In the compartmentalized bunkers of universities Art is referred to as one discipline among others, ranked equally with philosophy, science, mathematics and theology. This is an error. Art is not the sibling of the above disciplines, but their mother. This eternal misunderstanding automatically makes the artist an outsider, as history shows him to be. Through Art – the most ancient manifestation of human knowledge – all other knowledge was born. These very same alphabetical signs on this page are the vehicles of our knowledge, twenty-six drawings that have evolved from the most distant depths of paleolithic times. This modern alphabet is still linked to the mystery 30,000 years ago when what were believed to be humanity's earliest known drawings were scratched into a bone by an artistic hand to record the phases of the moon. The modern discipline called archaeoastronomy has established that the earliest evidence of an astronomical record comes in the form of notched bones, so-called “palaeolithic lunar counts,” as seen in this artifact:

30,000 year-old bone carving from Abri Blanchard (Dordogne, France)

which is said to represent the waxing and waning of the moon.

In 2002, decades after Alexander Marshackt discovered the lunar calendar on the Abri Blanchard bone above, archaeologists in South Africa discovered a geometric stone carving on red ochre thought to be 77,000 years old. Here are the earliest known traces of the subtle and enduring art of painting:

Carvings in red ochre from Blombos Cave

South Africa said to be 77,000 years old

Swedish writer Lasse Berg visited Blombos Cave in 2009 and wrote that since the discovery of the piece of carved ochre pictured above, similar carved stones engraved with geometric patterns have been found in the cave, a total of sixteen: “The oldest are at least 100,000 years old.” This amazing information Berg learned from archaeologist Christopher Henshilwood, Professor of African Archaeology at Bergen University in Norway, who specializes in Blombos Cave. This is an awesome period of time during which humans have engraved images on stone, bone or other materials. Berg compares the age difference between the oldest Blombos engravings and the one pictured above, as “about the same length of time between the oldest European cave paintings and Picasso.” Inside these caves in South Africa have also been found the oldest known human fire pits. Lasse Berg writes: “What we find here in Blombos Cave is the very foundation for everything that was to come.” (Skymningssång i Kalahari. Hur människan bytte tillvaro, Lasse Berg, Ordfront, Stockholm, 2012.

)

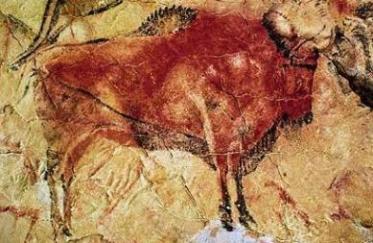

The birth of Art on the continent of Europe is usually seen as the unique heritage of the Homo sapiens. And yet, the Neanderthals as well had their artists. The species is named after Neandertal (“Neander Valley”), the location in Germany where it was first discovered. Neanderthals are believed to have existed in Europe over 350,000 years ago. After hundreds of thousands of years of nomadic existence in Europe, they suddenly disappeared around the time that our species, the Homo sapiens, began establishing itself around 43,000 years ago. Despite the fact that the adult Neanderthal brain was larger than the adult Homo sapiens brain, and that the two groups are closely related, paleontologists see an important distinction in the respective artifacts each left behind. As far back as 45,000 years, intricate sculptures by the first Homo sapiens artists reveal that Art is the deciding difference. Art is what made humans unique to all other animal species on earth. In the tiny carvings of prehistoric Venuses, men with lion-heads and the first pottery figurines, the unique intelligence of our species was manifest that would evolve into the intelligence needed to land machines on precise locations to within a few meters on distant planets, tens of thousands of years later. The cave painting below is one of six paintings which were discovered in the Nerja Caves, east of Malaga, Spain. They are the earliest known examples of European painting. Ironically these are not images painted by Homo sapiens. They are the only known images created by Neanderthal man, at least 42,000 years ago:

Art is one fathomless metaphor of awesome scope. In it are fossilized the mysteries of Creation – birth, life, death, rebirth – an eternally evolving metamorphosis. From the painted images of stone-age artists in ultra-archaic times, to the images of Matisse and Picasso in our own time, the various art forms have been gradually formed, along with all human knowledge. Before Art, animal shrieks and cries developed in accordance with the Way into language, and then stone-age artists plucked forth symbols from their souls that contained the power of image and sound in concentrated form. They doodled in the clay of river banks, on wood, stone and bone, inventing letters and numbers. These earliest artists took the letters they had created and formed the Word.

