Route 66 / Do I Have to Cry For You

A Carter-Dorough story, for the Dashboard Confessional Challenge . My assigned lyric:

Buried deep as you can dig inside yourself,

and hidden in the public eye.

Such a stellar monument to loneliness.

Laced with brilliant smiles and shining eyes

and perfect makeup but you're barely scraping by.

Everybody had ‘sad songs.’ Songs, that is, that they used for emotional catharsis when everything had gone to hell.

The Bass, well, he had a jump on most of them anyway. Though Bri ran him a close second. When it came to sad songs, they had a hell of a repertoire to pick from. After all, when it came to angst and broken hearts and that High Lonesome Sound, Patsy Cline was a possession for all time. Lyle Lovett, Robert Earl Keen, and of course Frick’s beloved Bill Monroe; Willie and Waylon; old-style Johnny Cash; Leon Redbone: all could sing the songs of misery and pain with an aching plangency that struck deep to the bone…. Even some of the country and bluegrass gospel songs were mournful, as mournful as a Stabat Mater: ‘Wayfaring Stranger’ and ‘Will the Circle Be Unbroken,’ say. The ‘mourners’s bench’ songs, the hymns of penitence. Country and bluegrass and even Dixieland, sometimes, and their allied styles, worked the dying fall better than almost any genre of music out there.

Except, maybe, jazz. If Chasez wanted to wallow, he could do so with sophistication and a bittersweet edge, simply by cueing up Ellington or Gershwin or, well, Miss Peggy Lee’s coldest despair, colder even than the brittle nihilism of ‘Is That All There Is’ and ‘Fever:’ he’d inadvertently overheard C once, in deep mope, harmonizing hauntingly to ‘Black Coffee,’ and he’d been rendered depressed for days himself. And what misery Billie Holiday hadn’t been able to sing about wasn’t worth bothering with, from lost loves to ‘Strange Fruit.’ Yes, jazz could plumb the depths; jazz and the standards of the American Songbook, and the blues. You could hardly find more emotive music.

Unless, perhaps, it were grand opera and some showtunes. Fatone by rights ought to have indulged misery like a guilty secret: it bewildered him when it befell, and he had his reputation for sunniness to maintain, so that when he needed the release of some human sadness, one might expect that he would so so furtively, like a dieter surreptitiously cosseting a sweet-tooth. But he did indulge it, and he did so without apology. With Sondheim, perhaps. Or with Verdi, or Leoncavallo. Perhaps at some level he thought he could always excuse, if pressed, any tears that welled in his eyes by claiming to be hamming it up, though, Italian-like, he had never in fact felt the need to excuse them: Joey had a Latin freedom from the insecurity about tears (and laughter) that the Anglo-Saxons suffered from. Like his father, Joey was never cowardly about feeling joy and tears alike. But, yes, certainly, opera and the best of Broadway excelled in conveying the depths of tragedy. None better.

Unless, of course, it were the untutored genius of the folk. ‘The “Red State” Three,’ as Kev and Aidge called them, had teased Kev mercilessly about what a shame it was that he’d not had a part in A Mighty Wind, but there was salt to the jest, a grain of truth. Brian, as he grew into himself, husband and father and responsible adult, had come more and more to cherish the gospel music into which his ancestral bluegrass imperceptibly shaded, whilst his cousin had moved in another direction, sometimes complementary, sometimes contradictory: to folk music, and not infrequently to protest music and folk-activist anthems. (The Bass had called him ‘Joe Hill’ once, which had set off a solid, interesting uproar that lasted a good three-quarters of an hour.) But John Prine’s ‘Paradise’ clearly affected Kev on a deep level that was not explained solely by its slams at ‘Mr Peabody’s coal trains;’ nor was it ideological kinship that made him a fan of Joan Baez and Ricki Lee Jones. And, although an ‘Aragon Mill,’ or Leadbelly’s ‘Midnight Special,’ could be justified by its Message, there was no very obvious political statement involved in Kev’s choking up over ‘Barb’ra Allen,’ or ‘Pretty Saro,’ or ‘Careless Love.’ What was certain was that this was music as moving and heart-wrenching as any.

