A major obstacle to the economic and social development of Laos has been its poor transportation system. Rivers like the Mekong and few roads are the major avenues of communication, supplemented by air transport.

Well established as an exceptionally

rewarding travel destination, Thailand today offers a new dimension to its myriad attractions as a gateway to the Mekong region, opening up what is effectively Southeast Asia's last tourism frontier. Countries once difficult to visit are now becoming increasingly accessible, making it possible to experience an extraordinary wealth of historic, cultural and scenic sights.

Southern China's Yunnan province, Myanmar, Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam, as well as north and North eastern Thailand all share to a greater or lesser extent the passage of the mighty Mekong, Southeast Asia's longest river at 4,200 kilometres.

Each of these six Mekong countries has its own unique attractions. Ancient monuments and old royal capitals bear witness to an illustrious past, while lifestyles present fascinating and contrasting images. Natural sights also abound, from the mountain gorges of northwest China to primeval rainforests, from wooded valleys to vast flood plains. And because the Mekong has been little explored or exploited, all remains as pristine as you'll find anywhere in the world today.

With direct air links from Bangkok, most major Mekong destinations can be quickly and comfortably reached, although there is nothing to beat a slow boat on the

river itself. Of the many options open to the traveller, Laos is especially rewarding; it

is the closest to Thailand and yet it remains arguably the least changed, most traditional

of all the Mekong countries.

More than anywhere else, Laos seems to belong quintessentially to the river. A sinuous thread running through the nation's historical and cultural fabric, the Mekong has helped shape the country's past and continues to be the focus of settlement.

The Land of a Million Elephants, as Laos was originally known, grew up on the banks of the Mekong which flows through or borders the nation's entire western flank. Luang Prabang, the old royal city founded in the 14th century overlooks the river. So,

too, does the modern capital, Vientiane.

With more than two thirds of Lao territory taken up by mountain ranges, highlands and plateau, the Mekong is the economic lifeline. Its flood plains provide the

major wet-rice lands; its waters yield fish, the main source of protein; its passage of more than 1,000 kilometres affords the most convenient north-south communication link.

Like the country itself, for long shutting itself off from the outside world, the Mekong in Laos retains an air of mystery and romance. No dam slows its passage, and only since April 1994, has a bridge spanned its banks. Travelling the river remains, as I

discovered, a journey of exploration, of an enchantment that is timeless.

My starting point was the "Golden Triangle", where the Mekong and the tiny Ruak tributary momentarily bring together the borders of Thailand, Myanmar and Laos.Set amid the forested hills of Thailand's far north it is a scenic and evocative spot, though not without its modern comforts in the form of deluxe accommodation at the Golden Triangle Resort or Le Meridien Baan Boran. But if that's not your idea of adventure then you only have to look across the river to Laos where the river banks remain virgin in their vegetation cover and it could be the 19th century still.

There is no crossing point here so the first stage of our journey took us 80 kilometres downstream to Chiang Khong. Several hundred metres wide at this point, the Mekong is untamed, swift-flowing and stained a deep red-brown. Our transport was a typical

Thai longtail boat, looking as sleek and as slippery as a varnished banana skin. The propeller, at the end of a long shaft, was powered by a 1,300 cc Toyota car engine and the boatman, perched on a box next to this excess of power, proudly shouted above the din that

he could get up to 100 kph.

We shot off like a torpedo. The Golden Triangle quickly vanished and the near pristine world of the Mekong enveloped us. To our left was the silent, almost secretive land of Laos; on the right the Thai side seemed only slightly more developed, with the

glimpse of a road winding among the hills above the river. Soon the valley narrowed and the river cut a course between steep wooded hills, sometimes receding, more often sweeping down to the high banks. Even in the dry season, before the Mekong becomes swollen by the monsoon rains, the current is strong and the flow turbulent in places due to rocky shoals making it a river which commands respect.

It is also a stunningly beautiful river. There is little traffic and few villages along the banks in this stretch, and the sheer grandeur of the scenery is

breathtaking. The broad sweep of the river itself, framed by the majestic heights of the densely forested hills offers a landscape that appears totally remote from the modern world.

Our exhilarating dash along this emotive river road took a pause after about an hour, when we pulled into one of the few villages on the Thai side. It was a typical riverine settlement comprising some 50 old wooden houses built on stilts, with the population supporting itself by cultivating the surrounding fields. A supplementary source of income comes, owever, from weaving and in the open spaces beneath the houses women were at work on primitive hand looms, turning out gorgeously patterned cloth of a quality

seemingly at odds with such a basic means of production.