Cuneiform tablet from Sumeria

(courtesy Christopher L. C. E. Witcombe)

|

Ivory tags

oldest known examples of Egyptian writing, Abydos, 3,400 to 3,200 B.C.

(Courtesy Günter Dreyer) |

This accumulated knowledge tens and hundreds of thousands of years old has as its vessel today the creation of stone-, bronze- and iron-age artists: the alphabets and numbers. Whatever the epoch, Art has been the pathfinder, and its main function has always been to promote the spiritual health of the society at large. The arts need not refer only to such crafts as music, painting, poetry, drama and dance. Ideally the arts can also include government, economy, education, defence, commerce, science, mathematics, and just about everything human beings do. These very alphabetical symbols which I manipulate at present have as perhaps their earliest known beginnings the Duenos Inscription (left), dating from the 7th century BC. It is inscribed on the sides of a kernos, in this case three connected small spherical vases. It was found by in 1880 in Rome. The inscription was difficult to translate. It informs the owner of the vases that the perfume inside will help him if the maiden he fancies does not smile at him. This text is the ancestor of all the imperial inscriptions engraved in Latin on stone columns, porticos and facades throughout the Roman empire.

This accumulated knowledge tens and hundreds of thousands of years old has as its vessel today the creation of stone-, bronze- and iron-age artists: the alphabets and numbers. Whatever the epoch, Art has been the pathfinder, and its main function has always been to promote the spiritual health of the society at large. The arts need not refer only to such crafts as music, painting, poetry, drama and dance. Ideally the arts can also include government, economy, education, defence, commerce, science, mathematics, and just about everything human beings do. These very alphabetical symbols which I manipulate at present have as perhaps their earliest known beginnings the Duenos Inscription (left), dating from the 7th century BC. It is inscribed on the sides of a kernos, in this case three connected small spherical vases. It was found by in 1880 in Rome. The inscription was difficult to translate. It informs the owner of the vases that the perfume inside will help him if the maiden he fancies does not smile at him. This text is the ancestor of all the imperial inscriptions engraved in Latin on stone columns, porticos and facades throughout the Roman empire.

|

Venus of Willendorf

(ca. 26,000 years)

|

Woman (1952)

Willem de Kooning |

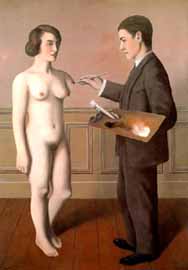

The history of western art is usually measured in millennia. The Venus of Willendorf (discovered in Austria in 1908) and de Kooning's Woman (above) illustrate that western art is an unbroken tradition of tens of millennia. The earliest known European paintings, created by unknown masters 30,000 years ago in caves in Spain and France, are the first examples of western art. One can only imagine what these strange individuals had for practical function in their respective prehistoric societies, but it is not far-fetched to believe that they were the veritable leaders. Erich Neumann, colleague of Carl Jung, pointed out in his book Art and the Creative Unconscious that the isolation of the modern artist from the rest of society was not always the case in human societies. In earlier primitive times, the artist was central to all aspects of the community, for the guiding principle of creativity was also the guiding principle of the society. The artist, ”whose vocation it is to represent the cultural canon,” wrote Neumann, remained in a mode of timelessness (which he termed ”participation mystique”) while his brethren became more and more preoccupied with time.