But then, the capacity to tug at heartstrings was not, after all, limited to any one genre, after all. What the anonymous balladeers of the Midlands and Appalachia, of the Lowlands and Connaught, could accomplish, even Tin Pan Alley and its modern successors in commercial pop could sometimes achieve. Before rehab, AJ would have split a gasket had anyone let slip his secret, but since he had been in recovery his bad-boy pretensions had been increasingly abandoned as the self-destructive self-parody they had become. He could still rock out with the baddest of bad-asses, but he wasn’t any longer pretending that that was all there was to him. The fact that a mix CD of Bruce Hornsby, Billy Joel, and Elton John at their most melancholy could reduce Aidge to sodden catharsis was not something anyone publicized, but AJ was no longer in the least ashamed of it. Nor, after all, did he need be: unquestionably even these slick commercial productions were tinctured with lacrimæ rerum.

It was a funny thing, really, that for so many of them, the music they turned to in sad times conformed to at least a part of their carefully crafted images, although it was in those instances the portions of those images that had some roots in their real selves: Bass’s country, Bri’s bluegrass-gospel, JC’s jazz, Joey’s broadway and Italian opera….

But the rule wasn’t universal.

If it was little enough surprise that Justin had long tended to transmute sorrow into anger and lashing-out – the phrase ‘cry me a river’ had for some time summed up his attitude towards emotion – it was rather more noteworthy that he was maturing in this respect as in others. And it came as something of a surprise to find that, aside from the predictable resources of the more melancholic mode of R&B: Toni Braxton, Brian McKnight: and in addition to his increasing interest in New Age music (Chris had commented that the Brit Situation had improved Narada’s PE ratio and Amazon.com’s gross for an entire quarter), J actually deserved credit for having set himself to learn something of the actual blues that underlay so much of what he loved and lived and did. It was almost surreal, hearing Timberlake discuss – with no little learning – Robert Johnson and Robert Cray, Etta James and Big Mama Thornton.

The only thing predictable about Chris, as he had long known, was that Chris was unpredictable, eclectic. For Chris, in many ways, sad songs were simply songs accidentally attached to bad memories. But he also knew what sadness inhered in music, from Edith Piaf to the Solitaires to the Harptones to the Five Satins to Smokey and the Miracles to some of the Mills Brothers’s tracks, to Rush and the Clash, to Soft Cell and the early Pet Shop Boys. (Not, come to think of it, that it was truly surprising that CK could reel off the entire ‘sad songs’ playlist for doo-wop or the Eighties….) And the loss of Dani had done a number on Chris: there was a time, agonizing to all of them who loved him, when Chris, who had once tried to prove that man could live by snark alone, had been, emotionally, no more than a walking scar, and had lost himself in emo for anodyne.

And as for himself? The jíbaro, the peasant, dirt-farmer, countryman in any culture, knew and lived the blues, from PR to the Mississippi Delta to the hardscrabble hollows of Appalachian Kentucky. And he would back the lush melancholy of good danza against any music out there: it didn’t require patriotism or even knowledge to get a catch in the throat when you heard, when anyone heard, even all unknowing, La Borinqueña, surely, and there was plenty of blues (as well as all other emotions of the human condition) in décima. And as for plena, well, el periodico cantado had its share of bittersweet themes.

But when it came right down to it, the Doroughs were Kerrymen, Irish to the backbone, Kerrymen since the Fir Bolg were ass-whupped by the Milesians, and he would back his father’s people for heartbreaking music over anyone anywhere. The Irish were masters of misery.

