revive as well. I would have thought so too, I must say, about A Chaste

Maid in Cheapside, and so I am left wondering why, with all the auguries

so favourable, I found the net result of the Royal Court's new production so

unsatisfactory. Certainly the

programme note, which presumably represents the views of the play's director,

William Gaskill, strikes an encouraging note. Middleton is presented to us as

the author of 'bawdy plays. . .venery and laughter, to keep you in an afternoon

from dice at home in your chambers'. Which is true of this play at least, but

hardly true of the way it is here treated. There is nothing wrong with bawdy

humour-far from it-and there need be nothing embarrassing about its delivery

in front of a reasonably intelligent, sophisticated audience such as the

Royal Court usually attracts, provided it is put over with conviction and

even relish. But the trouble here is that the production is, in general, slow and

lacking in buoyancy, while the individual actors called upon to deliver the

bawdier lines look so shame-faced about it that instead of laughing as we

should we come merely to share their embarrassment. Observe, for instance,

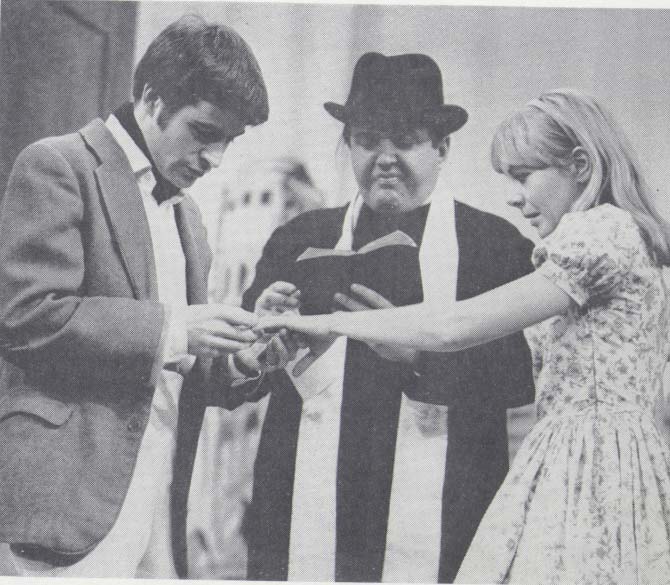

John Castle, as stiff-necked, correct, a young Englishman as you could hope

to find, trying to put over the suggestive double-entendres given to the

romantic hero when he is busy gulling a wedding ring for his beloved out of

her unwitting goldsmith father; as he mumbles the lines about having her

measure concealed about his person and so on, he looks as though he could

sink through the floor, and any unholy enjoyment we might otherwise derive

from them sinks with him. Christopher Benjamin, as Allwit, the joyful cuckold

well-paid to bring up his bastards discreetly and hold his tongue, does a

little better with his rougher pieces of invective, but even he seems to be

bracing himself as though to withstand some outraged reactions from the

audience, and so again his more outrageous sallies at the expense of the

greedy gossips fall flat. However, I must

not seem to suggest that the play stands or falls entirely on its blue jokes.

They are not so many or so constant as that. And anyway, they are not there

for themselves alone: an important part of their function is to fill out the

rich, varied and vividly idiomatic picture of London life at the start of the

17th century which Middleton presents. It is more as a panorama than anything

else that the play works: the plot, full of confidence tricks, disguises, substitutions

and last-minute revelations, is neither here nor there; some fairly drastic

editing of the sprawling text has not, perhaps, greatly helped matters, but

anyway Middleton's strength in this play lies more in the individual pearls

than in the precise way they are strung together. Unfortunately, a

number of details in this production seem designed with almost willful

perversity to minimize the very qualities in which the play itself is

strongest. The set, for instance, a ruthlessly hard, bare design with a lot

of wooden boards relieved only by two almost equally undecorated,

uncompromising blocks representing houses at the back and a curtain beyond

with a greatly enlarged engraving of Jacobean London on it, is a chillingly

uninviting stage upon which to spread the expansive, luridly coloured wares

the dramatist has to sell. To make matters worse, the costumes in which this

very exactly, essentially period piece is played are made vaguely (very

vaguely) Edwardian, thereby getting the worst of both worlds: remote enough

in period to make us see it as a period piece, modern enough to make us overconscious

of the disparity between how the characters look and how they talk. What the

purpose of all this may be, beyond simple economy, I could not say; but if

economy was uppermost in the producer's mind, it was surely false economy,

since this is the sort of play which must be done absolutely right or not at

all. As will be

gathered, I did not enjoy myself much at A Chaste Maid in Cheapside, and

I am more than usually at a loss to account for the ecstasy into which it

threw most first night critics. Perhaps I suffered from some extreme

second-night reaction on the part of the actors, but even so I cannot think

that the production's general terms of reference could ever permit it to be

absolutely first-rate. As usual, even in the adverse conditions I have

outlined, I still admired some of the company's acting, particularly that of

Ronald Pickup in the unlikely role of the ageing and rather idiotic knight

Sir Oliver Kix, who cannot manage to impregnate his wife unaided, however

hard he may try, that of Avril Elgar as his hatchet-faced wife, and that of

Frances Cuka, Joseph Greig and Gwen Nelson in smaller roles. But in general

the whole thing remained, alas, more interesting as a demonstration of how

not to manage Jacobean comedy than entertaining in any less specialized

fashion. |

|||||||||

| |||||||||