Uncle Eddie served in the Coast

Guard for twenty-one years including World War II I do not have the

specifics of Ed's service because of his missing service records. I do know that

he served on the Bouy Tenders Shrub W-244 and Lotus W-229 in the late

1930's and at Deer Island Light just prior to America's entry in WWII. Ed was

transferred from the East coast to Hawaii in 1942 but his asthma prevented him

from completing his assignment so he was reassigned to the U.S. Coast Guard

station in Ketchikan, Alaska for the remaining 20 months of the war, onboard the

USCGT Hemlock.

Uncle Eddie served in the Coast

Guard for twenty-one years including World War II I do not have the

specifics of Ed's service because of his missing service records. I do know that

he served on the Bouy Tenders Shrub W-244 and Lotus W-229 in the late

1930's and at Deer Island Light just prior to America's entry in WWII. Ed was

transferred from the East coast to Hawaii in 1942 but his asthma prevented him

from completing his assignment so he was reassigned to the U.S. Coast Guard

station in Ketchikan, Alaska for the remaining 20 months of the war, onboard the

USCGT Hemlock.

US LIGHT HOUSE SERVICE

Uncle Ed first entered the Light House Service in 1934. A civilian organization, he was assigned to his first duty station in Boston City harbor area.

The the US Lighthouse Service has it's origins dating back to August 7, 1789 when it was operated by the

Treasury Dept., In 1820, Steven Pleasanton, the 5th Auditor of the United States was in charge for the next 32 years. In 1852, a Lighthouse Board was established consisting of 2 officers of the Army Corp of Engineers, 2

civilian scientists, a junior officer from both Army and Navy to act as secretaries, was formed to oversee the service and did so for 58 years. In 1903, the service was transferred to Commerce Dept

and still under the Board control until 1910. Control of the Lighthouse Service was then transferred to the newly created department of Commerce and Labor in 1903. However, the Lighthouse Board still maintained control of the service until 1910, when it gave way to the Bureau of Light Houses under commissioner George Putnam.

The first

Treasury Dept., In 1820, Steven Pleasanton, the 5th Auditor of the United States was in charge for the next 32 years. In 1852, a Lighthouse Board was established consisting of 2 officers of the Army Corp of Engineers, 2

civilian scientists, a junior officer from both Army and Navy to act as secretaries, was formed to oversee the service and did so for 58 years. In 1903, the service was transferred to Commerce Dept

and still under the Board control until 1910. Control of the Lighthouse Service was then transferred to the newly created department of Commerce and Labor in 1903. However, the Lighthouse Board still maintained control of the service until 1910, when it gave way to the Bureau of Light Houses under commissioner George Putnam.

The first

Commissioner of Lighthouses was George Putnam. Putnam was the first and, very nearly, the last commissioner of the Lighthouse Service. His tenure extended from the service's inception until his retirement in 1935.

Putnam did more for the cause of navigational aids and their maintenance than

any other individual. He continued the Lighthouse Board's policy of experimentation and encouragement of new buoy designs. He also convinced Congress to allocate money for Lighthouse Service vessels,

and crusaded for his employees. Under Putnam the most important advances in long-range aids took place. The United States led the way with the new technology - the radio beacon. The advent

Commissioner of Lighthouses was George Putnam. Putnam was the first and, very nearly, the last commissioner of the Lighthouse Service. His tenure extended from the service's inception until his retirement in 1935.

Putnam did more for the cause of navigational aids and their maintenance than

any other individual. He continued the Lighthouse Board's policy of experimentation and encouragement of new buoy designs. He also convinced Congress to allocate money for Lighthouse Service vessels,

and crusaded for his employees. Under Putnam the most important advances in long-range aids took place. The United States led the way with the new technology - the radio beacon. The advent

of radio-beacon technology made buoys, lightships and lighthouses "visible" from significantly greater distances. No longer did a mariner have to physically see a buoy. The radio beacon made it possible for vessels equipped with a radio direction finder to take a bearing up to 70 miles from a navigational aid and, once identified, set a course relative to the aid.

Lighted buoys using compressed gas as a fuel gained popularity during Putnam's superintendence. Thirty years of trials and improvements, however, did not render the buoys entirely safe. The service issued instructions concerning safety in tending

Pintsch,

of radio-beacon technology made buoys, lightships and lighthouses "visible" from significantly greater distances. No longer did a mariner have to physically see a buoy. The radio beacon made it possible for vessels equipped with a radio direction finder to take a bearing up to 70 miles from a navigational aid and, once identified, set a course relative to the aid.

