THE TROLL:

An Allegory for Easter

“I saw ya’ with a girl earlier, Golden Boy. Who was that? If I had her back here for one hour, I’d break all the laws uh’ nature an’...”

Harry vaulted over two

“Don’t move,” Corelli soothed into his right

ear from behind, simultaneously drawing a fine arc-crimson line, lightly, slowly

across Harry’s throat, accenting it with pauses; punctuation dots—a necklace of

tiny ruby beads emerged.

“...Or I’ll cut you from gizzard to Tuesday.

I just might do it anyway. It really don’t matter to

me.” The hot crowded railway car of recruits became a frozen diorama.

(1 Peter 5:8)

Then, just as quickly, Vinny released and just as smoothly, laughed at Harry and himself.

“Look kid, I didn’t know she was your sister

till Joe here just whispered it. Tell ya’ what kid, I won’t

say nothin like that ‘bout your sist...”

“Not about any girl,” Harry glared at him

with new steel blue eyes locking in piercing intensity.

“Ever again.” (Mat

Harry was completely self assured, in control

and oblivious to the recent encounter. Neither was hurt, though one had just

faced instant death. (Isaiah 41:10)

Vinny Corelli immediately sensed the calm

simple righteousness of it all. Perhaps the one quality he still respected was

basic truth and the truth of Harry’s position was inescapable. After all Vinny had not survived his seventeen years on

“You got it,” he responded.

That ended it.

All derision, all banter, all conversation

had ceased. Each recruit became caught up on his own world. A year form now

they might all be dead.

Vinny had experienced a catharsis. His life

had been a lie. He even lied about his age to get here. And now, when boldly

confronted with the liberty of real truth, he knew his life would not be the

same. (John 8:32)

Harry John Nordstrom thought only of Kristin.

His sister, at sixteen, was closing in on herself.

It was late August of 1942. This was a troop

train vacuuming new recruits from all over the

Harry John and Kristin Leah Nordstrom grew up

on a dairy farm outside Spring Green,

“God bless Great Aunt Maude,” Harry

thought.

Their great aunt Maude MacWatter lived in

“Kristin has met her but I haven’t,”

Harry reasoned. Then, he too became submersed in his own musings as he sat at

the back of the aisle on the floor.

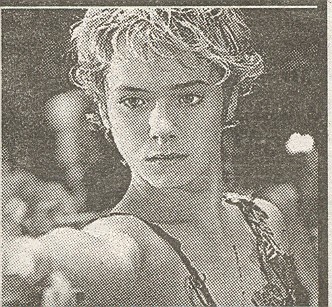

Kristin was up in the first railroad car and

even had a seat. She felt secure, surrounded by experienced MP’s assigned to

keep order enroute. Kristin Leah Nordstrom had always been a happy child,

vivacious and innocently effervescent, but no longer. No, she could feel a

change, a darker mood. “The only way I can ever come out of this is to focus

on Harry and our chance to be a family again,” she thought. The young MP’s

in her rail car left her alone, sensing that was what she needed most from

them. But their first sergeant sensed a different need from her—the need for a

father figure who was a good listener.

“My brother, Harry is back there,” she began.

“Harry always was—well, exceptional—in every way! It was kind of weird,” she

tapered off. “He only had one flaw, if one could call it that; he never could

stand to be alone unless it was on his own terms.”

“Which one is he?” asked the 1st

sergeant. “I’ve made several sweeps through the train for weapons shakedowns.

All the boys are still in civvies and I never noticed one younger boy in the

last car, though all the cars are crowded.”

“Oh, Harry was always big for his age! He blends right in with the older boys—except for his eyes,” she added softly. “There is something about his eyes.

“Well, it is certainly dark back

there; we found no weapons. Mot of those kids are just

a little older than he is, anyway.”

She started again, “Everything cam easy for

him—It really did! I remember, when he was a toddler, how he bubbled with each

new discovery and with the sheer joy of being alive. All Harry’s life, he

sparkled with quiet assurance in every new challenge.”