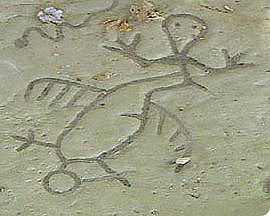

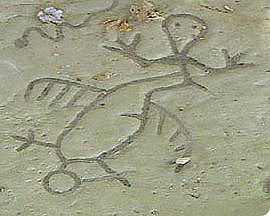

Pre-columbian petroglyphs

located near the village of Leo, Ohio, USA

|

Drawing by a modern child

|

Writing of Hieronymus Bosch (1450-1516), Neumann observed that the artist was now oppressed by ”one of the most modern problems of future generations: the Great Individual with his soul, alone in the mass of men.” The original situation where the creative principle was intimately integrated with community life, with the artist as middle man between Heaven and Earth, had disintegrated by Bosch's time. This despite the fact that the artist, in Neumann's words, ”is close to the seer, the prophet, the mystic.” Neumann's research clearly shows how there are similar motivations for creating in a child drawing with his crayolas and a prehistoric cave painter tens of thousands of years ago. (see above) Everyone experiences drawing and painting as children. This is our introduction to all the accumulated knowledge of our species at our disposal today, the first steps on the way to highly specialized professions, whether astro-physicist, molecular biologist or symphony orchestra conductor. The universal origins of creativity in human beings unite different cultures and epochs. With the insider’s deep knowledge of the art of painting, Vassily Kandinsky (1866-1944) explained this clearly as The Principal of Inner Necessity. Considering the vast degree to which this vital principle is ignored today (for it is the credo not only of the artist, but his connoisseurs as well), it is best to cite it in full:

THE PRINCIPLE OF INNER NECESSITY

1. Each artist, as creator, must express that which is unique to him. (Element of personality.)

2. Each artist, as child of his era, must express that which is unique to that era. (Element of the inner value of style, composed of the language of the people, as long as they exist as a nation.)

3. Each artist, as the servant of Art, must express that which is, in general, unique to Art. (Element of pure and eternal Art that one finds among all human beings, among all peoples and all times, that appears in the opuses of all artists, of all nations and all eras, and obeys no law of space and time as the essential element of Art.

Vassily Kandinsky

|

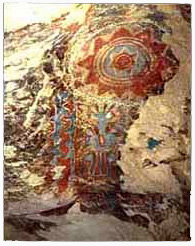

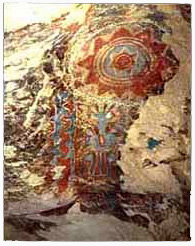

Unknown Chumash artist

Painted Cave, Santa Barbara, California

|

Depending on the epoch, one of Kandinsky's three points may take priority over the others. Artists creating from within great empires like Persia, Egypt, Greece and Rome tended to express that which was unique to the specific era in which they lived - the omnipotent power and wealth of the empire. In modern times, that which is unique to an individual artist tends to take priority over the era.

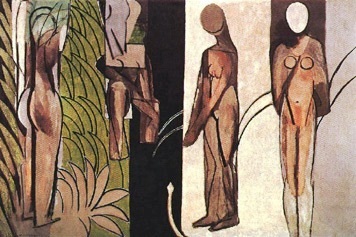

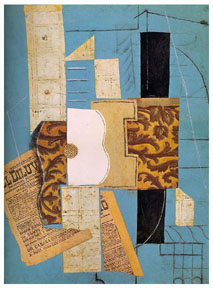

In the 20th century New York took over the postion of occidental cultural capital after Paris, with American art forms like jazz and abstract expressionism in the limelight. The Virginian painter Patrick Henry Bruce (below), a former student of Henri Matisse, experimented with cubism and fauvism and became one of the first American "abstract" painters.

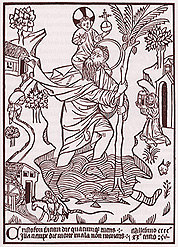

Among the techniques used by painters – oil, watercolor, collage, sculpture – is printmaking. Occidental printmaking, called le beau métier (“the lovely craft”) by French artisans, spans six centuries, beginning with the medieval masters of the woodcut who were the originators of books, passing by way of Dürer’s innovations to Rembrandt, Goya, Daumier, Whistler and so many more. Centuries before photography images of the great masterpieces of European art were seen by throngs of people in all corners of the world thanks to artisan printmakers. Although highly skilled, most were nonetheless merely scribes of images, tediously copying and bringing few innovations to their craft. It has been the great peintres-graveurs who brought innovation to this art which lies behind the printing of images and words on paper, most of all money. Printmaking was as important for Pablo Picasso as painting, since both arts are in essence one and the same. He consecrated himself to la gravure totally, bringing this art into the brilliant arena of his attention and intensely practicing it for sixty-eight fruitful years. Picasso’s graphic opus is said to be the most comprehensive in the history of western art. The images which Picasso printed on paper only go up and up in monetary value over the years, when the paper money printed by national treasuries only goes down, down, down in value.