Lighted buoys using compressed gas as a fuel gained popularity during Putnam's superintendence. Thirty years of trials and improvements, however, did not render the buoys entirely safe. The service issued instructions concerning safety in tending

Pintsch,  Willson, and American Gas Accumulator buoys because of the explosive nature of compressed gas.

Most safety problems occurred during pressure tests. For example, in December 1910, an explosion of a Pintsch gas buoy killed a machinist attached to the tender Amaranth.

The machinist had completed a routine pressure test and had shut down the compressor.

According to Lighthouse Service reports, the buoy's cagework sheared away the mainmast of the Amaranth. The force of the explosion separated the top cone of the buoy from the body at the weld and hurled it through the roof of the depot's lamp shop. The blast forced the body of the buoy and its counterweight through the dock. The next issue of the Lighthouse Service Bulletin carried detailed instructions for pressure testing Pintsch gas buoys.

The Willson buoy, designed and

Willson, and American Gas Accumulator buoys because of the explosive nature of compressed gas.

Most safety problems occurred during pressure tests. For example, in December 1910, an explosion of a Pintsch gas buoy killed a machinist attached to the tender Amaranth.

The machinist had completed a routine pressure test and had shut down the compressor.

According to Lighthouse Service reports, the buoy's cagework sheared away the mainmast of the Amaranth. The force of the explosion separated the top cone of the buoy from the body at the weld and hurled it through the roof of the depot's lamp shop. The blast forced the body of the buoy and its counterweight through the dock. The next issue of the Lighthouse Service Bulletin carried detailed instructions for pressure testing Pintsch gas buoys.

The Willson buoy, designed and  patented by Canadian inventor Thomas

Willson, was inexplicably adopted by the Lighthouse Service. It also was a compressed- gas buoy, but worked on the carbide and water principle. Instead of pressurized gas, the fuel was solid calcium carbide, soaked with kerosene oil during the loading or "charging" process. This helped reduce the risk of explosion of the

calcium carbide. The Willson buoy was charged by drying the inside of the buoy completely and applying mineral oil to the sides of the fuel chamber. The calcium carbide slid through a

patented by Canadian inventor Thomas

Willson, was inexplicably adopted by the Lighthouse Service. It also was a compressed- gas buoy, but worked on the carbide and water principle. Instead of pressurized gas, the fuel was solid calcium carbide, soaked with kerosene oil during the loading or "charging" process. This helped reduce the risk of explosion of the

calcium carbide. The Willson buoy was charged by drying the inside of the buoy completely and applying mineral oil to the sides of the fuel chamber. The calcium carbide slid through a

canvas chute into the chamber. This was risky business. Even with the best precautions the risk of explosion still existed, as happened aboard the tender Hibiscus in 1913.

One explanation for this explosion was that a lump of carbide struck

the side of the chamber and created a spark. This accident occurred in a dead calm. Charging this type of buoy on a blustery day or in a fast-moving current must have been exciting, if not nearly impossible.

The end of World War I marked a turning point for the Lighthouse Service buoy tenders. During the war, men, vessels and equipment were transferred to the Navy. It quickly

canvas chute into the chamber. This was risky business. Even with the best precautions the risk of explosion still existed, as happened aboard the tender Hibiscus in 1913.

One explanation for this explosion was that a lump of carbide struck

the side of the chamber and created a spark. This accident occurred in a dead calm. Charging this type of buoy on a blustery day or in a fast-moving current must have been exciting, if not nearly impossible.

The end of World War I marked a turning point for the Lighthouse Service buoy tenders. During the war, men, vessels and equipment were transferred to the Navy. It quickly

discovered the tenders' usefulness in laying mines, as

well as for patrol duty off the Atlantic coast.

When the war ended, and the vessels were returned to the Lighthouse Service, the Navy proposed sending their old mine-layers to the service to work as tenders. This occurred at the same time Putnam was seeking money for new tender construction. The Navy, and several congressmen, believed that the Lighthouse Service could convert the old mine-layers into tenders. Congressional debates questioned the true nature of tenders, with some representatives openly asserting that these, of course, were merely pleasure boats for Lighthouse Service members. Putnam quickly suggested that the honorable congressmen

discovered the tenders' usefulness in laying mines, as

well as for patrol duty off the Atlantic coast.