The point was…. Well, the point was, it had just been unexpected. That was all, truly, whatever it seemed. Even if he himself, and Chris, and J, could be classed as a little less predictable than Brian and Kev, Joe, Aidge, and the Bass-Chasezes, still their choices in melancholy music were comprehensible. He hadn’t been laughing at Nicky. He never had, he never would, except when it was a joke Nicky got, too: he knew how valuable to Nick his unconditional support was.

But it had taken him by surprise, and his laughter was involuntary. It hadn’t been laughter at Nicky; if anything it had been laughter at his own surprise and his own ignorance. But Nick had taken it, naturally enough, as directed at him.

He had tried to explain. It was the incongruity that had startled that bark of laughter out of him. The incongruity of Nicky: the Nicky who was flaunting the influences of Bon Jovi and Bryan Adams, the Nicky for whom, surely, power ballads were the most ‘sensitive’ music he cared to admit to, for whom the limit of musical melancholy doubtless went no deeper than, in Bass’s own genre, did the sardonic ‘London Homesick Blues,’ Nicky the born-again retro-rocker: the incongruity of Nicky proclaiming how much emo moved him, and talking about it with Chris as one informed, old-hand fan to another, had whipsawed Howie.

That was all. But Nick had not stayed to hear his contrition.

What made it worse was that Howie knew that it had been his unthinking and unintentional laughter that had tipped the balance. Jane was of course a chronic heartsickness. What Jane did and could do to Aaron’s life, and what Nick’s other siblings were managing to do to their own lives even without her malign interference, tied them all in knots. And the uncertainties that still loomed over the group’s future and could not be dissipated had them all on edge. Yet Nicky, despite these things, despite Jive’s screwing him as thoroughly as Jive was screwing their friend Chasez, despite sales numbers and unceasing family dramatics, had been happy, free at last. Until Howie, the one person in his life he could count on, had seemed to mock him. Howie had barely had the chance to get used to this golden, happy Nick, eyes star-brilliant with gladness; and now, by his own, fatal inadvertence, that shining moment was gone, and Nick with it, back on the road.

And that was not to be suffered. That they had the power to hurt each other so deeply, casually, even by accident, was the reverse of the coin: the obverse was that this was so because of how much they each of them meant to one another. And Nicky’s having betaken himself to the road meant that Howie must follow.

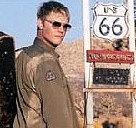

Must, and had. He had flown to California, to find that Nick had been there and was gone. And knowing Nicky so thoroughly, with his heart as well as his mind, Howie had known where next to go. The ghost town of Oatman was behind him, the sun westering in his rearview mirror, dusk coming out of the east to enfold him. The radio was silent, and he would keep it so.

Get your kicks on Route 66.

Just Howie, and the Mother Road, and the dashboard, which could hear his confession but was powerless to grant him absolution whatever penance he undertook. Kingman was before him, its Quality Inn a far cry from the luxury that had lapped their lives for so long, but special in its way, half-motel and half-museum, a noted shrine to the history of old Route 66. And he knew, with a certitude that was based upon no asking and that rose above mere fact and information, that he would find his love there. His Nicky: the troubadour Nick, a little dusty with travel, pared by the road and the glare and the miles beneath the sun, with his guitar slung over his broad shoulders and his backpack, loosely carried in one large hand, thumping against his denim-clad leg. His Nick, his all, hiding in plain sight, hiding within himself as deep as he could burrow. Yet waiting, too, with the same expectation, knowing that the mystic connection between them might attenuate but could never break, knowing that Howie would come to him, would surely find him. Sure that they would both pass this test he had set them, would find each other as the compass needle finds true north.

‘Do you have a reservation, sir?’

‘He does,’ said a voice from behind Howie. ‘For the adjoining room.’

Howie turned around, casually, refusing to doubt their bond.

‘Hey, D.’

‘Hola, compinche.’

Their eyes locked, and not all the declamations of romancing poets could have matched what they said silently to one another in the lobby of a mid-price motel in Arizona.