The Cahuilla creator god Mukat has as his Mohave counterpart Matavilya, much as the Roman counterpart to the Greek god Zeus is Jupiter. The two myths are very similar. Both gods were bewitched and killed by their own people and cremated on a funeral pyre. In each myth Coyote stole the god’s heart, ate it and acquired forbidden power. Where the two myths differ is with Matavilya’s son, Mastamho, also known as Night Child. The Cahuilla myth does not mention a son of Mukat who created the Colorado river, which is central to Mohave cosmogony as the Nile is to Egyptian cosmogony.But the myth does mention the river once coming into Cahuilla and Serrano territory, and archeologists tell us that a great prehistoric lake – Lake Cahuilla – 35 miles across and 315 feet deep, was formed by the natural vagaries of the Colorado river. This lake was one of the largest fresh water lakes in North America, formed around A.D. 700 and remaining relatively stable for centuries, creating a fishing tradition and a veritable paradise for all the tribes living along its shores, where today are the harsh deserts of San Diego, Riverside and San Bernardino counties. This historical “side-trip“ made by the Colorado river is part of the Mohave myth related below.

This is the river known to the Mohave as Myahaim-tšumême. Mastamho made the river. There were no mountains then. The earth was level, wet and soft. Mastamho held a sun-staff of willow which was this long. At Hatasata he plunged it into the ground four times. Then water came out of the ground. Each time he plunged his staff in the ground various water fowl and fish and crustaceans emerged. Whenever he left his staff stuck in the ground, the water did not flow. But when he drew it out, the water and the fish and the birds came out. Mastamho then said,

This is the river known to the Mohave as Myahaim-tšumême. Mastamho made the river. There were no mountains then. The earth was level, wet and soft. Mastamho held a sun-staff of willow which was this long. At Hatasata he plunged it into the ground four times. Then water came out of the ground. Each time he plunged his staff in the ground various water fowl and fish and crustaceans emerged. Whenever he left his staff stuck in the ground, the water did not flow. But when he drew it out, the water and the fish and the birds came out. Mastamho then said,

– These are for the Mohave, but they do not yet know how to catch them. I will teach them.

The first one that came with the water was Yellak (Goose). Yellak began to trace the first route of the river, leading the dancing procession of water and feathers and scales over the desert, seeking out the deepest gulleys and sloughs. Now, as Yellak was leading the waters and animals southward, Mastamho ran ahead of them on the west bank, stopping at Ha’avulypo, where his father Matavilya had been cremated. There he set his staff in the center of the ashes, for he did not like to see them and wanted the water to wash them away.

So his father’s ashes would be swept away (along with his father’s house) as soon as Yellak arrived at Ha’avulypo with the new river. Then Mastamho went back quickly to Hatasata in the north (a voyage of four steps), and with his staff he stirred the waters emerging from the hole he had made, and a kasukye (boat) appeared. As the boat emerged, Mastamho put his foot on it, held it, entered it, and floated downriver behind the dancing procession led by Yellak.

Where the river was not broad enought to suit him, Mastamho stood on the edge of the boat until it lay far on its side. Then the river became wide there, and he continued rocking the boat to make valleys and the Grand Canyon. Then Mastamho took four steps north again to make Avikwame mountain. He repeatedly dropped mud left by the receding waters, and as it fell the mud said,

– Goloto!

like little boys say when they splash in the mud and play. Mastamho then said:

– Let the mountain be higher, and let the river flow by it.

And Avikwame became higher and higher. When the mud was dry, Avikwame was finished and that is where Mastamho lives still today. The world was wet then, but when the mountain dried, Mastamho assembled the first bards at the summit to instruct them. This is the beginning of the bird singers.

Meanwhile, Yellak had led the first waters of the Colorado west to what would be called the San Bernardino Mountains, and showed the birds how to move their wings. The waters and animals paraded behind him happily and Anya (Sun) blinked one time. And then a piece of driftwood got stuck on a sand-bar. Thick foam formed on it. Then the foam spoke. It said,

– Something!

Yellak spoke to the waters fish, crustaceans, plants and birds:

– Do not listen to what it says. We shall go on the right of it. That side of it is good and we shall take it. What the foam says is a lie. What I tell you I know: it is true.