When the war ended, and the vessels were returned to the Lighthouse Service, the Navy proposed sending their old mine-layers to the service to work as tenders. This occurred at the same time Putnam was seeking money for new tender construction. The Navy, and several congressmen, believed that the Lighthouse Service could convert the old mine-layers into tenders. Congressional debates questioned the true nature of tenders, with some representatives openly asserting that these, of course, were merely pleasure boats for Lighthouse Service members. Putnam quickly suggested that the honorable congressmen

come out for a

day aboard a buoy tender and see just how pleasurable it was.

In the end Putnam, Congress and the Navy reached a compromise: several ex-Navy mine-layers were converted for lighthouse supply service, and Putnam got what he was after in a more scaled-down form - a new building program to update his aging fleet - most still steam-powered, and some with stern- or side-paddle wheels. The new tenders were larger, diesel-powered, screw-propelled, and had a more advanced derrick and boom system. These tenders made the handling of compressed-gas buoys safer and more efficient.

Putnam retired in 1935.

Uncle Ed was assigned to the USLHST Lotus in mid to late 1930's The Lotus was

stationed in Boston and worked the navigational aids outside the harbor.

come out for a

day aboard a buoy tender and see just how pleasurable it was.

In the end Putnam, Congress and the Navy reached a compromise: several ex-Navy mine-layers were converted for lighthouse supply service, and Putnam got what he was after in a more scaled-down form - a new building program to update his aging fleet - most still steam-powered, and some with stern- or side-paddle wheels. The new tenders were larger, diesel-powered, screw-propelled, and had a more advanced derrick and boom system. These tenders made the handling of compressed-gas buoys safer and more efficient.

Putnam retired in 1935.

Uncle Ed was assigned to the USLHST Lotus in mid to late 1930's The Lotus was

stationed in Boston and worked the navigational aids outside the harbor.