Back on the river its was another 45 minutes high-speed boat ride down to the little market town of Chiang Khong, perched high above the river, across the water from its Lao counterpart, the even smaller, sleepier town of Ban Houei Sai. I left the boat at Chiang Khong and explored what proved to be a delightfully laid-back place, its streets given a exotic touch by the sight of Hmong and other tribespeople attracted to the hardware stores and fresh produce market. Compensating for a lack of major sights was the friendly, easy-going atmosphere of a country town content to be simply itself.

Chiang Khong does have one claim to fame, however, as a centre of fishing for the famous pla beuk. Unique to the Mekong, these giant catfish,

scientifically named Pangasianodon gigas, can weigh up to 250-300 kilos, making it possibly the heaviest freshwater fish in the world. Little is known about its life cycle and migration patterns, and over the years myths and legends have grown up around the mysterious pla beuk, some folk tales claiming the fish inhabits underwater caves of gold. Though no one any longer really believes the more far-fetched stories, the fishing of this gentle giant continues to entail elaborate rituals and superstitious practices.

The pla beuk's meat is expensive, highly prized not only for its robust flavour but also for its purported power to enhance sexual powers. Accordingly, it has been heavily fished and this, along with changes in the nature of the riverbed, has

brought about a drastic decline in numbers. Once widely found in the Lower Mekong, pla beuk are today caught almost exclusively in the vicinity of Chiang Khong, where an average of 40 to 60 fish are netted annually during the April-May season.

Concern for the survival of the species has prompted Thailand's Fisheries Department to experiment with induced breeding. As one official put it,The pla beuk is the symbol and treasure of the Mekong River.

If we don't preserve it now, I believe the fish will soon be extinct. Attempts at artificial fertilization and breeding have met with some success, but the future of the giant catfish is far from

assured.

If we don't preserve it now, I believe the fish will soon be extinct. Attempts at artificial fertilization and breeding have met with some success, but the future of the giant catfish is far from

assured.

From Chiang Khong it is a short ferry ride across the Mekong into Laos and the energetic little riverport of Ban Houei Sai. Living mostly on timber exports, it turns out to be busier than it looked, with a crowd of traditionally costumed highlanders adding a dash of colour to the crowd thronging the landing stage where a dozen boats are drawn up.

Here I began a five-day run down the Mekong to Vientiane via Luang Prabang, a journey of 757 kilometres. Our transport was a typical Lao wooden river boat, 22-metres long, two metres wide, with a wheel house at the bows, tiny toilet and cooking area at the stern and in between, beneath a flat roof, an empty hull clearly designed more for the convenience

of cargo than passengers.

Discomforts were, however, forgotten once we were underway. Although fairly narrow in these parts, the Mekong is exciting, flowing through wild, beautiful hill country.

After skirting the Thai border for a while, I headed east into Laos. The scenery became if anything even more spectacular and we met little on the river or its banks to detract from a feeling of isolation in a lost world. The sensation was not banished by the night's stop at Pak Beng. This, the largest river settlement between Ban Houei Sai and Luang Prabang, is a collection of some 500 wooden houses nestling in the

folds of the steep hills which trap the river in a narrow passage. It is an eerily isolated spot, given substance only by the river.

Throughout the next day the river maintained a stunning passage through a narrow valley. Forested mountains loomed on both sides, their slopes here and there ablaze as villagers burnt off the scrub to prepare the land for cultivation. Wisps of smoked curled over the surface of the water while ash like flakes of black snow played in the air.

Traffic was few and far between and only ocasionally did we pass other boats. Most were the same design as ours, all were laden with people, goods and even water buffalo. Now and then we spotted fishermen casting their nets from rocks, their solitude

striking as villages were rarely seen.

By afternoon we reached the mouth of the Nam Ou tributary where the Mekong curves to head south. The point is marked on the right bank by a sheer cliff into which is set Tham Ting, a 400-year-old cave temple. Stacked with hundreds of Buddha images, this is

an especially sacred spot, once the venue for an annual celebration presided over by the King of Laos.

I moored at the foot of a short steep flight of steps and our boat,s crew hopped ashore to pay their respects. Lighting incense and offering up prayers, they filled the cave with a religious atmosphere that was awesome in such a remote spot.