Portrait of Françoise Gilot

195? (silkscreen)

Pablo Picasso |

.

Blind minotaur 1935 (etching)

Pablo Picasso |

Portrait of Dora Maar

194? (linoleum print)

Pablo Picasso |

The painter is a one-man state complete with department of treasury and department of war, “creating like a god, ruling like a king, working like a slave.” (Brancusi) When the peintre-graveur brings the art of painting into printing images of great value on paper, no government can rival his commerce. The painters were not only the creators of alphabets and numbers, they were the creators of minted and printed money as well.

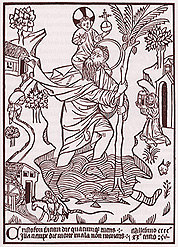

Saint Christopher 1423 earliest dated

European woodblock print |

Melancholia 1514 (etching)

Albrecht Dürer |

Faust in his study 1652 (etching)

Rembrandt |

Self-portrait 1798 (etching)

Francisco Goya | .

Rue Transnonain 1834 (lithography)

Honoré Daumier |

Billingsgate 1859 (etching)

James McNeill Whistler |

The Hand Eulogy 1958 (etching)

Joan Miró | .

untitled 1975 (etching, lithograph)

Antoni Clavé |

untitled 1970 (lithograph)

Willem de Kooning |

Romanticism, the yin to classicism’s yang, originated in the second half of the 18th century in Europe. It developed in defiance of the Industrial Revolution by maintaining strong bonds with nature, as heard in Beethoven’s Pastorale Symphony. Goethe called it the “Velocepedic Age” and prophesied increasing technological speed as being a curse on humanity. The Romantic artists did not experience the previous Age of Enlightenment as especially “enlightened” and Byron’s potent satire was aimed at the cant of this false notion and its reflections in a narcissistic and unhealthy society. Byron was a major inspiration to Romanticism throughout Europe and the Americas, a movement encompassing the visual arts, music, and literature, but also history, education and science. The prettiness and vanity that had dominated much of 18th-century art ceded to strong emotion as an authentic source of aesthetic experience, with new emphasis placed on such emotions as fear, horror, terror and awe. Such is often the subject matter of the two most remembered romantic painters, Théodore Géricault (1791 – 1824) and Eugène Delacroix (1798 – 1863):

The raft of the Méduse 1819

Théodore Géricault

|

The barque of Dante 1822

Eugène Delacroix

|

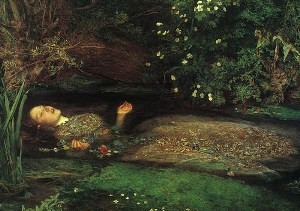

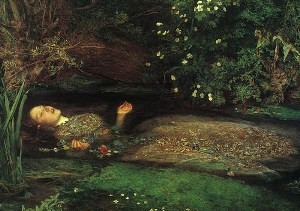

In 1848 John Everett Millais, William Holman Hunt and Dante Gabriel Rossetti met at the home of Millais’ parents in London and founded the “Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood”. Despite the studied Victorian elegance of their paintings (as in Millais' Ophelia below), they believed that Raphael’s elegant poses and compositions had been a corrupting influence on academic painting. Thus was born the idea of “pre-raphaelite” painting (which theoretically could include anything before Raphael, including the Lascaux cave paintings). By claiming kinship with the Quattrocento Italian and Flemish painters, they do not strike me as forward-looking painters in contact with real life, as were the Barbizon painters in France, who were their contemporaries. Their influence can be seen later groups like the the “symbolists”, “art nouveau“ and “surrealists“.