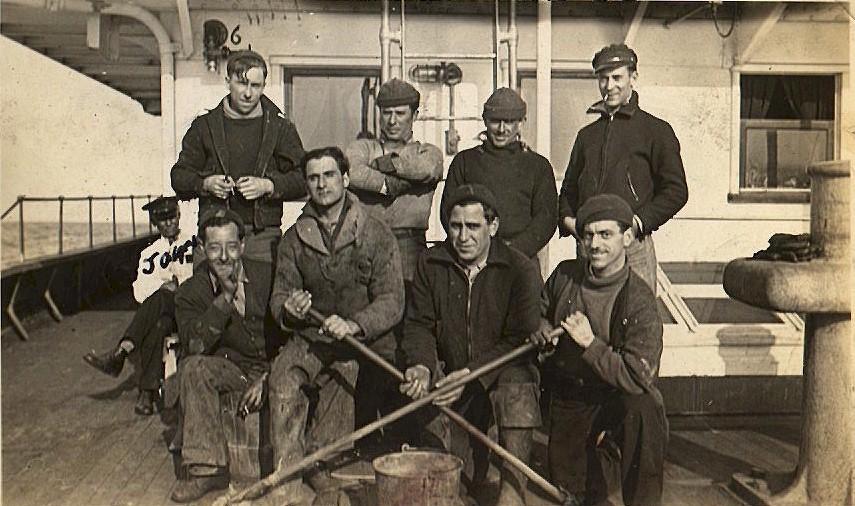

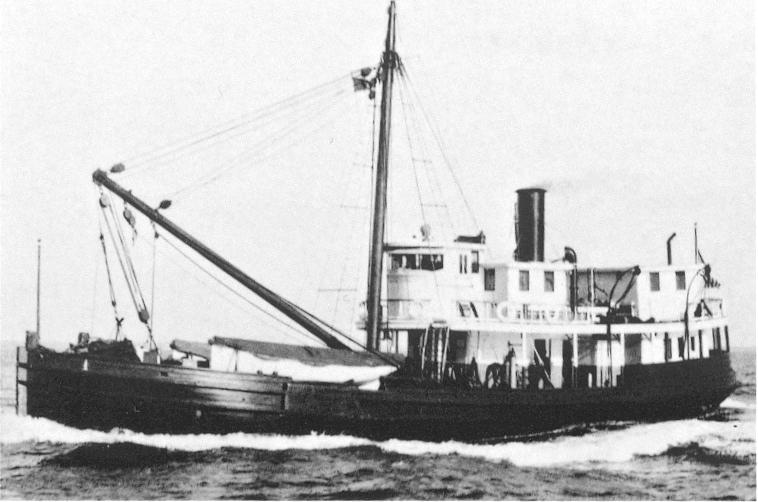

USCGT LOTUS WAGL-229

The LOTUS was built for the US Army Corps of Engineers as a mine planter. It was named the Col. Albert Todd, by the Fabricated Shipbuilding & Coddington Engineering of Milwaukee, WI in 1919. It was acquired by the USLHS in 1924, renovated and commissioned as USLHT LOTUS and replaced the USLHT Mayflower in the 2nd Lighthouse Division and homeported in Boston until the start of WWII when she was redesignated USCGC LOTUS WAGL 229 and served at Chelsea MA as a "AtoN" vessel and laying submarine nets in Newfoundland till 1943. She then was tranferred to the 10th Coast Guard District(CGD) at San Juan, Puerto Rico until 1944, when she was transferred to the 5th CGD at Norfolk VA till she was decommissioned 5 November 1946. She was sold 11 June 1947. (probably for scrap)

Cost of constyruction $540,000.00(1919)

Steel Hull

Length 172'6" x Beam 32' x Draft 17' x

Displacement 1130 tons

Main Engine - 2 Allis Chalmers compound, inverted, reciprocating steam

Main Boilers 2 Page Burton watertube (oil fired)