On the final stretch down to Luang Prabang the river widens and there were more boats, more people. And gold. Camping out on the sandbanks were scores of families who for half the year are farmers but turn gold prospectors during the dry season. Typically it

was the women who were doing the most work, digging pay dirt out of shallow pits and washing it in wooden trays at the river's edge. If they're lucky they find tiny flecks of gold glinting amid the blackish sand. "I can usually find as much as a gramme of gold

a day,said one prospector. It seemed a lot to me, though judging by the numbers of panners, these unlikely goldfields must be productive.

After cave temples and gold seekers, Luang Prabang was a fitting terminus to an enchanted day. Shaded by trees and with an imposing site on the banks of the Mekong where it is joined by the Nam Khan river, this ancient royal city appeared to have changed

little since travel writer Norman Lewis described it in 1950.

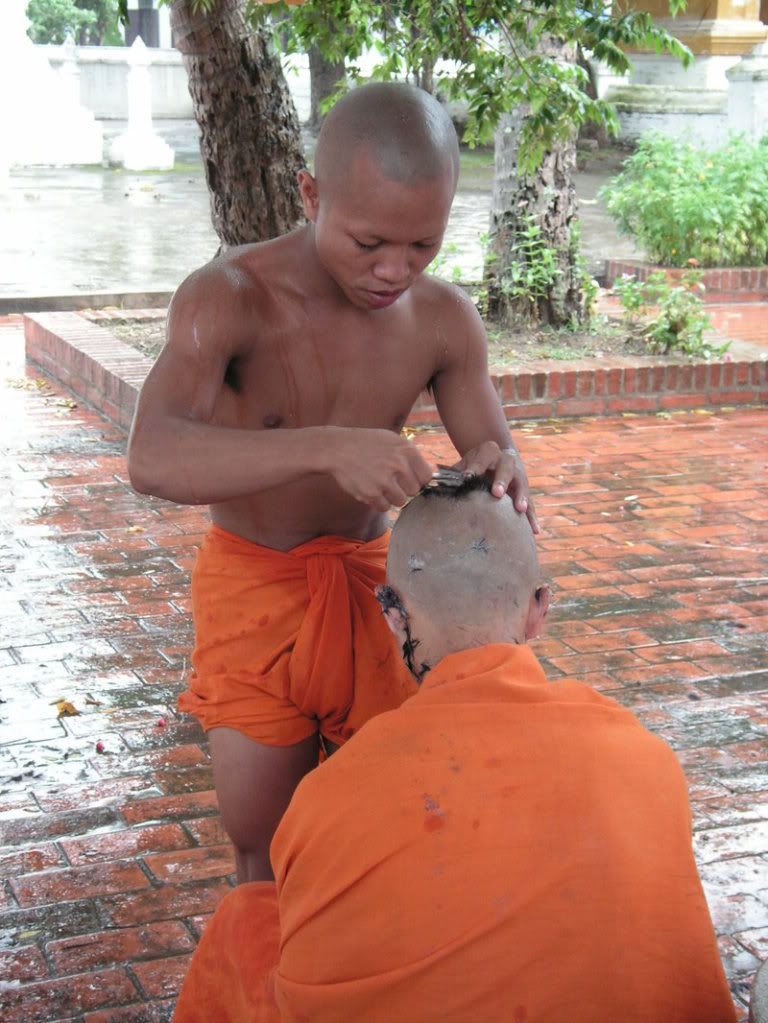

Luang Prabang, on its tongue of land where the rivers meet, was a tiny Amsterdam, but an Amsterdam with holy men in yellow robes in its avenues.... Down at the lower tip, where Wall Street should have been, was a great congestion of monasteries."

Luang Prabang, on its tongue of land where the rivers meet, was a tiny Amsterdam, but an Amsterdam with holy men in yellow robes in its avenues.... Down at the lower tip, where Wall Street should have been, was a great congestion of monasteries."

Indeed, Luang Prabang has an immediate and seductive charm. Surrounded by mist-shrouded mountains which have stood as mute sentinels, it endures as an outpost of old Asia.

Its "congestion of monasteries" survives, and the resplendent former royal shrine of Wat Xiengthong, built in 1560, and the late 18th-century Wat May with its low sweeping, multi-tiered roofs, along with a handful of other venerable Buddhist

temples, all attest to centuries of devotion, while the masterly lines and proportions of the architecture are complemented by decorative detail that's the very stuff of Oriental fairy-tales.

