WILL THE CIRCLE BE UNBROKEN?

--Prologue to a Poem

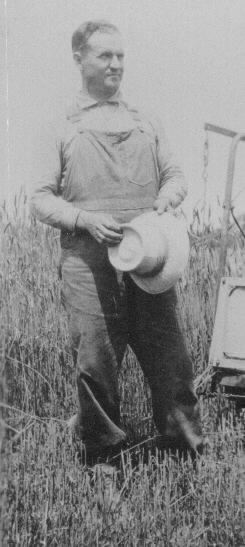

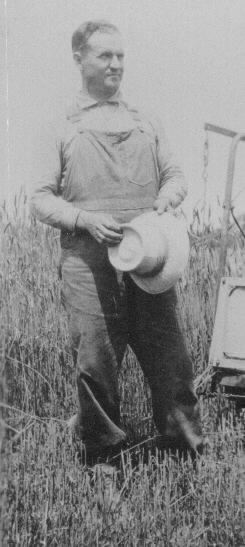

Elmer Joseph Vivrett

Elmer Joseph Vivrett

My dad was born on the old John D. Hearst River Farm near

Vineland, Missouri, in 1891 - - maybe. Maybe, because along about

then St. Joachim’s partially burned. All the parish records - - birth,

marriages, deaths, that were kept in the basement suffered water damage.

His church birth record was blurred and a civil record suggested 1888.

St. Joachim’s is still there, the parish for La Vielle Mine - - the old mine.

Old Mines was a village in Missouri French Country – representing just a

part of King Louis XIV’s grand dream of a new France. Descendants of

these two hundred French miners who arrived with Phillipe Francois Renault

in 1723 to mine lead are still there, scattered among the hills, south of

St. Louis.

St. Louis was a newcomer among French settlements.

Some of the first, like Cabanage a Renaudiere, about 1710, have long disappeared.

Others like Mine La Motte, 1714, at the origin of Big River, and a cluster

of communities in Washington County like Mine a Renault, 1724, and Vielles

(Old) Mines, 1726, are still there. The most famous village, of course,

was Ste. Genevieve, fondly nicknamed “Misere” – (Miserable) about 1722.

The Missouri French built their villages in clusters, since the Osage with

brazen impunity, would travel one hundred miles to steal a fine horse.

The land was divided into arps – a measure about 192’6” square. Each

lot was one arp wide but perhaps a mile deep. This close community

suited the social, fun-loving French an disgusted the first English and Americans,

reared in the glumness of their Puritan Ethic. The villagers were Catholic,

but less ardent than those in Canada or France. They practiced a frontier

religion in a frontier life. They were not lazy, but easy going and

gregarious. They enjoyed themselves much more that their American counterparts.

There was no brutality of man against man in those early days; no evidence

of a single duel among these villagers. The most common crime was horse

theft, and that was usually by Indians. They saw nothing wrong in dancing

on Sunday. In fact, Sunday was for celebrations; one ball in the afternoon

for children and another Sunday night for the adults. The men would

work in the mines and fields Monday and Tuesday from dawn till dark to get

enough work done by Wednesday noon so they wouldn’t have to return o work

till the next Monday. These extra long weekends they would play cards,

sing, dance, and tell tall tales. But these were a genteel people,

with elegant manners. The wives were treated as full partners and slaves

were usually treated as members of the family. Sometimes the balls

would last two or three days. The slaves and Indians were always invited

- - and they came. The early Missouri French hardly knew the meaning

of the word prejudice. Rough frontier travelers of the middle valley

were astounded to find imported silk, satin, velvet and silver; in this wilderness,

a genteel, compact civilization.

In the 1760’s, rather than offer allegiance to the despised

George III and England, scores of Kaskaki’s residents were persuaded

by young Auguste Chouteau to leave home and move to the west bank to occupy

his new village called St. Louis. A secret treaty in 1764 put this

land under the Spanish Crown but any government was better than the British

government. Thus it should be no surprise to anyone that the Missouri

French sided with colonist in the American Revolution. They preferred

the crude, uncultured, often lawless Americans for neighbors rather than

the British. They were probably unaware that the new American nation

had unfinished business: slavery still existed, Catholics still suffered

discrimination and women were denied equality. With their creed of

tolerance, the Missouri French would have found their new neighbors’ prejudices

hard to accept. For their part, the Americans, who regarded shooting

Indians as somewhat akin to squirrel hunting, did cause the marauding Osage

to retreat to Western Missouri. The Americans were much better farmers

and the Missouri French were much better at enjoying food and other finer

things in life. They learned much form each other in the next two hundred

years.

