“…what I have to say is of mine own making.”

Syukhtun Editions

“…what I have to say is of mine own making.”

(William Shakespeare himself speaking

on stage as the dramatist who wrote

Second Part of King Henry IV)

courtesy British Library

Improbability | Deification | The female bard | Tradition of denial

He looms in each age like the Ghost of King Hamlet, a role which he is said to have played on stage. Who he was is unknown. The line from the Epilogue of Henry IV above he delivered as an actor on stage. In the audience was Queen Elizabeth (Contested Will). Certain people claim that Will Shakespeare from Stratford-upon-Avon was simply too common to have had such keen knowledge of the world and command of the language that overwhelmed all his contemporaries and users of English before and after him. They insist that someone much more educated and worldly must have written his Works. I became acquainted with them gradually over the decades since childhood, and scoured biographies to learn who he was. I do not doubt his authorship, even though some very brilliant people have and do so still today. The most recent of these is Joseph Atwill, whose Shakespeare’s Secret Messiah was published this year (2014), and who mocks “William Shagspere” (from a list of a dozen or more alternative Elizabethan spellings) as being “completely illiterate.” He annnounces this most astonishing news without providing any documentation. Two paragraphs down from claiming that Shakespeare was “illiterate” Atwill remarks that a major literary figure who knew him, Ben Jonson, called him a “plagiarist.” How can one be illiterate and a plagiarist at the same time?

Shakespeare from Stratford is not considered educated enough to be the author of the plays and poems because he did not attend the university as did Christopher Marlowe and other candidates for authorship. Nor did the other major playwright – on the other side of the Atlantic – have any fondness for the university, despite the unspoken decree that only such credentials can give an artist credibility. Flowering into dramatic maturity not in London, but in New London, swimming in the “other” Thames, Eugene O’Neill’s failed attempt at Princeton in 1906, made him wonder: “Why can’t our education respond logically to our needs? [...] I think that I felt there [Princeton], instinctively, that we were not in touch with life or on the trail of the real things.” (O’Neill: Son and Playwright, Louis Sheaffer, Little, Brown and Company, Boston, 1968.) The irony is that this great playwright entered the university as one of the best-read members of his class, with one of the best minds, and yet he was the least qualified to succeed at the university. Yes, knowledge can be acquired elsewhere than at the university.

Highly educated people who are thoroughly at home in the academic world have proclaimed, with all the weighty prestige of their calling (as did Sigmund Freud), that Edward de Vere – or Candidate X – wrote Shakespeare’s plays and poems. A university education did not however provide them with the wisdom to avoid chasing the chimeras of these some 86 candidates for authorship, and wasting copious amounts of vital time and energy on a life-long wild-goose chase. However, some “anti-Stratfordians” refrain from postively identifying unlikely candidates like Edward de Vere, or Candidate X, and judiciously proceed with caution. Others end up making laughing stocks of themselves. At least one of these famous “anti-Stratfordians” went insane.

On the website DoubtAboutWill “anti-Stratfordian” celebrities like Mark Twain, Henry James, Sigmund Freud, Walt Whitman and others are listed as an inspiration for visitors to the website to sign their “Declaration of Reasonable Doubt.” However, in emulating Mark Twain, I must believe that Francis Bacon wrote the Works. In emulating Sigmund Freud, I must be convinced that Edward de Vere (Earl of Oxford) wrote them. Is it really a good idea? In the tradition of these illustrious “anti-Stratfordians,” Shakespeare’s Secret Messiah argues that a “comic system” throughout the Works was too subtle for most of the Jewish author’s contemporaries in London. Full comprehension could only occur posthumously. In this book Joseph Atwill introduces an entirely new alternative author and explains that the secrecy surrounding the authorship conspiracy was by design: “However, ‘Shakespeare’ intended that her satires remained largely unappreciated until after the collapse of Christianity that she no doubt hoped would occur shortly.”

Similar theories wore the patience of Shakespeare historian Samuel Schoenbaum threadbare. In his important work Shakespeare’s Lives, he waded through the swamp of “lunatic rubbish” that denies Shakespeare’s authorship, noting that its “sheer volume… appalls,” and is “matched only by its intrinsic worthlessness.” The “sheer volume“ of literature denying the authorship of William Shakespeare dwarfs the literature supporting his authorship. Does it matter that very famous people champion these worthless claims? The manic industriousness proceeds into its third century –absolutely certain of itself – without, as James Shapiro adds, “the discovery of a single document that confirms Oxford’s [or any other candidate’s] claim.” (Contested Will)

One major reason skeptics have had for doubting Shakespeare’s authorship since the early 19th century is the improbability of his story. This has led the “anti-Stratfordians” to dismiss him on the grounds that there is no evidence that the actor and owner of New Place in Stratford-upon-Avon wrote the plays and poems. The lack of evidence is thus construed as “evidence” that he did not write them. One of the most convincing arguments I have heard denying his authorship was a 2011 podcast by Bonner Miller Cutting, a trustee of the Shakespeare Fellowship. She has examined the last will and testament of “William Shagspere” along with 3,000 other Elizabethan and Jacobean wills and says that this specific will is “poorly composed,” a “disaster” and “a very significant piece of evidence that rules out this man as one and the same as the man who wrote the Shakespeare canon.”

Like Shakespeare, Eugene O’Neill was capable of “callous” behavior toward his wife. He married his third wife, Agnes Boulton, a successful writer of commercial fiction, in 1918. The years of their marriage—during which the couple lived in Bermuda and had two children, Shane and Oona—are described vividly in her 1958 memoir Part of a Long Story. O’Neill abandoned Boulton and their children for the actress Carlotta Monterey. Boulton often tried in vain to persuade her husband to stop drinking. Instead, she was periodically obliged to endure “some sudden and rather dreadful outbursts of violence, and others of bitter nastiness and malevolence [when] he appeared more like a madman than anything else.” On at least one occasion in front of many people, stinking drunk, O’Neill struck his wife violently in the face at a party given in his honor. This “mean-spirited” behavior came from the greatest playwright of the United States, and does not rule him out as the genius he was, any more than genius rules out bad character. Byron tormented Lady Byron and was the cause of his infant daughter Allegra’s death at four years of age, snatched from his mistress Claire, whom he tormented as well ( so much like Picasso’s demon!) He paid for his sins by enduring “the nightmare of my own delinquencies” (letter to his half-sister Augusta). Such self-ransacking evokes the Sonnets.

Over the years, Ludwig van Beethoven’s personal appearance degraded, as did his manners in public, especially when dining. He is remembered as being rude, “mean-spirited” and caring little how he dressed. Beethoven made a mess of his life, tormented his brother’s widow, snatched her only child away from her because of his power as patriarch, and, trying to raise the poor boy as his own, drove him to a distant hill with grazing sheep, where Beethoven's nephew put a bullet in his skull (he survived). If this aspect of his biography were one of the only details left to posterity, his authorship of the Ninth Symphony and all his other masterpieces might also have also been questioned.

The general argument of the “anti-Stratfordians” is expressed by Bonner Miller Cutting in the podcast mentioned above: “There are no trappings of culture anywhere to be found in the will of William Shagspere of Stratford-upon-Avon. There is nothing in this will that shows that this will-maker led a cultured life, or possessed a cultivated intellect.” Thus, we are told that it is improbable that William Shakespeare wrote the plays and poems. However, improbability is the major characteristic of Life itself having sprung from inorganic matter in one tiny and solitary corner of the universe. The irreconcilable controversy between those who believe Shakespeare wrote the Works attributed to him, and those who believe someone else did, will not die. Each side stubbornly persists in believing what they want to believe, and the truth remains indifferent behind all the conjecture. But the DoubtAboutWill website kindly includes this statement revealing the true author with finality:

Shakespeare lived apart from his wife, daughters and son for most of his adult life. His residence up to his retirement was for the most part London, the geographic center of his creativity. The absence of records revealing Shakespeare attending school in Stratford does not mean that he was unlettered, any more than the lack of school records mean that other important figures from Stratford who had successful careers (some at the university) left the town unlettered. It is considered odd that such a country bumpkin could have familiarity with aristocratic pastimes like hawking, hunting and tennis. As a traveling player in a theater company performing at aristocratic households in England, he frequently was able to witness aristocrats at play. He “visited royal palaces scores of times and was ideally placed to observe the ways of monarchs and courtiers.” (Contested Will) With such an unparalleled imagination, he need not be a nobleman to write about noblemen, nor travel to Italy to write about Italy. His plays are also populated with scoundrels, murderers, rapists, cheats, pimps, bawds, lunatics and cannibals. He need no more be an aristocrat to write about aristocrats, than to be a cannibal to write about cannibals.

