|

In May, 1951, when I began at The Houston Post, the newspaper was produced in a brick oven on the corner of Polk and Dowling. It was hellishly hot. Clattering fans, placed about the city room, created chaos. To try and control the fluttering sheets of copy paper, every desk had a spike -- a sharpened wire sticking up from a heavy square of lead. These were bloody, dangerous weapons, used for mock duels. The cry "Spike it!" meant that your story was too late or wasn't worth printing.

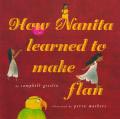

Later, in the new, air-conditioned city room across the street, I spent years facing Bill Bedell, assistant managing editor His smile was as permanent as a tattoo, but he didn't seem to know that he was smiling. Eventually I realized that the bigger his smile, the more upset he was. He edited a column called "Sound-Off," made up of letters from readers. Mr. Bedell suffered from constant complainers. Ted Welty, a dour old pro from the Brooklyn Eagle, was in charge of the copy desk. I think of him whenever there's a hurricane. He knew everything about such storms, and he stalked about with a little metal arrow from the Page 1 engraving of a map that showed the hurricane's path. He moved the arrow between each edition. For a few years, when Arthur Laro was feeling sadistic, he put me in charge of the Women's Department. I still treasure, however, the moment when club-and-garden-editor May Del Flagg, highly indignant on the telephone, said to some poor Houstonian, "Well! I've got a couple of things on MY chest that I want to get off!" Charlotte Phelan, Isabel Brown, David Westheimer and I had a regular luncheon club in a cleaning closet. We pushed aside the brooms, ate our sandwiches, and gossiped about books, movies, staff affairs and the Houston social scene. The closet filled with cigarette (and David's infernal cigar) smoke, dirty jokes and brilliant innuendo. The entertainment department was ruled over by a prickly Hubert Roussel. I liked to watch George Christian rush in from interviewing some movie star and begin sweating over his first sentence. He was unable to write until his lead was perfect. Deadline approached. The copy desk yelled for his copy. He sweated more. But when finally he got it right, the look of ecstasy on his face was a delight -- and so was his copy. Don Barthleme, sitting at George's elbow, never turned in a piece of copy that had a typo in it. If he hit a wrong key or wrote a phrase that turned out less than splendid, he tore the paper from his typewriter and started all over again. I had come to The Post from a small daily where one of my favorite jobs was setting headlines and grocery ads on a Ludlow. As a result, I liked to hang out in the back shop where I could hear the Linotypes' musical clink, clink, clink as the lines of lead dropped from their molds. The Post had a union shop so I wasn't allowed to touch anything, but I enjoyed the banter of the craftsmen who set the type and composed the pages in the big steel frames. If I could go back, I wouldn't mind that Pretini called me "Angel" because my ears are as big as wings. When I was trying to get a page closed on deadline, Pretini was the fastest and best. With computers and offset printing, that skillful crew and their magical machine became obsolete. Am I the only one left alive who is nostalgic for that time, that "foreign country" where things were done differently? In 1963, my typing fingers began to itch, and I started job jumping all over the U.S. I even spent a couple of years at the mighty New York Times where I often wished that, instead of a gang of sour, suspicious and superior damned Yankees, there was a Hubert Mewhinny sitting at the city desk, chipping away at a flint arrowhead. Biographical note: In addition to writing for the New York Times, Campbell Geeslin worked for Gannett newspapers, This Week magazine, Parade, Cue (a New York entertainment guide), People and Life. Then he edited a series of books about Nobel laureates and began writing children's books. Four have been published and a fifth is being illustrated. Two years ago the Cincinnati Opera commissioned him to write a libretto of one of his books, "How Nanita Learned to Make Flan." The opera is touring schools in the Midwest again this spring. A native of Brady, Texas, Geeslin and his wife live in White Plains, NY. They have three children and three grandchildren.Thanks to former Post book editor Liz Bennett for getting this contribution.