Genealogy

EXCERPT 2

Genealogy

EXCERPT 2

____________________The Pacific Ocean put a stop to my grandfather’s long trek from Yugoslavia. His long treks first began when he was a boy in the village of Ljubinje in the province of Hercegovina. He wandered in the rugged landscape where goat bells clanked on the rocky hillsides in a timeless Mediterranean tableau. The same aroma of sarma, or stuffed cabbage and bell pepper stew, led him home from his boyhood wanderings as it did me, as I wandered dreamily in Lytle Creek wash next to my house. My grandfather Risto Radic had three brothers, Stjepan, Boško, and Stanko, who were to remain near the village of Ljubinje and nearby Trebinje their entire lives, two of which stretched out to over one hundred years. (My grandfather died at the age of one hundred and two.) But the poverty and tedious rural life soon exasperated young Risto, who would be the only one of the four brothers to emigrate. Stubborn as a mule, he said good-by to his family in Ljubinje one day and began the hundred-kilometer walk to Mostar (above), capital city of Hercegovina, where he planned to get an education and make his fortune. Entering the city of Mostar for the first time, he saw the bridge (most) over the Neretva river and its pointed arch, built in the sixteenth century by the Turkish invaders. The oriental arch crossed the river bridging the occident and the orient with mingled dreams.

It had only been a few decades earlier when Mostar was decked out by the Turks with the heads of nine fallen Serbian warriors of the Petrovic clan, traditional chieftain family of Crna Gora (Montenegro). Crna Gora was the last stronghold of Serbian independence against the powerful Ottoman Turks, whom they had resisted for centuries with fierce warrior clans, although greatly out-numbered. During twenty years of this succesful resistance Crna Gora was ruled by the warrior-bishop-prince-bard Petar II Petrovic Njegoš (left), considered the greatest poet in the Serbo-croat language. His main opus, The Mountain Wreath, emanates his anguish over this state of ceaseless warfare, and the unhappy destiny of the Montenegrin Serbs. Such was the destiny of Njegoš’ fifteen-year-old brother Joko, killed in battle along with eight other kinsmen and thirty more Serbs, by Turks fighting under the renowned Smaďl Aga Cengic, lord of Gacko. The severed heads of the Serbs were displayed in Mostar, and back in Crna Gora a popular song was heard:On Grahovo’s wide and spacious plain But Prince Njegoš received his vengeance. In an attack led by Novica Cerovic, Smaďl Aga and his troops were surprised and the Turkish chieftain was killed along with forty of his men. The first Serbian warrior to reach the corpse of the great Turk, as if “counting coup”, was Mirko Aleksic, who cut off his head. They returned to Crna Gora with the head, which, after being washed and combed as was the custom, was given to the Prince. He tossed the head into the air like an apple. Catching it, the poet said,

Of Petrović men full nine were slain

By Cengić Aga’s gleaming sword,

To the shame of Crna Gora’s lord.

– So you too have come my way, poor Smaďl!

It was a handsome head with the thick graying moustache of a man of fifty, which was to adorn the ramparts of the Tablja Tower over Crna Gora’s capital. In Mostar, Ali Pasha rejoiced secretly over the death of his rival.42 The Croatian poet Ivan Mažuranic (1814 -1890) immortalized this story in the epic poem The Death of Smaďl Aga Cengić.

The Turks were repulsed from Mostar by the Austrians. The severed heads displayed on the bridge were lost and forgotten when my grandmother Tamara Bukvic went to school there. It was a time of uneasy peace in the Austro-Hungarian empire, not so much “peace” as a prolonged cease-fire. The high school in Mostar was the cradle of several secret societies, collectively known as the Young Bosnians, some of whom were to be the architects of the assassination of Franz Ferdinand in 1914. The common goal of these high school boys was the destruction of the Austro-Hungarian empire, and I’ll be damned if they didn’t succeed! Mostar was a hair’s breadth away from being the site of the assassination of emperor Franz Joseph. The tyrant passed so close to the assassin Zerajic at the crowded train station that the latter could almost touch him. But the emperor was spared and another four years would pass before another assassin’s bullet would bring down his nephew Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo.

