THE EDUCATION OF ROSE DAWSON: PART

II

Chapter Six

Retrospection

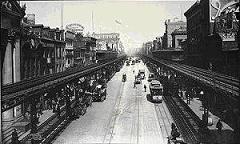

Ten minutes later, they reached the intersection with The Bowery and decided to turn south. The progressively familiar elevated tracks

also ran along The Bowery, which became Third Avenue about half a mile to the

north. Here, the tracks were situated above the sidewalks on both sides of the

street rather than in the middle. Soon after, a Third Avenue El train rumbled

overhead. Rose studied its passing with some interest because it passed so

closely by the buildings that its passengers might have been able to reach out

from its windows to touch anyone in a building trying to do the same.

The Bowery looked like its best days

were behind it, judging from the number of missions in the neighborhood,

including one from the SA, to assist the needy. It was definitely not as

densely populated as the Lower East Side. There were, however, still businesses

that lined the blocks to cater to residents in the area.

At the corner of Grand Street was a

building that stood out from its neighbors due to its classical architecture,

which somewhat resembled the Union Square Savings Bank. This was also a bank –

the Bowery Savings Bank. “Something

interesting, Rose?” asked Jenny.

Rose kept staring at the bank as she

answered Jenny: “It seems that every bank is inspired by Greek or Roman

architecture.”

(L) The Bowery in the early

1900s; (R) The Bowery Savings Bank (130 Bowery)

(The bank was designated

a landmark in 1966.)

“That’s easy,” interjected Amsterdam.

“Banks think they rule the world, and so did the Greeks and Romans.” Rose

smiled approvingly at his simple explanation before she returned her attention

to the bank. She saw the Roman numerals chiseled on both sides of the

building’s façade: MDCCCXCIV, or 1894. This

building is a year older than I.

“Do you know who

designed this bank?” Amsterdam tested Rose.

“No, I do not.”

“Why, that

philanderer Stanford

White. Ever heard of him?”

The name sounded

somewhat familiar to Rose. “Didn’t he design Pennsylvania Station?”

“No, but his

partner did.”

“Oh, that is right,” remembered Rose. Her father had told her that Pennsylvania Station was designed by Charles McKim, who, together with White and William Mead, formed one of the premier architectural firms in the U.S. at the time. It was another Romanesque masterpiece where Rose and her family arrived during their trips by train to New York after it opened in 1910. Sadly, it was on one of those trains where she first noticed her father display signs of the heart disease that would kill him a year later.

“We sat near another of White’s designs yesterday

– the Washington Square Arch,” Amsterdam added. “He also designed Madison

Square Garden, where Evelyn Nesbit’s husband killed him six years ago. He had

an affair with young Evelyn.”

Evelyn

Nesbit. That was another name with which Rose was vaguely familiar. “Yes,

she was an actress, was she not?”

“More like a showgirl,” said Jenny.

“I’ve seen plenty of those in my lifetime, but now I hear she’s a silent film

actress.”

“Interesting.

Didn’t her husband go by the name of Thaw?”

“That’s right – Harry Thaw,” said

Amsterdam. “The scoundrel then pleaded insanity and was committed. He’s a loon,

that’s for sure, but White was no angel, not when he chased after other men’s

wives.”

So

that was why he was killed. Rose had never learned the details of White’s murder from

her family because Ruth did not want her daughter to hear of such barbaric

behavior by fellow members of the upper class. Still, a little bit of hearsay

got through – from none other than Cal himself. Even if he did not want to

emulate Thaw’s instability, Cal could not help but marvel at all the times Thaw

got his way. That made a strong impression on him, and it showed when he tried

to match Thaw’s success on board Titanic

– with tragic results.

“I assume you did not have that problem

with women,” she said sympathetically to Amsterdam while smiling at Jenny.

“Rose, I’ve made many mistakes in this

life and I don’t care if God never forgives me for any of them, but I’ve

followed the Tenth Commandment ever since I married my wife.” Amsterdam put an

arm around Jenny.

“It seems to

have worked well for both of you.”

“It has,” said

Amsterdam.

“But it’s had

its moments, too,” said Jenny, rolling her eyes again.

*****

Like the Lower East Side, The Bowery

contained a large Eastern European population, but there were also many

Italians living in the area. A third group – the Chinese – had also established

a significant presence here, especially four blocks south of Grand Street.

Their numbers, while smaller than those of the first two groups, were more

concentrated. The area continued to arouse Rose’s interest. Prior to this day,

she had only been to the southern quarter of Manhattan just once – when she

went to City Hall as a little girl to meet the mayor. So mesmerized was Rose by

this neighborhood that she bumped into Jenny because she forgot to look in

front of her as she walked. “Oh! I am sorry, Jenny! Are you all right?”