The 1st sergeant just nodded,

pensively, thinking of his own sixteen-year-old daughter and fourteen-year-old

son in

Kristin continued, brightening as she talked

about Harry. “Sergeant, it is almost like a whiff of magic that comes along

with Harry. Anyone’s best traits are somehow brought out for ever after!”

Enthusiastically, she continued, “Oh, maybe not noticeably, at first. But

eventually this is what always happens.”

“You

see, Harry has this people acumen and common sense wisdom far beyond his

years.”

The MP sergeant nodded, a bit puzzled. “Well I’m going to make rounds again with my next guard detail, just so I can meet Harry. That will be at 0300 hours.” And he got up for more coffee.

“I did not see him,” the 1st

sergeant said, upon returning. “But they were all asleep and it was

dark.” Kristin, too, was asleep and did not hear his report.

Even before conception, Harry John Nordstrom

had been richly blessed by the one true God he did not yet even know (PS

139:14).

This troop train had been moving south from

On this August night, as the train passed

through

“When the train stops here for coal and

mail, I’ll get off. Everyone is asleep and by the time Kristin realizes, maybe

she’ll be safely with Aunt Maude and I can contact them there. Kristin knows I

will be OK. This will be best for Vinny too. Maybe someday we’ll meet again.”

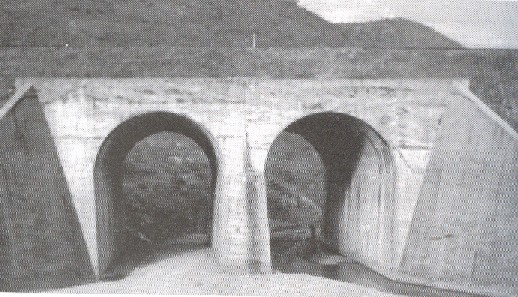

The train eased across Mooney’s bridge

trestle, then Buck’s bridge, with a long slow curve as

it entered the north end of the sleeping town. When it stopped, momentarily for

the switchman and main line clearance, Harry got off and disappeared into the

woods by

In DeSoto, multiple sets of tracks ran

straight, through a flat ancient valley carved by Joachim Creek which still

runs parallel to the tracks and the Main street. This had long been a railroad

town and had extensive car shops for new construction and repairs.

“Bonnie, there’s somethin’—or someone livin

under the ole stone bridge up the hill,” Billy Blue announced to his wife.

“The one the W.P.A. was gonna’ tear down?”

the other room queried.

“Yep,” Blue answered, “But then the war broke

out.” Pause. “I’m talkin bout the ole stone bridge up th’ hill to the west, up

in tha’ woods,” he gestured to no one.

Bonnie and Billy Blue lived at the end of

“It’s a boy,” Blue told her the very next

day.

“Prob’ly some young hobo, come up form a

freight train,” she said without looking up from her book. “Well, we gotta take

food up ther’ reg’lar till he moves on.”

“I’ll start takin’ food after supper

tonight,” Blue responded.

“Every night,” she got the last word. And

each evening, after dark, he climbed the path up the hill to the northwest and

set an army tray of food on a flat rock near the stone bridge tunnel. Blue

never nosed around. And he never saw anyone. For her part, Bonnie Blue was a

night owl who read incessantly; mysteries, mostly. All this was very real to

her and ordinary.

Harry, even in this gathering winter darkness

perceived quickly that Blue meant everything for his good. So Harry made

certain he was never around when Blue was. Harry learned early to follow the

milkman, lifting a pint and a half from a different porch each morning. “I’ll

keep a careful daily record and pay them back, soon,” Harry resolved. And he

did, later doubling the value of what he took.

Their dad had been a dairy farmer and

sometime stonemason. In no time, Harry had wedged loose stones, refitted a

lintel where there was none and rearranged other stones to build a small crawl

in room midway through the tunnel’s arched sidewall.

He used insulation and wood from wrecked

freight cars and when he finished, no one could tell he lived in the sidewall

of the tunnel. Of course, he was almost never there.

In his gray confines of yet another Autumn dawn Harry began the monologues.