Among all the candidates for authorship – whether the Earl of Oxford, Christopher Marlowe, Francis Bacon, or Mary Sidney – William Shakespeare himself is not even considered a candidate. His portrait in the 1623 First Folio by Martin Droeshout is a “strange engraving” to Joseph Atwill which has the “appearance of someone wearing a mask.” (See below for more on this portrait.) However, the vandalism done to this portrait that appears on the cover of his Shakespeare’s Secret Messiah removes all its original esthetic value and indeed can be called “strange.” This visual vandalism reflects the intellectual vandalism done to the plays and poems to support Atwill’s new theory.

Puns| Autobiography | The Droeshout engraving | Hidden in plain view

Improbability One of the many “interlineations” in the will – additions inserted between the lines – is the infamous “second best bed” left to his wife. Cutting assures us: “He really did mean to disparage his wife.” Shakespeare was unexplainably “callous” in not properly providing for her in the will, nor showing the most ordinary respect due a loved spouse: “It was considered ‘the decent thing’ for a man to provide for the maintenance of his wife in her widowhood.” Cutting sees the man who bequeathed the “second best

bed” to his widow as “mean-spirited,”

One of the many “interlineations” in the will – additions inserted between the lines – is the infamous “second best bed” left to his wife. Cutting assures us: “He really did mean to disparage his wife.” Shakespeare was unexplainably “callous” in not properly providing for her in the will, nor showing the most ordinary respect due a loved spouse: “It was considered ‘the decent thing’ for a man to provide for the maintenance of his wife in her widowhood.” Cutting sees the man who bequeathed the “second best

bed” to his widow as “mean-spirited,”  although this may not be enough to “rule out” William Shakespeare of Stratford as the author. We all have a tendancy to nourish wishful thinking when evoking the great masters whom we admire. A dashing nobleman, an “Errol Flynn type” like Edward de Vere, satisfies this wishful thinking more than a bald money-lender in Stratford who couldn’t even bequeath the “first best bed” to his widow.

although this may not be enough to “rule out” William Shakespeare of Stratford as the author. We all have a tendancy to nourish wishful thinking when evoking the great masters whom we admire. A dashing nobleman, an “Errol Flynn type” like Edward de Vere, satisfies this wishful thinking more than a bald money-lender in Stratford who couldn’t even bequeath the “first best bed” to his widow.

”There is no room for reasonable doubt that William Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon wrote (occasionally, as we are coming to realize, in collaboration with, principally, John Fletcher and Thomas Middleton) the works traditionally ascribed to him, and maybe one or two others.”

–Prof. Stanley Wells, CBE, Chairman of the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust

To balance my reading of Atwill’s “anti-Stratfordian” book, I was reading simultaneously Contested Will (2010) by the Shakespearian scholar James Shapiro, who (like Samuel Schoenbaum before him) carefully examines the ideas of the “anti-Stratfordians,” several of whom he calls “brilliant writers and thinkers who matter a great deal to me.” Despite their “venerable tradition of putting Shakespeare on trial,” he is not convinced that anyone other than William Shakespeare wrote (or in some instances co-authored) the Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies published in the First Folio in 1623 under his own name. There are thousands of books claiming that this is in fact the pen-name of one or several alternative authors, with no apparent connection to the glover’s son and actor. There are as well thousands of books claiming the authorship of this same glover’s son, who all agree was born and died in Stratford-upon-Avon. Whether “anti-Stratfordian “ or “Stratfordian,” they come forth like prosecution and defense attorneys in a courtroom, producing expert witnesses supporting their opposing viewpoints.

Despite the helter-skelter and confusion which prevails in this controversy, we all have one thing in common: we deeply admire the writer of the plays and poems. My purpose, like theirs, is to discover the truth about William Shakespeare. Shapiro writes of “the overwhelming evidence of co-authorship” which is present in “a surprising number of plays we call Shakespeare’s.” This practice was common in theater companies other than Shakespeare’s, as revealed in the Diary of Philip Henslowe, owner of the Rose Theatre in Elizabethan London. Henslowe records that two, three, four or more playwrights often worked together writing a play. Shapiro means that this fact encourages the idea that Shakespeare did not write any of the plays, since he evidently did not single-handedly write them all. And today he oscillates between scoundrel and god in the minds of people.

Both Joseph Atwill and James Shapiro focus on the deification of Shakespeare, but in completely different ways. Atwill’s previous book Caesar’s Messiah argues that Christianity was an invention of the Flavian caesars, and that Jesus is a fictional composite of several historical figures, among them the future Flavian emperor Titus, the “Son” of “God the father,” that is, the deified emperor Vespasian. (The younger brother Domitian became emperor at Titus’ death in 81 CE, and feeling left out, canonized himself as the third element in the trinity: the “Holy Spirit.”) Atwill writes that Titus’ destruction of Jerusalem in 70 CE was the “second coming” of Jesus fulfilling the prophecies of the New Testament in the exact time frame “predicted” (after the fact) by its writers. These were Jewish rebels taken captive in Jerusalem by the Romans and taken to Rome. Among them was Flavius Josephus (37 – c. 100), adopted by Titus and given the name Flavius, and whose The Jewish War and Antiquities of the Jews tell a similar story to the New Testament. The argument in Shakespeare’s Secret Messiah connecting the life and work of William Shakespeare with the hypothesis presented in Caesar’s Messiah is very strained.

Atwill believes that the author of the Works was Emilia Bassano, thought by A.L. Rowse to have been the “Dark Lady” of the Sonnets. Atwill believes that she created the deified Gentile “Shakespeare” as revenge on the Flavian caesars for having created the deified Jewish “Jesus” of the gospels 1,500 years before her: “And, just as Titus had fooled the Jews into worshipping ‘Jesus’, so Shakespeare would fool the Gentiles into worshipping ‘Shakespeare.’” Emilia’s project was so epically vast and complex, her hidden cipher story so filled with cryptic references to the New Testament and Josephus’ books, that it seems almost that she wrote the great plays and poems as an afterthought. Why a Jewish playwright out for revenge against Christianity would adorn Merchant of Venice with a universally scorned Jewish villain whose only redemption was conversion to Christianity, is not adequately explained by Atwill.

I began reading Shakespeare’s Secret Messiah prepared to give up my belief in William Shakespeare in the name of truth if Joseph Atwill indeed had discovered the ”real” author. After only a few pages I understood that he does not have a case – embarrassingly so. He relies so much on the arguments of preceding “anti-Stratfordians” that he offers no reasons of his own why Shakespeare did not write the plays and poems. His arguments promoting Emilia Bassano as author are confused and incoherent. The real purpose of his book is to continue with the thesis he presented in Caesar’s Messiah, with the New Testament, not Shakespeare’s Works, as the main focus. The vengeful animosity toward Christianity which he projects onto Emilia is in fact his own, perhaps reflecting his disappointments after years of Bible studies in a Jesuit seminary in Japan. The last part of the book deals with Suetonius’ Lives of the Caesars, the Book of Revelations and the Epistles of Paul (whose “epiphany” Atwill believes was a castration ordered by emperor Domitian, the “Holy Spirit”). After turning each new page I wondered: “What on earth does this have to do with Shakespeare?”

Atwill also writes that Emilia’s main sources for The Tempest were (yet again) the New Testament and the books of Josephus, in which there are “typological” narrations of shipwrecks. He ignores the contemporary source that most Shakespearean scholars agree upon: William Strachey (1572-1621), whose chronicles are among the principal works on the early English colonisation in North America. Strachey is best remembered for his eye-witness account of the 1609 shipwreck on the uninhabited island of Bermuda of the Sea Venture, caught in a hurricane while sailing to Virginia. After building two small ships during the ten months they spent on the island, the survivors were able to reach Virginia. Three characters in the play – Stephano, Caliban and Trinculo – are seen by Atwill as “a send up of the Flavian trinity,” Vespasian, Titus and Domitian (the Father, the Son and the Holy Ghost). The Tempest is believed to have been written around 1610-1611, when the Strachey’s chronicle was fresh in the minds of English readers. The connection with the shipwrecks of Josephus and Paul 1,500 years before the Sea Venture is again – very strained.