Zerajic instead tried to assassinate the governor of Bosnia, but after firing five shots and missing all of them, he committed suicide on the bridge over the Miljacka in Sarajevo. Hours before his fiasco, Zerajic met a friend in a restaurant, exitedly telling him of nearly brushing the emperor’s sleeve at the Mostar train station. Lamenting the plight of the Southern Slavs, they both admitted that they were slaves, that it was their destiny to show courage only in crowds, rushing like zealots into the maw of doom, as did the great Serbian army at the battle of Kosovo Polje in 1389. Zerajic continued: “In crowds we rush on the enemy’s naked sword. The tribes are then proud of the bravery of their members. But we have no individual bravery. For this a higher culture is needed, stronger feelings than mere tribal pride. We have no man who, all alone, asking no one, could perform a memorable deed.” 43 My grandfather and father were also filled with “mere tribal pride”, the same vice which would lay waste Yugoslavia in the 1990s.

As assassins go, Gavrilo Princep (1895-1918) had far better luck than Zerajic. Princep today is considered a hero by some, a lunatic by others. Whatever the case, even dying in utter misery of tuberculosis in a dark dungeon, as his very skin rotted away, his apparent defeat camouflaged this astounding success: not only did this Serb high school boy succeed in his aim to destroy the hated Hapsburg dynasty, and forever terminate the Austro-Hungarian empire, but he also succeeded in initiating the destruction of all four empires tyrannizing over Europe at the time: Kaiser Wilhelm’s empire centered in Berlin, Czar Nicholas II’s empire centered in Moscow, and the most hated Ottoman Turk empire centered in Constantinople, oppressing Yugoslavia for four grisly centuries. Such was Gavrilo Princep’s astounding success achieved with one single bullet.

Risto Radic was soon a part of the busy life of bazaars in Mostar, haggling over vegetables (as he was to do in California), punctuated by a tiny cup of super strong Turkish coffee, or a slender glass of yellow šljivovica (plum brandy). Muslim minarets protruded from behind red tile roofs, from where the arabesque call to prayer could be heard each afternoon. He was soon eyeing a merchant’s daughter, Tamara Bukvic, the sweet woman I was to call “Baba” (“grandma”) half a century later. She went to the same bazaar as Risto, or perhaps to another, but an erotic interest was kindled in him which brought him to the rash action of proposing to the girl. The Austro-Hungarian army interrupted the wedding which was postponed as my grandfather served they Austrian emperor in the ranks. The land of the Southern Slavs began to stink of war, even before Gavrilo Princep (one of the Young Bosnians) assassinated the archduke.

I visited Mostar in 1972 and stayed with relatives. It was a charming town, and when I crossed the old Turkish bridge (stari most) it seemed as if I walked into a fairy tale. After nine years of work the bridge was completed in 1566, designed by Ottoman architect Mimar Hayruddin. In a few instants it was destroyed on November 9, 1993 after being bombarded by a Croatian army tank during the Bosnian war. This fit of perverted lunacy, which brought about the worst devastation and slaughter in Europe since World War II, was the result of “mere tribal pride”, a mass-suicide that occurred simultaneously with my father’s own suicide.

The name Radic (pronounced Radich) has a very bad ring to it today when considering the fraticidal wars in Yugoslavia since Gavrilo Princep fired that fatal shot. One of the commanders of the infamous Omarska death camp has recently been arrested and sent to trial for war crimes at the tribunal in Hague. His name is Mladen Radic. He is accused of having “murdered, raped, tortured, beaten and in other ways inflicted constant humiliation on the inmates.” Miroslav Radic was commander of the Serb brigade that attacked and occupied the Croatian city Vukovar. He is indicted at the Hague tribunal for the mass-murder of 200 Croats and other non-Serbs. His victims were abducted from a hospital and taken to a nearby pig farm where most were shot and buried in a mass grave. After eight years of hiding Miroslav Radic surrendered to the Hague war crimes tribunal.

I do not know how many sons Risto’s three brothers had, nor if the above two Radic are kin, but they join in infamy another Serb war criminal with the same last name: Radomir Radic. This latter was shot before a firing squad in 1946 for war crimes committed in Bosnia during World War II, along with the chetnik (ultra-nationalist Serb) commander Mihailovic. Photos of Radomir Radic bear an uncanny resemblance to my own father, Desimir Radic. A fine kettle of fish! When confronted with the name Radic, posterity shall now ask: “Which one, the war criminal or the artist?” Had it not been too late in my career, I could have taken my mother’s (Greek) maiden name, as did Picasso. Theo Sarris – yes, a much nicer ring to it. (Thanks, Mom, that I am not 100% Serb!)

