MIRROR LAKE J.E. TEMPLE PETERS BONNIE & CLYDE

REC BUILDING RANGER HIGH SCHOOL TRAIN ROBBERY

WALTER PRESCOTT WEBB SALOONS & CABARETS PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH

BYRON PARRISH FIRST BAPTIST CHURCH

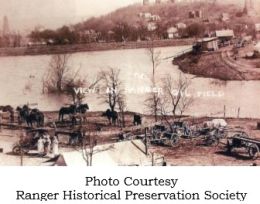

MIRROR LAKE - Early on, Ranger recognized the importance of recreational

facilities. During the oil boom, planning began for a park at Mirror

Lake, on what used to be the J. M. Rice (James Monroe Rice, 1844-1917)

property at the west end of Main Street. John Rust, J.M. Rice’s grandson,

recalled in the Oral History of the Texas Oil Industry (Dolph Briscoe

Center for American History, University of Texas at Austin) that his

grandfather’s lake was an early source of water for Ranger.

A 1919 newspaper article announced that developers, the Black Brothers,

held a ten-year lease on Mirror Lake, as well as on five acres adjoining

it. They intended to develop the area into a park. A springboard and a

sliding chute were installed at Mirror Lake, and designs for a bathhouse,

recreation room, and boathouse were developed by a local architectural

firm.

The entertainment center was to have its floor refinished to make it

suitable for dancing. Tables, benches, and swings were added to the park.

Paul Daily, a landscape gardener from Arizona, was in charge of park

beautification. A water pumping station was installed to supply water

for the park lawns and to provide fire protection. The plans included

six steel rowboats, all available for rental. A postcard advertised

Mirror Lake’s bathing beach. The developers planned to stock the Lake

with fish.

Mirror Lake is pictured in a 1921 West Texas Chamber of Commerce

publication touting Ranger’s attractions. Eventually the park was

supplanted by a park across the street to the east. The lake in that

park was in turn replaced by a swimming pool, part of Willow Park

(also called Willows Park or City Park). Mirror Lake continues in

name although not as the park that the developers envisioned. A

recent Eastland County Today news item mentioned that Mirror Lake

had some water in it following heavy rains.

Mirror Lake in Ranger

J.E. TEMPLE PETERS - was one of the four teachers in Ranger between

1899 and 1902. He became co-principal in 1902 and then head of the

school in 1904. Before 1914 the school system was considered too

small for the head of the school to be called superintendent. He

served in the role of what would now be called superintendent until

1908. Under his guidance the six-room red brick school building was

built in 1905, replacing a wooden structure. During his tenure the

number of teachers rose from four to seven.

Walter Prescott Webb, later a member of the University of Texas

history faculty and noted historian, was one of Peters’ students. Webb

remembered him as an extraordinary teacher, who had an almost hypnotic

effect on his students. In addition to the usual academic subjects,

he took the boys aside for other lessons: they should tip waiters,

have their shoes shined, send candy to their dates, wear clean linen

and tailor-made clothes, and stay in the best hotels, if they could

afford it.

After leaving Ranger he became teacher and principal in schools in

Scranton, Cisco, and Abilene. He returned to Ranger to manage the

Chamber of Commerce. Afterwards he managed Chambers of Commerce in

Denison, Stamford, and Cisco. Eventually he served as liaison officer

with the Texas Legislature for all the Chambers of Commerce of Texas.

His final position was a department head with the Dallas office of

the U. S. Department of Agriculture, from which he retired in 1947.

Joseph Evans Temple Peters was born in Patchenville, Steuben County,

New York October 8, 1879. He came to Texas in 1892 with his parents,

Rev. and Mrs. John H. Peters. They settled first in Menard and then

presumably in Rising Star, since he graduated from Rising Star High

School with a first-grade teaching certificate. Soon thereafter he

was in Ranger: he is in a picture of Ranger’s first baseball team,

probably taken after the team was declared champions in 1898-1899

after defeating the Thurber Black Spiders. Also soon after arriving

in Ranger, he began his illustrious career as teacher and head of

the Ranger school.

He married Vera Charlton Rawls, one of his former students (she is

in a 1903 picture of his class). They had three children, only one

of whom, William Charlton Peters, survived childhood. Vera preceded

her husband in death. He then married Cordelia (“Dee”) Bacon Gross,

a widow. She had been one of the teachers in Ranger when Peters was

a teacher and then head of the school. He died April 30, 1967.

Mirror Lake in Ranger

J.E. TEMPLE PETERS - was one of the four teachers in Ranger between

1899 and 1902. He became co-principal in 1902 and then head of the

school in 1904. Before 1914 the school system was considered too

small for the head of the school to be called superintendent. He

served in the role of what would now be called superintendent until

1908. Under his guidance the six-room red brick school building was

built in 1905, replacing a wooden structure. During his tenure the

number of teachers rose from four to seven.

Walter Prescott Webb, later a member of the University of Texas

history faculty and noted historian, was one of Peters’ students. Webb

remembered him as an extraordinary teacher, who had an almost hypnotic

effect on his students. In addition to the usual academic subjects,

he took the boys aside for other lessons: they should tip waiters,

have their shoes shined, send candy to their dates, wear clean linen

and tailor-made clothes, and stay in the best hotels, if they could

afford it.

After leaving Ranger he became teacher and principal in schools in

Scranton, Cisco, and Abilene. He returned to Ranger to manage the

Chamber of Commerce. Afterwards he managed Chambers of Commerce in

Denison, Stamford, and Cisco. Eventually he served as liaison officer

with the Texas Legislature for all the Chambers of Commerce of Texas.

His final position was a department head with the Dallas office of

the U. S. Department of Agriculture, from which he retired in 1947.

Joseph Evans Temple Peters was born in Patchenville, Steuben County,

New York October 8, 1879. He came to Texas in 1892 with his parents,

Rev. and Mrs. John H. Peters. They settled first in Menard and then

presumably in Rising Star, since he graduated from Rising Star High

School with a first-grade teaching certificate. Soon thereafter he

was in Ranger: he is in a picture of Ranger’s first baseball team,

probably taken after the team was declared champions in 1898-1899

after defeating the Thurber Black Spiders. Also soon after arriving

in Ranger, he began his illustrious career as teacher and head of

the Ranger school.

He married Vera Charlton Rawls, one of his former students (she is

in a 1903 picture of his class). They had three children, only one

of whom, William Charlton Peters, survived childhood. Vera preceded

her husband in death. He then married Cordelia (“Dee”) Bacon Gross,

a widow. She had been one of the teachers in Ranger when Peters was

a teacher and then head of the school. He died April 30, 1967.

T.E. Temple Peters

BONNIE & CLYDE - The famous, the not-so-famous, and the infamous:

visitors to Ranger and passers-through usually fit into one of these

categories. Probably no one fit better in the “infamous” category

than Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow. They met in 1930 but were

separated when Clyde went to prison on burglary charges. He escaped

but was recaptured a short time afterwards and sentenced to 14 years

in the state penitentiary. He was paroled in 1932, and he and Bonnie

reunited.

With other members, including Clyde’s brother Buck, the Barrow gang,

as it began to be called, committed a series of holdups throughout a

several state area—banks, filling stations, restaurants, in short any

place that might have some cash available for the taking. In the course

of their holdups and escapes, they murdered at least 13 people (sources1

differ as to the exact number) including law officers. Buck was killed

in one of the escapades. The Barrow gang’s exploits over a little more

than two years made national headlines. One writer pointed out that in

a way, the Barrow gang provided entertainment for a nation in the throes

of the Great Depression.

In January 1934 the gang made a daring and successful attack on a Texas

prison, freeing convicted bank robber Raymond Hamilton, who had been a

member of the gang before he was caught and imprisoned. They also freed

Henry Methvin, and he joined up. Members of the gang came and went, the

latter sometimes as a result of quarreling among themselves. At some

point Hilton Bybee joined the group.