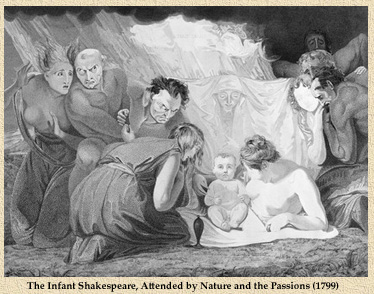

James Shapiro believes that the deification of William Shakespeare is the archetypal response to genius of simple-minded idolators like David Garrick (“the great Shakespeare’s priest” according to a contemporary) who organized the Stratford-upon-Avon “Jubilee” in 1769 – the point at which according to Shapiro Shakespeare “became a god.” Garrick, whose Ode hails Shakespeare as “Lord,” built a temple to Shakespeare on his estate on the bank of the Thames. Shapiro includes an illustration of this deification, a lithographic reproduction of George Romney’s painting The Infant Shakespeare, Attended by Nature and the Passions from around 1792. In this kitsch Nativity scene Baby Jesus is replaced by Baby Shakespeare.

James Shapiro believes that the deification of William Shakespeare is the archetypal response to genius of simple-minded idolators like David Garrick (“the great Shakespeare’s priest” according to a contemporary) who organized the Stratford-upon-Avon “Jubilee” in 1769 – the point at which according to Shapiro Shakespeare “became a god.” Garrick, whose Ode hails Shakespeare as “Lord,” built a temple to Shakespeare on his estate on the bank of the Thames. Shapiro includes an illustration of this deification, a lithographic reproduction of George Romney’s painting The Infant Shakespeare, Attended by Nature and the Passions from around 1792. In this kitsch Nativity scene Baby Jesus is replaced by Baby Shakespeare.

Today one can see a similar naïve and archetypal deification in popular idols like Elvis Presley and Marilyn Monroe. This popular deification of Shakespeare is at odds with Atwill’s theory that the deification was a conscious plan by Emilia Bassano to wreak vengeance on a Roman emperor who lived a millenium and a half before her. Shapiro writes: “The process that led to his deification was a curious one.” During his life, he was listed alongside “a score of other distinguished Elizabethan poets and dramatists,” as their equal. “It was only posthumously that Shakespeare was finally unyoked from the company of rivals or mortals.” Like Homer, Shakespeare became godlike.

Although she wrote poetry, I have not yet encountered research revealing that Emilia Bassano had the deep experience, instinct and knowledge needed to write, produce, direct and act in theatrical plays for a demanding public, while hiding a secret agenda that was not meant for this public, as Atwill claims in Shakespeare’s Secret Messiah. The requirements of writing and producing plays at this intense level for an entire professional life brings to mind Eugene O’Neill, who not only wrote, produced, directed and acted with his actor colleagues, but caroused with them after rehearsals, drank with them, joked with them, shared lovers with them. Can a fine aristocratic Elizabethan lady like Emilia Bassano, mistress of a baron who was the first cousin of Queen Elizabeth, possibly have caroused with this motley group of loud-mouthed Bohemians without contemporaries having noticed? It certainly would have been a scandal.

But a glover’s son from Stratford would have fit this ribald world like a glove. Despite the skepticism of the “anti-Stratfordians,” such lowly origins have often produced artistic geniuses. One of their candidates, Christopher Marlowe, was himself the son of a shoemaker. In fact, all the other successful playwrights of Shakespeare’s day were commoners. The masters of the Renaissance came from lower classes. Art offered these outcasts one of the few paths to take to ward off the poverty and neglect that otherwise awaited them as social pariahs. Mantegna was a peasant’s son, Uccello a butcher’s, Botticcelli a tanner’s. Cervantes’ father was a barber from Córdoba. Added to this list is the glover’s son Shakespeare.

In Italy such guilds were known as arti minori (minor guilds) and were held in low esteem. Sons from such lower class families in Italy had Art as one of the few ways out of a life destined for misery. Sons from well-respected families in the arti maggiori (major guilds) were almost never artists, for such a choice of career would bring disgrace on their families. Young Michelangelo had to defy the wishes of his family, enduring blows and punishment, for having dishonored the family by choosing the path of the artist. Artistic talent is inborn, a divine gift having nothing to do with social rank. One has done nothing to deserve it. One has made no effort whatsoever to acquire it. It can come to a glover’s son or to the son of fabulously wealthy lord, as was Michel de Montaigne.

Atwill links Emilia to the Elizabethan stage through the cousin of Queen Elizabeth, Henry Carey, 1st Baron Hunsdon, forty-five years older than Emilia, who was his mistress. Two years after their affair was over, Lord Hunsdon, Queen Elizabeth’s Lord Chamberlain, became a patron of Shakespeare’s theatre company, the Lord Chamberlain’s Men. When their affair came to an end, Emilia was 23, pregnant with Lord Hunsdon’s child, and (unhappily) married to her first cousin once removed, Alfonso Lanier, a Queen’s musician. The diary of Elizabethan astrologer Simon Forman suggests that Emilia told him about having several miscarriages. It is known that she gave birth to a son, Henry, in 1593 (presumably named after his father, Henry Carey) and a daughter, Odillya, in 1598. Odillya died when she was ten months old. The intense frenzy that the production of plays in Elizabethan playhouses required – the hiring and firing actors and stagehands, rehearsing, budgets and accounting, costume designs, scenography, writing scripts, producing, directing – does not seem like a burden that a young mother was able to shoulder, especially considering the social taboos of the day, and that her main contact with the theater world, Lord Hundson, left her two years before he had even started up Lord Chamberlain’s Men.

One woman known for certain to have been a playwright was the American, Delia Bacon, who wrote only one play. After an unsuccessful attempt to have it performed in New York in 1837, she became resolved that plays were meant to be read rather than performed. (One reader who thought her anonymously published play to have been “excellent” was Edgar Allan Poe.) Delia went on to publish a work proposing Francis Bacon as the real author of Shakespeare’s Works, and died two years later after a descent into insanity. (What influence her own name “Bacon” may have had in her choice of Francis Bacon as a candidate I do not know.)

One woman known for certain to have been a playwright was the American, Delia Bacon, who wrote only one play. After an unsuccessful attempt to have it performed in New York in 1837, she became resolved that plays were meant to be read rather than performed. (One reader who thought her anonymously published play to have been “excellent” was Edgar Allan Poe.) Delia went on to publish a work proposing Francis Bacon as the real author of Shakespeare’s Works, and died two years later after a descent into insanity. (What influence her own name “Bacon” may have had in her choice of Francis Bacon as a candidate I do not know.)

Delia’s “cipher” which was a key to unlocking the identity of the author evokes Atwill’s hidden “symbolic system” which for him unlocks the hidden identity of the author. Like Atwill, Delia believed that the Bard was “illiterate,” and like many “anti-Stratfordians,” she reveals almost hatred for “that booby” from Stratford, who clearly was a “stupid, illiterate, third-rate play-actor.” Delia said to Thomas Carlyle in England that questioning Shakespeare’s authorship is “a matter of knowledge.” This is the essence of the “anti-Stratfordians.” They are very often brilliant scholars who work from knowledge of the plays, poems and contemporary (at times contested) documents. The issue is what they do with this knowledge. Is it being used with Wisdom, or is it, as in the case of Delia Bacon, being misused by an unbalanced mind?

Emilia Bassano as well wrote plays primarily to be read by an “alert reader,” according to Joseph Atwill. Producing and performing plays for a demanding public is a nerve-wracking business. But writing plays comfortably at one’s writing table for potential readers is not quite as nerve-wracking and more suited to a highly educated aristocratic lady like Emilia. This presents another obstacle to Atwill’s theory: Shakespeare’s plays were written primarily for performance on stage – “within the girdle of these walls” (Henry V) – as the historical record makes quite clear. That they would also have a future audience of readers was a secondary purpose to their creation: “There is the playhouse now, there must you sit.”

The opening scene of Laurence Olivier´s production of Henry V presents actors backstage in the roles of actors preparing for the performance that soon is magically transfigured into the illusion of living people (actors) incarnating defunct people (historical and fictitious figures). Like a sculptor modeling clay Shakespeare moulded actors with whom he closely worked to create subtle works of art that were first and foremost intended to be audible to a theater public. The Prologue of Henry V emphasizes the fact that the play was to be heard by the theater-goer, asking “your humble patience pray,/ Gently to hear, kindly to judge, our play.” Like a musical score for a symphony, the words printed or written on paper were a blueprint for the theatrical spectacle intended for the ears of a public that never came into contact with the written texts, and who were for the most part illiterate.

