| Home |

| CHT |

| Background |

| Bengali Muslim Settlers |

| Armed Resistance |

| Massacres |

| Genocide |

| Religious Persecution |

| Rapes & Abductions |

| Jumma Refugees |

| CHT Treaty |

| Foreign Aid |

|

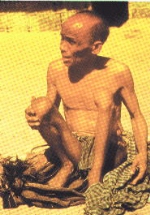

Bangladesh army shot this indigenous Chakma Buddhist on the left thigh in May of 1986. He and his family were heading to the Indian border to escape attacks from the Bangladeshi armed forces and Muslim settlers. They were intercepted by Bangladesh army and shot at. This man together with his family took refuge in Tripura state of India. |

There have been massive and systematic human rights violations in the Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT), committed by Bangladeshi armed forces and Muslim settlers. Indigenous Jumma people have been murdered, crippled, raped, tortured, imprisoned and deprived of their homes and means of livelihood. They have been denied civil and political rights.

Netherlands based Organizing Committee for CHT Campaign reported 278 cases of Human Rights violations committed between July 1985 to December 1985. The human rights abuses include murders, torture, rape, arson, robbery, abduction, forcible conversion to Islam and electoral fraud. The policy of the Bangladesh government had been to destroy the local inhabitants in order to settle its Muslim co-religionist in their place. Torture of the CHT people is carried out by the Bangladesh armed forces everyday. It is so brutal and severe that many of the victims are crippled and most of them die prematurely. Most commonly, the Bangladesh military or paramilitary personnel enter indigenous Jumma villages in the early hours of the morning and take away a small number of able-bodied young men of the village or occasionally the village headman, to their camps. The arrests are undertaken without using any legal procedure such as the presentation of arrest warrants or bringing the arrested person before a magistrate within 24 hours, as the Criminal Procedure Code specifies for arrests by police officers. The Chittagong Hill Tracts had never been officially declared a "disturbed area" so that the provisions of the Disturbed Areas (Special Powers) Ordinance, 1962 - the 1980 Disturbed Areas Bill never had been enacted - had not been invoked. As a result no legal procedures were in force specifically providing for civilians to be arrested by military or paramilitary forces.

1. Military Induced Terror

Indigenous people detained for questioning by the Bangladesh military and paramilitary personnel are regularly tortured. Such prisoners are generally kept in pits or trenches some seven or eight feet deep, dug within the perimeter of the Bangladesh army or BDR (Bangladesh Rifles) camps. Indigenous people have often been compelled to dig these pits in the first instance. One of the two sides of the pit or trench is protected by a fence of bamboo stakes. Prisoners are held in groups of up to 15 or 20 at one time in these conditions. Several former prisoners said that soldiers sprinkled hot water over the pit or trench to increase their discomfort almost daily. Prisoners are then taken out singly from the pit for interrogation. The techniques of torture which former prisoners reported to be most frequently used during interrogation are: extensive beating, with rifle butts and sticks, on all parts of the body; pouring very hot water into the nostrils and mouth; hanging the prisoner upside down, often from a tree, for long periods and poking him with a bayonet or stick; hanging the prisoner by the shoulders for long periods and then beating the soles of the feet; and burning with cigarettes. Over the years, many indigenous people died in custody as a result of the treatment they received. A middle-aged teacher from Laogang village, in the Panchari area, described his experiences to the Amnesty International thus:

"In the first week of December (1985) the army came to my village and said that it was looking for those who train and support Shanti Bahini boys. When they failed to find anyone they caught hold of me and took me trussed up and blindfolded to an army camp where I found that several Chakmas were already present. Immediately the troops and the officer in charge began to beat us up asking for the whereabouts of the Shanti Bahini people. Since we did not know anything we could give them no information. The soldiers then took us to a part of the army camp where a huge deep pit was already present. All the while they were kicking and abusing, spitting at us and shoving with rifle butts. We were all thrown into the pit and for several days soldiers came and threw boiling water at us whenever they felt like having a little fun because whenever that happened all of us tried to get under each other for cover. We were often dragged out individually and subjected to third degree treatment. Boiling water was poured into our nostrils and mouth. For several hours we were hung from the trees upside down and beaten with sticks. Once I was hung from the trees by my shoulders and beaten with cane on the bare soles of my feet. We were given food not more than once a day and were constantly threatened that we would not be allowed to go out alive. All this while I had no contact with my family. It is ridiculous even to suggest that I could have contacted a lawyer and tried for bail. I still have scars of burns from boiling water over my body."