The waters gurgled to the right of the driftwood log with its noisy foam prophesizing Yellak’s death. Near El Dorado Canyon, Yellak opened his wings and stretched them out so that the waters and birds could not pass. He was deadly sick and could not make it to the Ocean. The river was dammed with his outstretched wings at Ha’avulypo, center of the world. Now Yellak was quite dead. Only his heart was not dead yet. The dammed up waters were now wide behind his wings. He lay belly-up in the river. Yellak died at Ha’avulypo, where Matavilya was bewitched and killed by his daughter, Frog, long ago. Rock pinnacles on the edge of the river are the houseposts of the slain god’s dwelling, and the dammed waters behind Yellak’s outstretched wings nearly covered them. The Colorado river stopped in its tracks, uncertain of where to go.

Halykupa (Grebe) took Yellak’s place as leader of the waters. He ordered everyone to weep for Yellak, whose body was transformed into all the river and sea creatures. Qwilolo (Sea Urchin) was made from Yellak’ claws. Before leading the watery procession from Ha’avulypo, Halykupa, who was new at sorcery, thought things out and waited for knowledge to come to him. Now he knew he must go to the Ocean. Flapping his wings, he said:

Halykupa (Grebe) took Yellak’s place as leader of the waters. He ordered everyone to weep for Yellak, whose body was transformed into all the river and sea creatures. Qwilolo (Sea Urchin) was made from Yellak’ claws. Before leading the watery procession from Ha’avulypo, Halykupa, who was new at sorcery, thought things out and waited for knowledge to come to him. Now he knew he must go to the Ocean. Flapping his wings, he said:

– That will be all. Now let us stop crying.

And then he started waddling and all the waters and plants, fish and fowl, followed him southward once again. There was a bird in the procession named Minseatalyke to whom Halykupa said:

– Perhaps you have dreamed well. Perhaps you will be a sorcerer. I want to divide the waters here and let you take half of them. I will go on the eastern side, the true way. You can go your way, but you will meet me again. I shall not lose you.

And then Minseatalyke led half the waters west around Mathakeva (Cottonwood Island). He did not know much. He was not really going to be a sorcerer. Nonetheless he thought he was a great man. At the southern end of the island Halykupa was waiting for him, and all the waters were rejoined. Then Halykupa spoke to Minseatalyke:

– Do you see? You are not much. You have met me here after all. Alone, you could not dream your way to the Ocean. Now all will follow me and I will be the sole leader.

But even Halykupa was not much. He was afraid of passing Avikwame where Mastamho dwells. He thought to himself:

– Perhaps he will overcome me. Perhaps he will not let me pass. When we come to Avikwame, perhaps I will be caught and killed.

Hearing a great noise coming from the mountains, Halykupa named the river: Myahaim-tšumême. The waters were happy and calm again, following Halykupa diligently. The river flowed straight and Halykupa led it quietly past Avikwame. There were no rapids. He was afraid of Mastamho. Perhaps he would be bewitched. Or perhaps he would dream and acquire great power. He told all those following him not to listen to the great noise coming from the mountains, which was Mastamho’s voice calling them to Avikwame.

Hearing a great noise coming from the mountains, Halykupa named the river: Myahaim-tšumême. The waters were happy and calm again, following Halykupa diligently. The river flowed straight and Halykupa led it quietly past Avikwame. There were no rapids. He was afraid of Mastamho. Perhaps he would be bewitched. Or perhaps he would dream and acquire great power. He told all those following him not to listen to the great noise coming from the mountains, which was Mastamho’s voice calling them to Avikwame.

– If you hear his voice and go, he will do something to you. Then perhaps you will acquire a sorcerer’s power. But you will not be happy. Listen to me and follow me. Do not go aside and it will be well.

Mastamho thundered:

– I want you all to come here to me because it is I who have power.

Halykupa urged:

– Do not do it! Come down to the Ocean with me.

Wisely the waters followed Halykupa and when they came to the rapids they were prepared. All the birds obeyed him except two: Humathe (Condor) and Gnatcatcher. Humathe flew off to Avikwame wearing a bracelet and belt made of shells. Gnatcatcher stayed behind and claimed both sides of the river as his own. This was the beginning of the Mohave people. There were no other problems until they came to Needles. Then White Beaver stood before Halykupa trying to dam the river, saying:

– I am the chief of all. I am better than you. You cannot pass here.

He turned his flat tail on edge and with it stopped the river so that it stood still and flowed back. But Halykupa was not intimidated. He went to the side and back again, and again to the side and back four times, thinking:

– He is unable to stop me!