“Loneliness is taking me apart. I’ve never

felt this empty, before.” “I am undone.” In complete despair and feeling

totally alone, he suffered. (PS 27:9)

Every night train sounded the same mournful

whistle as it rounded the slow curve over the bridge to enter the town from the

north. It was a melancholy prophetic sound, like people were going to die afar

off, somewhere and there was nothing Harry could do to stop it. “I hurt in my

heart and I don’t even know why,” his monologue continued.

After that, Harry thought of spending time

down at the hobo camp, but they had all gone. He sensed changes in himself. His

self-assurance and natural ease were disappearing. No longer was he someone

people gravitated towards or wanted to be around. He felt diminished, as if he

were becoming invisible. (PS 139:7-10) That may have been one reason why he

started playing when Ole’ Blue first brought the chess set and left it.

Harry even took to reminiscing in his

loneliness. He longed for the happy times when he played chess with dad and

when their mother, and English teacher, read to them from great literature. In

those times, he rode with Ivanhoe and improvised with Robinson Crusoe. But now,

he saw himself as another Caliban, more morose than Browning’s primeval

creature or even Shakespeare’s; trapped in the muck of his own thoughts and

decisions.

Out of loneliness Harry dressed up that

Halloween. He first noticed appearance changes then. He had started wearing

this long, oversized black overcoat and wide-brimmed floppy hat Bonnie had

sent. That Halloween, Harry prowled at the peripheral with the last of the

older kids, always at a distance, always stepping back in the dark as they

approached each house.

He noticed gray black hair had begun to grow

everywhere—even on his face and head. Without sunlight he began to smell musky

and there was a change in his voice; now deeper and rasping from non-use. With

his broken mirror he noticed the color of his eyes seemed to have changed form

azure blue to angry coal spots on his pale gaunt face.

“What is happening to me?” Harry lamented in

newly found rage and horror.

His behavior too was changing. At first he

only did acts of caring before daybreak like throwing papers up onto the porch.

But gradually even his harmless pranks became mean spirited like hiding left

out toys and tying tricycles up in trees. The idle loneliness and alienation of

his lifestyle were closing in. For the first time Harry was becoming bitter as

each long night merged into the next. Three was no light for Harry.

Young children throughout the north end

became increasingly more fearful of the gray phantom lurking out there,

somewhere in the woods. A group of draft-exempt neighborhood men formed a

committee to talk about going into the woods on night watches.

“Those gun crazy fools are talkin’ about

waylayin’ our boy,” Blue announced over dishes. (PS 59:1-2) “They’ll shoot at

any shadow of turnin’. Ther’s even some talk he’s a German spy here to count

new freight cars.”

“Can’t you coax him into comin’ in to stay

with us till Spring?” Bonnie pleaded, turning a page.

“Coax ‘im! I can’t even talk to ‘im! I never even seen ‘im. Not once, just a shadow sometimes,” Blue

complained into his coffee cup.

“Well, you take this warnin’ note with supper

for the next three nights,” Bonnie insisted. She had stopped reading, showing

increasingly grave concern.

Later from the other room:

“I thought we were finished with that white

sheet bus’ness ‘round here.”

Silence.

“Blue—they might hit our boy!”

“I know,” was all he said.

“Just for bein’ different,” he mumbled mostly

to himself.

Harry got the messages and became one of the

shadow people, skirting around the dark margins of the imagination, usually

unseen but to God.

Bonnie and ‘Ole Blue thought maybe he had

left town. Blue continued to study chess moves but there were no clear

indications Harry even looked at the chessboard, anymore. He left no tracks.

Meanwhile, the town vigilantes turned their

full attention to the German-American dairy owner. After all, he was very much

a reality and he still spoke with an accent. His name was Bergamann.

Another German-American was Erich

Stechbarger. Erich was a young father of five. He was a large, powerful man and

the town’s produce wholesaler. Erich drove to produce row’s Soulard Market six

late nights. He would leave town, driving north about

One early morning in January, just leaving

the town’s north end, too late, Erich thought he saw something “What is tha”...

He started to say but was unable to finish.

Too late, he stomped on his brakes as a black

movement flashed left to right across his headlights and he felt a light thump.