Jenny recovered

quickly. “Not a scratch, Rose. You must be new to this part of Manhattan.”

“I am. I have only been south of

Washington Square Park once, but I vaguely remember it. This area is like

nothing I have ever seen before.”

“I know the feeling,” said Amsterdam.

“The same thing happened to me after I went uptown for the first time to the

wealthy areas. It was a shock.”

The three soon entered the heart of

Chinatown after they turned right on Pell Street. The area instantly became

foreign to Rose, who noticed that all business establishments had their signs

written in Chinese or a combination of Chinese and English. It was the first

time she had seen a Chinese face since she was on the Carpathia. Many of the locals dressed differently – usually a blend

of Chinese style loose, pajama-like clothing and cheap Western style suits and

hats. A few Chinese eyed her with a mixture of curiosity and suspicion.

Moreover, most of the Chinese on the street were men. “Why is that?” she asked

Amsterdam and Jenny.

“It’s a long story, Rose,” explained

Amsterdam. “I’ll tell you about it later.” They continued to walk down Pell,

which was barely two blocks long. Rose continued to study the neighborhood with

interest. On her right, at 24 Pell Street, was a restaurant that oddly called

itself Chinese Delmonico. She had to give its sign a second look to make sure

she read the name correctly. Delmonico’s?

Over here?

They soon reached Mott Street. After

making a left, they walked for half a block before making a quick right at Park

Street. Then they walked down this narrow street until they reached Mulberry

Street. On one side was a park. Amsterdam stopped and pointed to a spot on the

far side of the park. “That was where the Five Points used to be.”

He led the women to the southwest corner

of the park, which was the corner of Baxter and Worth Streets. “Back then, Park

Street was called Cross Street and extended down to here – forming the Five

Points. There was no Columbus Park at the time. The whole area was a filthy,

disease-ridden slum…but it was where we Irish and a few others lived, worked,

played, loved, fought, grew old, and died.”

“It was home,”

said Rose.

“Yes, it was.

Come on. Let’s find some seats in the park first.”

Columbus Park circa 1912

*****

They found an empty bench inside

Columbus Park and occupied it, after which Amsterdam continued with his tale.

“After I left Hellgate, I came straight down here to the Old Brewery.” He

indicated a spot where the brewery used to stand. “I’d been gone sixteen years.

By then, it had become a mission. But I remembered the layout of the building

so I could retrieve this.” He pulled out a large silver medallion he wore under

his shirt and showed it to Rose. “My father gave this to me just before he

died.”

“It is big,” remarked Rose as she

studied the medallion. Not as heavy as

the Heart of the Ocean, of course, but not as much of a dog collar. “Is

there a name for this piece?”

“St. Michael the

Archangel, who cast Satan out of Paradise.”

“You must have had

a strict Catholic upbringing.”

“My father was a

priest – a priest who had a son and became a fighter.”

“A fighter like

you?”

“More like the

other way around.”

“Oh, that is

right. Did your father…die a natural death?” Rose asked carefully.

“No, he was

killed in battle,” Amsterdam answered unhesitatingly.

“During the

war?”

“No, well before the war – in 1846,

actually – here in the Five Points. He was the leader of the Dead Rabbits, an

Irish gang, and they fought pitched battles right there in old Paradise

Square.”

The concept of gangs was alien to Rose,

who never had to deal with them in her former life. “So, he died while fighting

with another gang?”

“Right. I was only seven back then. We

Irish was always getting put down and picked on by the Native American gangs.

So we fought back by forming our own, with my father as its leader. At last, we

had a fist to go with a voice. But after Bill the Butcher killed my father, our

unity began to crack and life for the Irish in the Five Points grew worse.

Since I had no mother, Bill sent me to Hellgate.”

“Was Bill the

Butcher one of those Native Americans?”

“Yes. Real name was William Cutting,

which made sense because he probably cut more flesh than anyone in New York.

When he wasn’t chopping up people on the streets, he was chopping up meat in

his butcher shop. And he was the best knife thrower I’ve ever seen.”

“Better than you

were yesterday?”

“Yes, and I have

a scar to prove it,” said Amsterdam as he tapped his belly. “So does Jenny.”

Rose turned to Jenny, who indicated the

scar on her neck, which Rose first spotted three days earlier at Union Square

Park. “And how did you get that, Jenny?”

“Bill would put on shows to demonstrate

his throwing skills,” said Jenny. “He used me as his assistant and cut me just

this once – to bait Ammie.”