The day's sightseeing I allowed myselves was scarcely sufficient to absorb it all, but the river beckoned. Leaving Luang Prabang in the early morning I was immediately plunged into a scene from Conrad. Mist rising like steam from the still water enveloped me, reducing visibility to but a few feet. Twice we had to stop. With the engines cut, the heavy silence conspired with the mist to wall us in. For half an hour we waited until the weather cleared and slowly the river took form.

The most remarkable feature of the Mekong in this stretch is its vastly varying widths. From placid passages several hundred metres across, it will suddenly change mood and angrily tumble through rocky narrows. Yet it is an enchanting passage. Of the river

here, explorer Henri Mouhot wrote in 1860: "In this part of the country...it everywhere runs between lofty mountains, down whose sides flow torrents, all bringing their tribute. There is almost an excess of grandeur. The eye rests constantly on these mountains slopes, clothed in the richest and thickest verdure.

For two days, with an overnight stop in the fairly prosperous river port of Pak Lay, our view was the same as Mouhot's. Only after the river had swung east for its run to Vientiane did the scene change as the hills gradually receded and the valley broadened,

the river expanding into a broad sweep as it flows by the Laotian capital.

After Luang Prabang, Vientiane seemed an eccentric kind of place, a provincial town posing as a capital city. Small and tranquil, the city presents a marked contrast to the frenetic air of more typically crowded Asian capitals.

After Luang Prabang, Vientiane seemed an eccentric kind of place, a provincial town posing as a capital city. Small and tranquil, the city presents a marked contrast to the frenetic air of more typically crowded Asian capitals.

Located on the left bank of the Mekong, opposite Thailand's Nong Khai province, Vientiane's charm lies in its still largely preserved traditional character defined by an oddly attractive blend of Asian and French colonial architecture.

Sightseeing includes the principle temples of Wat Phra Keo, which once enshrined the Emerald Buddha now in Bangkok, and Wat Sisaket, although Iwas most impressed by That Luang. This is the nation's most sacred shrine, originally constructed in 1556, and is fascinating for its display of pure Laotian architecture seen in the distinctive square stupa of sober yet graceful lines that give it a remarkable beauty despite it lack of obvious ornamentation.

Beyond Vientiane, in the southern part of the country, is the final Lao stretch of the Mekong and one of its wonders, the Khone Falls. This, the largest waterfall on the entire river, is magnificent and the sight of the most formidable barrier to navigation on the river rewards hours of travel.

The name Khone is used loosely and there are actually two principal cascades, Phapheng Falls and Somphamit Falls. These are but the two most dramatic features in a 13-kilometre stretch of rapids that form perhaps the single most wondrous passage of the

Mekong.

Just before the river enters Cambodia it divides into several channels at the huge island of Khong. The distance between the westernmost and easternmost streams is 14 kilometres, the greatest width assumed by the river throughout its 4,200-km course.

Downstream of Khong numerous other smaller islands, of which Khone is one, create a maze of channels, some placid creeks, others raging torrents where the river plunges over rocks in a mad rush to get beyond these obstacles and continue a more leisurely journey.

Just before the river enters Cambodia it divides into several channels at the huge island of Khong. The distance between the westernmost and easternmost streams is 14 kilometres, the greatest width assumed by the river throughout its 4,200-km course.

Downstream of Khong numerous other smaller islands, of which Khone is one, create a maze of channels, some placid creeks, others raging torrents where the river plunges over rocks in a mad rush to get beyond these obstacles and continue a more leisurely journey.

With no time to travel the Mekong's long middle reach in Laos, I flew from Vientiane to Pakse, gateway to Khone. This provincial capital, located on the left bank of the river at the junction of the Se Done tributary, is a major Mekong town, a crossroads

for both road and river traffic.

Backed by a steep escarpment, the town is dominated by the former palace of Prince Boun Oum of Champassak, a delirious building of Oriental wedding cake architecture. Viewed close up, however, it was all too apparent that Pakse has seen better days. A handful of dilapidated colonial-period buildings lend an air of old-world charm, but the sights, as I discovered, are quickly exhausted.

No boat was immediately available for my trip to Khone so rather than wait, I decided to go by road, taking a four-wheel-drive to cover the 136 kilometres to Khinak, the last riverine settlement of any note before the twilight zone of the Cambodia border.