And that is why the river zig-zags at that place today. When Halykupa told his followers that they would become birds they did not believe him. Already their feathers had begun to sprout and yet they did not believe him. Halykupa named Woodpecker and sent him flying off to the east. Then Ahmá (Quail) went off west. Then they all slept. Halykupa did not sleep, but like all grebes, submerged his body and rested with only his head protruding. Sákumaha (Oriole) was the first to wake up and tried to sing the others awake. But they slept on. Then Orró (Night Hawk) awoke long before dawn. He spat on his hands and rubbed white streaks on his upper arm and across his jaw, and blew saliva over himself. He lied to the others, saying:

– It is morning! Wake up!

But they knew that it was not yet day and did not wake up. Finally Sakwatha’alya (Mockingbird) chattered the waters awake and the river widened out. Halykupa finished making their bodies from the remains of Yellak and then taught them how to lay eggs:

– Raise your right wing and flap it against the female like this. Lift your wings and strike them on the water and make foam like this. It is only in this way that you can lay eggs.

Hanyiwílye (Mud Hen) followed his advice and laid four eggs. The others imitated her. They walked over the desert and became tired and thirsty. They drank the rain and rustled their feathers, following Halykupa south. Then they heard a rushing noise and smelled salt in the air. They were all very eager to enter the Gulf of California. All the birds wanted to be first to the sea. They wanted to race the waters which were already moving the reeds and canes. These latter were bolts of lighting which had been embedded in the river. The first time that cane grew, it grew here. Then it made a loud noise and thunder entered its roots. That is the speech of the cane. (The twin sons of Gopher, Para'aka and Parahane, enchanted by the pleasant sound, made the first cane flute.) But Halykupa warned the racing birds:

Hanyiwílye (Mud Hen) followed his advice and laid four eggs. The others imitated her. They walked over the desert and became tired and thirsty. They drank the rain and rustled their feathers, following Halykupa south. Then they heard a rushing noise and smelled salt in the air. They were all very eager to enter the Gulf of California. All the birds wanted to be first to the sea. They wanted to race the waters which were already moving the reeds and canes. These latter were bolts of lighting which had been embedded in the river. The first time that cane grew, it grew here. Then it made a loud noise and thunder entered its roots. That is the speech of the cane. (The twin sons of Gopher, Para'aka and Parahane, enchanted by the pleasant sound, made the first cane flute.) But Halykupa warned the racing birds:

– No, do not hurry. Wait until I tell you. The sea is not good water. It is salty. If you jump into it, you will not be able to fly.

The Colorado river reached the sea for the first time after a very long journey over the desert, carrying in its current the ashes of Matavilya. But Halykupa, Wood Duck and one other bird became homesick at the seashore and longed to return to Gnatcatcher’s (Mohave) country. It was their secret desire to go to Avikwame and acquire great power. Halykupa reasoned:

– The sky is not very far away. The earth is not very far away. Avikwame cannot be far away.

They gathered shells to take back with them and then jumped high up into the air four times. Half-way up to the sky they hovered like three satellites, and, looking down, they saw the great ocean in the west beyond the slender penninsula of Baja California. Directly below them was Avikwame mountain. Halykupa said:

- Didn’t I say so? The sky is not far away and Avikwame is directly below us!

Halykupa flew straight down and tried to land on Avikwame, but he did not reach it. He landed on the wrong mountain, as did Sakatathêre and Wood Duck. In Gnatcatcher’s country Sakatathêre crushed the shells he had with him in his hands and scatttered the dust on the ground.That is why the earth is white there. They slept on the white ground. High up on Avikwame, Mastamho stood in the center of the mandala at the summit, transforming people into hawks. Halykupa and the other two birds awoke and went to Avikwame. When they finally were standing before Mastamho, the god said:

– Come here! Sit down!

Then they watched as he turned people into hawks, throwing them up into the air by their right arms. The bird-doctors sat around Mastamho as he transformed them one by one into various birds. Then he told them all to fly away, which they did. All except one, that is: Halykupa. Poor grebe, he tried to fly with the rest of the birds, but could not. He could only walk. So he walked off and jumped into the slough beside the river and did not leave the water ever again. He lives there today, still unable to fly. Then Mastamho said:

– I have finished everything. My sun-staff pierced the ground at Hatasata in the north and the waters reached the gulf in the south. All the others have flown away. Now I too will fly away.

And so, when Mastamho’s work was done, he transformed himself into Eagle. Then he went to the sky. Today, Mohave, Serrano and Cahuilla Bird Singers still sing the traditional songs of the migratory birds, just as Mastamho and Mukat instructed.