Risto deserted, made loans he never repaid, married Mara Bukvić hastily, and set out with his new bride for New York City. *** AMERIKA ***! Old Sterija had said that there was as much gold in Amerika as dry beans in Europe. Much monies: Mnogo novac! After a year in New York City the young couple began to get restless. They had saved up some money and were ready to depart again. They continued the migration to warmer shores begun by ancient sun-hungry nomads who left damp valleys along the Volga for the sunny Adriatic coast. The two Southern Slavs decided to go to Southern California, leaving a tenement flat in Brooklyn for the sunny Pacific coast.

My grandparents were part of the last of three stages of Yugoslav immigration to Amerika, which supposedly began as early as the fifteenth century, if the legend of the two sailors from Dubrovnik accompanying Colombus is true. A century later, a Croatian ship was wrecked off the coast of North Carolina near the Roanoke colony of Sir Walter Raleigh, the survivors of which settled near-by, their descendants living today in Robeson county. Among the Yugoslav immigrants were many catholic missionaries who would help other European missionaries to lay waste aboriginal cultures. One such was father Konscak who drew the first map of Baja California and did his best to convert the original Californians to the “gentle yoke of catholicism”. Another was bishop Baraga who wrote a Chippewa dictionary and a christian prayer-book in the Ottawa language, thus helping to destroy the Ottawa's oral tradition dating from time immemorial.

As the Austro-Hungarian empire declined, the Southern Slavs came in increasing numbers: Serbs, Bosnians, Macedonians, Montenegrins, Dalmatians, Croats and Slovenes. The terrible ordeals of their voyages did not end upon arrival in Amerika, and very often they increased, due to the racism and xenophobia of established Americans (themselves immigrants or offspring of immigrants). The exodus from Yugoslavia was so overwhelming that one of the greatest Serbian poets, Aleksa Santic, wrote a drama entitled Stay Here! in an attempt to curb the flow. The Dalmatians, age-old mariners, soon, found that the Pacific coast of California resembled their homeland, and in San Pedro they began a fishing industry similar to the one practiced on the Adriatic islands of Brac, Hvar, Korcula and Vis. Along with the Dalmations who established themselves in Southern California were many Serbs, among whom were Risto and Mara.

The mystery that led them to southern California is like the mystery which leads the Pacific salmon up raging torrential rivers to the exact location where she was spawned. In my hometown San Bernardino Risto and Mara had found the one city on the North American continent most resembling Mostar. Both places are surrounded by vineyards and snow-capped mountains (in spite of the warm climates). Both are nestled in valleys about one hundred kilometers from large port-cities with old histories: Dubrovnik and Los Angeles. Both are situated in the southern parts of geographically long countries with long western coastlines. These coastlines are both mountainous and irregular, spanning two distinct climactic regions, skirted by seas over whose horizons lie scattered island archepelagos: Hvar, Santa Catalina, Korcula, San Clemente, Brac, and Santa Cruz. Both places are richly endowed with natural resources, mountain ranges, cold brooks, streams and rivers in which salmon (mladica in Serbo-croat) once flourished before industries polluted them. Both places are cradles of ancient bardic traditions and wandering epic singers like the Mohave bard Avépuya (Dead Rattlesnake), Tešan Podrugovic, the Yurok bard K'e-tse'kwel (Lame Billy of Weitspus), and Philip Višnjic, the blind singer of Grk. Both places have been modernized by vain men who lust after wealth and rank, and who founder in inadequate political theories, ignorant of nature’s Way. Both places are known to have earthquakes and uncertain skies where Coyote and his elder brother Wolf (Dabog the Lame) limp after their repective thefts of Promethean fire, which burned their paws.