Twin Screw 1040 SHP

Complement 7 Officer - 24 Enlisted

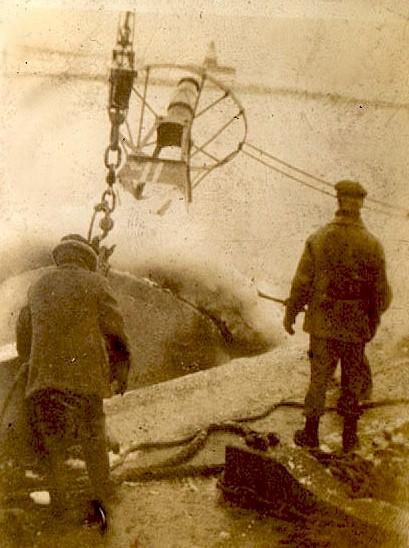

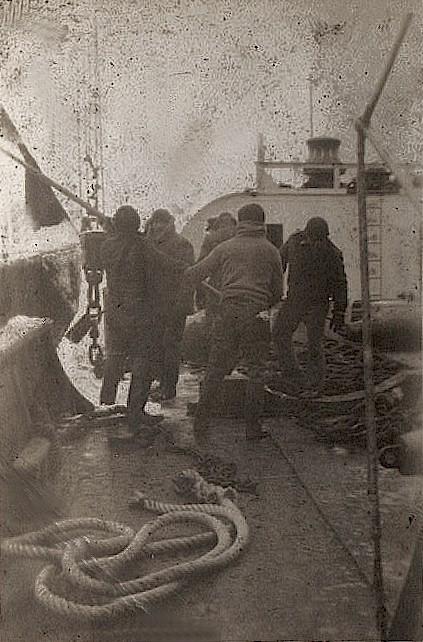

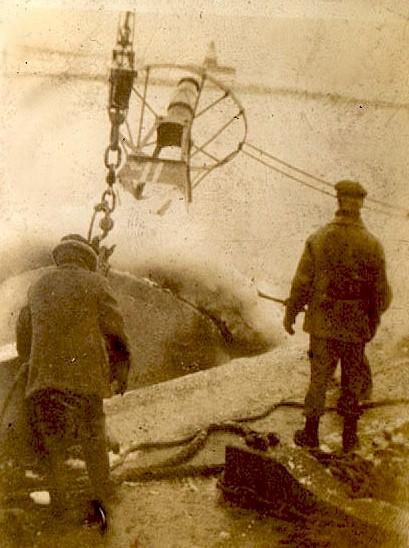

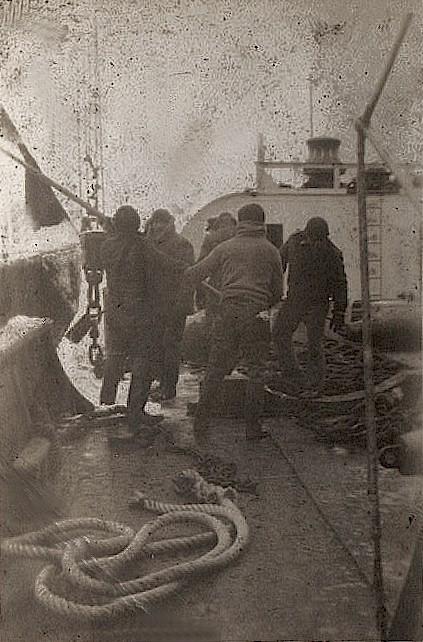

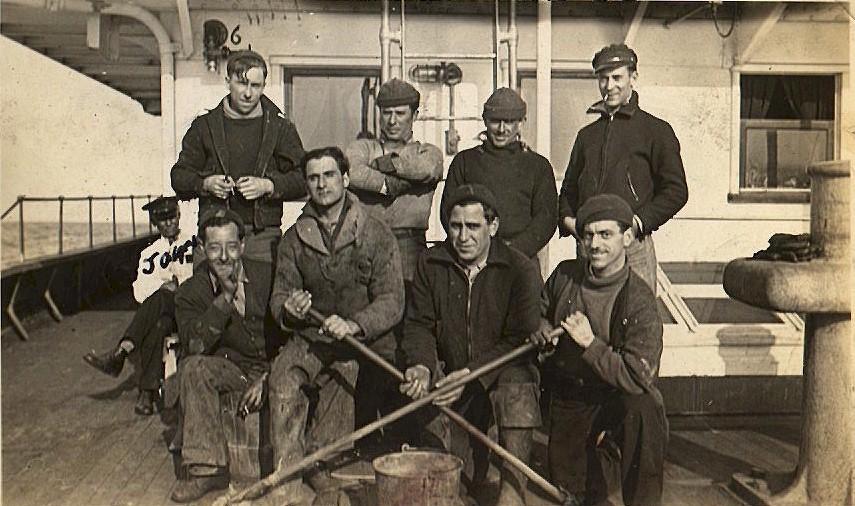

(Left) Tony Luiz on the superstructure of the Lotus (Center) USCGT Lotus crew eating in the mess (Right) Uncle Eddie(foreground) and his friend Tony Luiz repairing bouys on the forecastle of the Lotus

Gilbert Arruda

Uncle Gilbert served in the U.S. Lighthouse Service sometime during the mid to late thirties.

He also served with his brother Tony

Arruda in

the Massachusetts National Guard Although the specifics aren't well known, it is known that he served with them until they folded into the U.S. Coast Guard. The Lighthouse service was a civilian organization and Gilbert did not stay with them when they became part of the military. Gilbert continued to work on Bouys and navigational aids in the New Bedford, Massachusetts area, my mother Ruth Grenier spent a summer with him and remembers him going to the Woods Hole Oceangrapic Institute to work on the bouys fixing them. He also had several of them around his house.

My Aunt Patricia Arruda Andrews remembers the following from her days as a child that she spent with Uncle Gilbert: I remember that he use to paint the buoys down at the base. A couple of times he took me to work with him, but I stayed on the beach while he painted the buoys and I played in the water. He took me for a ride around the base where he use to work but all I remember was seeing a lot of old rusty buoys and heavy chains which he painted. I believe that was just a part-time job for him but I wouldn't swear to it. He stayed around the gas station(Gilbert owned a gas station) most of the time. His son Gilbert, Jr ran the repair part of the gas station, Theresa (daughter) and Uncle Gilbert ran the grocery, and ice-cream fountain part of the station and pumped the gas for the customers. I pumped the gas now and then and ate the ice cream and drank the milk shakes(frappes) that I also made. I really enjoyed myself each summer that I stayed there.