This is the very essence of the plays: they were created to be performed on stage, listened to, viewed, and not read. Atwill misses this vital purpose of Drama when he writes: “In Hamlet there is a clue that the author of the verse is a woman who must speak her mind or the play will not get written – ‘the lady shall say her mind freely, or the blank verse shall halt for’t.’”(II:ii) Hamlet adresses Rosencrantz in this line, who has announced that the actors have arrived for rehearsal of the “play within a play.” That the blank verse might “halt” does not refer to the writing of the play Hamlet, but to the performance on the fictive stage of the “play within a play.” Atwill misreads this line because it better suits his agenda. Understanding that Hamlet is giving instructions on how each actor shall play his part does not suit his agenda. No actual woman is involved here. The male actor who will play the “lady” in Hamlet’s production is encouraged to speak the blank verse lines “freely.” This is not Emilia Bassano referring to herself in an autobiographical aside, as Atwill fantasizes.

For Atwill, as for the other “anti-Stratfordians,” the detailed knowledge of Italian culture embedded in the plays, especially that connected to Venice and Verona, makes it improbable that this “Shagspere” fellow from the Avon countryside could have possessed such intimate knowledge. Emilia Bassano was born in London of an English Protestant mother and perhaps never visited Italy. Her Italian immigrant father died when she was seven. Any knowledge she had about Italy must have come from her father’s family believed to have had origins in the city of Bassano near Venice, as well as books that this Shagspere fellow also had access to. But William Shakespeare may have had another source for his knowledge of Italy: dark-skinned Emilia herself.

There is no consensus as to the identity of the Dark Lady of the Sonnets, nor even that she was a real person. A.L. Rowse’s belief that the Dark Lady was Emilia Lanier (née Bassano) is dismissed by certain scholars. James Shapiro, for example, does not believe that the Sonnets are autobiographical. However, if Emilia indeed was Shakespeare’s mistress, then what an intimate source she would have been not only for information about Italy, but about Judaism as well. In this light, many of Atwill’s demonstrations of Emilia’s links to the plays – like references to the Bassano family and “Emilias” or Emelias” in them – can have as their explanation the possibility that Rowse was correct: Emilia was Shakespeare’s mistress. And Atwill’s belief that “literature always is, to some extent, autobiographical” can be explained as well by the possibility that these specific autobiographical details are Shakespeare’s references to his dark-skinned Jewish/Protestant/Italian mistress, and not Emilia’s references to herself.

Considering Atwill’s thesis – that the Works of Shakespeare were conceived as a Jewish female bard’s vengeance on emperor Titus and the Flavians 1,500 years before – he naturally focuses on the early co-authored play Titus Andronicus, considered one of the worst of the 37 plays – one bloody orgiastic pile of bodies, body parts, murder, torture, rape, cannibalism and psychopathic perversities. But for Atwill this play is the key to the “symbolic system” hidden in the entire opus, even in the quiet serenity of the Sonnets. The title of the play refers not to one historical figure, but is a combination of two historical figures: Titus Flavius, the Roman emperor, and Andronicus, cited in the Old Testament as a conqueror of Jerusalem (as was Titus) and usurper of the treasure stolen from its temple. Atwill’s entire interest in Shakespeare is centered in this play. The name “Titus” was a trumpet call for the author of Caesar’s Messiah, a name referring to Titus.

Like Delia Bacon before him, Atwill believes that other skeptics have not been looking in the right place to discover the true author of the plays, who was, of course, Francis Bac… I mean Emilia Bassano. Shapiro observes that Delia (like Atwill) was very protective of her new theory, seeing it as superior to those of other skeptics who “had just not read the plays with sufficent attention to obscure and seemingly irrelevant passages.” She (again like Atwill) devoted much energy “searching for each play’s deeper philosophical meaning,” that is, a “symbolic system.” Even though the non-Jew Marlowe could write the Jew of Malta, references to Judaism in Shakespeare’s plays prove to Atwill that the author was a Jewish woman who “applied the Hebrew dictum of an eye for an eye, or, in her words, ‘measure for measure.’” He conveniently ignores the fact that her mother, with whom she grew up, was Protestant, and that the one book of poetry that she published reveals a highly devout Christian.

In 1897 Samuel Butler wrote The Authoress of the Odyssey in which he, as Atwill does with Shakespeare, presents us with a female bard as the origin of Homer’s epic poem, a young Sicilian woman: “I conclude, therefore, that she was still very young, and unmarried. At any rate the [Odyssey] cannot have been written by Homer.” (Samuel Butler, The Authoress of the Odyssey, chapter entitled “The Whitewashing of Penelope.”) Like Butler, Atwill does not write “perhaps” or “it is very likely that…” but states with all-knowing certainty: ”She wrote plays in the blank verse style of prose that Marlowe had developed. [...] Her name was Emilia Bassano, and she wrote under the name ‘Shakespeare.’” I am not convinced. Shakespeare’s Works emanate something masculine, just as the works of Emily Dickinson emanate something feminine. Bassano’s only book of poetry, Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum (“the first fruits of a woman’s wit”) contains a prose preface which is a vindication of “virtuous women” against detractors of the sex, and strikes the reader as being very feminine: “A Womans writing of divinest things.”

On the other hand, Shakespeare’s Sonnets clearly reveal the speaker as being male. Atwill writes that although the poetry and prose of Salve Deus “seem to argue for women’s religious and social equality,” it was not Emilia’s primary purpose. Rather, ”it is likely she was taking a personal as well as a historical vengeance” after having endured humiliation for her dark skin, and seeing the Jews robbed of their Messiah by the Gentiles, that is, Titus and the succeeding centuries of Christians. Her title, Hail God, King of Jews, Atwill explains, was a way to defy the Christian hierarchy that condemned practicing Jews to death, by declaring in the faces of the aristocratic ladies to whom she dedicated her volume (including Queen Elizabeth) that God was King not of the Christians, but of the Jews. According to Atwill, this influence came from her Jewish father, who died when Emilia was seven. She lived with her Protestant mother after his death, and how much she was influenced by her, and whether or not she was a devout Christian as her poetry would suggest, is difficult to know. Atwill believes she was a “crypto-Jew” pretending to be “an overwrought believer in ‘Jesus’” while in truth detesting her mother’s religion.

Why would Emilia Bassano refer to herself as a women in Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum, and in the Sonnets as a man? Amantine-Lucile-Aurore Dupin is best known by her pseudonym George Sand, just as Mary Ann Evans is known by her pen name George Eliot. These male pseudonyms did little to hide the identities of the women using them. They were used by the authors to facilitate their careers during their lifetimes in a patriarchal society. After their deaths such secrecy was beside the point, and likely the female authors had nothing against being identified posthumously with their real names. For Emilia Bassano to have maintained this secrecy by design for four centuries implies a powerful control over the future, which may have been feasible for a powerful institution controlling millions of souls – like the Roman Empire – but much less so for a solitary woman at a great disadvantage in a male dominated Elizabethan society.

Scholarship is less helpful in this instance than instinct. Instinct is worth about two cents in the world of scholars, even though Darwin’s instinct preceded his theory of natural selection. Shapiro would no more value my poetic instinct that the Sonnets are autobiographical, than Atwill would value my instinct that a woman could not have imbued them with their obvious masculinity. The issue is not whether or not the Sonnets are autobiographical, but to what degree they are autobiographical. It is a matter of personal judgement for the reader to come to the understanding that a man must have written them. Both scholars approach their subject academically, since they are unable to do so artistically, which is not as irrelevant as it may seem considering that an artist is the subject of their respective research.

Atwill sees a “previously unrecognized symbolic system that stretches across all the works of Shakespeare and provides them with their deepest level of meaning.” In Caesar’s Messiah he had seen parallels or “typology” between the texts of the Old Testament and the New Testament, for example the similarities between the stories of Moses and Jesus, or the two Josephs who were captives in Egypt at different historical times. Atwill uses the same methodology to identify what he sees as a pattern that hides within the Works of Shakespeare. This methodology is even less convincing in Shakespeare’s Secret Messiah. The “symbolic system” linked to the Flavian dynasty is considered by Atwill to be the framework on which the entire opus was consciously constructed, which only a tiny few initiates – “alert readers” – can perceive.

There is a photo taken by a Mars probe in which certain people have seen a massive sculpted face like the stone images on Easter Island that lead them believe that they are the ruins of some alien civilization on Mars. Their minds see the pattern of a face when it is but one Martian mineral formation among others. In a similar manner Atwill sees the pattern of a “symbolic system” in the Works which means something else than it appears: “[A]t their deepest level the Works of Shakespeare were intended to inflict the same sense of humiliation on uncomprehending Gentiles that Titus intended for the Jews. […] For his complicity in the plot, ‘Shagspere’ was apparently paid part of the plays’ royalties, which enabled him to become a landowner in Stratford.” Exactly what form this complicity of “Shagspere” with Emilia Bassano assumed is not clarified.

