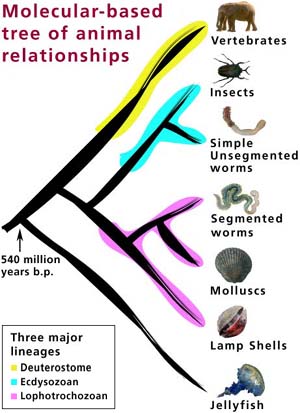

Bilaterally symmetrical animals fall into two groups: protostomes (which have one opening that serves as both a mouth and an anus) and deuterostomes (which have a mouth and an anus). Protostomes are by far the bigger group, and are made up of two sub-groups: ecdysozoans, or moulting animals, and lophotrocozoans.

The bodies of ecdysozoans are covered with an outer layer of light, thin, organic material (which some of them shed periodically) that functions as a skeleton. Unsegmented worms (e.g. nematode roundworms, such as C. elegans, and horsehair worms) and arthropods (insects, spiders and crustaceans) belong to this large group.

Most other phyla of worms, including segmented worms or annelids (e.g. earthworms) and flatworms (or platyhelminthes), as well as molluscs and lamp shells belong to the group known as the lophotrocozoans, a seemingly disparate clade of animals whose embryos develop in a similar fashion.

Only vertebrates, their close relatives and echinoderms are classified as deuterostomes.

This division is important for animal research. Apart from the vertebrates, all other deuterostomes have fairly simple nervous systems:

What this means is that we should not expect to find higher levels of cognition among the closest relatives of the vertebrates than among other animals. Our search for animal minds should not rely on mere genetic similarity to animals that are known to possess minds, but should examine the complexity of the nervous systems and behaviour of different phyla of animals.

It is interesting to note that the evolutionary line leading to the vertebrates (belonging to the phylum Chordata), probably diverged at a very early stage from that leading to invertebrate groups with more 'advanced' nervous systems (insects, cephalopods, etc.) - the common ancestor of all these bilaterians being of only flatworm grade. Of the deuterostomes, in fact, vertebrates are the only animals with highly developed nervous systems... (Prescott, 2001, p. 4, italics mine).