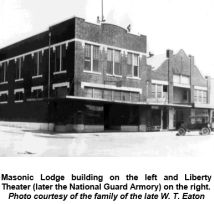

Fresh from successful robberies in several states, the Barrow gang came

to Texas, Bonnie and Clyde’s home state. More in need of firearms than

cash, the gang burglarized the National Guard Armory in Ranger February 19,

1934. The date of the burglary differs in various accounts, but an Armory

break-in was reported in a February 20th issue of a Ranger newspaper,

making it likely that the burglary took place on the 19th. Too, the

formal charge specified the date of the crime as February 19th.

Thirteen .45-caliber Colt automatic pistols, four Browning automatic rifles,

and clips for the latter were taken. March 23rd issues of the Eastland

County News and The Loud Speaker reported that three men were arrested in

connection with the burglary, but investigations by Texas Rangers and

Ranger police determined that the real culprits were the Barrow gang. A

May 13th issue of The Ranger Daily Times reported that Clyde Barrow, Bonnie

Parker, Henry Methvin, Raymond Hamilton, and Hilton Bybee had been charged

with the crime. One source said that the Ranger Armory was one of several

armories hit by the Barrow gang.

On February 1, 1934, shortly before the Ranger burglary, the head of the

Texas prison system asked retired Texas Ranger Frank Hamer to assume the

new position of special investigator for the system. Hamer was specifically

assigned the task of tracking down the Barrow gang. Tipped off as to Bonnie

and Clyde’s whereabouts by gang member Henry Methvin, Hamer Methvin, Hamer

and FBI special agent. L.A. Kindell tracked them down to Methvin’s father’s

farm near Arcadia, Louisiana. They set up an ambush at Gibsland, Louisiana,

near the farm. On May 23rd, Bonnie and Clyde, traveling by themselves, were

killed by a posse in a barrage of bullets.

Raymond Hamilton, who had left the Barrow gang, was caught in April 1934

when he and an accomplice robbed a bank in Lewisville, Denton County, Texas.

Henry Methvin was eventually captured and sentenced to 15 months in prison.

However, he was later pardoned for having tipped off authorities about

Bonnie and Clyde’s whereabouts. In September 1935, though, he was convicted

of a murder in Oklahoma and sentenced to die in the electric chair. Hilton

Bybee was sentenced to 90 days in prison.

The National Guard Armory in Ranger was just north of the Masonic Lodge

building on South Rusk Street in what had been the Liberty Theater when it

was built in 1920. A lightening strike in 1990 destroyed the building. The

Carl Barnes Post no. 69 of the American Legion, organized in 1923, had

sponsored and helped organize Ranger’s National Guard. Some rifles belonging

to the American Legion Rifle Club were in the Armory at the time of the

burglary, but they were bypassed.

The Barrow gang’s exploits were the subject of several movies, perhaps most

notably Bonnie and Clyde (1967) starring Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway. The

gang was the topic of many articles and several books. Among the books was

Winston G. Ramsey’s On the Trail of Bonnie & Clyde, originally issued in

London, England in 2003 by After the Battle (Battle of Britain International

Ltd.) in its “Then and Now” series. Jeane Pruett, President of the Ranger

Historical Preservation Society, contributed the story of Ranger’s experience

with the Barrow gang to the book. Thanks to Mac Jacoby for supplying some of

the information on which this article was based.

T.E. Temple Peters

BONNIE & CLYDE - The famous, the not-so-famous, and the infamous:

visitors to Ranger and passers-through usually fit into one of these

categories. Probably no one fit better in the “infamous” category

than Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow. They met in 1930 but were

separated when Clyde went to prison on burglary charges. He escaped

but was recaptured a short time afterwards and sentenced to 14 years

in the state penitentiary. He was paroled in 1932, and he and Bonnie

reunited.

With other members, including Clyde’s brother Buck, the Barrow gang,

as it began to be called, committed a series of holdups throughout a

several state area—banks, filling stations, restaurants, in short any

place that might have some cash available for the taking. In the course

of their holdups and escapes, they murdered at least 13 people (sources1

differ as to the exact number) including law officers. Buck was killed

in one of the escapades. The Barrow gang’s exploits over a little more

than two years made national headlines. One writer pointed out that in

a way, the Barrow gang provided entertainment for a nation in the throes

of the Great Depression.

In January 1934 the gang made a daring and successful attack on a Texas

prison, freeing convicted bank robber Raymond Hamilton, who had been a

member of the gang before he was caught and imprisoned. They also freed

Henry Methvin, and he joined up. Members of the gang came and went, the

latter sometimes as a result of quarreling among themselves. At some

point Hilton Bybee joined the group.

Fresh from successful robberies in several states, the Barrow gang came

to Texas, Bonnie and Clyde’s home state. More in need of firearms than

cash, the gang burglarized the National Guard Armory in Ranger February 19,

1934. The date of the burglary differs in various accounts, but an Armory

break-in was reported in a February 20th issue of a Ranger newspaper,

making it likely that the burglary took place on the 19th. Too, the

formal charge specified the date of the crime as February 19th.

Thirteen .45-caliber Colt automatic pistols, four Browning automatic rifles,

and clips for the latter were taken. March 23rd issues of the Eastland

County News and The Loud Speaker reported that three men were arrested in

connection with the burglary, but investigations by Texas Rangers and

Ranger police determined that the real culprits were the Barrow gang. A

May 13th issue of The Ranger Daily Times reported that Clyde Barrow, Bonnie

Parker, Henry Methvin, Raymond Hamilton, and Hilton Bybee had been charged

with the crime. One source said that the Ranger Armory was one of several

armories hit by the Barrow gang.

On February 1, 1934, shortly before the Ranger burglary, the head of the

Texas prison system asked retired Texas Ranger Frank Hamer to assume the

new position of special investigator for the system. Hamer was specifically

assigned the task of tracking down the Barrow gang. Tipped off as to Bonnie

and Clyde’s whereabouts by gang member Henry Methvin, Hamer Methvin, Hamer

and FBI special agent. L.A. Kindell tracked them down to Methvin’s father’s

farm near Arcadia, Louisiana. They set up an ambush at Gibsland, Louisiana,

near the farm. On May 23rd, Bonnie and Clyde, traveling by themselves, were

killed by a posse in a barrage of bullets.

Raymond Hamilton, who had left the Barrow gang, was caught in April 1934

when he and an accomplice robbed a bank in Lewisville, Denton County, Texas.

Henry Methvin was eventually captured and sentenced to 15 months in prison.

However, he was later pardoned for having tipped off authorities about

Bonnie and Clyde’s whereabouts. In September 1935, though, he was convicted

of a murder in Oklahoma and sentenced to die in the electric chair. Hilton

Bybee was sentenced to 90 days in prison.

The National Guard Armory in Ranger was just north of the Masonic Lodge

building on South Rusk Street in what had been the Liberty Theater when it

was built in 1920. A lightening strike in 1990 destroyed the building. The

Carl Barnes Post no. 69 of the American Legion, organized in 1923, had

sponsored and helped organize Ranger’s National Guard. Some rifles belonging

to the American Legion Rifle Club were in the Armory at the time of the

burglary, but they were bypassed.

The Barrow gang’s exploits were the subject of several movies, perhaps most

notably Bonnie and Clyde (1967) starring Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway. The

gang was the topic of many articles and several books. Among the books was

Winston G. Ramsey’s On the Trail of Bonnie & Clyde, originally issued in

London, England in 2003 by After the Battle (Battle of Britain International

Ltd.) in its “Then and Now” series. Jeane Pruett, President of the Ranger

Historical Preservation Society, contributed the story of Ranger’s experience

with the Barrow gang to the book. Thanks to Mac Jacoby for supplying some of

the information on which this article was based.

