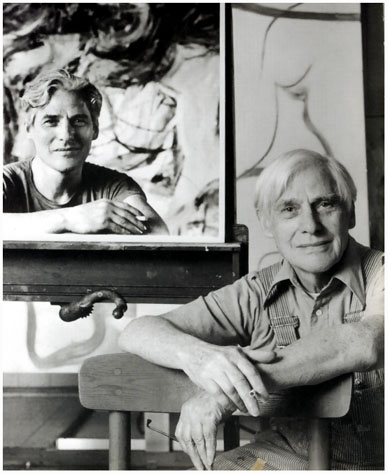

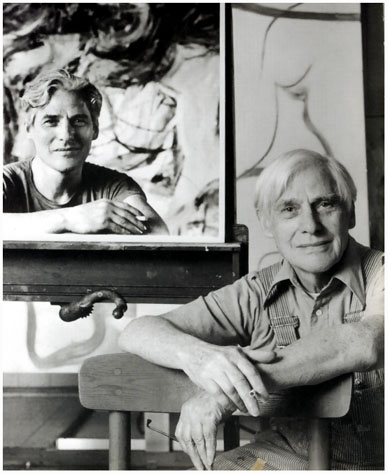

Willem de Kooning (1904 - 1997)

Photo by Hans Namuth

from De Kooning, Barbara Hess, Tashen, 2004

Willem de Kooning (1904 - 1997)

Photo by Hans Namuth

from De Kooning, Barbara Hess, Tashen, 2004

Hans Namuth's double photo-portrait of Willem de Kooning in 1991, six years before the painter's death, is mysterious and graceful like a Dutch interior. It is reminiscent of the other Dutch master, Vermeer, and the eerie harmony of this great magician of interior serenity. In the upper left quarter of the photo is de Kooning ("the king" in Dutch) as a young man, smiling, holding a lit cigarette. In the remaining three-quarters of the photo is de Kooning as an old man, smiling, holding a lit cigarette. This is the sublime artistry of de Kooning in one image, the smiling face behind the Women series and the Clamdiggers (see below), a full, round life like Shakespeare's, and the joke making him smile he will not share with us, enigmatic like the Sphinx.

Woman I (below) is an epoch-making work reminiscent of Picasso's Les Demoiselles d'Avyñon (left). De Kooning tried to destroy this endlessly re-worked painting in a fit of despair, thinking it to be a "failure". In his fury with the big canvases of the Women series for which Woman I was the prototype, de Kooning said "the smile was something to hang onto." In the Odyssey, when Menelaus, disguised as a seal, sneaks up on the Egyptian wizard Proteus, the wizard goes through miraculous visual transformations to deceive his captor and escape. To no avail. During the miraculous transformations of the Women, metamorphosed into all women from the dawn of time ("I didn't mean to make them such monsters"), de Kooning held onto the smile and prevailed. He himself said it was "like the smile of the Cheshire cat in Alice: the smile left over when the cat is gone."(1)

Woman I

Content is a glimpse of something, an encounter

like a flash. It is very tiny - very tiny, content.

- Willem de Kooning (1)

De Kooning excelled in the English language, which was for him a foreign language. He spoke no English when he arrived as a stowaway in New York in 1926. The eloquence that he later achieved is reminiscent of Picasso's eloquence in French, which was also a foreign language for him. De Kooning's precocious skill in English may even be linked to the fact that the original Angles and Saxons left his Holland and brought their language to England 1,400 years ago. The root of modern English can be found in the dialect of certain people in the Dutch countryside today, as if we are hearing a dialect of the ancient Anglo-Saxon language. De Kooning's witty expressions like "slipping glimpser" (see below) reveal a glimpse of a refreshing intelligence that is not rooted in verbal language, but in visual language. Predating alphabets and written languages is the painted image, origin of both. When western intellectuals speak of great "thinkers", they refer to philosophers and other writers. Few understand that master painters like de Kooning and Monet, and master composers like Shostakovich and Mahler, are subtle "thinkers" who surpass any philosopher.