Rose uneasily

felt her own throat. “He sounds like someone to be feared.”

“Anyone who crossed Bill became a marked

man,” said Amsterdam, “but he could be chivalrous too. He called my father a

worthy opponent and ordered that he be given a proper burial in Brooklyn. He

even gave to the poor, but never to the Irish.”

“Why did he hate

the Irish so much?”

“He thought we was diluting the purity

of the Anglo-Saxon race and driving down the price of labor. I ran with him for

a while after I got out of Hellgate, waiting for my chance to avenge my father,

and I once heard him accuse us of doing for a nickel what the colored man did

for a dime and the white man did for a quarter.”

“But are the

Irish not white as well?”

“That’s what I thought. I looked at

myself, looked at the Native Americans, and saw we pretty much looked the same.

Why, then, do the Natives treat the Irish like white niggers? Is it just

because we’re Catholic and they’re Protestant? Is it because we speak funny?

We’ve been coming to America for as long as the Anglo-Saxons, so why the hate?

Why does the press treat us like savages?” These were rhetorical questions, the

answers to which Rose waited for Amsterdam to deliver—if he could.

“When I entered Hellgate, the great

Irish exodus to America had just begun. More of us came here because of the

potato famine and poverty in Ireland, while Native American numbers remained

steady. It was a matter of time before the Irish took over the Five Points. It

was our strength in numbers, Rose. By the time I left Hellgate, as many Irish

had left Ireland as stayed there, and all of us was poor. And the poor are

treated the same all over the world – like doormats to be stepped on. It’ll be

the reign of Queen Dick when a poor man can spit in the eye of a rich man – and

get away with it.”

“Who is Queen

Dick?”

Amsterdam smirked. “There is no Queen

Dick. So guess if the poor will ever get that chance.”

I

did very recently, and believe me, it felt good. Hearing

Amsterdam’s brief story about the Irish in America allowed Rose to understand

what Angus meant when he talked about starving while growing up in Ireland.

Angus had also lived in the Five Points after he arrived in the U.S., but left

for safer pastures after a few years. “So, what happened to Bill?”

Amsterdam let out a small smile of

satisfaction. “When I ran with Bill, I even saved him from assassination once

because I wanted that honor for me. I tried twice to deliver him to the Lord.

The first time he was warned by one of my friends, who was jealous that I was

in love with Jenny. I wanted to kill Bill in front of everybody, but instead,

he almost killed me, only sparing me so I would live in shame. And I was going

to when big Monk McGinn, who once ran with my father, reminded me of my

father’s commitment to his people. That’s when I resurrected the Dead Rabbits.”

“Did you later

intend to…kill Bill in Paradise Square?”

“Yes. That’s where he felled my father and

later Monk; I had to return the favor. He agreed to a battle – no doubt to have

father and son die by his own hand at the very same spot. But there was a

problem: the war. It had come to New York.”

“Was New York

invaded?”

“No, but it might as well been. The city

was divided over the war. A lot of businessmen grew fat and rich trading with

the South. Some continued to do so even after the war began. But, as long as

they was paid in greenbacks, they didn’t care. The rest of us might have

supported the war in the first year, but after those coffins started piling up

on the docks, that soon dried up. When Lincoln issued that emancipation paper,

some of us wanted to secede from the

Union. Almost no one wanted to fight to free the colored, especially not the

Irish. Once Lincoln announced that draft, we knew it would fall on the poor,

who couldn’t pony up three hundred dollars to avoid service. So the pot boiled

over and the biggest riot of the war began. Remember I said we was on Ward’s

Island during the Slocum disaster? We

was visiting friends who died in the riot.”

“If the Irish weren’t rioting, they were

fighting the Natives,” said Jenny, who had been largely silent. “It was just

stupid.”

Amsterdam smiled a bit guiltily at his

wife. “Yes, it was stupid of us to wage our personal war when a bigger one had

come to town.” He sighed. “But the headstrong part of me had to finish what I’d

set out to do – avenge my father before I go to California with Jenny. We

almost didn’t make it. Jenny was hurt in the riot and Lincoln sent in the army

to crush it. When those cannonballs exploded over our heads, they didn’t care

who they hit. Rabbits and Natives went down like flies. But Bill and I still

wanted to have it out. We cut each other up before one last cannonball came and

mortally wounded him. And I finished him off.” Amsterdam showed how with a

thrust of his hand simulating a knife hold. “Bill’s blood sprayed all over me,

and I stared down at his glass eye until it closed. That was the same eye I looked

into after he killed my father seventeen years before. I’ll never forget that.