RECREATION BUILDING - Like the rest of the nation, Ranger suffered during

the Great Depression, especially in the number of people unemployed. Several

New Deal public assistance programs were established, among them the Civil

Works Administration and the Works Progress Administration.

During its short life of November 1933 through March 1934, in addition to

other projects the CWA funded labor for construction jobs, mainly for public

buildings. Early in 1934 a committee of three from the Ranger Chamber of

Commerce and three from the Ranger Independent School District put together

a proposal for CWA funding for a combined municipal auditorium/gymnasium.

R.F. Holloway, superintendent of schools, was the major force behind the

proposal.

Some sources incorrectly describe what came to be called the recreation

building as a WPA project, but the WPA was not established until April 1935,

over a year after a newspaper article announced CWA funding for the project.

The article acknowledged that without CWA funding, the project would be

almost impossible to do.

The CWA approved the committee’s proposal very quickly, and it was announced

that work would begin immediately. The CWA ended up funding between $11,000

and $12,000 for labor. A bond issue for $5,000 to $6,000 to buy some

materials passed. Not many additional materials were needed. The three-

story Tiffin elementary school had been demolished in 1933, and the bricks

were stacked and saved in anticipation that they could be used for an

eventual municipal auditorium/gymnasium.

Tiffin, about four miles northeast of Ranger, had started out as a switch

station on the Texas & Pacific Railroad. Its population had grown to about

1,000 during the oil boom, but after the boom, population declined sharply.

After the Ranger Independent School District incorporated the elementary

school in Tiffin into the RISD and Tiffin students started coming to Ranger,

the school building was no longer needed.

In addition to the auditorium and gymnasium, plans called for the building

to provide an armory for the local National Guard unit, a cafeteria, a

school tax office, the administrative offices for the high school and

junior college (at that time the junior college was on the top floor of

the high school building), two apartments, and a club room. William

Bourdeau, a Ranger builder/general contractor, was project superintendent.

The building was designed by Fred Wilson, a carpenter with architectural

skills who worked for Bourdeau. The location was the northwest corner

of South Marston and Pine Streets, across the street to the north from

the high school.

In a 1993 interview Bill Bourdeau, who had worked with his father on the

building, reminisced how the building came to be called the recreation

building. The sign originally read “Ranger High School gymnasium,” but

the government inspector said that the name was unacceptable, since the

building had to be for the entire community according to CWA guidelines.

Thus the name was changed to “Ranger recreation building.” Bourdeau

recalled that he and his dad had worked at nights sanding the floor in

order for the high school class of 1934 to be able to graduate in the

building.

The recreation building did not have all the features in the original

plans. An apartment on the second floor at the rear of the building

served as a residence for the football coach. There was space for 600

people to sit on the playing court for events on the stage, and the

balcony could hold 500. The school tax office and the office of the

RISD superintendent of schools have been in the building in the fairly

recent past.

The recreation building has long served as a venue for basketball games,

physical education classes when the high school was across the street,

voting, fundraisers, pep rallies, etc. Every two years the Ranger Ex-

Students Association holds Ranger Homecoming events in the recreation

building. For over 80 years it has been an integral part of Ranger’s

community life.

RECREATION BUILDING - Like the rest of the nation, Ranger suffered during

the Great Depression, especially in the number of people unemployed. Several

New Deal public assistance programs were established, among them the Civil

Works Administration and the Works Progress Administration.

During its short life of November 1933 through March 1934, in addition to

other projects the CWA funded labor for construction jobs, mainly for public

buildings. Early in 1934 a committee of three from the Ranger Chamber of

Commerce and three from the Ranger Independent School District put together

a proposal for CWA funding for a combined municipal auditorium/gymnasium.

R.F. Holloway, superintendent of schools, was the major force behind the

proposal.

Some sources incorrectly describe what came to be called the recreation

building as a WPA project, but the WPA was not established until April 1935,

over a year after a newspaper article announced CWA funding for the project.

The article acknowledged that without CWA funding, the project would be

almost impossible to do.

The CWA approved the committee’s proposal very quickly, and it was announced

that work would begin immediately. The CWA ended up funding between $11,000

and $12,000 for labor. A bond issue for $5,000 to $6,000 to buy some

materials passed. Not many additional materials were needed. The three-

story Tiffin elementary school had been demolished in 1933, and the bricks

were stacked and saved in anticipation that they could be used for an

eventual municipal auditorium/gymnasium.

Tiffin, about four miles northeast of Ranger, had started out as a switch

station on the Texas & Pacific Railroad. Its population had grown to about

1,000 during the oil boom, but after the boom, population declined sharply.

After the Ranger Independent School District incorporated the elementary

school in Tiffin into the RISD and Tiffin students started coming to Ranger,

the school building was no longer needed.

In addition to the auditorium and gymnasium, plans called for the building

to provide an armory for the local National Guard unit, a cafeteria, a

school tax office, the administrative offices for the high school and

junior college (at that time the junior college was on the top floor of

the high school building), two apartments, and a club room. William

Bourdeau, a Ranger builder/general contractor, was project superintendent.

The building was designed by Fred Wilson, a carpenter with architectural

skills who worked for Bourdeau. The location was the northwest corner

of South Marston and Pine Streets, across the street to the north from

the high school.

In a 1993 interview Bill Bourdeau, who had worked with his father on the

building, reminisced how the building came to be called the recreation

building. The sign originally read “Ranger High School gymnasium,” but

the government inspector said that the name was unacceptable, since the

building had to be for the entire community according to CWA guidelines.

Thus the name was changed to “Ranger recreation building.” Bourdeau

recalled that he and his dad had worked at nights sanding the floor in

order for the high school class of 1934 to be able to graduate in the

building.

The recreation building did not have all the features in the original

plans. An apartment on the second floor at the rear of the building

served as a residence for the football coach. There was space for 600

people to sit on the playing court for events on the stage, and the

balcony could hold 500. The school tax office and the office of the

RISD superintendent of schools have been in the building in the fairly

recent past.

The recreation building has long served as a venue for basketball games,

physical education classes when the high school was across the street,

voting, fundraisers, pep rallies, etc. Every two years the Ranger Ex-

Students Association holds Ranger Homecoming events in the recreation

building. For over 80 years it has been an integral part of Ranger’s

community life.

Recreation Building in the late 30s

RANGER HIGH SCHOOL - A two-story frame building opening for the first

time for the 1886/87 school year housed all grades. In 1905 a two-

story, six-room red brick building was built that housed only high

school students. It was the first building known as “Ranger High

School.”

Some nearby communities which had only elementary schools, among them

Russell’s Creek, Lone Cedar, and Tiffin, sent high school students to

Ranger. Some high school students came to Ranger from farther afield.

M.H. Hagaman, early teacher and school superintendent, commented that

some out-of-town families sent their high-school-age students to Ranger

for schooling because of the quality of the high school education Ranger

offered. They boarded with local families.

Walter Prescott Webb, an early graduate of Ranger High School, recalled

those early high school classes many years later. They were, he said, a

mixture of the most unsophisticated country kids one could imagine and

sophisticated city kids: boys who knew how to wear a white collar and

the most charming girls, with bows in their hair and buckles on their

shoes.

Ranger’s school population burgeoned during the oil boom, making it

necessary to hold half-day school sessions, even with the hurried

construction of some temporary buildings. Planning for a massive

construction program for a high school building and several elementary

school buildings began during the oil boom and was carried out over a

several-year period during and after the boom.