These early settlers loved nicknames. The lightheartedness

of these French people was reflected in the nicknames they gave each other

and their towns. Kaskaskia was “pouilleux” - - (lousy_. Cape

Girardeau was “l’anse a’ la Graisse” - - (greasy cove). St. Lousi was

“Paincourt” - - (short of bread). The names they had for each other

were not derogatory, not used behind one’s back, but indications of warmth

and affection. Names like “Horse”, “Flakes”, “Possum”, “Bigfoot”, “Dizzy”,

“Funny”. The custom still persists today. Dad’s nickname was

“Buck” and it fit him well. He was short, about 5’8”, very strong and

stocky, not fat, but barrel-chested with broad shoulders, a thick 16 ½”

neck, and piercing blue eyes. He was quick to jump into a fracas an

stubbornly persistent in a cause.

The spelling of the last names has been changed over two

and a half centuries, Americanized to read phonetically in English close

to what they sounded like in French. In the Old Mines community some

of the most common names can be traced back to Quebec, New Orleans, and even

France. Names like Aubuchon, Becquette, DeGonia (originally DeGagner),

DeClue (De Clos), Merseal, Pashia (originally Page), Sancoucie and Politte.

But Boyer and Coleman are the most frequently found names. Dad’s cousins

were Polittes and Boyers and his mother was Marys Katherine Coleman of La

Vielle Mine (the old mine). A Catholic – of course! She spoke

only French and never learned more than a few phrases of English. As

recently as the early 1930’s, 90% of the parish member still used French

as the domestic tongue. The early Missouri French nonchalantly bestowed

their rugged pronunciations on other incoming nationalities and on places.

The Blue-Bellied Yank would have been an American with land so poor his belly

turned blue. Aux Arcs became Ozarks. This blending of cultures

in pronunciations and the isolation of the Missouri French led to the development

of a unique dialect probably difficult for the traditional French to understand.

Dad always referred to this dialect and he people as Paw Paw French, once

again there was the funloving insult – the reference to the Paw Paw Frenchman

who had to live on paw-paw in the summer and possums in the winter.

Dad’s father was William Washinton Vivrett, first born

of twelve children to Henry and Susan. Henry Jacen Vivrett was born

in Wilson Country near Nashville, Tennessee, in 1835. Henry was a farmer

and a good one but also an itinerant Baptist Circuit Preacher who help found

the Oakland Baptist Church on Big River. An amiable sort – who loved

to sing – one anecdote held he more than once closed a sermon by inviting

the entire congregation home for chicken dinner no advance notice to his

wife, Susan. Warm, cordial and friendly though he was, I’ve often wondered

what he thought of his oldest son marrying a Catholic girl.

I’ve traced old Henry back a bit. Two brothers came

from Alscon or Alason, a small village in France. This name runs throughout

the family for generations. The bachelor brothers came to American

before the Revolution and settled in Wilson County, Tennessee, near Nashville,

then Obion County, Tennessee on the Mississippi River.

In 1860, 74,000 American frontiersmen came into mid-Missouri.

For the most part, they were farmers and Missouri land was not only much

cheaper but similar to their beloved Tennessee uplands. Henry Jacen

Vivrett was one of them.

Another anecdote about Henry goes like this: As

a young farmer he was plowing a field near the Mississippi. It was

hot. He heard a steamboat whistle as it prepared to dock. He

tied off the mules’ reins and ran about two miles to the point where the

boat had docked. Henry reached into his overalls, showed the captain

his money and asked how far up river that amount would take him. “

St. Louis,” the Captain replied. And that’s one account of how Henry

married Susan Johnson on July 4,1860, less than a year before the Civil War

started.

Old Henry Jacen Vivrett left people in Western Kentucky

and Tennessee. One of them, Alascon Vivrett, had sons - - lots of them.

There were Jim, who fought for the Union, Dee and Bob. Also there were

Cage, Rufus, Tom, and his son Sack. (Sack may not have been quite right

but he was strong as an ox). Such names! I’ve heard Dad speak

of Cage and of Rufus, who had eight daughters and ruled his farm patriarchal

style.

My grandfather William was a stern patriarch too.

There was little praise and less affection to spread around. Still

Dad stayed home - - on the farm - - a bachelor who worked with mule teams

but courted with horses. He loved horses. In those days a young

man felt his horse must be fast, high spirited and have redundant four white

hocks. Few Missourians owned horseless carriages before 1910.