Ophelia 1852

John Everett Millais

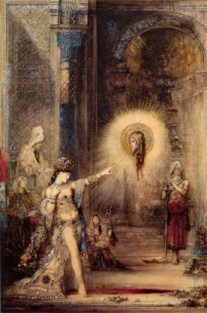

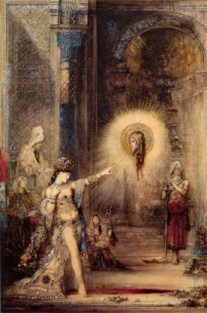

The symbolist painters (as well as poets) had their roots in Les Fleurs du Mal (1857) of Charles Baudelaire. The prose and poetry of Edgar Allan Poe, whom Baudelaire greatly admired and translated into French, were also a significant influence on the symbolists and the source of several images. Symbolist poetry was developed by Stéphane Mallarmé and Paul Verlaine during the 1860s and 70s. The symbolist paintings of artists like Gustave Moreau (1826 – 1898), Puvis de Chavannes (1826 – 1898) and Arnold Böcklin (1826 – 1898) (below) were distinct from, but related to, the literary movement of the same name, an outgrowth of the darker, gothic side of Romanticism.

Isle of the dead 1880

Arnold Böcklin

|

The apparition 1876

Gustave Moreau

|

Jeunes filles au bord de la mer 1879

Puvis de Chavannes |

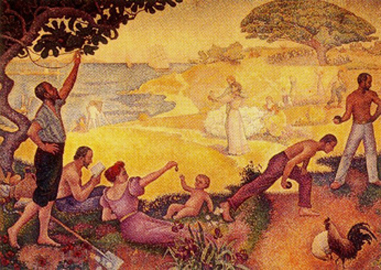

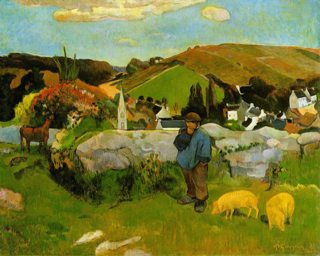

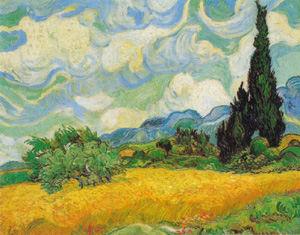

After centuries of visual tyranny derived from the Renaissance, impressionism came to western art as a breath of fresh air. The impressionist painters belonged to the generation after the Barbizon school of Millet, Courbet, Corot (below), and others. The Barbizon painters had a major influence on impressionists choosing “the great outdoors” as their studio. Impressionism was followed by neo-impressionism (also known as divisionism) and post impressionism. Among the neo-impressionists are Seurat, Signac and Cross. Among the post-impressionists are Cézanne, Van Gogh and Gauguin. These movements in turn gave birth to cubism, fauvism and futurism. A gradual evolution away from the Renaissance manner suddenly speeded up in the last three decades of the 19th century which in turn inspired multitudes of transformations in the 20th century.

This accumulated knowledge tens and hundreds of thousands of years old has as its vessel today the creation of stone-, bronze- and iron-age artists: the alphabets and numbers. Whatever the epoch, Art has been the pathfinder, and its main function has always been to promote the spiritual health of the society at large. The arts need not refer only to such crafts as music, painting, poetry, drama and dance. Ideally the arts can also include government, economy, education, defence, commerce, science, mathematics, and just about everything human beings do. These very alphabetical symbols which I manipulate at present have as perhaps their earliest known beginnings the Duenos Inscription (left), dating from the 7th century BC. It is inscribed on the sides of a kernos, in this case three connected small spherical vases. It was found by in 1880 in Rome. The inscription was difficult to translate. It informs the owner of the vases that the perfume inside will help him if the maiden he fancies does not smile at him. This text is the ancestor of all the imperial inscriptions engraved in Latin on stone columns, porticos and facades throughout the Roman empire.