De Kooning excelled in the English language, which was for him a foreign language. He spoke no English when he arrived as a stowaway in New York in 1926. The eloquence that he later achieved is reminiscent of Picasso's eloquence in French, which was also a foreign language for him. De Kooning's precocious skill in English may even be linked to the fact that the original Angles and Saxons left his Holland and brought their language to England 1,400 years ago. The root of modern English can be found in the dialect of certain people in the Dutch countryside today, as if we are hearing a dialect of the ancient Anglo-Saxon language. De Kooning's witty expressions like "slipping glimpser" (see below) reveal a glimpse of a refreshing intelligence that is not rooted in verbal language, but in visual language. Predating alphabets and written languages is the painted image, origin of both. When western intellectuals speak of great "thinkers", they refer to philosophers and other writers. Few understand that master painters like de Kooning and Monet, and master composers like Shostakovich and Mahler, are subtle "thinkers" who surpass any philosopher.

It is a fairy-tale coincidence that America's greatest modern painter left Holland, birthplace of oil painting, to live in the biggest city in the Americas founded by the Dutch: New Amsterdam. De Kooning's birthplace, Rotterdam, is not only the biggest port in Holland, it is the biggest port in all of Europe. I have entered and exited this monstrous port by ocean going ship, and have seen few ports that match its size. And from this region, 1,400 years go, the Angles and the Saxons used it as their port for sailing to England, and birthing the English language. De Kooning told Harold Rosenberg: "In Rotterdam you could walk for about 20 minutes and be in the open country."(1) And there, in what was at the time a rural "Barbizon" landscape, people spoke a tongue as they do today, very close in kinship with Anglo-Saxon. Native Americans would call this specific geographic region a "place of power" as is the specific geographic region of Los Angeles, with profound significance predating the cities founded on them. Combined with this geographic power of his birthplace, and the amazing tradition of master painters in Holland, Willem de Kooning as a phenomenon comes more into focus.

Many visual artists today do not feel the living link between us and the painters of the Lascaux and Altamira caves 30,000 years ago. The "Women" series of de Kooning does just that - establishes the living link between artists today and the creators of the "Venuses" sculpted tens of thousands of years ago. De Kooning was well aware of this link: "It is so satisfying to do something that has been done for 30,000 years the world over."(1) No other human discipline can claim such a direct connection with the most ancient manifestations of human knowledge. It is as if Hans Namuth's photograph at the top of this page continues into the past - de Kooning as a baby, back to Van Gogh, Rubens, Breugel, back to legendary Apelles, back, to the living human beings who painted the caves at Lascaux and Altamira. Who were they? Look at his smile!

There are many similarities between de Kooning and Picasso. Both received the highest level of classical training in the art of painting at a very early age. Picasso's teacher was his father, a highly trained painter from the academy in Málaga. De Kooning as well received years of classical training at the art academy in Rotterdam beginning at the age of twelve. The modern Dutch and Spanish masters evoke Rubens and Velasquez, and grew up in two of the most prolific nations in Europe for producing master painters. Both endured long years of poverty and privation to finally achieve total success. And in their art, de Kooning and Picasso both endeavored to elude their high level of competence and training. Eluding his competence, Picasso conceived cubism. Eluding his competence, de Kooning conceived abstract expressionism.

There are many similarities between de Kooning and Picasso. Both received the highest level of classical training in the art of painting at a very early age. Picasso's teacher was his father, a highly trained painter from the academy in Málaga. De Kooning as well received years of classical training at the art academy in Rotterdam beginning at the age of twelve. The modern Dutch and Spanish masters evoke Rubens and Velasquez, and grew up in two of the most prolific nations in Europe for producing master painters. Both endured long years of poverty and privation to finally achieve total success. And in their art, de Kooning and Picasso both endeavored to elude their high level of competence and training. Eluding his competence, Picasso conceived cubism. Eluding his competence, de Kooning conceived abstract expressionism.