EPILOGUE

This, the second largest river in North America, no longer reaches the Gulf of California due to its over-exploitation by Americans. The mythic songs of the Mohave – Aha Macav – led Alfred Kroeber, his wife and a student through Mohave territory. These songs also had a navigational function for the Mohave, who were great travelers, trading with people on the Gulf of Mexico and the Pacific coast. To find their way over the vast desert regions of the Southwest, and to correctly time their treks, the Mohave travelers sang these songs to locate landmarks and water sources along the way. Many of these were Bird Songs, inspired by the habits of migratory birds. There were hundreds of these songs, each to be sung in a determined sequence, and maintained by families and clans who were forbidden to intermarry within their own song group to assure their vitality.

Many of these songs concern Avikwame – Spirit Mountain – and Grapevine Canyon, called “the spiritual gateway to Spirit Mountain,” where petroglyphs one thousand years point the way to the gods. Today, the Mohave, Chemehuevi, Cocopah, Quechan and other Colorado river tribes wage veritable war against the government to prevent Ward Valley and nearby Grapevine Canyon from being used as a radiocative waste dump. Only fragments of these ancient songs are sung today. In Parker, Arizona, in 1972, Mohave elder Emmett Van Fleet, one of the last epic singers (then 82 years old), sang some of the songs in their entirety for an ethnographer who recorded them on magnetic tape. Today these tapes are guarded as sacred relics among the People of the River. (“The Song of the Land,” Philip M. Klasky, News from Native California, Fall 1998.)

The last scholarly task which Alfred Kroeber completed was the third in his trilogy of Mohave myths: More Mohave Myths. (The first and second of these are Seven Mohave Myths and A Mohave Historical Epic.) Theodora Kroeber, along with Robert Heizer, saw the final version of More Mohave Myths through printing after Kroeber's death. In the preface, Kroeber's wife wrote: “The scientist Kroeber and more than a little of the artist Kroeber are palpable in the Prologue/Eplogue, and the man in both aspects may be followed by way of a delicate clue through the tales and what he says about them.” Kroeber was originally a New Yorker, but after a long and fruitful life emersing himself in Native Californian cultures, he was thoroughly a Californian. Another prominent figure in Native California originally from the east coast, the publisher Malcolm Margolin, once told me that Kroeber came to California fresh from Columbia University and, like an animal in the wild marking the boundaries of his domain with secretions, he immediately “marked” his primary domains: the Klamath/Trinity rivers of the Yurok, Karuk and Hupa; and the Colorado river tribes, most specifically the Mohave.

Kroeber’s first contact with the Mohave was in 1900, and his last in 1953. Kroeber's first and last field trips were in Mohave territory. Accompanied by his wife and a graduate student on the last field trip, he retraced the epic routes that are crystalized in the vast network of Mohave myths, centered around Avikwame mountain. Theodora Kroeber continued in her preface: “On the desert and on the river Kroeber and his companions followed the dreams, mapping them as minutely as they could. In a shallow-bottomed boat, which would not hang up on the shifting red-silt peaks that build up under water from the river bed, they even reached Avikwama, the place of origin of the Mohave people. There they beached their boat and took pictures of that old and sacred site where everything began.” (excerpt from The Whetting Stone)

An email from artist and friend Richard Cordero adds this interesting information: "According to one source, the word Mojave comes from two Indian words, aha (meaning water) and macave (meaning along or beside). 'Mojave' therefore translates as 'along or beside the water.' When applied to the Mojave Indians, it translates as 'the people who live along the water,' referring to the Colorado River." Note: It is unclear whether Kroeber's spelling "Mohave" or "Mojave" is the correct spelling.

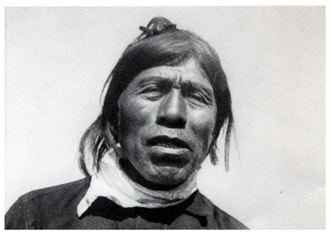

Epic Mojave bards (1902-05)

|

|

|

|

Sources:

Alfred Louis Kroeber, More Mohave Myths, Anthropological Records vol. 27, UC Press Berkeley, 1972: “Yellak”, recited in the Mohave language by Aspá-sakám (Eagle Sell) in November 1905, interpreted by Kwatnialka (Jack Jones).

Alfred Louis Kroeber, Seven Mohave Myths, “Mastamho Myth”, recited in the Mohave language between November 16-24, 1903 by Jo Nelson, interpreted by Kwatnialka.