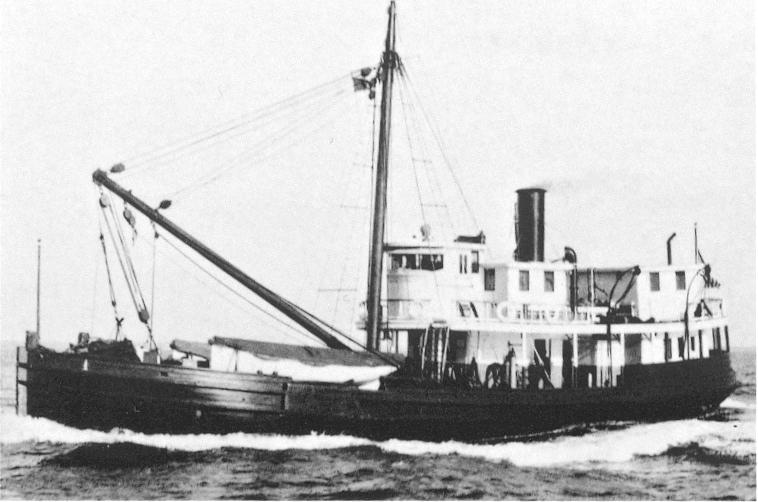

USCGT SHRUB WAGL-244

After Uncle Ed left the Lotus he went to a Light House Service depot station in

Boston for a short time he then transferred in the late 1930's early 1940 to

Bristol, Rhode Island. Uncle Ed served on the USCGT Shrub out of Bristol, it was during this time that the U.S. Lighthouse Service was folded into the Coast Guard in 1939. The Shrub was originally built as a private steam freighter (wood) in 1912 by William Abbott Shipbuilders, Milford, DE and

purchased by Mansfield & Son Company. The ship was aptly named the Mansfield & Sons. She was purchased by the US Navy in 1917 and served in the 2nd Naval District during WWI. After the war, she was acquired by the US Lighthouse Service. On 28 October 1919 she went into the yards and was rebuilt.

She was recommissioned in the Lighthouse Service on 31 July 1920 with the name SHRUB. She was assigned to the 2nd LH district (2LHD)in Boston, MA. While on normal duty tending bouys, she run aground on black rocks on Oct 6 1931 and sank in York Harbor, Maine. She was raised on 13 Oct 1931 and repaired at Staten Island NY at a cost of $39,156.00 and restored to full duty. At the start of WWII she was redesignated

USCGT Shrub WAGL-244 and continued to serve in New England out of Bristol RI.

She was decommissioned 1 July 1947 and sold in December of 1947 and became the Merchant

After Uncle Ed left the Lotus he went to a Light House Service depot station in

Boston for a short time he then transferred in the late 1930's early 1940 to

Bristol, Rhode Island. Uncle Ed served on the USCGT Shrub out of Bristol, it was during this time that the U.S. Lighthouse Service was folded into the Coast Guard in 1939. The Shrub was originally built as a private steam freighter (wood) in 1912 by William Abbott Shipbuilders, Milford, DE and

purchased by Mansfield & Son Company. The ship was aptly named the Mansfield & Sons. She was purchased by the US Navy in 1917 and served in the 2nd Naval District during WWI. After the war, she was acquired by the US Lighthouse Service. On 28 October 1919 she went into the yards and was rebuilt.

She was recommissioned in the Lighthouse Service on 31 July 1920 with the name SHRUB. She was assigned to the 2nd LH district (2LHD)in Boston, MA. While on normal duty tending bouys, she run aground on black rocks on Oct 6 1931 and sank in York Harbor, Maine. She was raised on 13 Oct 1931 and repaired at Staten Island NY at a cost of $39,156.00 and restored to full duty. At the start of WWII she was redesignated

USCGT Shrub WAGL-244 and continued to serve in New England out of Bristol RI.

She was decommissioned 1 July 1947 and sold in December of 1947 and became the Merchant

vessel Shrub, operating till 1966 when she was scrapped.

vessel Shrub, operating till 1966 when she was scrapped.

Original purchace price $42,000.00(1917)

Length 107' x Beam 29' x Draft 6'6" (light) x

Displacement 435 tons max

Main engine 1 compound reciprocating

Main boiler 1 watertube 150 psi (coal fired)

Single screw 278 SHP

Complement 2 officers and 13 enlisteds

US Coast Guard Service

In

July of 1939 the US Light house service was incorporated into the US Coast Guard. For Uncle Ed this meant a simple paperwork shuffle as his duties and responsibilities remained the same. After the Shrub Uncle Ed would transfer to several places throughout his career.