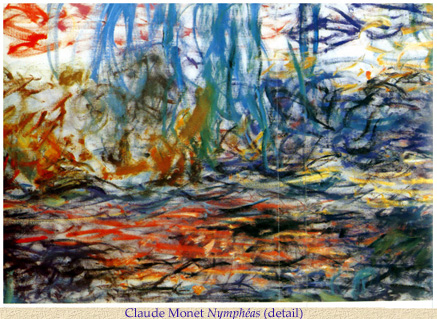

And both de Kooning and Picasso painted aggressive pornography in their old age, both obsessed by female genitals (de Kooning admitted that he was "cunt crazy"). Such a macho obsession - hardly a gesture of respect for women - can be contrasted with the serene lily ponds that Monet painted in his old age. Finally, de Kooning abandoned his obsession with both alcohol and female genitals, and began painting his last smooth and harmonious works that emanate a serenity like that of Monet - the calm after the storm. This inner calm was manifest in his last paintings despite the aging artist's severe Alzheimers dementia that left him unable to remember, verbally communicate or take care of himself. (De Kooning's dementia smiles from the photo below.) Around him swirled the dementia of unscrupulous people greedy for the treasure he could create at whim, like King Midas.

De Kooning's keen statements on the art of painting are of interest to everyone who loves painting. However, in their most refined essence, they are a personal message to other painters. In his famous interview with de Kooning, the art critic Harold Rosenberg is alert and tuned in to the painter's genius - a very rare occurance in art critics. But Willem de Kooning's personal message to other painters, now and to come, is understood only with the "gut feeling" of a bonafide painter. There are sweet degrees of artistry that remain forever beyond the perception of art-lovers, however much they may be possessed by oohs and ahs of appreciation, or Ph.Ds in art history. Where the most lucid perception of professional connoisseurs comes to an end, there begins the subtle realm that only artists know. Whether we wish to share these moments with non-artists or not makes no difference, because they cannot be conveyed to non-artists. Balzac put it this way:

De Kooning: If I made a sphere [without instruments] and asked you, "Is it a perfect sphere?" you would answer, "How should I know?" I could insist that it looks like a perfect sphere. But if you looked at it, after a while you would say, "I think it's a bit flat over here." That's what fascinates me - to make something I can never be sure of, and no one else can either. I will never know, and no one else will ever know.Rosenberg: You believe that's the way art is?

De Kooning: That's the way art is.(1)

(excerpt from Crazy Devil Sweeping)

"Abstract expressionism", like "impressionism", is the invention of wordy intellectuals – critics who are more in tune with words than with painting. De Kooning pointed out that the word "abstract" comes from "the light-tower of philosophers." In an essay for the bulletin of New York's Museum of Modern Art, de Kooning continued: "But one day, some painter used Abstraction as a title for one of his paintings. It was a still-life. And it was a very tricky title. And it wasn't really a very good one. For the painter to come to the 'abstract' or 'nothing', he needed many things. Those things were always things in life – a horse, a flower, a milkmaid, the light in a room through a window made of diamond shapes maybe, tables, chairs, and so forth."(2) [...]

By some odd coincidence, we were both born on April 24th (which was also the date of my mother’s death). In his heyday, de Kooning said at an interview of artists: "We have no position in the world – absolutely no position except that we just insist upon being around."(2) This is the idea of immortality. Back two thousand five hundred years, the fame of the Greek painter Apelles was first established. Not a single work by Apelles is known today and yet he "insists upon being around." Thus, Picasso once said that the legend an artist leaves behind is more meaningful than his opus. [...]

Art is absurd. Willem de Kooning once said that it is ridiculous to paint, but he does so anyway because it is even more ridiculous not to paint. De Kooning, like Catlin, exudes cheerfulness and humor. This is the true calling of the painter: exude cheerfulness and humor. [...]

.

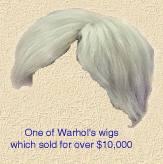

ANDY UNWIGGED

(a theory)

The wig’s the thing wherein we'll catch the conscience of the wannabe king. Like the silvery-wigged “in-crowd“ of 18th-century Europe, Andy’s wig was the main element of his public identity. They too, like Andy, took extreme care in storing and preserving their powdered wigs. Unwigged, Andy is a rather plain fellow. His main tool was not the brush, but the camera. The famous tomato soup can was created by an unknown commercial artist employed by Campbells Soup Company. In the case of the Mao Tse Tung portrait, Mao's official photographer, Lu Houmin, did all the creative work. The same with the portrait of Marilyn Monroe and the limited edition of silk screens of Mickey Mouse signed by Andy Warhol. Andy usurped these images created by other people, and filled in the contours like a child with his coloring book. And of course, the original creators of these images are over-looked by the “art world“ – to his benefit. Most maligned of these plagiarized creators is Leonardo da Vinci. Trendy art aficionados proudly announce that, ahem... “Warhol's“ Last Supper, a silk-screened photograph of Leonardo's mural, was auctioned for the equivalent of $10,000,000 in Sweden. If mentally retarded “art-lovers“ can be conned to this audacious degree, then the Con-man himself must be laughing from his grave.