Bonds were voted in 1921 for the construction of a high school building,

but a collapse of the bond market delayed their sale until 1922. In

1922 a contract was signed for the construction of a $250,000 high

school building. The building was completed in spring of 1923. It

had not only classrooms but also a library, auditorium, gymnasium,

facilities for a radio station and motion picture projection, a

cafeteria, a manual training workshop, science laboratories, and

home economics rooms. It was located on South Marston Street, between

Pine and Elm Streets. One writer described it: “This superb building

reflected the latest architectural beauty and perfection.”

The building housed Ranger Junior College from the time of its first

session in the fall of 1926 until it moved in 1948 to what had been

Cooper Ward School. College classes were for the most part taught

on the third floor of the high school building. High school consisted

of grades nine through eleven until at some point a twelfth grade was

added. After the junior college moved out, junior high school, or

seventh and eighth grades, occupied the third floor.

In a 1929 newspaper article superintendent R. F.Holloway said that

there were about 550 high school students. There were 20 faculty

members and a school nurse. He pointed out that in addition to the

usual academic courses, music classes in the wind instruments, piano,

voice, and violin were taught. Latin and Spanish were taught, as

well as a course in “expression” (speech).

The 1924 volume of Touchdown, the high school yearbook, described

the special departments. The Commercial Department was the largest,

with 190 students enrolled. Courses in bookkeeping and stenography

(but not typing in the early days) were taught. The Manual Training

Department included both shop work and mechanical drawing instruction.

The Sewing Department was the oldest department, having been started

before the move into the new building. Each of the 30 girls in the

Domestic Science and Cooking Department had to prepare breakfast,

lunch, and dinner (“in grand style,” the yearbook said) in her home

for one week as well as cook 80 “practical dishes,” presumably in the

course of the year.

The same volume of Touchdown listed organizations: Glee Club, Music

Club, Boosters Club, Choral Club, Junior and Senior Literary Societies,

Tennis Club, Galvez Club (all the girls taking sewing), “R” Association,

Spanish Club, and Latin Club. The Ranger High School Band was organized

in 1924. It played with the Ranger Junior College Band after the junior

college moved into the building. Athletics consisted of football,

basketball, baseball, boxing and wrestling, track, and tennis. A

lighted football stadium seating 4,500 spectators was completed in

the mid-1930’s. Adjoining the stadium was a lighted baseball field.

Annual special events included the seniors’ play, the junior-senior

banquet, kid day (seniors dressed in children’s clothes), and a banquet

hosted by the Boosters Club. The Hi-Hub was the student newspaper.

Seniors issued a “senior class prophecy” and individual wills and

testaments for the yearbook. The following were named in the 1924

yearbook: Best All-Around Boy, Prettiest Girl, Best All-Around Girl,

and Most Popular Boy.

In the mid-70’s it was decided that it would be more economical to

build a new school facility, with all grades under the same roof,

rather than renovate all the aging buildings. The class of 1977

was the last class to graduate in the old high school building. The

new facility, on Highway 80 East, was ready in time for the class

of 1978 to graduate there. The old building was torn down beginning

in 1978.

Recreation Building in the late 30s

RANGER HIGH SCHOOL - A two-story frame building opening for the first

time for the 1886/87 school year housed all grades. In 1905 a two-

story, six-room red brick building was built that housed only high

school students. It was the first building known as “Ranger High

School.”

Some nearby communities which had only elementary schools, among them

Russell’s Creek, Lone Cedar, and Tiffin, sent high school students to

Ranger. Some high school students came to Ranger from farther afield.

M.H. Hagaman, early teacher and school superintendent, commented that

some out-of-town families sent their high-school-age students to Ranger

for schooling because of the quality of the high school education Ranger

offered. They boarded with local families.

Walter Prescott Webb, an early graduate of Ranger High School, recalled

those early high school classes many years later. They were, he said, a

mixture of the most unsophisticated country kids one could imagine and

sophisticated city kids: boys who knew how to wear a white collar and

the most charming girls, with bows in their hair and buckles on their

shoes.

Ranger’s school population burgeoned during the oil boom, making it

necessary to hold half-day school sessions, even with the hurried

construction of some temporary buildings. Planning for a massive

construction program for a high school building and several elementary

school buildings began during the oil boom and was carried out over a

several-year period during and after the boom.

Bonds were voted in 1921 for the construction of a high school building,

but a collapse of the bond market delayed their sale until 1922. In

1922 a contract was signed for the construction of a $250,000 high

school building. The building was completed in spring of 1923. It

had not only classrooms but also a library, auditorium, gymnasium,

facilities for a radio station and motion picture projection, a

cafeteria, a manual training workshop, science laboratories, and

home economics rooms. It was located on South Marston Street, between

Pine and Elm Streets. One writer described it: “This superb building

reflected the latest architectural beauty and perfection.”

The building housed Ranger Junior College from the time of its first

session in the fall of 1926 until it moved in 1948 to what had been

Cooper Ward School. College classes were for the most part taught

on the third floor of the high school building. High school consisted

of grades nine through eleven until at some point a twelfth grade was

added. After the junior college moved out, junior high school, or

seventh and eighth grades, occupied the third floor.

In a 1929 newspaper article superintendent R. F.Holloway said that

there were about 550 high school students. There were 20 faculty

members and a school nurse. He pointed out that in addition to the

usual academic courses, music classes in the wind instruments, piano,

voice, and violin were taught. Latin and Spanish were taught, as

well as a course in “expression” (speech).

The 1924 volume of Touchdown, the high school yearbook, described

the special departments. The Commercial Department was the largest,

with 190 students enrolled. Courses in bookkeeping and stenography

(but not typing in the early days) were taught. The Manual Training

Department included both shop work and mechanical drawing instruction.

The Sewing Department was the oldest department, having been started

before the move into the new building. Each of the 30 girls in the

Domestic Science and Cooking Department had to prepare breakfast,

lunch, and dinner (“in grand style,” the yearbook said) in her home

for one week as well as cook 80 “practical dishes,” presumably in the

course of the year.

The same volume of Touchdown listed organizations: Glee Club, Music

Club, Boosters Club, Choral Club, Junior and Senior Literary Societies,

Tennis Club, Galvez Club (all the girls taking sewing), “R” Association,

Spanish Club, and Latin Club. The Ranger High School Band was organized

in 1924. It played with the Ranger Junior College Band after the junior

college moved into the building. Athletics consisted of football,

basketball, baseball, boxing and wrestling, track, and tennis. A

lighted football stadium seating 4,500 spectators was completed in

the mid-1930’s. Adjoining the stadium was a lighted baseball field.

Annual special events included the seniors’ play, the junior-senior

banquet, kid day (seniors dressed in children’s clothes), and a banquet

hosted by the Boosters Club. The Hi-Hub was the student newspaper.

Seniors issued a “senior class prophecy” and individual wills and

testaments for the yearbook. The following were named in the 1924

yearbook: Best All-Around Boy, Prettiest Girl, Best All-Around Girl,

and Most Popular Boy.

In the mid-70’s it was decided that it would be more economical to

build a new school facility, with all grades under the same roof,

rather than renovate all the aging buildings. The class of 1977

was the last class to graduate in the old high school building. The

new facility, on Highway 80 East, was ready in time for the class

of 1978 to graduate there. The old building was torn down beginning

in 1978.

TRAIN ROBBERY - trains began to flourish in the United States in the

nineteenth century, especially with the development of the American

West. With the advent of the train came a new category of crime:

train robberies. Newspapers had many accounts of train robberies

and attempted robberies. Trains carrying large sums of money, for

example, payrolls, were a major target. These shipments were

guarded by an expressman, whose responsibility it was to guard

the express car.

The Texas & Pacific began operating through Ranger October 15, 1880.

Less than two years later, on the morning of April 21, 1882, Ranger

had a train robbery. Five men boarded the eastbound train from San

Francisco at Ranger carrying Winchester rifles and Colt revolvers.