No more than a string of wooden houses clinging to the east bank of the Mekong, Khinak is much smaller and much more charming than Pakse; the kind of place that makes you understand why the French colonials thought Laos an earthly paradise. At sunset children

came to play in the river and sarong-clad women bathed with delicacy and grace.

Below Khinak the Mekong ceases to be its usual placid self. Disgruntled at having to find diverse paths between a hundred or so islands, both small and large, inhabited and uninhabited, it assumes a agitated mien along a series of channels, some extremely dangerous in parts. Attractive and deadly in these turbulent waters is the Phapheng Falls, 36 kilometres south of Khinak by road -- which we reached after an even more bone-shaking journey than the ride from Pakse. Suddenly, without warning, a deceptively languid arm of the river crashes 15 metres over a rocky cascade into a maelstrom of white water.

A classic waterfall in appearance, Phapheng is intensely picturesque; Somphamit Falls, is not. Located upstream on a different branch of the river at the northern edge of Khone Island, it is set amid a mass of jagged rocks. Here the Mekong forces an angry

passage in a series of cascades as opposed to Phapheng's single drop. It was thrilling enough now at low water, but my guide described an awesome sight in the rainy season when it throws up sheets of spray to the accompaniment of a continuous thunderous roar.

A classic waterfall in appearance, Phapheng is intensely picturesque; Somphamit Falls, is not. Located upstream on a different branch of the river at the northern edge of Khone Island, it is set amid a mass of jagged rocks. Here the Mekong forces an angry

passage in a series of cascades as opposed to Phapheng's single drop. It was thrilling enough now at low water, but my guide described an awesome sight in the rainy season when it throws up sheets of spray to the accompaniment of a continuous thunderous roar.

At the same time as marvelling at a wonder of the Mekong, I couldn't help being unnerved by this inhospitable face of the river. It was not difficult to share the utter despair the sight struck in the hearts of Doudart de Lagree and Francis Garnier, leaders of a French expedition up the Mekong in the 1860s. Their glorious but vain hope was to discover a river road to China that would have made the French Indochina colonies so much more valuable.

Never an easy river to navigate above Phnom Penh, the Mekong is impassable at Khone. Garnier and Lagree did, with great difficulty, managed to haul their small boats up one of eastern channels at Somphamit and then, to the horror of their Cambodian boatmen,

they chanced the westernmost channel only to find themselves caught up in a dangerous white water race. They were forced to admit that no commercial river craft would ever pass this barrier.

Standing where French dreams had been shattered, and remembering my travels upstream, I could only agree with Garnier's generous description of the Mekong which had beaten him:Without doubt, no other river, over such a length, has a more singular

or remarkable character.

The Mekong River is the major north-south commercial artery; all but two sections of it--the Khone Falls and the rapids of Khemmarat (Khemarat)--are navigable for at least part of the year. Large barges ply the deeper sections of the rivers between towns, but most of the water traffic is carried in smaller craft. Some of the mountain people build bamboo rafts and float their goods to market, selling the raft along with the goods. During French rule, a primitive network of roads was created. The main artery joined Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam) with Louangphrabang, and several lesser roads led eastward through mountain passes into Vietnam. During the Vietnam War, road building and improvement were undertaken by the United States, China, and what was then North Vietnam; the best-known of these works was the Ho Chi Minh Trail, a complex of roads, fords, and ferries in the Annamese Cordillera. Laos itself has no railway system, but Thailand's railways funnel goods and passengers to Laos. Small aircraft came into use during the war, and some inhabitants of Laos flew in airplanes before they had seen an automobile. Vientiane has an international airport.

The Mekong River is the major north-south commercial artery; all but two sections of it--the Khone Falls and the rapids of Khemmarat (Khemarat)--are navigable for at least part of the year. Large barges ply the deeper sections of the rivers between towns, but most of the water traffic is carried in smaller craft. Some of the mountain people build bamboo rafts and float their goods to market, selling the raft along with the goods. During French rule, a primitive network of roads was created. The main artery joined Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam) with Louangphrabang, and several lesser roads led eastward through mountain passes into Vietnam. During the Vietnam War, road building and improvement were undertaken by the United States, China, and what was then North Vietnam; the best-known of these works was the Ho Chi Minh Trail, a complex of roads, fords, and ferries in the Annamese Cordillera. Laos itself has no railway system, but Thailand's railways funnel goods and passengers to Laos. Small aircraft came into use during the war, and some inhabitants of Laos flew in airplanes before they had seen an automobile. Vientiane has an international airport.