This denial of Shakespeare’s authorship is part of a tradition centuries old. In Contested Will James Shapiro writes how the 18th-century scholar Edmond Malone, while exposing the outrageous Shakespeare forgeries of the teen-aged William Henry Ireland, also “helped institutionalize a methodology that would prove crucial to those who would subsequently deny Shakespeare’s authorship of the plays,” among whom would be Joseph Atwill almost 250 years later. Academically exposing the fraud of young Ireland (who was trying to please his father Samuel, engraver, collector and Shakespeare fan), Malone proceeded himself to create a fictional Shakespeare that fitted his personal vision. Shapiro believes that “the damage done by Malone was far greater and long-lasting” than that done by the notorious forger Ireland. The tradition had begun in which “writers projected onto a largely blank Shakespearian slate their own personalities and preoccupations.”

This denial of Shakespeare’s authorship is part of a tradition centuries old. In Contested Will James Shapiro writes how the 18th-century scholar Edmond Malone, while exposing the outrageous Shakespeare forgeries of the teen-aged William Henry Ireland, also “helped institutionalize a methodology that would prove crucial to those who would subsequently deny Shakespeare’s authorship of the plays,” among whom would be Joseph Atwill almost 250 years later. Academically exposing the fraud of young Ireland (who was trying to please his father Samuel, engraver, collector and Shakespeare fan), Malone proceeded himself to create a fictional Shakespeare that fitted his personal vision. Shapiro believes that “the damage done by Malone was far greater and long-lasting” than that done by the notorious forger Ireland. The tradition had begun in which “writers projected onto a largely blank Shakespearian slate their own personalities and preoccupations.”

This is exactly what Atwill has done, seeing a sequel to his hypothesis presented in Caesar’s Messiah in the mystery 1,500 years later surrounding the country boy and “upstart crow” who was simply too uneducated and common to have produced the Works. Two contemporary documents that Shapiro accepts as authentic– the birth and death certificates – Atwill claims were forged “as a part of the project” by Emilia’s conspirators: “They simply forged the documents that place his birthday and death on the feast day of England’s patron Saint.” As in the greater part of Atwill’s conjectures, he offers no evidence, ignoring centuries of thorough examinations by Shakespearean scholars who have weeded out the forgeries from the authentic documents.

Nor does Atwill reveal why he is certain that Emilia Bassano is involved in the editing of the 46th Psalm of the King James Bible (published in 1610 when Shakespeare turned 46), in which the 46th word from the beginning is “shake” and the 46th word from the end is “spear.” Shapiro, commenting on John Thomas Looney, inventor of the most popular authorship theory even today, writes that the latter created “a portrait of the artist concocted largely of fantasy and projection, one wildly at odds with the facts of Edward de Vere’s life.” Replacing “Edward de Vere” (Earl of Oxford) with “Emilia Bassano,” the reader is given, in a nutshell, the essence of Shakespeare’s Secret Messiah.

John Thomas Looney’s “Shakespeare” Identified from 1920 is called by Shapiro “the most compelling book on the authorship controversy to have appeared, and in this respect it has yet to be surpassed.” He adds that there are indeed facts that make Oxford’s candidacy seem logical: “He had been praised in his lifetime as both poet and playwright, and his verse was widely anthologized.” But the greatest obstacle for Looney and the Oxfordians to overcome was how he wrote at least 12 of Shakespeare’s plays after his death in 1604. By fantastic speculations, misreading and intellectual dishonesty, they “could refute almost any counterclaim.” But even among the Oxfordians there is an irreconcilable division concerning the claim that Edward de Vere was Queen Elizabeth's secret lover and their illegitimate son was the Earl of Southampton.

The epic lengths to which various skeptics went trying to prove the authorship of various “candidates” is truly astonishing – all for naught. One 19th-century skeptic published a book in which he enlightens the world to the cryptic last page of The Tempest with, reading the first letter of each key word from the bottom up, this secretly encoded signature: FRANCISCO BACONO. Another 19th-century skeptic invented a great cipher wheel to decode the entire Works of Shakespeare to prove with absolute certainty that Francis Bacon was not only the author, but the bastard child of the Earl of Leicester and Queen Elizabeth – the rightful heir to the British throne! He was so certain that he had found the cryptic message from Francis Bacon to posterity revealing the exact location of the lost manuscripts of the plays and poems, that he sailed for England to oversee the last phase of his epic project. Once there, Shapiro writes that he rented dredging machinery “to search the bottom of the Severn River for the buried manuscrips, sealed in water-proof lead containers.” It was international news.

The epic lengths to which various skeptics went trying to prove the authorship of various “candidates” is truly astonishing – all for naught. One 19th-century skeptic published a book in which he enlightens the world to the cryptic last page of The Tempest with, reading the first letter of each key word from the bottom up, this secretly encoded signature: FRANCISCO BACONO. Another 19th-century skeptic invented a great cipher wheel to decode the entire Works of Shakespeare to prove with absolute certainty that Francis Bacon was not only the author, but the bastard child of the Earl of Leicester and Queen Elizabeth – the rightful heir to the British throne! He was so certain that he had found the cryptic message from Francis Bacon to posterity revealing the exact location of the lost manuscripts of the plays and poems, that he sailed for England to oversee the last phase of his epic project. Once there, Shapiro writes that he rented dredging machinery “to search the bottom of the Severn River for the buried manuscrips, sealed in water-proof lead containers.” It was international news.

In 1888 Ignatius Donnelly, a former congressman and lieutanant governor of Minnesota, wrote The Great Cryptogram: Bacon’s Cipher in the So-Called Shakespeare Plays. After six years of exhausting labor, he published it at the publishing house established by Mark Twain, a renowned “anti-Stratfordian.” Joseph Atwill as well has devoted years of epic labor researching his own “great cryptogram,” or as he calls it, a “symbolic system.” Donnelly was absolutely certain of his theory, confident “beyond a doubt” that “there is a Cipher in the so-called Shakespeare Plays. The proofs are cumulative. I have shown a thousand of them.” Equally as confident, Atwill proudly emphasizes for posterity that he alone is the origin of this newest authorship theory: “I discovered both that Emilia was the author and that the plays were reversals of the Flavians’ typology.”

In a similar vein, Katherine Chiljan writes in Shakespeare Suppressed (2011) that the “Stratford Man” and her candidate “merged into one identity after both of their deaths, and it was no accident, as this book will explain.” (Uh oh, sounds like a conspiracy!) This is exactly the position of Delia Bacon, and each of the advocates of the 86 candidates that have been put forth so far. With the same certainty that fueled Delia Bacon’s belief in Francis Bacon (and evoking Delia’s eagerness), Chiljan writes: “I am certain, ‘as certain as I know the sun is fire’ (Coriolanus, 5.4.49), that Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford (1550-1604), is the nobleman in question behind the pen name, ‘William Shakespeare.’”

Chiljan adds: “All documentary evidence gathered about the Stratford Man reveals a successful businessman and property owner with ties to the theater, but that is all.” That is all? That is everything in a nutshell! “Ties to the theater” are exactly what James Shapiro has described in detail in Contested Will: the buying of playhouses, attending shareholder meetings, writing, staging, casting, directing and acting in Hamlet, The Tempest and so on by William Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon. The reason that a large number of secret conspirators, using half a dozen different and randomly spelled names on the published works – each of them a separate “pen name” – would orchestrate an epic hoax in which Ben Jonson would forever be remembered in posterity as a liar for naming his friend Shakespeare as the author of the First Folio, is explained by Chiljan:

The great author did not claim authorship during his lifetime because he was a nobleman. Generally speaking, those of high rank who wrote poetry or drama did not seek publication or compensation for what they wrote. After their death, however, the stigma of print would disappear, and their friends or descendants could openly publish their work with their names. But for some reason – some very important and unusual reason – this courtesy was not extended to the great author.

Something went terribly wrong, apparently. Oxford was supposed to be identified immediately after his death. “But for some reason” this Shagspere guy got all the credit! The person whose portrait and name were on the title page of the First Folio had incredible, undeserved luck. He got all the glory and didn’t have to do a lick of work, as Chiljan elucidates: “The Shakespeare authorship was ‘given’ to him after his death.” Oxford died in 1604, that is, before about 12 plays ascribed to Shakespeare were written.