Looks change with time. The hair thins. It grows white. The skin withers. The

teeth wear out. But the eyes never change.” Amsterdam fingered his own pair to

stress the point. “I wanted Bill to see his executioner right before he left

this world, just as he was the last person my father saw before he died. But I

knew from his eyes – and his words – that he took some satisfaction in how he

died because the cannonball took him down, while I applied the coup de grâce.

His last words was: ‘I die a true American.’”

Amsterdam’s mention of eyes reminded

Rose of her words to Mr. Andrews soon after Titanic

struck the iceberg: “I see it in your eyes.” The message they conveyed – much

disappointment and resignation, but no terror – was clear, and they did not

change their expression even when Rose saw Mr. Andrews again as the ship was

clearly tilting. He was prepared to meet his fate. Eyes are a conduit from a

person’s heart. She also recalled Jack’s eyes as he drew her on the couch—as they

penetrated to her soul. His stare would forever be etched into her memory.

She also felt disgusted by the mention

of blood and violence, not to mention strange to be talking face to face with

an admitted killer – but one who had saved her life. That, however, only made

her more interested in Amsterdam’s story. “You admitted it was stupid,

Amsterdam, but was killing Bill…worth it in the end, despite the stupidity and

the death and destruction around you?”

Amsterdam took a deep breath and paused

in thought before replying. “That’s a good question. At the time, I only wanted

revenge, and I had to pursue it because I’d challenged Bill to the fight. If I

backed down, my fellow Rabbits would see me as a weak leader who couldn’t

follow in my father’s footsteps, and Bill would be even less forgiving. If I

didn’t kill him, he’d kill me. At the time, I didn’t worry about what came

after that, but everything else soon caught up with me. I never expected things

to get so out of control with the riot.”

Just like after the iceberg hit.

“None of us did,” Jenny chipped in. “The

riot gave people the excuse to release their anger at anyone or anything they

didn’t like – the war, the rich, the colored people in the city. They even went

after the colored children by burning down an orphanage on Fifth Avenue. It was

hideous.”

Rose grimaced in horror. “How could they

prey on children like that? It did nothing to address their grievances and only

made things worse.”

Amsterdam shook his head in concurrence.

“And I plead guilty to making things worse. One of my Rabbits, Jimmy Spoils,

was a colored. I couldn’t let him join the battle because the other Irish gangs

didn’t want a Negro fighting with them. It was my best chance to get Bill, so I

agreed. It turned out to be my last chance. The riot and Lincoln’s response

devastated the city. We later found Jimmy’s body laid out on a street. He’s

lucky the mob didn’t torch him because they burned a lot of colored that day.”

Amsterdam sighed again. “Maybe I should have had Jimmy sneak into the fight

once it’s underway, but he probably would have been killed either way. But at

least he would have died with friends.”

Rose shook her head in sorrow. “That was

another of your tough decisions.”

“It was, but even if we hadn’t fought,

Lincoln would have still called in troops to put down the riot. Most of them

had suffered badly at Gettysburg and wouldn’t have looked too kindly at some urban

rabble who shirked military service. We intimidated the army’s recruiters and

they wasn’t about to forget that. So, fight or no fight, the Rabbits and

Natives was finished.”

Aftermath of the New York Draft Riots, July 1863: (L) Body

of Jimmy Spoils displayed on a street;

(R) Amsterdam and Jenny survey the damage to New York from

Brooklyn

“I never knew that New York was once

like this,” exclaimed Rose, who seemed to grow more surprised with each new

revelation by Amsterdam. No one in my

family ever told me about the riot, and for good reason.

“Today’s New York ain’t the New York of

old, Rose. Everything – or almost everything – we knew was mightily swept away

as if we was never here. After Jenny and I buried Bill next to my father in

Brooklyn several days later, we could still see the smoke from the ruins across

the river. That’s how long New York burned. I don’t know how many died in the

riot. Official counts say just over one hundred, but I saw that many bodies

tossed into just one mass grave. I’m willing to bet my medallion there are more

bodies which haven’t been found yet!”

Rose was again repulsed by more mention

of death and destruction. All of a sudden, as if telling everyone to break for

intermission, the sky began to precipitate, forcing Amsterdam to cut short his

autobiography. “Let’s go find some shelter before I continue,” he suggested.

The three left Columbus Park and walked back up Park Street before turning on

Mott.

“I hope we didn’t scare you with these

stories,” Jenny whispered to Rose as they walked behind Amsterdam sharing

Rose’s umbrella. “We’ll stop if you want us to.”

“I am all right, Jenny. You and your

husband must have faced many unpleasant experiences and want to share them with

someone else who understands, so please continue to speak freely.”