My grandparents quickly adapted to the base spectacle which is the perpetual gold-rush of California, to the shallowness of the new society built so precariously on ancient homelands by violent invaders. Risto spent his time chasing chimera, selling ripe or rotten vegetables, and beating his wife for talking to the neighbors. She was forbidden by him to learn English or to go visit people unaccompanied. It is said that he once wounded her in the leg with a gunshot for disobeying his orders. I don’t know if this is true or not, but the fact remains that Risto was a cruel unloving husband, to such an extent that his children were forced to forbid his coming home to live. He was skeptical about chukons, a derogatory name used by some Yugoslavs to denote non-Yugoslavs. Even among themselves there were hatreds. My Serb father was raised to despise Croats, never knowing why. Despite his prejudices, Risto was unaware of his own baseness which, many decades later, would poison the pen of his grandson. But he learned quickly that racism and xenophobia were part and parcel of the American Dream. He was a bohunk, a derogatory term from Amerika’s work-a-day slang meaning “Yugoslav”, like “wop” for Italians and “kraut” for Germans. However, in spite of her husband’s typical European style tyranny (which my father would inherit) Mara kept her angelic humor for her whole life and was a warm and loving mother to her five children, one of whom she gave birth to alone and unaided in a walk-in closet.

My Serbian Baba could speak very little English. Her husband forbid it, and the little she knew is reminiscent of an English conversation book used by Serbian immigrants to Amerika:

Гојн ту трај јур лоқ?

(gojn tu traj jur lok = Going to try your luck?)Хао лонг ју вил римејн?

(hao long ju vil rimejn = How long will you remain?)Ај донт но.

(aj dont no = I don’t know.)44Risto and Mara’s first-born was named after a Serbian king, Desimir, and grew up with his siblings in a Los Angeles suburb speaking only Serbo-croat at home. This was my father.

The maternal side of my ethnic heritage is much more confusing and vague. The little I have been able to piece together forms a fabric connecting me to many European peoples. I am the mongrel par excellence. Anargyros “Harry” Sarris was a Greek dandy who came to *** AMERIKA *** as a sixteen-year-old with much the same expectations as Risto. My mother tells me that he may have had a French mother. He was from Kranidi in Peloponnesos, and is listed as a passenger on the S.S. Roma sailing from Naples on March 13, 1907, which arrived in New York City on March 26th. The U.S. Immigration Office in New York recorded in its registry that he had $15 in his pocket and was on his way to join his brother Antoine in Delaware. (No one in my family has any knowledge of Antoine.) In the family photographs Harry looks out with his roguish baby-face, conforming to what is known by modern standards as being “handsome”. Escorted by the swirling hurly-burly of spirits who were mischievously (and against my will) plotting to bring me to life, Harry Sarris went to Michigan state. There he met Mary McFarren, who was quite a mixture of northern Europeans: Scottish, Irish, English and German.[...]

When Samuel Johnson travelled with the Scotsman James Boswell in Scotland, the American Revolution was only a few years away. Johnson was saddened by the sturdy, self-reliant men and women of Scotland who were forced to emigrate to America due to poverty and exploitation by the English. At an inn in the Scottish highlands Johnson and Boswell witnessed the local dance called “America”. One by one all began swirling in the new dance, anticipating the frenzy of emigration.

In the next century, my great-great grandfather Matthew McFarren left Scotland forever and emigrated to America. His son Oneida was born in Ohio in 1861. He became a wanderer and jack-of-all-trades, house-painter, farm hand and even an extra in a couple of Hollywood movies. (His left thumb was missing, and he said he shot it off when shooting a gun working in a western film. When he was 91 he was hit by a car and broke his hip. He died three weeks later.

Mary McFarren’s sturdy mother had hopped through a long life on one leg. The other was mangled in an accident when she was two years old. As a toddler Great-grandma Nora (Willaman) McFarren walked into a stable in Ohio, and the wee tirryfyke of a lassie was found trampled beneath the hooves of a cow. My great-uncle Ted McFarren, Nora’s thirteenth child, wrote the following:

“My mother Nora’s crippled leg was from a cow stepping on her when she was two years old. Her leg became infected with tuberculosis of the bone. My father, Oneida, was a wanderer and did not stick around to help raise us kids. Because of her disability and using a crutch my mother wasn’t able to hold a job. She earned money by crocheting doilies and tablecloths. I always say we were raised with a crochet hook. At the time of her death, my mother was living in a cottage on my property in Akron. I had taken her to Ontario for a visit and she died there on 6/12/1946. She was buried in Dalton, Ohio. When I cleaned out her cottage I found some diaries she had kept.”