And so Delia Bacon’s lunacy continues into each new generation. Contrary to Chiljan’s statement above (which was supposedly the reason for the conspiracy), noblemen such as Edward De Vere did indeed publish without fear of breaking convention. A pseudonym was unnecessary. Eight poems by Oxford were published in The Paradise of Dainty Devises (1576) under his own name. Considering that there was no taboo for a nobleman to publish under his own name, why on earth would Oxford publish eight minor poems in an anthology openly under his own name, and on the greatest literary opus of the English language be too modest to reveal his authorship, and hide it behind a pseudonym and an engraving of the glover’s son? As Shapiro writes, it all seems “awfully far-fetched.”

Before producing candidates for authorship, “anti-Stratfordians” are obliged to provide evidence that William Shakespeare from Stratford cannot be among them. Referring to the tiny few authentic documents from the time which reveal him as being a money-lender and shrewd businessman, Shapiro writes that “an unbearable tension had developed between Shakespeare the poet and Shakespeare the businessman.” This tension between the image of a gentleman poet in London and a shrewd businesman in Stratford led to the conjecture “that we were dealing with not one man, but two.” But Shapiro does not assume that the poet speaks in his own person in the Sonnets: “We have no idea to what extent Shakespeare is writing out of his own experience [in the Sonnets] or simply imagining a situation involving two fictional characters.” However, in Sonnet 136, it is difficult to see that the author and the speaker in the following lines are anything else than one and the same person:

Atwill is misreading both Emilia Bassano’s pun on “Will” in Salve Deus and William Shakespeare’s pun on “Will” in the Sonnets. If A.L. Rowse in fact was correct, and Emilia was Shakespeare’s mistress, then perhaps her puns on “Will” referred, not to an abstract literary symbol “Divine Will” ( Rex Judaeorum – King of the Jews) replacing the symbol “Jesus” as Atwill believes, but very simply to a living man – her lover. Being well-educated and a highly gifted poet, she in such case would not have been blind to the exraordinary genius – “Divine Will” – who shared her bed. And when the writer of the Sonnets asks “Make but my name thy love,” he reminds the woman whom he thinks does not love him to remember: “my name is Will.”

In Elizabethan England “will” could also mean sexual desire and slang for male and female sexual organs. Will also means a testament left after a person dies. Despite the differences of styles and genders in Salve Deus and the Sonnets, the speakers in each use double and triple entendres with the proper name, the noun and the verb “will.” Atwill writes of “the correct grammar” in capitalizing the “w” in the name Will, and not doing so with the noun meaning intent. But it need not be so in Elizabethan English, where nouns were sometimes capitalized, sometimes not, a trait of the parent of English – German – in which all nouns are capitalized. In the passages of Salve Deus quoted by Atwill, other nouns are also capitalized: “Friends”; “Grace”; “Displeasure”; “Flesh”; etc. Given this grammatical ambiguity, the reader of Salve Deus and the Sonnets can never be certain if the capitalized “Will” refers to the proper name or the noun or the verb, nor grasp all the veiled meanings as in these lines from Sonnet 135:

But the number one reason for the pun, its veritable punch-line – that the writer of the Sonnets is named Will – is rendered totally meaningless if the writer is named Emilia, Francis, Edward or other names of candidates. Such punning was common in Elizabethan England. In John Donne’s poem A Hymn to God the Father one sees a similar use of a pun on the writer’s name, not as a pseudonym, but as his own name given him at birth:

Listening to the pure sounds of the words, the reader hears both “when thou hast done” and “when thou hast Donne.” And likewise he hears both “For I have more” and “For I have More.” That is, when God has Donne (he was ordained into the Church of England) he does not have Donne, because the erotic love for his wife Ann More (with whom he had twelve children) distracted him from the divine love of God. These puns conceal the poet’s erotic love for a woman. In Shakespeare’s Secret Messiah we learn that “the ‘Will’ in Salve Deus, like the ‘Will’ described in the sonnets, is to be seen as Titus’s replacement. Emilia borrowed this intertextual technique from the authors of the Gospels and Wars of the Jews whose comic system spanned a number of books.” This information can only be perceived and understood by “alert readers.”

However, Atwill’s knowledge of Shakespeare and his world clearly does not reach the scope and depth of Shapiro’s. Among the overwhelming pieces of evidence that Shapiro presents clearly identifying the Stratford man as the playwright and poet, is the homage of fellow playwright Thomas Heywood (1570?-1641), who “had his hand in over two hundred plays over the course of a long career.” Heywood clearly uses the pun “Will” in association with his contemporary William Shakespeare:

The Dark Lady sonnets begin with 127 and mark a change of tone from that of serene musing on a love, to a disturbed passion which is at times close to frenzy. The opening sonnet introduces his mistress as “black”, but then digresses into a tirade against cosmetics and face painting, something which the writer did not find easy to tolerate, for he seems to equate it with a falseness in human relations. The sexual attraction of white males to dark-skinned beauties is archetypal behavior that occurs throughout history. Perhaps the most renowned example of this after Shakespeare’s Dark Lady is the black mistress of Charles Baudelaire.

Jeanne Duval was a Haitian-born actress and dancer of mixed French and African ancestry. For 20 years, she was the mistress of Baudelaire. They met in 1842, when Duval left Haiti for France, and the two remained together, albeit stormily, for the next two decades. Duval is said to have been the woman whom Baudelaire loved most after his mother. She was born in Haiti on an unknown date, sometime around 1820. Poems of Baudelaire’s which are dedicated to Duval or pay her homage are: “Le balcon,” “Parfum exotique,” “La chevelure,” “Sed non satiata,” “Le serpent qui danse,” and “Une charogne.” Baudelaire called her “mistress of mistresses” and his “Vénus Noire” (“Black Venus”).

The Dark Lady sonnets and Baudelaire’s poems inspired by his black mistress are at times very erotic. Atwill’s interpretation of the Sonnets replaces this eroticism with a very cold and calculating plan to counterfeit male sexuality throughout the opus and proceed with a very thought-out, unemotional “symbolic system” intended to be vengeance on a Roman emperor who lived 1,500 years before the female bard. Why would the Englishwoman and writer of the plays and poems have a greater need for revenge on Titus than on Henry VIII, this great and evil enemy of womankind and father of the queen?

There being no “cradle-to-grave life of Shakespeare,” seeking an identity of the writer in the works (as is so congenial to do with Montaigne) is seen as foolhardy by Shapiro. But even the plays can contain bits and pieces of autobiographical detail as in the following lines in Troilus and Cressida:

Any poet would naturally want to leave behind poetry that reflects his or her true gender. Atwill believes that the poet Emilia Bassano wrote one slender collection of poetry published under her own name and gender, and wrote as well the greatest written opus in the English language, publishing it under a pseudonym at enormous cost, pretending to be a man, counterfeiting male desires and passions throughout the opus, and willingly denying herself the great satisfaction granted writers who publish under their own names – in order to bequeath a secret “symbolic system” to readers of the future, which was the main purpose of her opus.

Shapiro quotes from Johnson’s biography of James Thomson to illustrate that admirable things the poet wrote about himself proved to be the empty boasting of a bald-faced liar. Thus it seems that Shapiro assumes that all poets are bald-faced liars. (In fact, Shakespeare himself may have believed this judging from the exchange in Timon of Athens where the philosopher accuses the poet of being a liar.) How truthful was Samuel Johnson himself? Did he as well invent fictional poets? How could he possibly have the intimate knowledge that Alexander Pope was “insensible” to Music which he celebrates in his poetry? Somewhere mixed in with the spectrum of bald-faced lies, distortions, exaggerations, wishful thinking and honest self-appraisal, a poet is leaving a trace of who he or she was, an identity.

Shapiro seems to deny the possibility of bonafide autobiography in the Sonnets, in which he sees the “utterances of fictive speakers of Shakespeare’s poems” who apparently give vent to fake emotions. He mocks the claim of David Masson in 1856 that the Sonnets are “a poetical record of his own feelings.” Why would any poet worth his salt falsify such emotions, as Atwill implies that Emilia had done? What is the point of poetry if not knowing oneself? To dismiss autobiography in Shakespeare’s Works – especially the Sonnets – is as risky as reading detailed facts of his daily life in them as did Malone. In the first case, it is not enough, and in the second, too much.