But the Missouri mule was of key importance on the farm.

When he was thirteen Dad went to the World’s Fair; an

experience he would never forget. Quite a culture shock for a farm

boy named Buck. St. Lous’ major claim to fame in 1904 was caskets,

shoes and beer. St. Louis was also the fourth largest city in the United

States. The glorious Fair - - with its innovations like iced tea, the

ice cream cone, the hotdog and Popsicles and its spectaculars like the “Pike”

and the ferris wheel with thirty six cars which could hold sixty people each.

Twenty million tourists visited this fair for an average of 100,000 per day.

What a grand time it must have been!

Buck had an agreement with his dad. If he stayed

with farming and worked their two farms, one owned and one leased, then someday

it would be his. So he farmed. But he was dreamer. The

St. Louis and Iron Mountain tracks went by the house and invariably brought

at least one adventurer who would hire on for awhile and then move on.

On Sundays, the young men would grow restless, catch a

freight with its engine laboring to climb a grade and ride as far south as

Poplar Bluff or sometimes into Arkansas; then catch another one home.

Dad marveled at the trains, their powerful engines belching smoke, the far-away

places the drifters talked about. And he always envied his cousin Sid

Boyer, just a little. Sid ran off an became a brakeman, then a conductor

for the Missouri Pacific. If a brakeman got hurt, he was immediately

unemployed. Not much security there, Dad reasoned, so he worked part

time as a brakeman once, but always there was the farm. In 1898 they

leased a river bottom farm from Lavina Blackwell of Blackwell, Missouri.

To a Missouri farmer, bottom land is the best. Dad loved that bottomland

farm and the river that ran through it. Big River then called it, and

still do. He told of working in the fields - - getting hot and racing

his brothers to the river, diving in clothes and all. But it could

be treacherous too and the hill folks had many stories of drownings and under-currents.

Still he loved that river as he did his horses and the trains. But

most of all he loved the land. He was a boy, working the land, when

Orville and Wilbur Wright made history. I asked him once what local

people thought about that flight and he responded, “Not much, on way or the

other”. Of course it was considerably after the fact by then.

Dad was working the land when the Yanks first went “over there” and when

they returned in triumph.

But all that changed! In June, 1922, his father, William

came to him and announced that he had traded the farm for an apartment building

on Wells Avenue, Wellston. By 1920 the close-in St. Louis suburb of

Wellston had grown by 22%. The Wellston property consisted of thirteen

apartments or flats, but Buck thought it was a bad deal, and he said so.

Dad was undone. He felt used and without a livelihood. After

thirty-one years of working towards a goal, suddenly there was no farm.

All but 40 acres was gone. Then he met my mother. They married

in May, 1924. dad was unemployed, had eight grades of education and

was thirty-four years old. The stage was set for forty years of doing

without.

From then on, times were always hard. In a letter,

dated November 3,1924, from St. Louis Dad writes his father that “a lot of

poor devils are out of a job but everyone says after the election things

will pick up.” But things did not pick up and babies began to arrive.

America had indeed lost its innocence and although Cal

Coolidge, elected in the above reference, seemed to represent solid virtues

of an earlier era, his leadership was inadequate in a post-war world.

Coolidge did not lead. He suggested and withdrew. The post war

prosperity was very fragile for the common man. Prosperity seemed more

attracted to some areas and some people than others. The “filter down”

theory of wealth never seemed to filter down, even then. Soon everything

collapsed.

In a letter dated June 20,1930, from Vineland my grandfather

pleaded with my Dad to “come down as I am in trouble. They came out

yesterday and took away my car.” Unable to help his son, old Henry,

the care-free farmer who had abandoned his team for adventure, was dead by

that November. My grandfather, William, died the next February.

How frustrating it must have been for my Dad to be unable to help either

of them when he was needed most. But his young growing family needed

him too.

Dad always liked Jews. Until his last days he repeated

the following incident as one reason. His bank had closed and $600

- - all their savings was unavailable and foreclosure on the flats was imminent.

In desperation, and uncharacteristically, he confided his frustrations to

a friend, Mr. Feischman, who immediately offered to help. Dad drove

him to the bank. He somehow was admitted and returned shortly out a

side door with the cash. With the banks closed and so many out of work, a

helpless public wanted reassurance and action. And got both!

Out parents were confirmed Democrats and one would have

thought F.D.R. invented the twin concepts of Hope and Happy Times or at least

he knew the road to travel to get there. Just mentioning Hoover’s name

would start Dad.