He had hit Harry, who was already moving off

into the brush by

“Hey!” Stechbarger yelled into the black.

“Stop right there.”

“Come back here.”

“Now!” The angry commands because Erich was afraid it would disappear.

Harry did come back. But he was hurt. Head

down; a sordid specter in gray and black.

“Take off that hat.”

“Look at me.”

“Are you hurt? Talk to me.”

Only then did Erich realize that this was a

boy and he had hit him with his truck.

Those were commands. Now Erich offered

compassion. “How can I help you?”

Harry seemed dazed, but after a pause—

“You can give me a job tryout,” Harry cheerfully

responded.

Quickly relieved, Erich answered, “OK. Do you

know anything about produce?”

“I’ve worked with farm produce my whole

life,” Harry responded quickly.

“That long!” Erich teased.

“OK, then, here’s what we’ll do. First, let

me look at that leg. Then I’m driving straight to an all night clinic I know in

the city.”

Erich kept his word. He had found his night

man and never asked any questions. Harry worked hard and never volunteered more

than his first name. For his part, Erich paid in cash and never told anyone

about his new helper. Good help was hard to find, the war and all.

Erich Stechbarger was, like ‘Ole Blue, the

right man, sent for times like these in Harry’s young life. Erich was a Godly

man, non-judgmental with wise counsel to offer when asked.

Meanwhile, Harry had been living at the rough

raw edges of reality in a place seemingly devoid of compassion and light except

for Bonnie, ‘Ole Blue and now Erich, his trusted mentor.

He missed his dad. There was a mighty

spiritual battle going on around him and within him. He could feel it. His time

apart from Erich was an empty and frightening time. All around, Harry felt the

presence of evil. At first it’s ubiquity seemed

curious, but, now...dismayed by the darkness and confused by the confines of

his lonely world, Harry seemed inexorably drifting into a despair—a kind of

despair from which there would be no returning. He became an enigma, even to

himself.

Out of the night Harry jumped aboard at the

city limits sign. Immediately, he became loquacious chattering non-stop. It was

March and Spring was coming on.

“Have you stayed up all night?” Erich asked,

trying to calm him down.

“Never mind that. I’m fine. We’re friends now aren’t we?”

“Sure what’s on your heart?” Erich answered

with a question and a calm leveling tone.

“I need a promise. Will you make sure they

play Nessun dorma at the end of my funeral? That’s from Puccini’s opera,

Turandot and I especially like the end of that song.

“Sure I will,” Erich quickly responded as he

slowed his truck to look over at Harry’s face: typical, mood-swings of the

young, he thought. The boy was already sleeping peacefully.

Very early on Easter Sunday morning, in total

frustration and self-loathing, Harry shaved his head, arms and legs. Then he

cleansed himself and put on new clothes he’d bought from savings and Erich had

picked up. He especially liked the light blue hooded sweatshirt.

All at once there was a bright light from up

on the old stone bridge.

“John. Come out,” a feminine voice gently

insisted, breaking the early dawn’s silence.

“Come. Up here.” A second

command.

“On the bridge.” Clearly and firmly this came. Then silence

again.

Suddenly humbled as never before, but still

curious, Harry looked around him. Gone were all traces of nefarious deep

darkness. He came out of his tunnel and climbed toward the light. Up on the

bridge he stared in fascination. His now clear blue eyes widened. Her white

garment glowed. She had a strange ethereal aura; at the same time puzzling and

reassuring.

“She looks so serene,” he thought, “So

joy-filled! So unlike anyone I have ever known.”

“Who... Who ARE you?” Harry-John

stammered.

“Whe... where did you come from?”

“H... How did you find me?”

She smiled.

“I am Gabrielle.”

“I came from Dayspring.”

“HE told me where to find you.”

“HE has been with you—all along.”

“You are blessed.”

“Come. I will take you to HIM,” she beckoned.

“But look at me. I can’t go with you,”

Harry-John protested vehemently.

She turned, the

caring smile again.

“HE wants you just as you are.”

She turned back towards him extending both

arms palms up, outstretched.

“With HIM—nothing is impossible.”

“Come.”

