|

On September 9th, 1940, a Luftwaffe bomb fell on the north side of Buckingham Palace, lodging

itself under the stone steps outside the Regency Room. It did not explode and the King continued

to use his study which was immediately above it.

It went off, however, at 1:25 the next morning. No damage was done to the main structure, and there were no casualties as that part of the Palace had been evacuated for the night, but all the windows on all floors, including those of the Royal apartments, were shattered. Three days later the enemy struck again, and this time the escape was narrower. The following is an excerpt from the King's diary from that day. "..........We went to London and found an Air Raid in progress. The day was very cloudy & it was raining hard. We were both upstairs with Alec Hardinge (the King's Private Secretary) talking in my little sitting room overlooking the quadrangle; (I cannot use my ordinary one owing to the broken windows).....All of a sudden we heard an aircraft making a zooming noise above us, saw two bombs falling past the opposite side of the Palace, and then heard two resounding crashes as the bombs fell in the quadrangle about 30 yards away. We looked at each other, and then we were out into the passage as fast as we could get there....The whole thing happened in a matter of seconds. We all wondered why we weren't dead. Two great craters had appeared in the courtyard. The one nearest the Palace had burst a fire hydrant and water was pouring through the broken windows in the passage. 6 bombs had been dropped....." This experience created a new bond between the Monarchy and the British people.....The Queen remarking: "I'm glad we've been bombed....It makes me feel I can look the East End in the face."  of 14 year-old Princess Elizabeth's Radio message in October of 1940, broadcasted to British boys and girls who had been sent for safety abroad  ____

Princesses Elizabeth and Margaret Rose_____ ____

Princesses Elizabeth and Margaret Rose_____

If at this moment King George could not guarantee to his subjects a better future, he could at least formally recognize their gallantry in the present, but he was exercised in his mind as to what form this recognition should take. There existed many decorations and medals instituted by his predecessors for the reward of gallantry and meritorious conduct, but these, by their terms of reference, were restricted in the main to members of the armed forces and only one of them, the Victoria Cross, was open to award of all ranks. It was to meet this evident need that the King created the George Cross and Medal. It was the fruit of long deliberation and much careful study, both as to reference and design. The study of decorations was among King George's hobbies, and his collection of medals and ribbons at Windsor was among the most complete in the world. The planning of the George Cross and Medal was therefore of particular pleasure and interest to him, and the final design was almost entirely his own work, for he had sketched out an original device and had studied and amended with meticulous care the subsequent drafts presented to him. The decoration consists of a plain silver cross, with the Royal cipher "G.VI" in the angle of each limb. In the centre is a circular medallion showing St. George and the Dragon, and surrounded by an inscription, "For Gallantry". The reverse is plain and bears the name of the recipient and the date of the award. The cross, which is worn before all other decorations except the Victoria Cross, is suspended from a dark blue ribbon threaded through a bar adorned with laurel leaves. The King announced the creation of the George Cross in a broadcast to Britain and the Empire on September 23. He reminded them that they now stood in the front line, "to champion those liberties and traditions that are our heritage". "Winter lies before us, cold and dark....But after winter comes spring, and after our present trials will assuredly come victory and a release from these evil things. Let us then put our trust, as I do, in God, and in the unconquerable spirit of the British peoples".  of King-Emperor George VI BBC broadcast on the day Britain declared war on Nazi Germany (Windows Media Player)  ____

King George VI September 3, 1939 broadcast_____ ____

King George VI September 3, 1939 broadcast_____

of King-Emperor George VI BBC broadcast on VJ Day, the end of World War II (Windows Media Player)  ____

King George VI August 15, 1945 broadcast_____ ____

King George VI August 15, 1945 broadcast_____

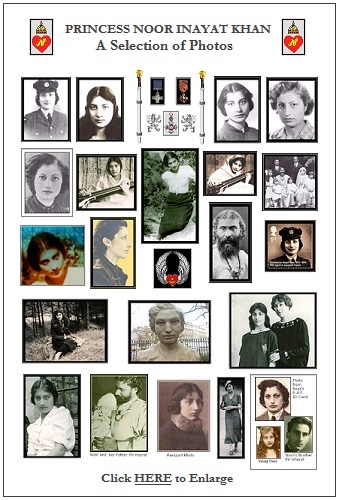

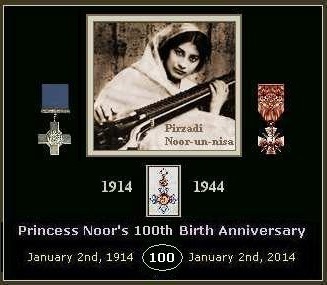

1939 Visit to Canada on the Video below:  Victoria Cross & George Cross Association Contact: Room 04, Archway Block South, Old Admiralty Building, Whitehall, London SW1, Tel 0171 930 3506  Noor Inayat Khan was born on 2 January 1914, in Moscow. She became an Assistant Section Officer in the Women's Auxiliary Air Force, seconded to the Women's Transport Service. Inayat Khan was the first women operator to be infiltrated into enemy occupied France, on 16 June 1943. During the weeks immediately following her arrival, the Gestapo made mass arrests in the Paris Resistance Groups to which she had been detailed, but although given the opportunity to return to England, she refused to abandon what had become the principal and most dangerous post in France. She was a wireless operator and did not wish to leave her French comrades without communications and she hoped also to rebuild her group. The Gestapo did their utmost to catch her and so break the last remaining link with London. After three and a half months she was betrayed, taken to Gestapo Headquarters in the Avenue Foch and asked to co-operate. She refused to give them information of any kind and was imprisoned in the Gestapo HQ, remaining there for several weeks, and making two unsuccessful attempts to escape during that time. She was asked to sign a declaration that she would make no further attempts but refused, so was sent to Germany for 'safe custody' (the first agent sent to Germany). She was imprisoned at Karlsruhe in November 1943 and later at Pforsheim, where her cell was apart from the main prison as she was considered a particularly dangerous and unco-operative prisoner. She still refused to give any information either as to her work or her comrades. On 12 September 1944 she was taken to Dachau Concentration Camp and shot on the following day. Noor Inayat Khan's George Cross was published in the London Gazette on 5 April 1949. She is commemorated on the Royal Air Force's Runnymede Memorial in Surrey, for those RAF personnel with no known grave. |