This accumulated knowledge tens and hundreds of thousands of years old has as its vessel today the creation of stone-, bronze- and iron-age artists: the alphabets and numbers. Whatever the epoch, Art has been the pathfinder, and its main function has always been to promote the spiritual health of the society at large. The arts need not refer only to such crafts as music, painting, poetry, drama and dance. Ideally the arts can also include government, economy, education, defence, commerce, science, mathematics, and just about everything human beings do. These very alphabetical symbols which I manipulate at present have as perhaps their earliest known beginnings the Duenos Inscription (left), dating from the 7th century BC. It is inscribed on the sides of a kernos, in this case three connected small spherical vases. It was found by in 1880 in Rome. The inscription was difficult to translate. It informs the owner of the vases that the perfume inside will help him if the maiden he fancies does not smile at him. This text is the ancestor of all the imperial inscriptions engraved in Latin on stone columns, porticos and facades throughout the Roman empire.

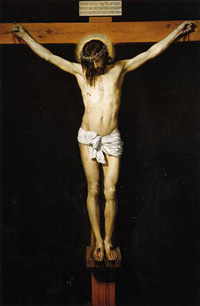

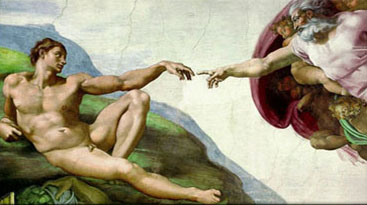

The 7th-century Viking rune stone (left) was discovered at Tängelgarda on the Swedish island of Gotland, in the Baltic Sea. It tells the saga of Odin, chief god of the Vikings, who was also their god of battle, death, and inspiration. He is seen here in procession on his horse Sleipnir. The disdain that some of my art teachers had for the ”crude” art of the Middle Ages is unjustified. Despite its lack of ”naturalism”, this example of European art 700 years before the Renaissance displays a high level of sophistication and mastery. The silence of the early Middle Ages may just represent a healthy moment of healing after centuries of Roman excesses preceding the centuries of excesses that we call the Renaissance. Not since Roman times was the human form naturally depicted. Giotto (below) reinvented soft rounded modeling effects using subtle gradations of light and shadow(chiaroscuro). Giotto marks the turning point toward the Renaissance. However much mastery and excellence the coming centuries of naturalistic painting displayed, the overall effect was a grotesque distortion of history and a fictionalization of not only Jesus, but of the whole saga of humanity. As a servant of Catholicism the Renaissance offered us an unreal fairy tale in which a child is conceived without sexual intercourse by an unseen deity inseminating a virgin, her adoring priests living in virtuous celibacy and providing healthy spiritual guidance to the innocent sheep in the pasture of Christ. How we were fooled!

The 7th-century Viking rune stone (left) was discovered at Tängelgarda on the Swedish island of Gotland, in the Baltic Sea. It tells the saga of Odin, chief god of the Vikings, who was also their god of battle, death, and inspiration. He is seen here in procession on his horse Sleipnir. The disdain that some of my art teachers had for the ”crude” art of the Middle Ages is unjustified. Despite its lack of ”naturalism”, this example of European art 700 years before the Renaissance displays a high level of sophistication and mastery. The silence of the early Middle Ages may just represent a healthy moment of healing after centuries of Roman excesses preceding the centuries of excesses that we call the Renaissance. Not since Roman times was the human form naturally depicted. Giotto (below) reinvented soft rounded modeling effects using subtle gradations of light and shadow(chiaroscuro). Giotto marks the turning point toward the Renaissance. However much mastery and excellence the coming centuries of naturalistic painting displayed, the overall effect was a grotesque distortion of history and a fictionalization of not only Jesus, but of the whole saga of humanity. As a servant of Catholicism the Renaissance offered us an unreal fairy tale in which a child is conceived without sexual intercourse by an unseen deity inseminating a virgin, her adoring priests living in virtuous celibacy and providing healthy spiritual guidance to the innocent sheep in the pasture of Christ. How we were fooled!