The Austin Daily Statesman described the robbers as four beardless

youths dressed like cowboys and a stalwart man who looked like a

desperado and appeared to be the leader. Four of the robbers

captured the conductor, fireman, engineer, and brakeman and held

them captive alongside the engine. The presumed leader of the group

headed for the express car and demanded that the expressman open

the safe.

In the meantime a porter saw what was happening and ran to the

passenger car, where there were three Texas Rangers. The Rangers

had been riding the train for several weeks to serve as guards.

They opened fire on the robbers, who returned their fire. One of

the robbers was wounded (the newspaper account does not say how).

After everyone was outside, the robbers put the captured train

crew between them and the Rangers until they were able to escape.

None of the Rangers nor any of the train crew was injured other

than the telegraph operator, who had a minor injury on his hand

caused by a stray bullet. The express car was riddled with bullets.

The article in The Austin Daily Statesman said that less than $500

was taken from the express car. The same article speculated,

however, that a much larger haul was made and the railroad did

not want the public to know the extent of the loss. Neither the

mail nor any passengers were disturbed, thanks largely to the

action of the Rangers.

Five days later the Rangers and other pursuers captured three of

the robbers. Railroad officials had claimed to know their identities.

The wounded member of the group had been captured two days earlier.

The general manager of Texas & Pacific had announced a reward of

$1,000 for the capture and conviction of the robbers. Later accounts

reported that all the robbers had been captured and sent to the

state penitentiary, where one of them eventually died.

WALTER PRESCOTT WEBB - Over the years Ranger High School has had

many alumni who have gone on to distinguished careers in the profes-

sions, other employment, and/or service in the armed forces. One such

alumnus is Walter Prescott Webb, who earned a teaching certificate

in the class of 1906. He went on to become a well-known historian,

writer, and long-time member of the history faculty at the University

of Texas.

Years after he had gotten his teaching certificate, he reminisced

about school days in Ranger. He recalled J. E. Temple Peters, an

early teacher and head of the school system, as an extraordinary

teacher, one who had, Webb said, an almost mesmerizing effect on

his students.

Webb described those early Ranger High School classes as a mixture

of the most unsophisticated country kids one could imagine and

sophisticated city kids: boys who knew how to wear a white collar

and the most charming girls, with bows in their hair and buckles

on their shoes. Webb remembered kids’ principal amusement was to

watch the passenger trains go by. For real excitement they would

walk the Texas & Pacific railroad tracks to the 98-foot tall “high

trestle” in the hilly area northeast of town, and as a freight

train would slow down for the grade, the bolder boys would hop on

for a ride back to town.

Webb was born April 3, 1888 in Panola County, Texas, the son of

Casner P. and Mary Elizabeth (Kyle) Webb. Casner Webb was a part-

time schoolteacher and part-time farmer. From Panola County the

family moved first near Breckenridge and then nine miles northwest

of Ranger near the Stephens and Eastland county line. In 1905

the family moved to Ranger. Walter had no interest in farming,

and he and his father agreed that he would attend Ranger High

School long enough to earn a teaching certificate.

He taught at various small schools in Texas & eventually enrolled

in the University of Texas, from which he received a bachelor of

arts degree in 1915. Three years later he was invited to join

the history faculty at the University. He wrote his master’s

thesis on the Texas Rangers. It was developed into The Texas

Rangers : A Century of Frontier Defense (published in 1935) .

Webb wrote or edited more than twenty books. Among his best

known is The Great Plains (1931). On the basis of this book Webb

earned his Ph. D. from the University of Texas. The Social Science

Research Council named the book as “the most outstanding contribution

to American history since World War I.” Still another of his best

known books was The Great Frontier (1952).

Webb taught for a year each at the University of London and Oxford

University, England. He was acclaimed as a teacher both in England

and in the United States. His seminars at the University of Texas

on the Great Plains and the Great Frontier were highly popular.

In addition to teaching, he served as director of the Texas State

Historical Association. As director he expanded the coverage of

the Association’s Southwestern Historical Quarterly and initiated

a project to create an encyclopedia of Texas, published in 1952

as the Handbook of Texas. Greatly expanded, the Handbook now

exists in an online version.

Webb married Jane Elizabeth Oliphant. They had one daughter. After

his first wife’s death, he married Terrell (Dobbs) Maverick. Webb

died March 8, 1963 as the result of an automobile accident.

SALOONS & CABARETS - The Old Rock Saloon (also called the Rock

Saloon) was one of Ranger’s early businesses. In its location

near the train station, it was one of the first places incoming

train passengers saw. Thus it catered to train passengers and

crews, but it also served as a community center for Ranger: it

was a meeting place as well as somewhere people could go for

entertainment and liquor. The saloon was occasionally the scene

of altercations, including some gunfights, one in which two men

were killed. Sometime in the 1890’s Ranger voted to ban liquor,

and the Old Rock Saloon became a no-liquor restaurant.

The vote to ban liquor notwithstanding, it was still accessible,

all the more so with the coming of the oil boom in 1917. Saloons,

bars, nightclubs, and cabarets flourished, and along with them

gambling places and houses of prostitution. Boyce House, an

early reporter and editor of The Ranger Daily Times, described a

typical cabaret as a bar and dance hall downstairs, with gambling

upstairs. Saloons might provide some or all of the enticements

of a cabaret but would have the more down-to-earth title “saloon.”

Virtually all such establishments had colorful names: for example,

the Blue Mouse Cabaret, the Grizzly Bear, the Winter Garden, the

Gusher, the Bucket of Blood (also called the Bloody Bucket), and

the Oklahoma Cabaret.

Larry Smits, who succeeded Hamilton Wright to become the second

editor of The Ranger Daily Times in 1919, reported that the police

chief had said that out of an estimated population of 25,000, he

figured that 1,200 were hustlers. Smits in particular noted

expensively dressed women who had on boots to the knee. They

would, he said, slog through the mud to the Winter Garden and

there change into dancing slippers “for the evening’s pleasure,

not unmixed with business.” An “entertainer” at a customer’s

table might receive a dollar tip for a song but sometimes did

much better. Some of the “entertainers” would earn as much as

$200 a week—if not quite a bit more.

Smits said that while some customers were content with cheap

corn whiskey, others had more expensive tastes: he remembered

one man in particular who ordered a quart of Canadian Club,

fresh from Juárez, for which he paid $50. Liquor was not the

only moneymaker. According to the Works Progress Administration

papers (Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, University

of Texas), Ranger gambling halls did a business equal to that

of the wildest days of the Klondike.

According to Boyce House, the Oklahoma Cabaret was the scene

of one of the most daring crimes during the boom. Two or three

men (accounts differ as to how many) entered the cabaret in

broad daylight, lined up a dozen customers at the bar, and

relieved them of their money. One source said the robbers got

about $10,000 in cash and a ring worth $2,000 belonging to the

proprietor. A policeman entered about that time, but the

robbers disarmed him. However, they were soon captured by

pursuers after a running gunfight in the street.

After Ranger incorporated in 1919, a local option election made

liquor illegal (again). Nonetheless it continued to be available,

even with the coming of National Prohibition in 1920. Speakeasies,

or places where liquor was illegally sold, abounded. In 1922 in

response to angry citizens, Texas Rangers seized liquor wherever

it was available. A group of citizens poured the liquor, worth

an estimated $16,000, into the streets. Why the closing of

saloons and other such places occurred so long after liquor

became illegal was a matter of speculation. In many oil boom

towns it was thought, sometimes with justification, that police

were involved in bribery and bootlegging.

Even after incorporation and Ranger had its own police force, it

was more often than not the Texas Rangers rather than the police

who were involved in law and order efforts. For example, in 1921

the Rangers and not the police raided the Commercial Hotel, famous

all over the area for its saloon and gambling operation, and

arrested 87 gamblers and seized gambling paraphernalia.