They followed the break up the hill northwest

and into the trees. Merry miniature waterfalls sparked in the early morning

sun.

“I never even knew this was here,” Harry-John

was amazed.

“For you it wasn’t...until now,” came the

reply.

They were completely away from the town now.

As they came closer, Gabrielle, in the lead, a figure in white approached them.

Harry could already feel the warmth of HIS healing power within. Harry walked

faster, this time focused with child-like awe. Harry-John felt suddenly

energized throughout his entire being.

“I know HIM!” he exclaimed and moved

ahead of her. She stopped and when he turned around to repeat it, she was gone.

Oh, there were still a few rumors of

sightings. Usually from the town drunk or the milkman, something about cash

found in his empty returnables—but they never saw him.

Harry was working the produce route full time

now to save money.

“Call me John, now. You know, like the one

whom Jesus loved,” Harry announced to Erich early one Spring

morning just after Easter Sunday.

“I’ll call you whatever you want,” Erich

bantered, “As long as you keep working so hard.” Erich Stechbarger had become

totally taken with his young helper and he had been mentoring him in all

matters, helping him to become a godly young man. Erich helped him send a

telegram to

John’s only telegram to his sister Kristin

was terse.

“New life for us both. STOP

Join you very soon. STOP

Love, forever, John.” STOP

“He scrubs up real nice don’t he?” Bonnie Blue commented to Ole’ Blue at the busy town station to see

John off. Of course, all she had ever seen of him was just the late

night shadow-of-turning by her window. As for Blue, he had never really seen

him either—not once. But when he went up to bring his chess set home, he could

easily see that he’d been checkmated! Ole’ Blue just smiled.

“Daddy he is—just beautiful, now. He almost

shines,” Erich’s youngest daughter exclaimed, vociferously. She especially

admired John’s thick blond curls and said so.

“That inner beauty was there all the time,

honey.” Erich Stechbarger gently answered, scooping up his daughter in his

powerful arms. “Even through the worst of it,” he added, almost to himself.

“But not until he met Day Spring was it this

clear and focused,” her mother answered, continuing “He has a certain

something—New,” she finished, with conviction.

¾¾¾¾¾¾¾¾¾¾¾¾¾¾¾¾¾¾¾¾¾¾¾¾¾¾¾¾¾¾¾¾¾¾¾¾

Do not forget to entertain strangers, for by

so doing, some have entertained angles—unawares.

¾Hebrews 13:2

¾¾¾

Through tender mercy of our God with which

the *Dayspring—from on high has visited us; to give light to those who sit in

darkness and the shadow of death.

¾Luke 1:78-79

*(literal translation—Dawn; the MESSIAH)

¾¾¾

For I know the plans I have for you, says the

Lord, plans of peace and not of evil, to give you a future and a hope.

¾Jeremiah 29:11

EPILOGUE

All we like sheep have gone astray; We have turned every one to his own way;

And the Lord has laid on Him the iniquity of

us all.

¾Isaiah 53:6

UNDER THE BRIDGE AT NO GUN RI

25 July

At No Gun Ri Korea, an estimated 400 Korean refugees were killed, massacred in cold blood. 83% were women, children and babies or men over age forty.

One

fourth of the dead (25%)

Were

babies or other children

UNDER

AGE TEN.

With machine guns set up at both ends of the eighty foot long twin tunnels—mostly green teenaged recruits, led by inexperienced officers, massacred with abandon.

The young lieutenants from occupied

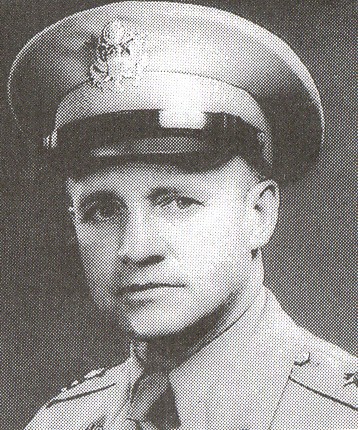

All were carrying out written orders of 1st

Calvary Division Commander,

Major General Hobart R. Gay

All

were Americans.

Harry John Nordstrom was there!