THE EDUCATION OF ROSE DAWSON: PART

II

Chapter Eight

Acculturation

Rose followed

After leaving

the butcher shop, they went several stores down to a vegetable stand, where

Jenny picked out some carrots, potatoes, and two types of vegetable Rose had

never seen before. Then they continued south on Mott until it ended at a

junction of streets called

They slowly

crossed

Manure.

This time, Rose

caught sight of a small pile of it next to a fire hydrant just as she stepped

on the curb after crossing to the southeast corner of

Jenny was the

next to spot her misfortune, and she reached for her canteen again, only to

find that no more water remained inside. There was also no grass on which to

step.

Fortunately for

Rose, the rain had left some fresh puddles in the sidewalk’s shallow craters.

“Try cleaning your shoe in one of them,” suggested Jenny. Rose followed her

advice, and most of the droppings washed off. “We’ll take care of the rest at

home,” said Jenny.

I never imagined that walking the streets of the

*****

They continued

east until they reached a narrow passage called

“Hey, Vallon!”

The three turned

to see a large colored man – half a head taller and perhaps half again as thick

as

“Yeah, I saw it

happen from all the way across the street,” said Sam jovially as he looked at

Rose, who blushed, but soon recovered.

“How do you do, Miss Dawson?” said Sam as he extended his big hand

to Rose.

Rose gracefully

shook Sam’s coarse and beefy hand, which had evidently endured much hard labor.

“Quite well, Mr. Cole, if you discount this recent misfortune. But please call

me Rose.”

“Only if you call me Sammy.”

“All right, then, Sammy.”

“How’s the shoe?”

“It will survive, I think.”

“Of course it

will. You was lucky, Rose, believe it or not. That

must have been left by some stray mutt, but many dog owners let their animals

do it, too. The streets here are filthy, but cleaner than twenty years ago,

when they was filled with that stuff. People just

tossed it out their windows and sometimes hit you in the face. Children even

played in it.”

Rose flinched at

Sam’s depiction of such seemingly uncivilized behavior. Life is rather different in the

“Sammy’s worked

as a street cleaner, so he’s seen it all,” explained

“That’s how I

treat all my elders – like my mama taught me,” said Sam before he turned to

greet Jenny. “And how do you do, Mrs. Vallon? How’s

the face right now?”

“Not much different from this morning,” quipped Jenny.

“Rose is quite

new to the city. Jenny and I was of some help to her

yesterday,” said

“You mean the

fight at

“Sammy’s also a

semi-professional boxer,” said

Jack again. “No, I did not

know that,” confessed Rose as she continued to eye Sam politely. “You would

have made a wonderful ally, Sammy.”

“And I owe it

all to Vallon right here. He taught me many moves.

You saw him fight yesterday. He’s good!”

“He most certainly was,” said Rose, looking at

Sam sized up Rose. “Hmm, I don’t know, Vallon.

What you think?”

“I saw Rose punch the trickster. She’s got potential, but first,

she needs to improve her footwork technique.”

As usual, Jenny issued a light slap to her husband’s arm to get

him to stop teasing Rose. “We’re inviting Rose over for supper. Care to join

us, Sammy?”

“Not today, Mrs.

Vallon. I have to help someone move something. But

I’ll be sure to stop by and check on yous tonight.”

*****

They continued

down Catherine as Sam went in the opposite direction. Two blocks later, they

turned east on

(L)

“April showers

will bring May flowers,” assured Rose. Just as she had finished speaking, a

large cockroach darted past her feet and out the door. Just like her encounter

with the rat in Titanic’s Third Class

general room, she jumped back at the sight of this critter. But this time, she

did not scream in terror. The only voice to be heard was that of

Still,

“Yes, and I am

sure it will not be the last,” replied Rose, as she recovered pretty quickly.

“Don’t worry

about them. Next-door neighbors just moved, so they come over here to look for

food.”

Rose studied the

apartment. It was very small – not much bigger than her bedroom in

Jenny told her

to take off her shoes before leading her to the toilet in the back of the

apartment, after which she took Rose’s dirty shoe to the bathtub in the kitchen

to give it a thorough cleaning. After Rose finished her business, she returned

to the kitchen and examined the tiny apartment in greater detail. The most

unusual feature was obviously the location of the bathtub.

“Now that’s a real convenience,” said Jenny, aware that Rose was

transfixed by the bathtub.

“A bathtub in the kitchen?”

“No,

the indoor plumbing. Better for me to clean your shoe.

We didn’t have flush toilets and wash basins that drained by themselves when I

was your age. The electricity and gas stove are pretty recent, too. And, yes,

the bathtub is nice as well.”

“Would its location here…inconvenience you?”

“Not if you

compare it to the old days of having to go outside to wash and risk being seen

by strangers, or worse. That’s if we washed at all.”

Rose was

slightly taken aback by Jenny’s disclosure that people did not always bathe

decades earlier. This, combined with Sam’s description of how much filthier

*****

“Take a seat,

Rose,” said

Rose sat down

before answering. “The bathroom facilities were…more enhanced.” But life was not always better if you equate

better with happier.

“Things have

improved since we was yer

age, but slowly. Now, they don’t call us Irish a dirty, diseased people as much

as before. They reserve that for those who came after us – the Italians, the

Jews, the Poles, and especially the Chinese.”

“Why

the Chinese?”