Four generations:

John Willaman, his daughter Nora McFarren,

her daughter Mary McFarren (standing),

Mary's son Theodore Sarris ("Uncle Ted")As an adult, great-grandma's dangling sock of a boneless leg was no longer than it was on the day of the accident. But such trifles did not stop her from giving birth to fourteen children. Nora McFarren lived several years in San Francisco on and off, coming back many times on her travels over the country. Her husband Oneida was the classical American bum. It is astonishing that, with a wanderer as a husband, and being a traveler herself, Oneida was “available” often enough to sire fourteen children by her. As great-uncle Ted wrote, he did nothing to help raise the children, and Nora was obliged to use her bountious wits to the maximum survive. When a carnival came to the Ohio town where she lived with her children, several of its performers boarded with Nora. Harry Weber (a tatoo artist), Tex, Bakey and Chief Little Bird (a Winnebago lasso expert) were among those mentioned in Nora’s diary. In a pocket in the back of Nora’s diary, Ted found a newspaper article she had saved about his sister Viola, Nora’s first-born, and their father.

Although he was a vagabond and a bum who abandoned his family, Oneida had “religious principles”. His daughter Viola found a job in a restaurant waiting tables, and when she earned enough money she bought a pair of high-heeled slippers. The newspaper article scoffed at Oneida’s religious objection to his daughter’s high-heeled slippers, and that he may have had a better hearing with the family if he had been more than a “free lodger”. There was a quarrel, and Viola “stuck her slipper in her father’s eye - after first removing it.” Nora entered the fray, who “when she saw the slipper in her husband’s eye, struck him with the nether end of her crutch. As the father was choking the daughter, neighbors interfered.”

Great-uncle Ted, who cared for Nora in her old age, wrote this about Oneida McFarren: “My father Oneida was a wanderer. The first time I saw him I was a pre-schooler. A man [Oneida] came to the door and behind him was the biggest animal I had ever seen. It was a mule. He had walked and rode it all the way from Tennessee. He asked my mother to let him leave it for a while. He never came back for it. Later a man in one of the first automobiles drove by and backed up and pulled into the yard. He asked my mother Nora how much she would take for the mule. He ended up trading her a jersey cow for the mule. That was the first time I had tasted fresh milk.”

Nora and Oneida’s fifth child was my grandmother Mary McFarren, born in Indiana. The federal census of 1910 lists her at age fourteen as “servant” for Isaiah and Minerva Byall in Ohio. (My memories of her are more that she was most often served.) My uncle Harry wrote this about his mother: “My mother Mary had performed in a circus act with two other girls at age 18, a high-wire act with bicycle. They were billed as the ‘Nelson Sisters’. She quit after she fell and hurt her leg.”

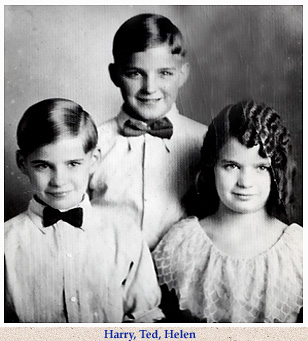

Mary married her Greek dandy, and then posed with him for the photographer (see above). She wore a wide-brimmed turn-of-the-century hat, with a flamboyant boa feather coiled around her neck. Harry the Greek had a snappy three-piece suit complete with spats and a jaunty panama hat. Theodore, Harry and Helen were born. Then the marriage soured, and after the third child was born, they divorced and Harry (Anargyros) disappeared from her life. My mother recalled: “I was one year old when my parents separated. My mother and step-father, George Stout, got together in Detroit when I was five (1925), and moved to the Lake at Michigan Center. My brothers were with our father (they were boarded with some Greek people my father knew in Detroit). Soon after the move my mother brought them to the Lake to live with us. We had about six years together there.”

Harry the Greek hardly ever saw his daughter, who was often boarded out in exchange for housework. She secretly longed for him. In one home she experienced the warmth of a kind and caring family she never knew with her mother and step-father. Her brothers were speaking fluent Greek in Detroit, but forgot every word as adults. Their father's fate can be read in this excerpt from a Flint Michigan newspaper article for October 6, 1957: “Man and Woman Killed When Car Rams Train: An elderly Detroit man and woman were killed instantly at 4:40 P.M. Saturday when their car crashed into the side of a moving Grand Trunk freight train at a crossing on M-21, a mile east of M-13 in Genesee county. Dead are Harry [Anargyros] Sarris, 61, and Miss Minnie I. Hartog, about 70, both of Detroit.”