The wig’s the thing wherein we'll catch the conscience of the wannabe king. Like the silvery-wigged “in-crowd“ of 18th-century Europe, Andy’s wig was the main element of his public identity. They too, like Andy, took extreme care in storing and preserving their powdered wigs. Unwigged, Andy is a rather plain fellow. His main tool was not the brush, but the camera. The famous tomato soup can was created by an unknown commercial artist employed by Campbells Soup Company. In the case of the Mao Tse Tung portrait, Mao's official photographer, Lu Houmin, did all the creative work. The same with the portrait of Marilyn Monroe and the limited edition of silk screens of Mickey Mouse signed by Andy Warhol. Andy usurped these images created by other people, and filled in the contours like a child with his coloring book. And of course, the original creators of these images are over-looked by the “art world“ – to his benefit. Most maligned of these plagiarized creators is Leonardo da Vinci. Trendy art aficionados proudly announce that, ahem... “Warhol's“ Last Supper, a silk-screened photograph of Leonardo's mural, was auctioned for the equivalent of $10,000,000 in Sweden. If mentally retarded “art-lovers“ can be conned to this audacious degree, then the Con-man himself must be laughing from his grave.

Thrilled at playing “master“ as children play at being “grown-up,“ Warhol also mimicked Picasso’s life-style in his “blue period” in Montmartre. Ordinary people did not understand de Kooning or Picasso, who were far ahead of everyone. Since Andy desired to please the POPulace who were uninterested in genius, and since he himself was no master, then why not imitate a master like a Hollywood movie star? And POP art was born (with a little help from Rauchenburg). World-famous interior-decorators, they feed the public's hunger for mediocrity. Although they covet the public's attention, the genuine artist is indifferent to it. His hard-won discipline suppresses futile and vain details in his art as in his personality.

The glamour of being a celebrity was all-important for Andy. De Kooning, however, shunned it. In 1968 there was a big retrospective exhibtion of de Kooning's work at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. After 42 years in the USA he returned to his native country in triumph. One man in Amsterdam said: "It's almost like the coronation." (New York Times, September 20, 1968) And yet, the adulation of the crowds and commotion of publicity-seekers was too much for de Kooning, who hated crowds, and he snuck out of the museum opening with his sister, relieved to escape the unpleasant situation. For Warhol, the group instinct of the crowd was his domain. The group instinct is an effective method of survival for humans as well as animals in the wild. But it does not give birth to great art. "The group instinct could be a good idea, but there is always some little dictator who wants to make his instinct the group instinct." (Willem de Kooning)(1) Warhol's art does serve a purpose, however, as illustrated by Plutarch’s observation of the master musician Ismenias of Thebes,

And thus, Andy Warhol the showman was a total publicity success. Yes, he is now listed beside de Kooning among the most important 20th-century American artists. But this mistake will eventually be corrected by Time (if we have enough of it left), and Warhol’s proper rank among painters will be remembered as a coquettish member of the “B team.” The “B-team” of 19th-century France, headed by “B” as in “Bouguereau,” was also given highest ranking by the critics and the public, to the detriment of the “A team” – Monet, Cézanne, Van Gogh and Lautrec. William Bouguereau sold his paintings (coveted in many countries) for astronomical prices. He, like Warhol, was a very POPular and kitchy artist. Bouguereau was briefly the teacher of Henri Matisse, who had no future as an artist according to Bouguereau. Because of this incorrect ranking of painters, Matisse endured repeated failures, despite his highest rank today. Warhol occupies a place like Bouguereau, mistakenly ranked among the best of his time. Although he was extremely famous in the 1870s, after 1920 Bouguereau fell from grace, and he is no longer ranked among the most important painters of his day. Contemporary art that dominates the taste of the general public ultimately does not dominate Time.