Congress moved the Lighthouse Service out of the Department of Commerce and incorporated it into the Coast Guard. On May 9, 1939, President Franklin D. Roosevelt announced his reorganization plan II, under which the Lighthouse Service under the Department of Commerce would be transferred to the Treasury Department, and eventually to the U.S. Coast Guard. The transfer became effective on

July 1, 1939.

In one stroke of a pen, the Coast Guard expanded its ranks from 10,164 to 14,283 personnel, but there were complications. All of the 4,119 Lighthouse personnel were civilian employees not military. The process of incorporating these civilians into the Coast Guard would not be an easy task.

Transfer of the Staff and equipment of the Bureau of Light Houses to Coast Guard headquarters was completed in less than a week. Coast Guard Commandant Admiral Waesche appointed boards composed of three officers in each district to decide which lighthouse service employees would be permitted into induction into the coast guard, and also

recommend ranks and rates for them. Light Keepers general became Chief or First Class Petty Officers, Junior Officers in tenders were offered warrant officer appointments and most tender masters and chief engineers were commissioned chief boatswains and chief machinist mate warrant officers.

In

July of 1939 the US Light house service was incorporated into the US Coast Guard. For Uncle Ed this meant a simple paperwork shuffle as his duties and responsibilities remained the same. After the Shrub Uncle Ed would transfer to several places throughout his career.

Congress moved the Lighthouse Service out of the Department of Commerce and incorporated it into the Coast Guard. On May 9, 1939, President Franklin D. Roosevelt announced his reorganization plan II, under which the Lighthouse Service under the Department of Commerce would be transferred to the Treasury Department, and eventually to the U.S. Coast Guard. The transfer became effective on

July 1, 1939.

In one stroke of a pen, the Coast Guard expanded its ranks from 10,164 to 14,283 personnel, but there were complications. All of the 4,119 Lighthouse personnel were civilian employees not military. The process of incorporating these civilians into the Coast Guard would not be an easy task.

Transfer of the Staff and equipment of the Bureau of Light Houses to Coast Guard headquarters was completed in less than a week. Coast Guard Commandant Admiral Waesche appointed boards composed of three officers in each district to decide which lighthouse service employees would be permitted into induction into the coast guard, and also

recommend ranks and rates for them. Light Keepers general became Chief or First Class Petty Officers, Junior Officers in tenders were offered warrant officer appointments and most tender masters and chief engineers were commissioned chief boatswains and chief machinist mate warrant officers.

Deer Island Light, MA

After Uncle Ed transferred from the Shrub he was assigned to the lighthouse at

deer Island outside of Boston harbor. Deer Island Light is located south of the town of Winthrop, Massachusetts, about 500 yards from Deer Island. Deer Island itself has a sordid past as an internment camp for Indians during King Philip's War, the site of a state prison, and a quarantine station where many immigrants died. Today the island is home to a mammoth sewage treatment plant for the Boston area. Deer Island actually ceased being an island in the 1930s, when Shirley Gut, which separated it from Winthrop, was filled in.

Uncle Eddie was stationed at Deer Island Light for a short period of time then he transferred to Hawaii at the start of WWII. Click here for more on the Deer Island Lighthouse

After Uncle Ed transferred from the Shrub he was assigned to the lighthouse at

deer Island outside of Boston harbor. Deer Island Light is located south of the town of Winthrop, Massachusetts, about 500 yards from Deer Island. Deer Island itself has a sordid past as an internment camp for Indians during King Philip's War, the site of a state prison, and a quarantine station where many immigrants died. Today the island is home to a mammoth sewage treatment plant for the Boston area. Deer Island actually ceased being an island in the 1930s, when Shirley Gut, which separated it from Winthrop, was filled in.

Uncle Eddie was stationed at Deer Island Light for a short period of time then he transferred to Hawaii at the start of WWII. Click here for more on the Deer Island Lighthouse

Treasury Dept., In 1820, Steven Pleasanton, the 5th Auditor of the United States was in charge for the next 32 years. In 1852, a Lighthouse Board was established consisting of 2 officers of the Army Corp of Engineers, 2

civilian scientists, a junior officer from both Army and Navy to act as secretaries, was formed to oversee the service and did so for 58 years. In 1903, the service was transferred to Commerce Dept

and still under the Board control until 1910. Control of the Lighthouse Service was then transferred to the newly created department of Commerce and Labor in 1903. However, the Lighthouse Board still maintained control of the service until 1910, when it gave way to the Bureau of Light Houses under commissioner George Putnam.