This interview was conducted six months after the teacher's detention. Faint scars on his body were visible to the naked eye but could not be successfully photographed. Other accounts of treatment in army or BDR camps by villagers from other places are markedly consistent with the above account, as is illustrated by the experience of a villager from Rangapani, also in the Panchari area:

"I was arrested by the army who said that I knew about the activities of the Shanti Bahini boys, which was incorrect but they took me away to a military camp near Khagrachari where I was detained along with several other Chakmas in a deep pit. As a routine of almost every day soldiers came and sprinkled boiling water on the pit. We were given nothing to eat but watery dal (a lentil dish) and pasty rice. They took each one of us out individually for torture and questioning. Usually the torture meant severe beating with cane, rifle butts and hanging the man upside down from a tree which made it easy for the soldiers to pour boiling water into his nostrils and mouth. This was done to me three times. Also one afternoon the officer came and poked various parts of my body with a cigarette. I still bear the burn marks on my right cheek".

"When they were unable to get anything out of me, they threatened me with electric shock. I was taken to a room where they had kept a bucket of water in which they had dipped two live wires tied to a razor blade. They stripped me and asked me to urinate in the bucket. They kept on beating me up but even though I tried I wasn't able to do it because of fear. They beat me up till I fell unconscious and threw me back in the pit. All the while we had no way of contacting a lawyer or court. My family had no way of contacting me as well, but they were able to contact (a member of the Panchari Union Parishad - council) who was able to secure my release."

Several former indigenous prisoners had also been threatened with the electric shock treatment. Another villager from the panchari area described the experience of his 27-year-old son during December 1985, when his son had been held for 23 days in Khagrachari cantonment:

"The torture basically was army men throwing hot water into their nostrils and mouth and mercilessly beating. When the army got no information from my son in spite of this, he was subjected to electric shock in the cantonment. The shocks were administered with as crude a device as two naked electric wires which the soldiers touched to different parts of the detainee's body, particularly on the tongue and spinal cord. Hy son was released after I pleaded with the Union Council which intervened."

This villager also stated that one of the people held with his son, Santoshmani Chakma, died as a result of torture. Mass tortures were also meted out to the indigenous people during searches for the Shanti Bahini guerillas and supporters, they are rounded up from their homes and a few of them, often the young men, are picked out and tortured in front of the assembled villagers. The methods of torture cited are the same as those reported to be used regularly on prisoners held in army or BDR camps. One such incident occurred at Monatek village, Mohalchari on 19 september 1984. Police personnel from the Armed Police Battalion (APB) based at Mohalchari are reported to have rounded up the villagers at around 10 pm on open ground near the village. Four men were then said to have been selected from among the assembled group and in front of all the others they were reportedly hung upside down, beaten and had water poured in their nostrils and mouth.

2. Concentration Camps

Torture also used when coercing the indigenous people to move from their homes into collective farms, or "cluster villages". The policy of establishing what were essentially collective farms began in 1964, to encourage tribal people to settle on permanent land plots rather than continue jhum (slash and burn) cultivation. Since around 1977, however, it appears that the settlements to which indigenous people have been moved bear greater resemblance to "concentration camps", since army, BDR or police camps are also established alongside them. The relocation of indigenous people has been presented by law enforcement personnel as being in the villagers' best interests although the implementation of this policy serve other purposes: through the close surveillance of indigenous people, assistance and shelter to the Shanti Bahini can be prevented, while the land vacated by indigenous people may then be used for resettling Muslim settlers from other parts of the country. These "cluster villages" were established throughout the Chittagong Hill Tracts. In early 1986, an effort to intensify the formation of "cluster villages" in the northern parts of the Chittagong Hill Tracts was begun by the law enforcement personnel of Bangladesh. The area affected included villages in the Mohalchari-Nanyarchari-Khagrachari locality. A member of the Marma nationality described the experience of his village, Khularam Para, near Mohalchari:

"On 27 January (1986), about 50 armed men from Hajachara camp, commanded by a captain, raided my village and ordered people to move to a cluster village at Hobachari. The captain gave a speech and said that for our own safety, development and for destroying the Shanti Bahini it was necessary for us to move to larger villages. When we refused they took aside about 20 of my villagers and tortured them in full public view by burning them with cigarettes, beating them with rifle butts and spitting on their faces....Later the village was burnt and everyone ran helter skelter".