And thus, Andy Warhol the showman was a total publicity success. Yes, he is now listed beside de Kooning among the most important 20th-century American artists. But this mistake will eventually be corrected by Time (if we have enough of it left), and Warhol’s proper rank among painters will be remembered as a coquettish member of the “B team.” The “B-team” of 19th-century France, headed by “B” as in “Bouguereau,” was also given highest ranking by the critics and the public, to the detriment of the “A team” – Monet, Cézanne, Van Gogh and Lautrec. William Bouguereau sold his paintings (coveted in many countries) for astronomical prices. He, like Warhol, was a very POPular and kitchy artist. Bouguereau was briefly the teacher of Henri Matisse, who had no future as an artist according to Bouguereau. Because of this incorrect ranking of painters, Matisse endured repeated failures, despite his highest rank today. Warhol occupies a place like Bouguereau, mistakenly ranked among the best of his time. Although he was extremely famous in the 1870s, after 1920 Bouguereau fell from grace, and he is no longer ranked among the most important painters of his day. Contemporary art that dominates the taste of the general public ultimately does not dominate Time.

It took many decades for the mistake of ranking artists incorrectly to be rectified. It is no longer risqué to claim that Monet was by far superior to Bouguereau. Willem de Kooning is a master of Monet’s calibre. The difference between Warhol and Bouguereau, however, is that despite his “B team” ranking, Bouguereau was a bonafide master of the art of painting. Warhol is the pseudo-master of the extremely popular innovation in modern art: “piss paintings.” Art dealers and critics today not only covet Andy’s piss, but the piss of his followers, who were his “apprentices” (you know… like in the Renaissance), and who did the major "work" on the famous “piss paintings”, which sell for astronomical prices as do Andy's works today.

Pop art is shallow. Those who proceed with an in-depth exploration of color and form are seen as old-fashioned, not in step with the times. These popular pranks, although visual, are rather examples of literature. They must be explained in words. They emanate political or social symbolism that can be expressed verbally. These popular inventions are conceived on the same cultural wave-length as fast food, hard rock, punk, rap and pop music in general, while - far ahead of his times - de Kooning whistled Stravinksky's Rite of Spring as he painted. Few utterances are more futile than this complaint over the love of mediocrity in the arts. The 19th-century American master, James Abott McNeil Whistler, referred to this dilemma as the conflict between "the Mob and the Master". (The Gentle Art of Making Enemies)

In one of the many treatises on painting in Chinese culture, the twelfth-century painter Mi Yu-jen wrote about the "wisdom of the eye". This is a reciprocal requirement for both the painter and the viewer. Without the "wisdom of the eye" the painter will not go beyond mediocrity, and the viewer will be blind to genius. Judging by the mood of painting today, the "wisdom of the eye" is the rarest of all commodities in the west, along with Wisdom, plain and simple.

All artists, even Rembrandt, begin as mediocre talents. “Mediocre” means “half way up the mountain”. Everyone must pass this way. My complaint, therefore, is not against mediocrity, but its apotheosis by critics, curators, dealers, gallery owners and the general public who wish to democratize Art. They are all satisfied with a trek half-way up the mountain. Nothing is more undemocratic than artistic talent. Those very few who make it to the summit, receive divine instruction, and descend among their fellow humans, are left to wander like stray dogs, ignored for the most part until decades after their deaths. As western civilization proceeds further into downfall, the public turns into imbeciles in synchronization with our decline, obsessed by worthless baubles like Andy's wigs, gossipping about mediocre talents, disintegrating into their comfortable senility, thoroughly pleased with themelves.

Following World War II New York overtook Paris as an international center of modern art, due to a group of struggling painters identified by the critics as "abstract expressionists". (De Kooning was not satisfied with this name: "It is disastrous to name ourselves.") Like hyenas expectantly following the lion on his hunt, waiting to feast on the remains of his fallen prey which is too fleet-footed for them to capture themselves, the next generation only gave us pop art. Abstract expressionsm is the lion of modern American art. Unlike the dadaists and the pop artists, the "abstract expressionists" felt themselves to be, not the deniers, but the heirs of the great European masters. Since this mighty blossoming, there has been nothing of equal stature in American painting. What followed was deterioration.

