Is Belief in Animal Consciousness Properly Basic?

Searle (1998) rejects attempts to infer the existence of conscious states in animals as vestiges of a dualistic mindset, according to which we must infer hidden mental causes from an individual's outward behaviour. Our belief in animal consciousness is a properly basic belief:

[I]t doesn't matter really how I know whether my dog is conscious, or even whether or not I do know that he is conscious. The fact is, he is conscious and epistemology in this area has to start with this fact (Searle, 1998, p. 50).Allen (2003) criticises this position on the grounds that it fails to settle in practical terms the question of which non-human animals possess consciousness and which ones lack it (the Distribution Question). Where does one draw the line? As a biological naturalist, Searle is confident that science will one day tell us how lower level neural phenomena cause consciousness, and that when we know the "electrochemical" formula for the necessary and sufficient conditions for consciousness, we shall be able to apply it to difficult cases like snails (1998, pp. 45-47). Allen (2003, pp. 7-8) thinks it unlikely that such a formula will yield clearcut answers, and in the meantime, we have to make practical moral decisions as to what kind of legal protection we should accord different kinds of animals. Searle's non-inferential approach is incapable of telling us how to proceed here.

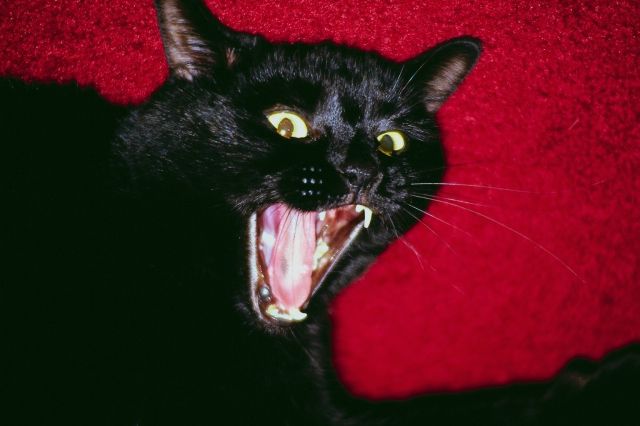

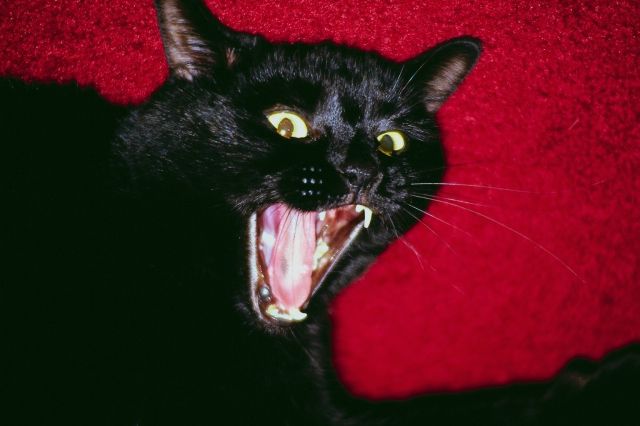

Nevertheless, I would argue that for a small number of companion animals, Searle is right. What I am proposing here is a transcendental argument, which takes as its starting point a fact of everyday life: the fact that we can befriend certain animals such as cats and dogs. The animals I have in mind here are those that have been our companions throughout human history. To affirm this friendship is to affirm the conditions that make it possible - including the fact that they are phenomenally conscious. (There can be no friendship without the possibility of sharing mutually enjoyed experiences.) But it does not follow from this that most other animals (e.g. hippopotamuses) are conscious.

Conclusion 4.31 For a very limited number of animal species (e.g. cats and dogs), the belief that their members are conscious is properly basic.