Shapiro has no problem dismissing the belief of other great poets that Shakespeare indeed was the speaker of the Sonnets, baring his soul, speaking of very real joys, regrets and sorrows. That “romantic” Wordsworth firmly believed Shakespeare “unlocked his heart” in the Sonnets is ridiculed by Shapiro, even as he admits that the former’s poem The Prelude was “autobiographical.” Needleess to say, autobiographical poetry did not begin with Wordsworth. The Roman poet Propertius (c. 50 BC - 15 BC), for example, wrote four books of elegies, totaling around 92 poems. Propertius’ work is dominated by the figure of a single woman, one to whom he refers throughout his poetry as Cynthia. She is named in over half the elegies of the first book and appears indirectly in several others, directly from the first word of the first poem in the Monobiblos:

Shapiro is as tenacious as an Oxfordian concerning the absence of autobiography in the Sonnets, a literary genre which was according to him ”extremely unusual” in Shakespeare’s time. The Sonnets are “fiction,” apparently even this line: “My name is Will.” If he would agree that this single line is in fact autobiographical, then how many more such lines are there in this work of “fiction”? Contradicting himself, Shapiro cites one researcher who discovered “a dozen or so” Tudor writers who did indeed “incorporate their lives into […] courtly and popular verse.” Again contradicting himself, he admits the possibility that even Shakespeare drew on his personal experience in his poems and plays: “I don’t doubt that he did.” But he believes that “these experiences can no longer be recovered.”

Thus, when a reader experiences, grief, regret, doubt, joy and other emotions in these poems, they can’t be identified as a reflection of the writer’s mood at the exact moment of writing, which according to Shapiro “can no longer be recovered.” These pure emotions must be regarded as “fiction.” We are no longer in the realm of the academic scholar, just as the glover’s son was not from this realm. We are in the realm of the alert listener of musical tones and nuances as in Bach’s Art of the Fugue, a musical counterpart to the Sonnets. As in the line “My name is Will,” Bach as well was autobiographical in the last of these fugues, with a theme based on the notes making up his name: B (B-flat) A C H (B-natural). He died leaving it unfinished.

To make his point that the Sonnets should not be considered autobiographical, Shapiro relates how he was in the audience at London’s Globe Theatre to hear a renowned Oxfordian speak in 2008. The speaker enlightened the audience that the Fair Youth of the Sonnets was Oxford’s son by Queen Elizabeth, that is, rightful heir to the British throne. The Fair Youth, a friend of Essex, was imprisoned after the rebellion instigated by the latter, and Oxford pleaded as a lawyer for his son in certain sonnets. Shapiro found it all “demoralizing” and condemned the speaker’s “construing fiction as autobiographical fact.” However ridiculous the above fairy tale may be, Shapiro has no way to dismisss the Sonnets as “fiction,” since he obviously is not privy to the innermost thoughts of Shakespeare at the precise moments when he wrote down each of them. Not even the most obsessed Shakespearian researcher can ever document the origin of these moments. Instinct, not academic research, tells us – as it did Wordsworth – that the poet “unlocked his heart” in these poems.

Shapiro argues that the lives of Elizabethan and Jacobean people did not resemble our own, and that we project our modern selves onto our perception of their times. I agree, but such essences as grief, love, doubt, joy and regret found in the Sonnets are as old as humanity. The splendid ancient image of Odysseus’ dog recognizing his master after twenty years’ absence, waggging his tail and dropping dead from joy, is universal and still recognizable after 3,000 years to anyone who has loved a pet dog. This subtle degree of nuance in the Sonnets is not fiction. Not even a master like Shakespeare could invent such emotions. They come directly from life.

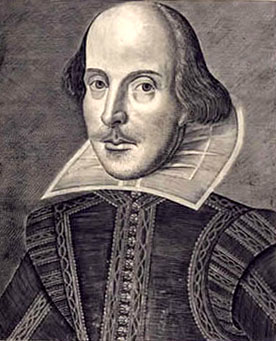

The Martin Droeshout portrait of Shakespeare has been vilified over centuries as “strange,” “oafish,” “unflattering,” “abominable” and even “constipated.” As in Atwill’s appraisal, it is seen as a “mask” hiding a more worthy candidate than this ridiculous Shagspere fellow in Stratford hoarding malt and tending his father’s dungheap. Whatever esthetic qualities it may have, they certainly do not provide an intelligent argument against Shakespeare’s authorship, especially considering Ben Jonson’s testimony that it is indeed a likeness of the poet.

The Martin Droeshout portrait of Shakespeare has been vilified over centuries as “strange,” “oafish,” “unflattering,” “abominable” and even “constipated.” As in Atwill’s appraisal, it is seen as a “mask” hiding a more worthy candidate than this ridiculous Shagspere fellow in Stratford hoarding malt and tending his father’s dungheap. Whatever esthetic qualities it may have, they certainly do not provide an intelligent argument against Shakespeare’s authorship, especially considering Ben Jonson’s testimony that it is indeed a likeness of the poet.

Martin Droeshout (1601-1651) came from a Flemish family of painters and engravers. He was twenty-two years old when the First Folio was published, and despite his detractors, possessed exceptional artistic talent. It is not known if Droeshout, who was only fifteen when Shakespeare died, ever met the poet. Some have surmised that he had been provided with an original picture of some sort on which the engraving was based. Another possibility is that he met Shakespeare, and made a preliminary sketch. Ben Jonson, John Hemminge and Henry Condell, who were involved in the publication of the First Folio, all knew William Shakespeare personally and possibly provided the engraver with a description or an existing likeness. The brothers, actors and shareholders in the theatre company, Richard and James Burbage, referred to Shakespeare as “the man they all knew” in a letter to the Earl of Pembroke. The playwright was well-known in his lifetime.

Martin Droeshout made engravings of several important people: John Donne, the Duke of Buckingham, the Bishop of Durham, the Marquis of Hamilton and Lord Coventry. He seems to have had an excellent reputation as a master engraver since he was commissioned in 1631 with the second edition of Crooke’s “Mikrokosmographia,” a massive folio containing over 1,000 pages. The Droeshout engraving is the only image of Shakespeare to have been vouched for by a contemporary. It is considered to be the most authentic image of Shakespeare. The search for the “template” to this portrait has been going on for 400 years and has inspired many forgeries. The only other likeness that is universally agreed upon is the bust over his tomb in Stratford-upon-Avon, some twenty years older than the face in the engraving.

“Anti-Stratfordian” Katherine Chiljan has called the Droeshout portrait a “gentleman monster” and implies that Droeshout intentionally engraved an oafish image that was meant to be ambiguous, a “mask” hiding the “real” author, Edwarde de Vere. Droeshout as well was seemingly part of the conspiracy to hide the greatest poet of the English language behind the face of an oafish money-lender in need of a shave. The English painter Thomas Gainsborough (1727-1788) also judged the portrait harshly: “I never saw a stupider face. It is impossible that such a mind and such a rare talent should shine with such a face and such a pair of eyes.” The face of the very “booby” that so offended Delia Bacon (before she went mad). Critics complain that the head is too big, the eyes uneven, crudely proportioned clothes, non-anatomical line from ear to chin suggesting a mask, etc. Dare I say I kind of like its Picassoesque charm?

They overlook that the engraving reveals highly-skilled, detailed and painstaking work with the engraving needle, the work of a master who was commissioned for many other important portraits. But, they argue, there is no laurel wreath around his head, as in the title page portrait from Ben Jonson’s folio of 1616 (left). All the fuss about Droeshout’s supposedly clumsy engraving is contrasted with Robert Vaughan’s portrait of Jonson, which is hardly superior esthetically speaking. “Looke not on his picture,” wrote Ben Jonson in his elegy to Shakespeare in the 1623 Folio, “but on his Booke.” This statement has been misread by generations of “anti-Stratfordians” as being cryptically mysterious, as if he is saying “Don’t look at this face, it is not the Bard’s,” when the meaning is quite unambiguous and clear. Four lines before, Jonson directly referred to Droeshout’s engraving: “O, could he but haue drawne his wit.” Since the artist was unable to draw the Bard’s wit, the reader is directed to “his Booke,” where his wit reigns. Not mysterious at all. But the conspiracies are so complex, numerous and goofy that one essay in Scientific American, April 1995, even suggested that the Droeshout engraving actually portrays Queen Elizabeth, who of course wrote the plays and poems attributed to this Shexpere fellow. Samuel Schoenbaum wrote that

They overlook that the engraving reveals highly-skilled, detailed and painstaking work with the engraving needle, the work of a master who was commissioned for many other important portraits. But, they argue, there is no laurel wreath around his head, as in the title page portrait from Ben Jonson’s folio of 1616 (left). All the fuss about Droeshout’s supposedly clumsy engraving is contrasted with Robert Vaughan’s portrait of Jonson, which is hardly superior esthetically speaking. “Looke not on his picture,” wrote Ben Jonson in his elegy to Shakespeare in the 1623 Folio, “but on his Booke.” This statement has been misread by generations of “anti-Stratfordians” as being cryptically mysterious, as if he is saying “Don’t look at this face, it is not the Bard’s,” when the meaning is quite unambiguous and clear. Four lines before, Jonson directly referred to Droeshout’s engraving: “O, could he but haue drawne his wit.” Since the artist was unable to draw the Bard’s wit, the reader is directed to “his Booke,” where his wit reigns. Not mysterious at all. But the conspiracies are so complex, numerous and goofy that one essay in Scientific American, April 1995, even suggested that the Droeshout engraving actually portrays Queen Elizabeth, who of course wrote the plays and poems attributed to this Shexpere fellow. Samuel Schoenbaum wrote that

the engraving was commissioned and approved by the compilers of the First Folio, John Hemmings and Henry Condell, both members of the King's Players, Shakespeare's acting company. The testimony or involvement of these three men is our best evidence for the print's value as a portrait. Despite the stiff and oddly-porportioned garments, the evidence points to the authenticity of this likeness of England's most celebrated playwright.