The art students have established the status quo today. Galleries and museums proudly exhibit their POPular pranks, emanating what Warhol glibly remarked of his own work: “esthetic bankruptcy”. With POP art, POPularity and fame are the motivation, not visual excellence, which has been the motivation for painting for over 30,000 years. The first pop artist invented the “Eraced de Kooning” as an intellectual prank. The art critics were over-joyed at such cleverness. He quickly became world famous. But would he have eraced a Rembrandt? A Van Gogh? Was he able to replace the destroyed work with a greater opus? Rauchenburg’s prank at the expense of an artist greater than himself was very revealing - he revealed himself to be totally incapable of equaling de Kooning in the art of painting, let alone surpassing him. (Little does it matter that de Kooning personally gave him the drawing in question, along with his permission to erace - but not exhibit - it. De Kooning later regretted his generosity.)

Picasso called such pranks “lucubrations that are purely mental”, and saw them as “perhaps the principle error of modern art”.(3) These intellectual pranks, and the brief fame they generate, are the norm in art today, derived from the anti-Art movement called dada. First among the dadaists was Marcel Duchamp. Reminiscent of the intellectual vandalism done to de Kooning’s drawing, Duchamp drew a moustache on a reproduction of the Mona Lisa and these letters: L.H.O.O.Q. Pronounced in French they read: Elle a chaud au cul (“she has a hot ass”).

The dadaists followed the impressionists who, after long years of struggling with poverty and neglect, finally established themselves in art history as the masters they were. The dadaists, unable to achieve such mastery, chose to mock the masters instead, and created other criteria than Beauty as their motivation. They misunderstood Beauty as something "precious", something bourgeois that should be mocked and rejected. But Beauty as understood by Artur Rimbaud and Everett Ruess is something dangerous, filled with horror and dread, something like the sun, nourishing life at the same time as devastating, destroying and killing. A few decades after the dadaists, the pop artists followed in the footsteps of the abstract expressionists who, after long years of struggling with poverty and neglect, had finally established themselves in art history, several, like de Kooning and Kline, veritable masters. The pop artists, like the dadaists, unable to achieve mastery, also misunderstood Beauty as something "precious", something bourgeois that should be mocked and rejected in favor of their intellectual pranks.

In the to-the-death struggle between the Mob and the Master, only the Mob mocks the Master. While Duchamp publicly displayed contempt for the old masters, a greater painter, Henri Matisse, held them in high esteem his entire life. No artist creates from a clean slate. No artist can intelligently deny that thousands of years of painterly evolution precede his every gesture. Despite the phenomenal evolution of painting since Leonardo da Vinci, no true painter can justify contempt for this master, not even Duchamp.

De Kooning himself became a victim of his own fame, indulging in parties, alcoholic binges and casual sex, more and more influenced by the younger generation of excited artists and gold-digging young women. But the life style of a movie star, which was Warhol's raison d'être, soon became tedious for de Kooning. He abdicated his throne in lower Manhattan and, like a true painter (and to save his life), Willem retired from this glittering life of celebrities to his quiet studio in the Springs on Long Island. There he painted Pastorale in 1963, in homage to his late friend Arshile Gorky, who painted his own Pastorale in 1947.

It is hard to see the artist who is called "the father of 20th century painting" - Paul Cézanne - succumbing to this metropolitan temptation. It is the different (healthier) outlook of the "country boy" compared to that of the “city boy“ of so many artists seduced by New York and other huge cities, where fame is the lengua franca and meaning of life. The city boy de Kooning clarified: “I'm not a pastorale character. I'm not - how do you say that? - a 'country dumpling'“.(1) As a veritable “pastorale character“ who grew up with the jack rabbits and yuccas in Lytle Creek wash, I still feel that there is very much to gain from the down-to-earth experience of a “country dumpling.“

However famous at present, all artists must run the gauntlet of Time, in which only those works deemed exceptional are passed on to posterity. Art critics and museum curators have no knowledge of this process. Time will tell how the unwigged Andy Warhol fares running the gauntlet of generations.

La couleur surtout et peut-être plus encore que le dessin est une libération.

(Color above all and perhaps even more than drawing is a liberation.)

- Henri Matisse

Painting is poetry that one sees instead of feels,

and poetry is painting that one feels instead of sees.

- Leonardo da Vinci