The Depression hit my folks late. With five children,

they got caught in the squeeze, couldn’t make the mortgage payment and lost

the apartment building that finally had been left them. In 1939, my

family, like Steinbeck’s Joad family in The Grapes of Wrath, became dispossessed

vagabonds, and uprooted victims of the relentless laws of supply and demand;

controlled by faceless, powerful forces in a nightmare world of bank runs,

foreclosures, day work only, and hang-me-downs, and hungry kids; always hungry

kids. There were “haves” and “have nots” and at that point, my family

knew which they were. Because I was the baby, I always had enough -

- though someone did without. I know who that was.

Steinbeck told us the land fell into fewer hands. But

he also realfirms the power of potential of unity; “two men are not as lonely

and perplexed as one” and Ma Joad says “… they ain’t gonna wipe us out. Why

we’re the people, we go on.” That’s the same way our mother held our family

together. A bond was there – stronger than economics and stronger that death.

“It’s blood.” Buck would say. “Yes Dear, “Mother wold respond, through she

knew the cement was Christian love – more than anything else.

As a family, 1939 was our hardest year. We struggled –

merely to survive. We were not alone! The typical family in 1940 was poor.

In 1940 half of all families in America earned less than $5,000. we were

poor – but clean. And Like the Missouri French two hundred years before us,

we were rich in the joy of each other. We settled in a small rural Missouri

town close to where Dad was born.

I don’t think Dad ever traveled east of St. Louis. He

finally got work as a sign hanger for Keller Sign Company of St. Louis and

was on the road a lot in Missouri. When World War 2 broke out, bother parents

worked seven days a week. After that, for a time we saw him only on weekends,

if at all. When the war ended, he went to work for himself as a house painter,

working eighteen hour days to make ends meet. Dad loved to paint. He felt

he was making something new again. He could paint equally well with either

hand and from first light till dusk, six days a week. I’ll never forget his

insisting that I sty on a fully extended ladder while he moved it from the

ground, and I can still hear Mother, budgeting, say “We have $700 saved.

If we can just make it through the winter…”

I can remember gathering times. As a family we’d go to

the woods for walnuts, hickory nuts, sassafras and persimmons. But most important

was to cut the Christmas tree. I can’t remember a “do without” Christmas,

though there must have been some – for our parents. Always there was security

and warmth of the cercle familial de joie (family circle of joy).

In 1954, Dad had a heart attack. He was sixty three years

old and he was tired. For awhile he just gave up. But he was a bull! After

a period of despondency he was back up again, seemingly stronger than before.

This was my senior year in high school. The others were all grown and gone.

My dad had an abundance of common sense, the kind of wisdom

not learned from books, but from life. For example, I was a long distance

runner but Dad refused to go to a meet. When I asked why, he said “ I can’t

see any sense in it. You’re just going around in circles.” He was right of

course.

In 1968, Dad had another heart attack. This one was massive

and nearly fatal. By this time I was through graduate school and teaching

at a junior college in Illinois. I realized how bad he was when he introduced

me to a nurse as the president of the college. I remember the wall by his

bed in the I. C. unit. Everything was white. Electronic devices and screens

were everywhere it seemed. I didn’t expect to see him again.

Dad loved our Mother and he loved his children. After

Mom’s death he would spend time each day reading the Bible and marking favorite

passages to reassure himself for what was to come. He believed in maintaining

respect for one’s name, the sanctity of marriage and the harbor of love in

a family. The last time we saw him, his two favorite hymns were sung at his

request: one a question – “Will The Circle Be Unbroken?” and the other a

comfort—“Amazing Grace.”

Just ten miles north LaVielle Mine on Highway 21, along

the turn off road to Big River, past rows of ancient cedars my Dad planted,

the land he worked and loved is still there. Along this road, on a corner

of the old homeplace farm, is the last home our parents shared, the cottage

where the two old men died. The large granite family marker he helped place

is still our there too. Like a lonely sentinel, the monolith stands on a

hill next to the road, a tribute for all seasons in reverence to the old

ones.

There is a mine on this, the family’s little farm too.

It too was an open pit mine, once quite active yields of lead and barite.

Periodically, the monolith, the memories and the mine

still call be back from my suburban mind – set to a simpler way and familiar

fields and woods I used to know. “Revenez encore a La Vielle Mine.” Come

back again to the Old Mine. And I do.

Dad

A bull named Buck

out

of hearty French stock

Crashing eighty successive seasons

against life’s corral gates

and never down long - -

but back again,

head lower than before

Asking no one for help

except, maybe, God

and Him not too often.

