In this chapter, I discuss the question of which animals are phenomenally conscious, and which animals have higher-order mental states. I endeavour to show that only human beings possess moral agency.

I argue that the conceptual distinctions between different kinds of consciousness, formulated by philosophers, may or may not be real ones, and that philosophers have overlooked a number of nomic connections between consciousness and certain physical states, which can tell us which animals do and do not have consciousness.

Regarding conscious feelings, I contend that most philosophers have been looking for them in the wrong places. Animals' reactions alone cannot unambiguously manifest consciousness on their part, and even intentional agency is not a sufficient condition for its occurrence. However, I argue that a special kind of behaviour by animal agents, namely hedonic behaviour, does require a first-person account. Utility theory allows us to apply first-person concepts to non-human animals (Dawkins, 1994; Berridge, 2001, 2003a, 2003b), but I propose that phenomenal consciousness in animals can be identified unambiguously by affective distortions - by which I mean the kind of emotional mis-judgements that only a creature precoccupied with its own welfare would make. Recent research by Cabanac (1999, 2002, 2004) and Panksepp (1998, 2003) points to ways of measuring these affective distortions.

My specific proposal is that because consciousness can alter human beings' perceptions of risk (Slovic, Finucane, Peters and MacGregor, 2003), it should be possible to identify erratic behaviour in animals blinded by their feelings, which reflects their faulty risk assessments of events in their environment.

The available behavioural evidence suggests very strongly that birds and mammals - and possibly reptiles - do indeed possess subjective states or phenomenal consciousness. (The case for affective states in other animals is much more problematic.) This finding clashes with the opinion of many neurologists, that even simple consciousness is confined to mammals, but I argue that the grounds commonly adduced for this mammalocentric view are not conclusive, and that mammals and birds share a number of neurophysiological features. We can be reasonably sure that all mammals and birds are phenomenally conscious.

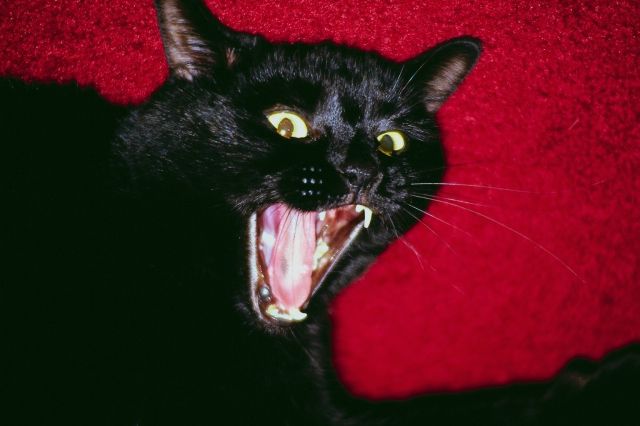

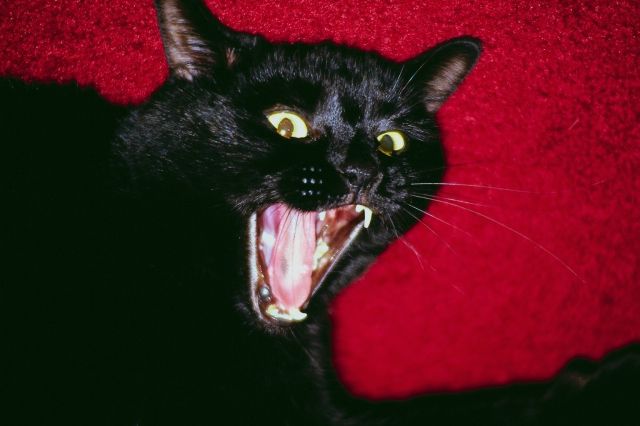

I also suggest that animals' ability to control their emotions - especially fear, anger and desire - (so-called "cortical over-ride") is a sign of consciousness on their part. Research in this area is still in its infancy.

Even if the majority of non-human animals lack phenomenal consciousness, they still matter. To claim that only beings with subjective states are ethically significant is a form of moral myopia. Most unconscious animals still have first-order desires that can be frustrated (Carruthers, 2004). Additionally, they, like other living things, have interests that can be harmed in measurable ways by stressful events.

Finally, I examine Midgley's argument that human beings and companion animals are emotionally symbiotic, and propose that the way in which ordinary people usually identify emotions in human beings is inseparable from the way they identify emotions in animals.

I discuss the alleged occurrence of "higher level" mental states in animals such as: language use; an awareness of oneself and the beliefs and desires of other individuals; abstract thought (e.g. the ability to categorise objects; the ability to form abstract concepts like "same" and "different", or numerical concepts; and the ability to follow rules); and an appreciation of the relationship between means and ends (as instantiated by tool use). Because these capacities have been used to argue that human beings possess a special status, I shall not follow a "bottom-up" approach and attempt to define these terms constructively by first examining their alleged occurrence different groups of organisms. Rather, I propose to adopt a "top-down" approach, in which these mental states will be defined using "paradigm cases" - that is, with reference to how they occur in human beings - before looking at alleged manifestations of these capacities in animals. The focus of my attention will not be the experimental research done on animals, but the philosophical interpretation of this research. I discuss the philosophical controversies surrounding the significance of these findings, before addressing the question of whether humans are different in kind or merely in degree from other animals, in their mental capacities.

I argue that the research into animals' higher-order mental states is still in its infancy, but we can be sure that some animals possess a kind of bona fide rationality regarding means and ends. Some animals also seem to be capable of genuine insight. New evidence suggests that a number of mammals (chimps, dogs and elephants) possess a rudimentary theory of mind. While the communication systems in some non-human animals are quite impressive, none of them can be called language.

Finally, I argue that moral agency is unique to human beings, as it presupposes a very high level of abstraction: in particular, a theory of mind, and an ability to form a concept of one's character and one's habits.