In the meantime Larry Smits, who first as a reporter and then

editor of The Ranger Daily Times, had seen much of Ranger’s

lawlessness. He commented: “I was in Ranger several months

before I knew there were real and reputable people raising

families, attending church, and perhaps making money honestly.”

After the boom Smits left Ranger, eventually ending up in New

York City. A successor at the Times said that Smits became

bored after most of the lawlessness was under control and

wanted to move on to a place that offered more excitement.

RANGER'S PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH - was organized in 1892 by a small

group meeting in the Methodist Church. It likely continued to

meet in the Methodist Church until it had its own building, but

it may also have met temporarily in a building on Tiffin Road,

according to a newspaper article. Rev. A.J. Burgess was the

first pastor, followed by Rev. W.A. Clack. George Bohning, W.

H. Hilliard, Joe W. Barber, and V.V. Cooper were the first

elders.

By 1894 the Presbyterian Church had built its own building on

the northwest corner of Walnut and Marston Streets, across from

the eventual location of the First Baptist Church. The cupola

and belfry were added in 1908. A newspaper article remarked

that these additions added to the looks of the building and

gave it a finished and church-like appearance.

The Ranger Church was initially affiliated with the Cumberland

Presbyterian Church, one of several denominations of the larger

church. The Presbyterian Historical Society (Philadelphia)

refers to the various “denominations” rather than “divisions”

or ‘branches.” A number of Presbyterian denominations developed

over the years. The nineteenth century especially was character-

ized by disagreements and division over theology, governance,

and the slavery issue. Among the several denominations were

splits, mergers, and reunifications, continuing on into the

twentieth century.

In 1903 the denomination called the Presbyterian Church in the

United States of America proposed a reunification with the

Cumberland Presbyterian Church. At the 1906 General Assembly

of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America, a

significant majority voted for the reunification.

As a result, in that year many Cumberland Presbyterian Church

congregations in Texas voted to affiliate with the Presbyterian

Church in the United States of America. The next year the Ranger

church split, with a majority of the congregation voting to

affiliate with the latter denomination and others voting to

remain on the rolls of the Cumberland Presbyterian Church,

which had not gone away as a result of the General Assembly

vote.

The Cumberland Presbyterian Church of Ranger was dissolved in

1921, and the First Presbyterian Church of Ranger, the name of

the church after a majority had voted to affiliate with the

Presbyterian Church in the United States of America, was

dissolved in 1952. After the final dissolution, the building

was converted into a private dwelling. (Photo courtesy of

the Ranger Historical Preservation Society)

TRAIN ROBBERY - trains began to flourish in the United States in the

nineteenth century, especially with the development of the American

West. With the advent of the train came a new category of crime:

train robberies. Newspapers had many accounts of train robberies

and attempted robberies. Trains carrying large sums of money, for

example, payrolls, were a major target. These shipments were

guarded by an expressman, whose responsibility it was to guard

the express car.

The Texas & Pacific began operating through Ranger October 15, 1880.

Less than two years later, on the morning of April 21, 1882, Ranger

had a train robbery. Five men boarded the eastbound train from San

Francisco at Ranger carrying Winchester rifles and Colt revolvers.

The Austin Daily Statesman described the robbers as four beardless

youths dressed like cowboys and a stalwart man who looked like a

desperado and appeared to be the leader. Four of the robbers

captured the conductor, fireman, engineer, and brakeman and held

them captive alongside the engine. The presumed leader of the group

headed for the express car and demanded that the expressman open

the safe.

In the meantime a porter saw what was happening and ran to the

passenger car, where there were three Texas Rangers. The Rangers

had been riding the train for several weeks to serve as guards.

They opened fire on the robbers, who returned their fire. One of

the robbers was wounded (the newspaper account does not say how).

After everyone was outside, the robbers put the captured train

crew between them and the Rangers until they were able to escape.

None of the Rangers nor any of the train crew was injured other

than the telegraph operator, who had a minor injury on his hand

caused by a stray bullet. The express car was riddled with bullets.

The article in The Austin Daily Statesman said that less than $500

was taken from the express car. The same article speculated,

however, that a much larger haul was made and the railroad did

not want the public to know the extent of the loss. Neither the

mail nor any passengers were disturbed, thanks largely to the

action of the Rangers.

Five days later the Rangers and other pursuers captured three of

the robbers. Railroad officials had claimed to know their identities.

The wounded member of the group had been captured two days earlier.

The general manager of Texas & Pacific had announced a reward of

$1,000 for the capture and conviction of the robbers. Later accounts

reported that all the robbers had been captured and sent to the

state penitentiary, where one of them eventually died.

WALTER PRESCOTT WEBB - Over the years Ranger High School has had

many alumni who have gone on to distinguished careers in the profes-

sions, other employment, and/or service in the armed forces. One such

alumnus is Walter Prescott Webb, who earned a teaching certificate

in the class of 1906. He went on to become a well-known historian,

writer, and long-time member of the history faculty at the University

of Texas.

Years after he had gotten his teaching certificate, he reminisced

about school days in Ranger. He recalled J. E. Temple Peters, an

early teacher and head of the school system, as an extraordinary

teacher, one who had, Webb said, an almost mesmerizing effect on

his students.

Webb described those early Ranger High School classes as a mixture

of the most unsophisticated country kids one could imagine and

sophisticated city kids: boys who knew how to wear a white collar

and the most charming girls, with bows in their hair and buckles

on their shoes. Webb remembered kids’ principal amusement was to

watch the passenger trains go by. For real excitement they would

walk the Texas & Pacific railroad tracks to the 98-foot tall “high

trestle” in the hilly area northeast of town, and as a freight

train would slow down for the grade, the bolder boys would hop on

for a ride back to town.

Webb was born April 3, 1888 in Panola County, Texas, the son of

Casner P. and Mary Elizabeth (Kyle) Webb. Casner Webb was a part-

time schoolteacher and part-time farmer. From Panola County the

family moved first near Breckenridge and then nine miles northwest

of Ranger near the Stephens and Eastland county line. In 1905

the family moved to Ranger. Walter had no interest in farming,

and he and his father agreed that he would attend Ranger High

School long enough to earn a teaching certificate.

He taught at various small schools in Texas & eventually enrolled

in the University of Texas, from which he received a bachelor of

arts degree in 1915. Three years later he was invited to join

the history faculty at the University. He wrote his master’s

thesis on the Texas Rangers. It was developed into The Texas

Rangers : A Century of Frontier Defense (published in 1935) .

Webb wrote or edited more than twenty books. Among his best

known is The Great Plains (1931). On the basis of this book Webb

earned his Ph. D. from the University of Texas. The Social Science

Research Council named the book as “the most outstanding contribution

to American history since World War I.” Still another of his best

known books was The Great Frontier (1952).

Webb taught for a year each at the University of London and Oxford

University, England. He was acclaimed as a teacher both in England

and in the United States. His seminars at the University of Texas

on the Great Plains and the Great Frontier were highly popular.

In addition to teaching, he served as director of the Texas State

Historical Association. As director he expanded the coverage of

the Association’s Southwestern Historical Quarterly and initiated

a project to create an encyclopedia of Texas, published in 1952

as the Handbook of Texas. Greatly expanded, the Handbook now

exists in an online version.

Webb married Jane Elizabeth Oliphant. They had one daughter. After

his first wife’s death, he married Terrell (Dobbs) Maverick. Webb

died March 8, 1963 as the result of an automobile accident.

SALOONS & CABARETS - The Old Rock Saloon (also called the Rock

Saloon) was one of Ranger’s early businesses. In its location

near the train station, it was one of the first places incoming

train passengers saw. Thus it catered to train passengers and

crews, but it also served as a community center for Ranger: it

was a meeting place as well as somewhere people could go for

entertainment and liquor. The saloon was occasionally the scene

of altercations, including some gunfights, one in which two men

were killed. Sometime in the 1890’s Ranger voted to ban liquor,

and the Old Rock Saloon became a no-liquor restaurant.