Anargyros and his mother-in-law Nora

The three boisterous children loved to swim in the near-by lake like tadpoles, to play hide-and-go-seek, and hunt muskrats and sell the hides for a dollar a piece. (The meat as well was valued by the hungry children, and prepared in the right way, made a good savory dish, as my uncle Ted says.) They caught snapping turtles at Willow Point and sold them to Mike Dorsey the boatman. After a long hard row in the boat past Goat Island they feasted on the wild blueberries at a secret spot. They rowed against the wind, thinking they would raise a makeshift sail and sail back home, but the wind changed directions and they had a hard row home. Mom often told us that she doubted the rich kids had such a fun life. Once, the school superintendent unwittingly cut some sticks of poison sumac for a game the kids were playing. They all got a rash, their faces swelling up until they couldn't open their eyes, which they aggravated by rubbing with their infected fingers. Two twin cousins died one winter ice-skating on the lake. One fell through the ice and held on to the other twin, dragging him down with him.

Back at the lakeside cottage, Mary entertained men, took their money in exchange for her fast-fading charms, and neglected her children. A certain Mister Stout, a stern truck-driver, whose brother “Shorty” once made obscene advances to the little girl, moved into the household at the Lake. A few more dollars in the house won't hurt. He was especially mean to his step-children, beating the two boys, but fortunately he was often away driving his truck, as Mary brewed moonshine in the bath-tub. (You see, some mindless politicians in Washington had gotten it into their brains to pass the Prohibition Act, and although bungling can be tolerated in running the country, to take away a citizen’s last source of oubli is the last straw!) As a child I was to know Mister Stout as “grandpa”, who was left a widower after Mary died peacefully in California in her electric vibrating armchair. Not long before his death, Mister Stout asked my divorced mother, his step-daughter, to marry him…

Considering the scenes of her mother arguing and screaming with her step-father at the lake (a habit they were to continue for the rest of their thirty-odd years together), the little girl tried to be away as often as she was permitted, spending long hours playing hide-and-go-seek in the lake with her friends. She became a good swimmer (especially under water) and loved to hide from whoever was “it” among the reeds and cattails, able to hold her breath for a long time if the serious game required it. (Any one caught above water was “it”.) They played “fox and geese” in the tracks they made in the first snow to fall on the frozen lake. Her newly arrived brothers were ridiculed as the “city boys” from Detroit, which led to uncle Ted having a fight with Earl soon after he arrived. (Uncle Ted was a Golden Gloves boxer, so I guess Earl got the worst of it.) Uncle Harry began to steal cars, ending up in prison.

self-portrait of my mother at 19[...]Her first job had been in a tire factory during World War II where she worked like a man with heavy labor. When Tony was born in Jackson, Michigan of a part-Cherokee father, she had been seriously studying art. She was precociously skilled in graphite pencil drawings and did many youthful self-portraits. She continued her art studies in Los Angeles, where she now lived with little Tony after the divorce with Gus. She took the train from Michigan this time, having hitch-hiked all the way with her rambunctious mother the first time. She got an offer to illustrate biological textbooks, and began peering into a microscope and recording what she saw with watercolors. It was work that gave her great satisfaction. She saved some of her watercolors of cell tissues revealing to my learning eyes her patient skill and resourcefulness.[...]

She knew little of her vanished father except that he had left her with a Greek name, the name of the most remembered of Greek queens, enigmatic phantom of womanhood, cuckold-maker who vanished from the arms of of both Menelaus and Faust, leaving only her veil and robe in the latter’s arms after they had conceived Euphorion (a Byronic being who never knows old age). The bards of Mycenae and Achaea sang how Helena realized her fatal name, “destroyer of ships”, from hele, implying “destroy”, and na, “ships”. (We should not always believe poets.) Helen excelled in her studies and was on the honor roll each year, finding in school a haven from the dark realities of her home. The dark-haired girl began to show signs of an artistic gift.

(Grateful acknowledgement to my couisin Diana Day, uncle Harry’s daughter, for much of the above information). .

Helen Ruth Sarris

December 4, 1920 - April 24, 2003