Laos is a fascinating country which combines beautiful

green countryside and nice rivers with cities that have

a distinct French colonial feeling, as well as an Asian

one. The Lao people are proud of their independence,

warm and friendly to westerners. Laos has many hills,

and in them live people, known as hill-tribe people,

who are neither Lao, Thai nor Burmese. They speak

their own languages, and live by raising livestock, or

growing crops like rice (and sometimes opium).

Most of the hill-tribe people originally came from

southern China. Some of these people make brightly

colored clothes, or jewelry, which they sell.

In the 1950s and 1960s, the illegal opium trade in Laos

, Myanmar, and northwest Thailand earned the area the

nickname Golden Triangle. The regional economy was weak

, and farmers in the highlands had little choice but to

produce poppies many of them golden in color for the

drug trade. Since the early 1970s, however, with the

help of the Thai and United States governments and the

United Nations (UN), many farmers have switched to

legal export crops and have joined Thailands market

economy.

Laos is the world's third-largest producer of opium. The notorious "Golden Triangle," defined by Laos, Burma, and Thailand, provides 60% of the world's heroin supply. Opium growing is associated with the hilltribes that descended from southern China, particularly the Hmong and Mien. The opium poppy is grown all over northern Laos, even on steep slopes and in poor soil, and cash returns are high. Some hilltribes use opium in traditional medicine. There is significant opium addiction in Phong Saly, Hua Phan, Luang Prabang, and Xieng Khuang Provinces. Most opium in Laos is smoke--nearly all refined opium is earmarked for export.

The opium poppy (Papaver somniferum) is one of more than 250 species of poppy. When the petals fall, the seed pod is sliced to release a milk-white juice that dries to a brown fudge that can be stored for years without losing its potency. The brown substance can be refined into heroin for easier transport--there are thought to be hidden labs in the north of Laos that handle this process. Opium is grown in 10 Laotian provinces (marijuana is planted in provinces along the Mekong River). The annual opium yield in Laos is upwards of 200 tons (puny compared to Burma, where annual production is estimated at over 2,200 tons). Some is used locally by hilltribe addicts; the rest is smuggled through to Thailand or China. Opium and heroin are used in bartering for Thai consumer goods. According to an official report by the National Commission for Drug Control, Laos seized 53 kg of heroin, 292 kg of opium, and 9,402 kg of marijuana in 1994. Most of the heroin was intercepted at Vientiane's Wattay Airport; the cannabis was seized in Savannakhet Province.

The opium poppy (Papaver somniferum) is one of more than 250 species of poppy. When the petals fall, the seed pod is sliced to release a milk-white juice that dries to a brown fudge that can be stored for years without losing its potency. The brown substance can be refined into heroin for easier transport--there are thought to be hidden labs in the north of Laos that handle this process. Opium is grown in 10 Laotian provinces (marijuana is planted in provinces along the Mekong River). The annual opium yield in Laos is upwards of 200 tons (puny compared to Burma, where annual production is estimated at over 2,200 tons). Some is used locally by hilltribe addicts; the rest is smuggled through to Thailand or China. Opium and heroin are used in bartering for Thai consumer goods. According to an official report by the National Commission for Drug Control, Laos seized 53 kg of heroin, 292 kg of opium, and 9,402 kg of marijuana in 1994. Most of the heroin was intercepted at Vientiane's Wattay Airport; the cannabis was seized in Savannakhet Province.

The opium trade was once legal in Laos. The practice of growing opium was forced upon the Hmong by the French government of Indochina, which secretly sold opium to Marseilles gangsters to finance the war against the Vietminh. Later the CIA became involved in the trade, using the profits to finance US operations in Indochina. Opium dens were permitted until the Pathet Lao takeover in 1975. These were small places, similar to a country pub, where patrons would drop by for a few pipes. In 1975, Vientiane featured 60 licensed dens, and a lot more unlicensed houses. There is some evidence that even after 1975, Lao Army elements and provincial officials continued a clandestine role in opium and heroin production to ameliorate the disastrous financial situation of the late 1970s and 1980s.

In 1990, Laos agreed to cooperate with the US and UN in narcotics control. The main thrust of the program is to substitute cash crops like coffee or mulberry trees for opium poppies. There have been arrests of drug traffickers, but in the unruly Golden Triangle, enforcement is difficult. The Counter-Narcotics Unit, Laos' enforcement agency, was set up in 1992. It employs only 26 officials and relies heavily on foreign support.