The vote to ban liquor notwithstanding, it was still accessible,

all the more so with the coming of the oil boom in 1917. Saloons,

bars, nightclubs, and cabarets flourished, and along with them

gambling places and houses of prostitution. Boyce House, an

early reporter and editor of The Ranger Daily Times, described a

typical cabaret as a bar and dance hall downstairs, with gambling

upstairs. Saloons might provide some or all of the enticements

of a cabaret but would have the more down-to-earth title “saloon.”

Virtually all such establishments had colorful names: for example,

the Blue Mouse Cabaret, the Grizzly Bear, the Winter Garden, the

Gusher, the Bucket of Blood (also called the Bloody Bucket), and

the Oklahoma Cabaret.

Larry Smits, who succeeded Hamilton Wright to become the second

editor of The Ranger Daily Times in 1919, reported that the police

chief had said that out of an estimated population of 25,000, he

figured that 1,200 were hustlers. Smits in particular noted

expensively dressed women who had on boots to the knee. They

would, he said, slog through the mud to the Winter Garden and

there change into dancing slippers “for the evening’s pleasure,

not unmixed with business.” An “entertainer” at a customer’s

table might receive a dollar tip for a song but sometimes did

much better. Some of the “entertainers” would earn as much as

$200 a week—if not quite a bit more.

Smits said that while some customers were content with cheap

corn whiskey, others had more expensive tastes: he remembered

one man in particular who ordered a quart of Canadian Club,

fresh from Juárez, for which he paid $50. Liquor was not the

only moneymaker. According to the Works Progress Administration

papers (Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, University

of Texas), Ranger gambling halls did a business equal to that

of the wildest days of the Klondike.

According to Boyce House, the Oklahoma Cabaret was the scene

of one of the most daring crimes during the boom. Two or three

men (accounts differ as to how many) entered the cabaret in

broad daylight, lined up a dozen customers at the bar, and

relieved them of their money. One source said the robbers got

about $10,000 in cash and a ring worth $2,000 belonging to the

proprietor. A policeman entered about that time, but the

robbers disarmed him. However, they were soon captured by

pursuers after a running gunfight in the street.

After Ranger incorporated in 1919, a local option election made

liquor illegal (again). Nonetheless it continued to be available,

even with the coming of National Prohibition in 1920. Speakeasies,

or places where liquor was illegally sold, abounded. In 1922 in

response to angry citizens, Texas Rangers seized liquor wherever

it was available. A group of citizens poured the liquor, worth

an estimated $16,000, into the streets. Why the closing of

saloons and other such places occurred so long after liquor

became illegal was a matter of speculation. In many oil boom

towns it was thought, sometimes with justification, that police

were involved in bribery and bootlegging.

Even after incorporation and Ranger had its own police force, it

was more often than not the Texas Rangers rather than the police

who were involved in law and order efforts. For example, in 1921

the Rangers and not the police raided the Commercial Hotel, famous

all over the area for its saloon and gambling operation, and

arrested 87 gamblers and seized gambling paraphernalia.

In the meantime Larry Smits, who first as a reporter and then

editor of The Ranger Daily Times, had seen much of Ranger’s

lawlessness. He commented: “I was in Ranger several months

before I knew there were real and reputable people raising

families, attending church, and perhaps making money honestly.”

After the boom Smits left Ranger, eventually ending up in New

York City. A successor at the Times said that Smits became

bored after most of the lawlessness was under control and

wanted to move on to a place that offered more excitement.

RANGER'S PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH - was organized in 1892 by a small

group meeting in the Methodist Church. It likely continued to

meet in the Methodist Church until it had its own building, but

it may also have met temporarily in a building on Tiffin Road,

according to a newspaper article. Rev. A.J. Burgess was the

first pastor, followed by Rev. W.A. Clack. George Bohning, W.

H. Hilliard, Joe W. Barber, and V.V. Cooper were the first

elders.

By 1894 the Presbyterian Church had built its own building on

the northwest corner of Walnut and Marston Streets, across from

the eventual location of the First Baptist Church. The cupola

and belfry were added in 1908. A newspaper article remarked

that these additions added to the looks of the building and

gave it a finished and church-like appearance.

The Ranger Church was initially affiliated with the Cumberland

Presbyterian Church, one of several denominations of the larger

church. The Presbyterian Historical Society (Philadelphia)

refers to the various “denominations” rather than “divisions”

or ‘branches.” A number of Presbyterian denominations developed

over the years. The nineteenth century especially was character-

ized by disagreements and division over theology, governance,

and the slavery issue. Among the several denominations were

splits, mergers, and reunifications, continuing on into the

twentieth century.

In 1903 the denomination called the Presbyterian Church in the

United States of America proposed a reunification with the

Cumberland Presbyterian Church. At the 1906 General Assembly

of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America, a

significant majority voted for the reunification.

As a result, in that year many Cumberland Presbyterian Church

congregations in Texas voted to affiliate with the Presbyterian

Church in the United States of America. The next year the Ranger

church split, with a majority of the congregation voting to

affiliate with the latter denomination and others voting to

remain on the rolls of the Cumberland Presbyterian Church,

which had not gone away as a result of the General Assembly

vote.

The Cumberland Presbyterian Church of Ranger was dissolved in

1921, and the First Presbyterian Church of Ranger, the name of

the church after a majority had voted to affiliate with the

Presbyterian Church in the United States of America, was

dissolved in 1952. After the final dissolution, the building

was converted into a private dwelling. (Photo courtesy of

the Ranger Historical Preservation Society)

BYRON PARRISH - Crime of all descriptions seemed to be a given

with oil boomtowns, and Ranger was no exception. There were

murders (five in one 24-hour period), knifings, brawls,

prostitution, and gambling. Saloons and cabarets flourished,

and liquor was readily available. The job of policeman was

hard enough (one Ranger policeman said that on a particularly

memorable night he had been shot at 27 times), and the position

of Chief of Police was even more difficult.

Chiefs of police came and went with some frequency in those

days. The Ranger Daily Times reported that there were 16

chiefs of police within 47 months, from February 1919 to

January 1923. Toward the end of 1919, several months

after incorporation, Ranger was looking for Chief of Police

number five, and in Byron Parrish city officials were

convinced they had found someone who was up to the job.

Byron Bruce Parrish was born in Mason, Texas May 14, 1876.

(Some sources incorrectly refer to him as Brian Parrish.)

At age 14 he left home and roamed over the Southwest with

an itinerant piano tuner. Parrish may have even tuned

pianos during that period, according to one account. A

skilled marksman, he became a peace officer in various

places mostly along the Texas border. He worked for a

time as a personal bodyguard for a Texas governor.

By 1907 he was constable in Portales, New Mexico. In that

year he shot and killed a Roosevelt County deputy sheriff

who had tried to disarm him, claiming that Parrish had

been drinking on the job. Parrish was acquitted. He

served with the Texas Rangers but resigned to go to

Ranger during the oil boom to deal in real estate and

horses. He eventually became a deputy constable, in

which position he attracted the attention of the Ranger

City Council in its search for a Chief of Police.

In his book Were You in Ranger? Boyce House, early

reporter and editor of The Ranger Daily Times, described

Parrish when he accepted the position of Chief. “… A

powerful figure, six feet in height, and weighing 200

pounds. He wore a white shirt, a four-in-hand tie,

made-to-order boots—high heeled, with fancy stitched

design--and a big white hat with a clover leaf emblem

on each side. Gold pieces were used as cuff links

and as shirt studs. A larger gold piece formed a

stickpin.” House said that Parrish could juggle a

tin can with bullets until both his six guns were empty.