Similar abuses were taking place in the Nanyarchari area, according to a villager from Dewan Chara:

"Since the beginning of this year the army and police had been visiting the villages in our area asking people to prepare to shift to a new cluster village. They said it was necessary for us to shift for our development and national security. But we all said no, because these cluster villages are like concentration camps where we have to remain constantly under the eye of the soldiers and where our women are not safe."

"In February, large-scale operations commenced in our region and on the fifth of the month a group of soldiers raided our village. The 0fficer-in-charge abused us and the soldiers who were firing in the air to scare us started to beat us up indiscriminately. After a while they took out about 15 of us and marched us to the Buddha Vihar (Temple). There we were tortured very badly for a long time. They poured hot water into our mouths and nostrils and burned some of us with cigarette butts. We were let off later in the evening when we promised to shift to the new village."

3. Restrictions on Movement, Buying and Selling

The Bangladesh military divides the CHT into three different zones: red, yellow and white. The red zones are the interior of the CHT, the white zones are the areas within two miles of the regional military headquarters where the army is in full control, while the yellow zones are the Muslim settler areas. The following restrictions broadly cover the different zones: In the red zones the most restrictions are imposed on the indigenous people but not on the Muslim settlers. All the indigenous people have to carry an identity card and if they go shopping they have to carry a market pass. The market pass which is headed 'Bangladesh is in my heart" is a means of controlling the quantities of rice, kerosene, oil and other goods which they are allowed to buy. A family cannot buy more than four kilos of rice per person each week. This is checked at all the military posts along the road. People are asked where they come from, where they are going to and their bags are searched. If hill people want to sell some of their produce, such as rice, they have first to seek written permission from the army. A Chakma woman from Khagrachari District was arrested, tortured and sexually harassed by the Bangaldeshi security forces for buying clothes in 1989.

"I went to the market and bought some clothes. All of a sudden a policeman came from behind and caught me. The police asked: 'Why did you buy the clothes?' I said: 'To wear.' Then he took me to jail and started beating me and giving me electric shocks. They kept me one and a half days, tying my hands. Then they transferred me to Khagrachari army camp. They tortured me at the army camp. The army soldiers assaulted me by touching my breasts etc. After five days I was released on the condition that I report there every month. The charge was that I bought clothes for the Shanti Bahini."

One indigenous youth in Dighinala Upazilla told the CHT Commission that his family wanted to sell rice so he could pay the fees for his studies. When the permission came they were allowed to sell only one maund of rice (about 40 kilos) which was not enough to pay for his studies. There is also a restriction on the quantity of medicines that a person may buy and in some places people need permission from the army before buying any medicines. In the south, people need permission to take goods from there to Bandarban. The reason behind these measures is the army's fear that people will give food and other necessities to the Shanti Bahini. In the yellow zones the indigenous people have to carry identity cards, but no market passes are needed. There is however, in these zones too, a restriction on how much medicine they are allowed to buy. In the white zones there are no specific restrictions, but only those which apply throughout the CHT as a whole. These include a prohibition on all movement outside of towns after the closing hours of the check posts and the need for written permission for long trips.

More:

- Unlawful Killings and Disappearances

- Arbitrary Arrests and Tortures

- Reprisal Attacks in the CHT

- Race Riots

- Curtailment of Freedom of Expression

- Military Disinformation Campaign

- Concentration Camps

- Robberies, Extortions and Frauds

- Collaborator Activities

- Military Activities

- Military Backed Organizations

- Military Encampments

- Electoral Fraud

Sources:

- Life is not ours: the Chittagong Hill Tracts Commission

- Unlawful Killings and Torture in the CHT: Amnesty International, 1986

- Survival International Report

- The Chittagong Hill Tracts: Militarisation, Oppression and the Hill Tribes: Anti Slavery International, London, 1984

- Jana Samhati Samiti Report

comments powered by Disqus