The first

Treasury Dept., In 1820, Steven Pleasanton, the 5th Auditor of the United States was in charge for the next 32 years. In 1852, a Lighthouse Board was established consisting of 2 officers of the Army Corp of Engineers, 2

civilian scientists, a junior officer from both Army and Navy to act as secretaries, was formed to oversee the service and did so for 58 years. In 1903, the service was transferred to Commerce Dept

and still under the Board control until 1910. Control of the Lighthouse Service was then transferred to the newly created department of Commerce and Labor in 1903. However, the Lighthouse Board still maintained control of the service until 1910, when it gave way to the Bureau of Light Houses under commissioner George Putnam.

The first

discovered the tenders' usefulness in laying mines, as

well as for patrol duty off the Atlantic coast.

When the war ended, and the vessels were returned to the Lighthouse Service, the Navy proposed sending their old mine-layers to the service to work as tenders. This occurred at the same time Putnam was seeking money for new tender construction. The Navy, and several congressmen, believed that the Lighthouse Service could convert the old mine-layers into tenders. Congressional debates questioned the true nature of tenders, with some representatives openly asserting that these, of course, were merely pleasure boats for Lighthouse Service members. Putnam quickly suggested that the honorable congressmen

discovered the tenders' usefulness in laying mines, as

well as for patrol duty off the Atlantic coast.

When the war ended, and the vessels were returned to the Lighthouse Service, the Navy proposed sending their old mine-layers to the service to work as tenders. This occurred at the same time Putnam was seeking money for new tender construction. The Navy, and several congressmen, believed that the Lighthouse Service could convert the old mine-layers into tenders. Congressional debates questioned the true nature of tenders, with some representatives openly asserting that these, of course, were merely pleasure boats for Lighthouse Service members. Putnam quickly suggested that the honorable congressmen

After Uncle Ed transferred from the Shrub he was assigned to the lighthouse at

deer Island outside of Boston harbor. Deer Island Light is located south of the town of Winthrop, Massachusetts, about 500 yards from Deer Island. Deer Island itself has a sordid past as an internment camp for Indians during King Philip's War, the site of a state prison, and a quarantine station where many immigrants died. Today the island is home to a mammoth sewage treatment plant for the Boston area. Deer Island actually ceased being an island in the 1930s, when Shirley Gut, which separated it from Winthrop, was filled in.

Uncle Eddie was stationed at Deer Island Light for a short period of time then he transferred to Hawaii at the start of WWII. Click here for more on the Deer Island Lighthouse

After Uncle Ed transferred from the Shrub he was assigned to the lighthouse at

deer Island outside of Boston harbor. Deer Island Light is located south of the town of Winthrop, Massachusetts, about 500 yards from Deer Island. Deer Island itself has a sordid past as an internment camp for Indians during King Philip's War, the site of a state prison, and a quarantine station where many immigrants died. Today the island is home to a mammoth sewage treatment plant for the Boston area. Deer Island actually ceased being an island in the 1930s, when Shirley Gut, which separated it from Winthrop, was filled in.

Uncle Eddie was stationed at Deer Island Light for a short period of time then he transferred to Hawaii at the start of WWII. Click here for more on the Deer Island Lighthouse

WWII

- U.S. Coast Guard - Ketchikan, Alaska

WWII

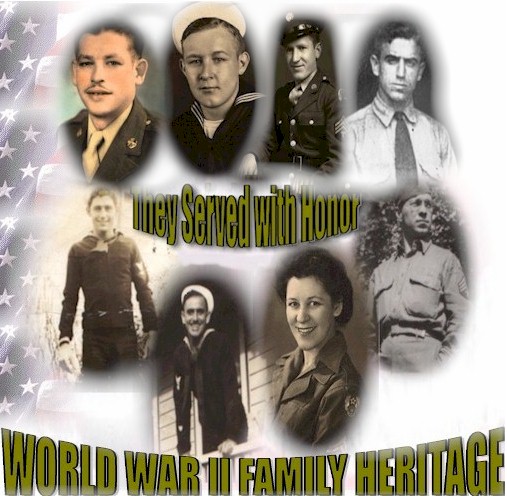

- U.S. Coast Guard - Ketchikan, Alaska They

Served with Honor : Home Page

They

Served with Honor : Home Page