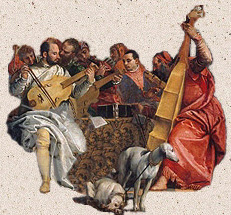

The ancient Greek deity Mnemosyne was known as ”Mother of the Muses” – the inspirational source of Art. The Greek word mousiké, the art of the muses, referred not only to music, but to painting, sculpture, poetry, dance, drama and all the other arts, which were ritualized with respective mysteries or initiation rites. The mystes or ”initiate” of the rites of Dionysos, Artemis and Demeter was instructed in each respective realm of knowledge – with drama as the realm of Dionysos. The overall mystery of Art began with painting in prehistoric times, with knowledge being passed on to a mystes or ”apprentice” as it would be during the Renaissance. The ultra ancient cave paintings are the beginning of history, although they are denoted as prehistoric. In many cave painting sites, flutes made of bone were found nearby. We can view stone-age paintings, but we can't listen to the stone-age music that would have been associated with many of the images. One sees the close connection between painting and music in the detail (left) of the musicians in Paolo Veronese's Marriage at Cana. Veronese himself plays the viola da mano, with fellow painters

Tintoretto (violin), Titian (contrabas) and Bassano (cornett).

The ancient Greek deity Mnemosyne was known as ”Mother of the Muses” – the inspirational source of Art. The Greek word mousiké, the art of the muses, referred not only to music, but to painting, sculpture, poetry, dance, drama and all the other arts, which were ritualized with respective mysteries or initiation rites. The mystes or ”initiate” of the rites of Dionysos, Artemis and Demeter was instructed in each respective realm of knowledge – with drama as the realm of Dionysos. The overall mystery of Art began with painting in prehistoric times, with knowledge being passed on to a mystes or ”apprentice” as it would be during the Renaissance. The ultra ancient cave paintings are the beginning of history, although they are denoted as prehistoric. In many cave painting sites, flutes made of bone were found nearby. We can view stone-age paintings, but we can't listen to the stone-age music that would have been associated with many of the images. One sees the close connection between painting and music in the detail (left) of the musicians in Paolo Veronese's Marriage at Cana. Veronese himself plays the viola da mano, with fellow painters

Tintoretto (violin), Titian (contrabas) and Bassano (cornett).

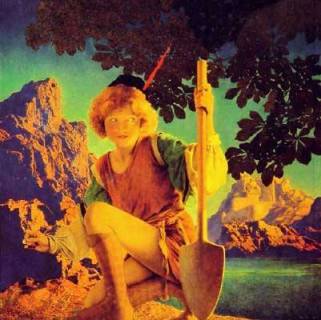

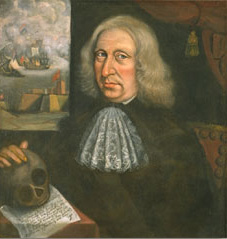

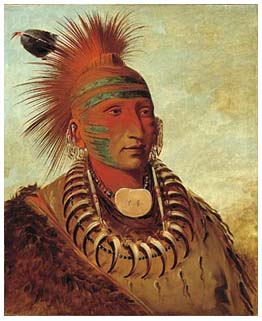

For almost 200 years before the existence of the United States, the European tradition of painting was being practiced in the Americas. Above right is a self-portrait by Thomas Smith from Boston dating from around 1680. Both Boston and Philadelphia would become cultural training grounds for future American masters. As traffic and trade increased between the Old and The New Worlds, new European techniques of painting and printmaking were being imported along with philosophic ideas, goods - and slaves. In 1784, as the “Age of Enlightenment” was occuring in Europe, the American patriarch painter Charles Willson Peale founded his Museum in Philadelphia as an Enlightenment temple. His aim was to “diffuse knowledge of the wonderful works of ceation, not only of this country but of the whole world.” (as quoted from Peale's selected papers in Catlin's Lament by John Hausdoerffer, 2009) This was for better and worse. The artist-scientist-curator-educator-entertainer Peale strongly felt that for proper study, Nature had to be isolated from its “savage state” and systematically archived in the clinical environment of a museum of natural history. At left is Peale's famous painting of his two sons Raphaelle and Titian in The Staircase Group from 1795. When I saw it at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, I was thrilled to see the final step emerge from the trompe l'oeil staircase as a real wooden step made not by a painter but a carpenter. (Infatuated with the European masters his other two sons were named Rubens and Rembrandt.) Many of the American masters had received expensive training from European masters in London, Paris, Munich and elsewhere. Their painting reveals considerable influence from such European movements as neo-classicism, romanticism, Barbizon school, impressionism, fauvism, cubism, etc. The similarities are as apparent as the differences. George Catlin began his painting career in Philadelphia strongly influenced by Peale's painting and philosophy. Despite belonging to the tradition of European painting, the works of George Catlin (below) and other painters of Native America reveal something unique to the continent of North America, something strange and new for European eyes.