“The Chinese was

much like us – fleeing their country in large numbers because it couldn’t feed

them all. When they came, they faced all the prejudice we had to face – and

worse. At least we could blend in with the white population. When times got

tough, and they was tough in the Seventies, many of us

blamed the Chinese, especially in

Alien. That word best described Rose’s perception of the Chinese,

but this stemmed from her lack of practical exposure rather than a deliberate

attempt to shun them. In fact, most of what she knew about the Chinese before

the sinking she learned from reading a couple of Mark Twain’s works: a book and a play, the latter of

which he co-authored. Both made the Chinese seem more like visitors from

another world than fellow inhabitants of this one. Despite Twain’s

progressivism and general sympathy for the Chinese, Rose conjectured that these

works, while interesting, pigeonholed and did not provide an informative

picture of them. They were also not her favorite Twain productions, which was

why she donated them to the university libraries in

“Almost. Some returned to

“Whatever became

of ‘Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses

yearning to breathe free’?”

Jenny, who had

started to prepare supper in the background and had overheard every word of the

conversation, let out an amused laugh. “Shouldn’t it be ‘wretched refuse’?”

“Is there a

difference?”

“No, I guess

not.”

Rose,

despite being unpleasantly surprised at this ignoble act on her country’s part,

found

“If only it was

always that funny,” continued

“The…tongs?”

“Right. Mock Duck’s

kind of people. What the government didn’t understand was that the more it shut

the Chinese out from the rest of society, the more they’ll rely on and enrich the tongs. They’re criminals, for sure, but they know

what their people want. That’s why there are tong wars and people die – to

control the supply of what people want. And in the rare instances the

authorities investigate a crime, say a murder, in

“Does this

contribute to the impression that

“Yes, and that’s

unfair, just as it’s unfair to lump all Irish in as drunks or gangsters. The

press comes out with stories of ‘John Chinaman’ eating rats, smoking opium,

waging gang warfare—” Amsterdam immediately stopped after seeing Rose’s face

turn nauseous at the mention of the Chinese consuming such a ubiquitous pest.

“Sorry, Rose. I

was carried away again.”

Rose gave him an

encouraging smile. “I am fine,

“The saying goes

that the Chinese eat anything that moves and almost anything that doesn’t. If

they do eat rats, how different is that from white country bumpkins who eat

squirrels, which I’ve seen? The two are almost the same, except one has a bushy

tail, while the other has a long, whip-like tail. As for opium – you think

white folks don’t smoke or trade in it? Nonsense! And I don’t have to tell you

about gangs.”

“Yes, I have

read about the Chinese washing clothes here for a living,” said Rose, recalling

what Twain wrote about them. “So, how did their men

find love and companionship?”

“The Chinese can

be quite clever in this regard. Some married white women and even took their

wives’ surnames. Irish women was an especially good

match because there wasn’t enough Irish men in this country. So, bang! A

perfect fit.”

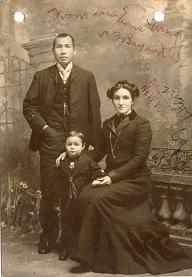

An interracial Chinese-Caucasian family in the

Rose laughed

again. “This is all very fascinating.”

“The Chinese

wish they could say the same. Their heads was filled with stories of gum saan, or

“But why would

some Chinese exploit their own rather than unite with them to fight for a

better life for all Chinese in this country?”

“Money and

advantage, that’s why. And it’s not just the Chinese. We Irish ain’t above preying on our own either, and the rich are

only too happy to let us do that and fight the other groups when we should all

be cooperating. Even the unions pitted the Irish against the Chinese, and many

Irish was only too glad to oblige. This was so true in

“McGloins?”

“Oh, Charles McGloin was once a Rabbit. After my father died, he ran

with Bill even though Bill never fully accepted him. Then he was killed by

Union troops during the riot.”

“And regrettably

so,” interjected Jenny in the background.

“That’s one

reason why we left

“Was there

nothing good about

“I do not know.

Why?”

“Because

Rose was

confused at first, but then realized that

“That’s right.

So what if the weather’s nicer in

There was a

touch of disillusionment in Rose’s face, which Jenny noticed. “Don’t get Rose’s

hopes down like that,” she admonished her husband. “She should still go to

“Well, don’t let

me discourage you, Rose. Saints and scalawags and Mother Nature’s wrath abound

everywhere. Just be careful. I think you’ve heard that many times already.”

“Yes, I have,

but thanks. Clearly your memory of the Five Points also contributed to your

decision to come back.”

“We was a little

homesick, and the Five Points was home, no matter how bad its name.

“How is that?”

“Take Sammy, for

example. He’s the grandson of Jimmy Spoils. Jimmy fathered a daughter before he

died, and that daughter became Sammy’s mother. I didn’t know this until after I

returned to

Rose was awed by

this tale, not only by the reunion that occurred, but also by the length of

time that elapsed between encounters, even if it was only with a picture.

“I told Sammy I

felt responsible for Jimmy’s death because I didn’t let him join us for our

fight. I’d kept this guilt inside me all those years and had to release it. But

Sammy’s so forgiving. He said his grandmother told him everything – it was the

rioters’ fault. I said the fault was mine, but he insisted his grandmother was

right.”

“That was very

generous of him.” Rose stood up and stretched out. “Wow, forty-two years is so

long.”

“It seems that

way when you’re young,” said

“Maybe I can

wait until 1954.” If I

live that long. “Until then, I have to give meaning to each day I am

here in this world, and that means living my life to the best of my ability.”

“I think you

will, but I don’t expect to be around to see most of it.”

“