Parrish was officially pointed Chief of Police Nov. 12,

1919. He pledged that he would rid the city of gambling,

soliciting, “wide-open” cabarets, and gun-toting. He

promised, “I am going to make this town a Gehenna on

earth for pistol-toters and gunmen.” He said: “Soliciting

on the streets must stop. Hotels and rooming houses will

be run in a decent manner. Drinks are being sold that

are not soft drinks. The rough stuff in the cabarets

must stop.” Ranger’s City Manager and the Commissioner

for Fire and Police declared that Parrish had the City’s

unqualified support.

A few days after his appointment Parrish and some of his

men raided every cabaret in town and searched customers

for weapons. The Ranger Daily Times reported that large

crowds gathered outside cabarets to watch the raids.

Early in his tenure as Chief, Parrish had a run-in with

a man described as the “local crime lord and king of

Ranger’s underworld.” No shots were fired, but Parrish

pistol whipped him and told him to get out of town. He

obeyed and never returned. Thanks to this and Parrish’s

other early successful efforts against lawlessness, the

murder rate plummeted. Boyce House called him “the man

who tamed Ranger.”

In spite of his initial successes, Parrish fell out of

favor within a few weeks of his appointment as Chief of

Police. City officials contended that open gambling had

continued, even with Parrish’s closing of some gambling

venues. The Ranger Daily Times ran a series of articles

opposing Parrish. One claimed, for example, that Ranger

had gained a notorious reputation because of continued

open gambling under Parrish’s regime.

The same article asked, “Why does Parrish claim he wants

the cabarets closed, when he called a meeting of several

cabaret owners in his home and suggested that they secure

an attorney to obtain an injunction restraining county

officials from closing cabarets—and offered to help them

secure this injunction?” Enraged, Parrish retaliated by

putting the Times editor in jail for a few hours. In

January 1920 the City Council put Parrish on probation,

giving him 15 days to live up to his promise to close all

gambling places.

When the postmaster complained to Parrish that one of the

mailmen had unfairly been given a ticket for a traffic

violation, Parrish slapped the postmaster. Parrish whipped

a respected businessman with a wet rope over a disagreement.

These incidents angered the public, and they demanded

Parrish’s firing. It was claimed that these violent

outbursts and irrational fits of bad temper were caused

by heavy drinking.

There was widespread interest—far outside Ranger’s city

limits—in Ranger’s oil boom and its aftermath. In May

1920 a Haskell, Oklahoma newspaper ran a news item from

Ranger: Ranger’s Chief of Police Byron Parrish was

arrested by deputy sheriffs for running a whiskey still.

He claimed that he had been framed and that he was innocent.

After he was fired, he left Ranger, and the Assistant Chief,

Gene Reynolds, took his place.

Byron Parrish died in Rankin, Texas June 17, 1931. The

Associated Press reported that the cause of death was

“excessive use of alcohol.” He had been married multiple

times. He and his first wife, Annie Gertrude Hope, had

two children together: Byron Bruce (Buck J.) Parrish

(he later changed his surname to Hope), and Cleo Vernice

Parrish.

FIRST BAPTIST CHURCH - In the early 1880's and possibly

before then, a Rev. Hilliard led outdoor revivals in

Merriman, Texas, a few miles south of Ranger. These

revivals were well attended, drawing people not only

from Eastland County but also from neighboring counties.

Baptisms were in nearby Colony Creek. There was no church

in Merriman that converts could join (Merriman Baptist

Church was not founded until 1892), so Rev. Hilliard

issued certificates of baptism, and people could join

the church of their choice.

According to the First Baptist Church's Website, the

Church began meeting in 1881. A number of sources say

that the Church was organized after one of the revivals

in Merriman. The newly founded Church began meeting in

a school building, with congregants sitting on benches

with no backs. In 1885 the Church built a small frame

building on the corner of Walnut and North Austin Streets.

Several years later this site became unsatisfactory for

the Church, and the building was sold, with the buyer

converting it into a residence. Thereafter the Church

met for a time in Ray's Academy, on the corner of Mesquite

and Marston Streets.

The Academy building burned down, and the Church met

temporarily in the Methodist Church and then in the

Presbyterian Church. According to one source, the First

Baptist Church and Presbyterian Church possibly met on

alternate Sundays when they shared the same building.

About 1897 the First Baptist Church purchased a lot

from the T & P Railroad Company for $25 (some members

remembered that T & P donated half the cost of the lot).

The lot was south of the eventual location of the Gholson

Hotel and in the area that became the Hotel's parking

lot. A new building was built on the lot.

The Ladies Aid and other women and friends of the Church

(some are pictured here) served dinners and ice cream

suppers to raise money for the building fund. The

dinners, costing 25 cents each, became so popular that

railroad workers and even train passengers would buy them.

The location became increasingly unsuitable for the Church:

a cotton gin opened across the street, and a wagon yard

began operating on one side. In the meantime in 1915

the Church had bought two nearby lots for $250, planning

to build on that site. However, with the coming of the

oil boom in 1917, the two lots increased enormously in

value.

The Church had held off on building and was able to sell

the lots for about $50,000. During the oil boom the Church's

membership was about 750. With the proceeds from the sale

the Church was able to buy the lot at Walnut and North

Marston Streets in 1918 and begin building. Until the

building was completed in 1920 at a purported cost of

$100,000, the Church met under a tabernacle.

In the early 1920's a controversy in the Church arose

over the Ku Klux Klan. Some members supported the Klan

and resigned from the Church to form the Central Baptist

Church. One source reported that robed Klansmen at least

at one point marched down the aisles (the aisles of which

church is not clear). After the Klan's influence had

waned and the movement had died down, members who had

left rejoined the First Baptist Church.

In 1966 the Church dedicated a new sanctuary adjacent to

the 1920 building, and both the 1966 building and the 1920

building are still in use.

BYRON PARRISH - Crime of all descriptions seemed to be a given

with oil boomtowns, and Ranger was no exception. There were

murders (five in one 24-hour period), knifings, brawls,

prostitution, and gambling. Saloons and cabarets flourished,

and liquor was readily available. The job of policeman was

hard enough (one Ranger policeman said that on a particularly

memorable night he had been shot at 27 times), and the position

of Chief of Police was even more difficult.

Chiefs of police came and went with some frequency in those

days. The Ranger Daily Times reported that there were 16

chiefs of police within 47 months, from February 1919 to

January 1923. Toward the end of 1919, several months

after incorporation, Ranger was looking for Chief of Police

number five, and in Byron Parrish city officials were

convinced they had found someone who was up to the job.

Byron Bruce Parrish was born in Mason, Texas May 14, 1876.

(Some sources incorrectly refer to him as Brian Parrish.)

At age 14 he left home and roamed over the Southwest with

an itinerant piano tuner. Parrish may have even tuned

pianos during that period, according to one account. A

skilled marksman, he became a peace officer in various

places mostly along the Texas border. He worked for a

time as a personal bodyguard for a Texas governor.

By 1907 he was constable in Portales, New Mexico. In that

year he shot and killed a Roosevelt County deputy sheriff

who had tried to disarm him, claiming that Parrish had

been drinking on the job. Parrish was acquitted. He

served with the Texas Rangers but resigned to go to

Ranger during the oil boom to deal in real estate and

horses. He eventually became a deputy constable, in

which position he attracted the attention of the Ranger

City Council in its search for a Chief of Police.

In his book Were You in Ranger? Boyce House, early

reporter and editor of The Ranger Daily Times, described

Parrish when he accepted the position of Chief. “… A

powerful figure, six feet in height, and weighing 200

pounds. He wore a white shirt, a four-in-hand tie,

made-to-order boots—high heeled, with fancy stitched

design--and a big white hat with a clover leaf emblem

on each side. Gold pieces were used as cuff links