For almost 200 years before the existence of the United States, the European tradition of painting was being practiced in the Americas. Above right is a self-portrait by Thomas Smith from Boston dating from around 1680. Both Boston and Philadelphia would become cultural training grounds for future American masters. As traffic and trade increased between the Old and The New Worlds, new European techniques of painting and printmaking were being imported along with philosophic ideas, goods - and slaves. In 1784, as the “Age of Enlightenment” was occuring in Europe, the American patriarch painter Charles Willson Peale founded his Museum in Philadelphia as an Enlightenment temple. His aim was to “diffuse knowledge of the wonderful works of ceation, not only of this country but of the whole world.” (as quoted from Peale's selected papers in Catlin's Lament by John Hausdoerffer, 2009) This was for better and worse. The artist-scientist-curator-educator-entertainer Peale strongly felt that for proper study, Nature had to be isolated from its “savage state” and systematically archived in the clinical environment of a museum of natural history. At left is Peale's famous painting of his two sons Raphaelle and Titian in The Staircase Group from 1795. When I saw it at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, I was thrilled to see the final step emerge from the trompe l'oeil staircase as a real wooden step made not by a painter but a carpenter. (Infatuated with the European masters his other two sons were named Rubens and Rembrandt.) Many of the American masters had received expensive training from European masters in London, Paris, Munich and elsewhere. Their painting reveals considerable influence from such European movements as neo-classicism, romanticism, Barbizon school, impressionism, fauvism, cubism, etc. The similarities are as apparent as the differences. George Catlin began his painting career in Philadelphia strongly influenced by Peale's painting and philosophy. Despite belonging to the tradition of European painting, the works of George Catlin (below) and other painters of Native America reveal something unique to the continent of North America, something strange and new for European eyes.

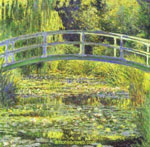

The term “impressionism” was coined after Claude Monet's painting Impression Sunrise (above) by a critic whose meaning was derogatory. Monet outlived most of the other impressionists and after years of poverty and neglect he became a living national monument for France. In 1889 he painted the famous Japanese bridge (left) at his retreat in Giverny. 52 years after Impression Sunrise, in the year of his death, Monet painted the bridge for the last time (below), displaying how far ahead of his time he was, like the fictitious Frenhofer in Balzac's novel Chef d'Oeuvre Inconnu. Along with his water-lily and haystack paintings, it reveals how Monet's vision is going more inward as the outward subject matter gradually loses its identity. The pure flow of colorful calligraphic brushstrokes takes on more and more importance, anticipating the “abstract expressionism” of Willem de Kooning's Composition 30 years later:

The term “impressionism” was coined after Claude Monet's painting Impression Sunrise (above) by a critic whose meaning was derogatory. Monet outlived most of the other impressionists and after years of poverty and neglect he became a living national monument for France. In 1889 he painted the famous Japanese bridge (left) at his retreat in Giverny. 52 years after Impression Sunrise, in the year of his death, Monet painted the bridge for the last time (below), displaying how far ahead of his time he was, like the fictitious Frenhofer in Balzac's novel Chef d'Oeuvre Inconnu. Along with his water-lily and haystack paintings, it reveals how Monet's vision is going more inward as the outward subject matter gradually loses its identity. The pure flow of colorful calligraphic brushstrokes takes on more and more importance, anticipating the “abstract expressionism” of Willem de Kooning's Composition 30 years later: