[Home] [How To Move The Pieces] [Rules]

[Strategy] [How To Take Notation]

How to Check, Checkmate, and Stalemate

Castling is the only move that involves shifting two pieces instead of just one. The point of castling is to protect the king by tucking him away on the far side of board nestled beside one of his rooks.

Here's how it works.

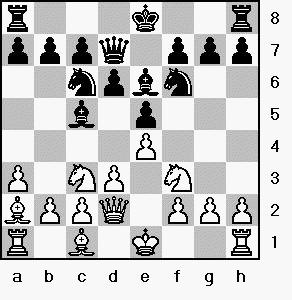

First, castling is only possible when there are no pieces between the king and a rook:

In the above example, White is able to castle on the king's side of the board, but can't on the queenside, because the bishop remains between the king and the rook. Black, on the other hand, can choose to castle on either side of the board.

You castle by first moving the king two spaces sideways toward the rook. Then you pick up the rook, lift it over the king, and place it on the square immediately beside the king. Here's what the board looks like after both sides have castled:

Note that it's possible to castle on either side of the board. When you castle on the king's side the king lands one square from the edge of the board, on the queen's side, the king ends up two squares from the edge.

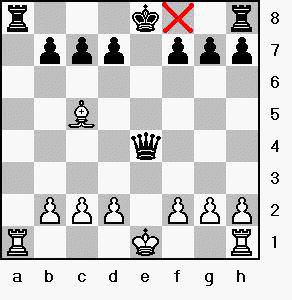

There are several important instances when castling is forbidden. You cannot castle when your king is in check. You also cannot "castle through check"; in other words, you cannot castle if you would have to move the king across a square that is attacked by an enemy piece. (And, of course, castling can't take place if the square the king will land on is attacked by an enemy piece.) Here's an example:

In the above picture, White can't castle at all because his king is in check. Black can't castle kingside because the white bishop attacks the square marked with the red "x". Note that Black can still castle on the queenside, even though one of the pawns has been removed and his rook is being attacked.

All the above are temporary bars to castling. If the check goes away, castling can still take place.

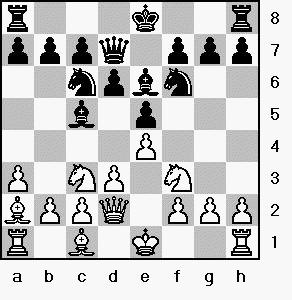

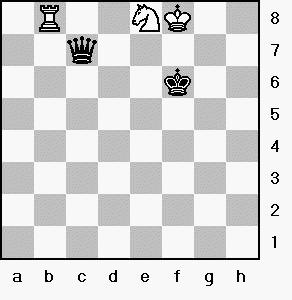

However, if the king moves, then castling can no longer happen. If a rook moves, then castling is no longer possible on that side of the board:

Here, White's king has moved, so castling is now permanently forbidden. This is the case even if the king moves back to its original square. Black can still castle on the king's side, but can't on the queen's side, because the rook there has shifted position.

We've seen earlier how pawns move and capture.

However, there is one special pawn move that many social players of chess don't even know about! Take a look at the following position:

Black has just moved the pawn in front of his queen ahead two squares. Notice that there is now a white pawn right beside it.

That white pawn can now legally capture the just-moved black pawn as if that black pawn had only been moved one square forward:

After this capture, the board now looks like this:

And that's an en passant capture.

Just remember that to capture a pawn en passant, the pawn to be taken has to have just moved from its starting position two squares forward. So, if your pawn sits directly beside an enemy pawn that has just moved those two squares forward, you can take that enemy pawn en passant.

One last reminder. This is a limited time offer. In other words, you can't wait for another turn to capture a pawn en passant -- you either do it right after the enemy pawn has moved, or you can't do it at all.

We already know about regular pawn moves, and the special en passant capture. But there's still one more pawn trick we haven't seen: promotion.

If you march a pawn all the way across the board to your opponent's side, you get a big reward. A pawn that makes it completely to the other end is "promoted", or in other words, instantly changed into any piece of your choosing (except a king).

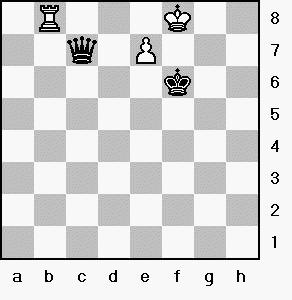

In the image below, White has the move. Here's what the board looks like just before White moves:

...and right after:

About 99.9% of the time, players chose to promote their pawns to queens, which is only logical, given that they are the most powerful pieces on the board. But every once in a while, it's best to select another piece when promoting a pawn.

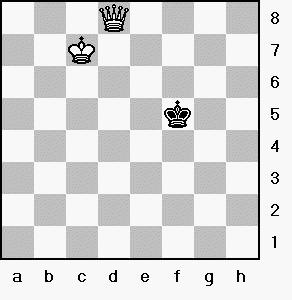

The board below shows a position where it's to White's benefit to under promote, that is, turn the pawn into something apart from a queen:

If White promotes the pawn to a knight, then Black's king and queen are both attacked. After Black's king moves -- because he's in check, the king has to move -- White can take the queen and go on to win:

How to Check, Checkmate, and Stalemate

We've finally arrived at the heart of the matter. The whole goal of a chess game is to checkmate your opponent's king. Achieve checkmate, and you've won.

A king is in check if it is attacked by an enemy piece. Here, the Black king is in check:

It is against the rules of chess to allow your king to be captured. So, if your king is in check, then you absolutely must do something on the very next move to remove your king from check. In this case, Black can either move the king:

...or place a piece in front of the king to protect him:

Note that you can never move your king to a square where he will be in check. Nor can you move one of your own pieces if to do so would expose your king to check.

Your king is checkmated if he is attacked, and there is no way to remove him from the attacking check. If you are checkmated you lose the game. If you checkmate your opponent, you win.

Here are just a few examples of the many ways in which a king can be checkmated:

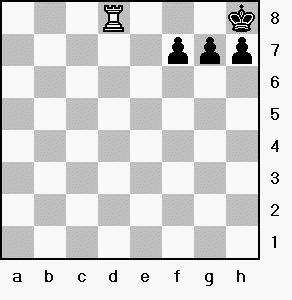

Finally, always be on the lookout for "stalemate". A king is stalemated if he is not in check, but the only moves available would put him in check. If this happens, the game is declared a draw.

Here's an example where Black's king is in stalemate. Black's pawn is blocked, and Black's king has no move that wouldn't put him into check:

If the white pawn weren't there, though, Black would not be in stalemate.

© David Leckner 2002