Is it a measure of manhood

to say you’re not hungry

when little children are?

Two daughters but three sons - -

One, uncompromising, obstinate - -

like him.

Another, silent, dependable - -

like him.

The youngest, determined, perseverant

- -

like him.

He hears only what he likes - -

in the Oriental fashion

Though he’s never been East

of the Illinois side.

What matter of man is this

who does without so long

and doesn’t become hollow?

who fights the battle of the cardiograph

in white hot intensity,

and gets up to walk out.

His understanding - - from wisdom;

his wisdom from life’s one-room, schoolhouse.

This master painter –

out of the hills

to create beauty

with housepaint,

and

dreams from sweat.

Ride the rails you, Blackwell boy!

Someday - -

Catch an engine

on a climb,

and ride those same rails

HOME.

EPILOGUE

On the last weekend in June 1971, we had a reunion of

the immediate family at my house to celebrate dad’s eightieth birthday.

The Missouri French loved family social gatherings and he enjoyed this one.

We didn’t have gambling or strong drink but there were activities inside

and out: great food, games, singing, much visiting between families

and home movies. I had edited and spliced together years of 8 mm film

and kept the film on continuous showings: pictures when mother was

alive, pictures of large family gatherings, and babies growing up.

Pictures of a warmer time. When it came time to unwrap birthday gifts,

the poem was given in a frame, brown ink on a parchment paper. I think

he liked it.

Mother had been gone for a year and a half and Dad’s last

years were lonely. He, too quickly, sold his little farm and just as

quickly felt homeless. “I do not have a home of my own anymore,” he

wrote in a dairy. And another place, “I should have kept my home till

death!”

I tried to visit him on weekends and he maintained his

dry wit and sense of humor. The early winter of ’79, he gave

up driving and I knew that was his way of preparing himself for the end.

This presented practical problems for him too, because his room was some

distance from favorite eating places - - and ice was coming.

On the weekend of December 9, I went to ask him to come

live with us. “I won’t be any trouble,” he quickly responded.

“You have my word on it.” For a moment I was silent, choked with emotion

- - and then very angry with myself. Why hadn’t I invited him to make

his home with me years ago? And I thought of Robert Frost’s great definition

of home: “Home is where - - when ya hav to go there - - they hav ta

take ya in” or “I should have called it something ya somehow haven’t ta deserve.”

Dad deserved better from me!

Those last months were pleasant - - together at Christmas

and afterwards gathered around a toasty fire every winter evening.

He loved to talk and eat and he’d laugh out loud at our son, wearing the

Siamese cat for a collar - - but a cough persisted: fluid building

in the lungs, our internist said.

Early on the morning of March 29, 1980, Dad died in the

bathroom but fully dressed - - just as his dad had, almost fifty years earlier.

He was gone before he hit the floor.

With his passing, a personal closeness with a slice of

Americana was gone from me. His life represented a span nearly one

half or our nation’s existence.

-- From the frontier roots of the Missouri French when Phillippe Francois

Renault was appointed director general of mining operations in New France

in 1719 and arrived in Kaskaskia in 1723.

-- the string of mining villages that followed, including Vielles (Old) mines

in 1726.

-- 1835 when Henry Jacen Vivertt was born near Nashville, Tennessee.

-- 1860 when seventy four thousand migrated to Missouri.

-- 1860 when Henry wed Susan Johnson less than a year before the Civil War

started.

--then more quickly - - the decades flash by - -

The Panic of 93’

The silver-tongued orator

Remember the Maine!

The Wright Brothers

The St, Louis World’s Fair

President McKinley assassinated

The Yanks are coming

Harding

Prohibition

Cal Coolidge

The ’26 Cardinals - - Me and Paul

Luck Lindy

The Babe

Brother can you spare a dime?

The War - - again - - WWII

The Nuclear Age

One small step - - in space

The Shuttle

The Global Village

They say history is the essence of innumerable biographies.

This was the story of one American’s Love affair with his land - - this glorious,

ongoing encounter with the land - - the gradually unfolding faith in the

land…what could be grown on it or what might be found under it.

Mid America had come of age and matured during his sojourn

in Missouri’s hills - - and like the steam engines he loved - - he belonged

to a bygone era - - a much simpler time when your word was your bond and

a handshake signed the contract.

…and how do you like this blueeyed boy, Dear Lord?

Written by Bill Vivrett

#3 Great Knight Court

Manchester, Missouri 63011

This page was created by Raymond Viverette. Any questions about its contents should be directed to the following e-mail address: viverette@yahoo.com