S. Schoenbaum, William Shakespeare, a Documentary Life (Oxford University Press, 1975)

The argument seems to be that William Shakespeare from Stratford was simply not handsome enough to have written the plays and poems.

The preface to the First Folio was signed by fellow actors John Heminge and Henry Condell, “who had worked alongside Shakespeare for over twenty years”(Shapiro). Giving no source Atwill claims that “most scholars” believe Ben Jonson in fact wrote the preface attributed to these men. But why a prominent and respected playwright like Ben Jonson would display himself as a fraud and liar to all posterity with his poem “To the Memory of My Beloved Master William Shakespeare, and What He Hath Left Us” (signed under Jonson’s own name and plainly identifying the man of Stratford), is not made clear by Atwill. He claims that Jonson was “a member of Emilia Bassano’s inner circle” fully aware of her secret authorship of the Works and their “symbolic system,” which he nonetheless deceitfully ascribed to “My Beloved Master William Shakespeare.” Jonson’s poem eulogizing his friend from Stratford begins:

Jonathan Star has gone very deep like Joseph Atwill examining the Works of Shakespeare in minute scholarly detail, to come up with another female candidate: Mary Sidney Herbert, the Countess of Pembroke. Like Atwill arguing for Emilia Bassano, Star sees very much evidence in the plays and poems that convince him with absolute certainty that Mary Sidney was the author. I remind the reader of James Shapiro’s observation above, how in the 18th century Malone “helped institutionalize a methodology that would prove crucial to those who would subsequently deny Shakespeare’s authorship of the plays.” Using this methodology in a similar manner as Atwill, and with the same scholarly attention to detail, Jonathan Star analyzes the above lines by Ben Jonson to “prove” that Mary Sidney wrote under the pen-name “Shakespeare,” and rewrites Jonson’s lines to better suit his agenda, interpreting them in the following manner:

Jonathan Star has gone very deep like Joseph Atwill examining the Works of Shakespeare in minute scholarly detail, to come up with another female candidate: Mary Sidney Herbert, the Countess of Pembroke. Like Atwill arguing for Emilia Bassano, Star sees very much evidence in the plays and poems that convince him with absolute certainty that Mary Sidney was the author. I remind the reader of James Shapiro’s observation above, how in the 18th century Malone “helped institutionalize a methodology that would prove crucial to those who would subsequently deny Shakespeare’s authorship of the plays.” Using this methodology in a similar manner as Atwill, and with the same scholarly attention to detail, Jonathan Star analyzes the above lines by Ben Jonson to “prove” that Mary Sidney wrote under the pen-name “Shakespeare,” and rewrites Jonson’s lines to better suit his agenda, interpreting them in the following manner:

Thus, I [Ben Jonson] am not able to openly name you [Mary Sidney], nor address this eulogy to you directly (as I would have wished), nor am I able to write anything about you by which you could be positively identified as the Author; all my praise must be in the form of oblique references to what others have written about you and the things by which you are already known.

Atwill has a very similar, almost identical argument, but being of a different “inner circle,” Ben Jonson of course is cryptically referring to Emilia Bassano in the elegy, not Mary Sidney. Using bold-face fonts to highlight portions of the text that conceal a “secret messsage” in the exact way Atwill does, totally certain of himself like the other “anti-Stratfordians,” Star informs us that we need not look anywhere else than Mary Sidney to solve the question of authorship. Meanwhile, to add to the confusion, Katherine Chiljan knows “as certain as I know the sun is fire” that Edward de Vere is the mysterious person cryptically referred to by Jonson in the elegy when he honors his “beloved master” whom he identifies as William Shakespeare. In his collected work, Jonson lists William Shakespeare as one of eight “principal comedians” and again as one of eight “principal tragedians.” This can not be Edward de Vere. Thus, we have three “anti-Stratfordians” and three positively identified playwrights, with each skeptic as certain as “the sun is fire” that they are correct beyond all doubt.

After his careful evaluations of the two main candidates for authorship – Bacon and Oxford – and the misguided literature that they inspired, James Shapiro is merciless in his demonstration that no one other than William Shakespeare from Stratford-upon-Avon wrote the plays and poems. Had he read Shakespeare’s Secret Messiah, which was published three years after his Contested Will, he undoubtedly would have been as merciless on Joseph Atwill as he was on Delia Bacon. It is possible that Atwill, like Delia Bacon, will live out the rest of his life ignoring the evidence hidden in plain view revealing Shakespeare as the author, and continue with his theory that the “crypto-Jew” Emilia Bassano – in her spare time from being a mother, mistress, wife and writing the very lengthy Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum under her own name – wrote the Works under the pen name “William Shakespeare” in order to secretly and cryptically exact vengeance on emperor Titus, the Flavian dynasty, and fifteen centuries of Christendom that followed them, the whole to be deciphered long after her death by “alert readers.”

In the same vein, Katherine Chiljan, in Shakespeare Suppressed, also believes in a secret and cryptically orchestrated conspiracy that places, not Emilia Bassano, but Edward de Vere behind the “mask” that Martin Droeshout – apparently part of the conspiracy – designed. Chiljan mocks the “Shakespeare professor” like James Shapiro who is so terribly deluded to believe, as Ben Jonson openly declared, that William Shakespeare wrote the Works attributed to him. She asks: “But does the professor look at the historical record? Apparently, he does not. If he did, he would see how obvious it is that his man, the Stratford Man, was not the great author, Shakespeare.” Whatever criticism she may have against the arguments presented by James Shapiro, her claim that he “apparently” did not “look at the historical record” cannnot be taken seriously.

In the next to the last part of Contested Will Shapiro confronts the arguments of “anti-Stratfordians” and their most popular candidate at this moment in history: Edward de Vere. Those of Chiljan’s colleagues who have signed “The Declaration of Reasonable Doubt” have in turn been provided with enough reasonable doubt by Shapiro to purge themselves and give homage to him who rightly deserves it. But the controversy will apparently never end. On the DoubtAboutWill website with its “Declaration of Reasonable Doubt,” an unnamed writer has severely criticized Contested Will and concludes that Shapiro “presented evidence that he thinks makes a convincing case for his man, but which we don’t.” Like Ignatius Donnelly before them, confident “beyond a doubt” that Francis Bacon Bacon wrote the plays and poems, Katherine Chiljan and her colleagues have no doubt that Edward de Vere wrote them.

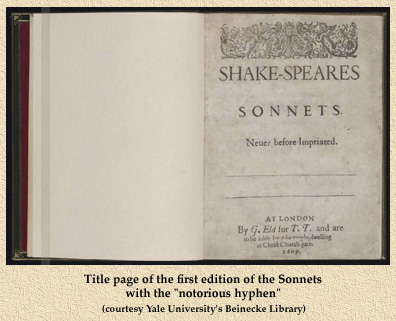

And so it will continue to be – both sides in this controversy ending their detailed cases against the other with the purely subjective observation: “we don’t believe they make a convincing case.” For Shapiro’s adversary quoted above, he is the “high priest of Stratfordian orthodoxy. That’s why he thinks what he thinks.” While mocking Shapiro in this manner, the same writer, however has no problem giving full support to Chiljan, the high priestess of Oxfordian orthodoxy. Considering Joseph Atwill’s most recent delirious fantasy about who wrote the plays and poems, I am inclined to believe in Shapiro, despite minor errors that have been pointed out in his book. (An example: Shapiro erred stating just where the “notorious hyphen” in “Shake-speare” first appeared in print.) Shapiro’s judgement that the fog of time has clouded the perception of the “anti-Stratfordians” explains why there is not one, but at least 86 hypothetical Shakespeare authorship candidates in their exclusive club.