Is methodological naturalism a defining feature of science?

| Table of Contents | Part One | Part Two | Part Three | Part Four | Part Five | Part Six | Part Seven |

| Part Eight | Part Nine | Part Ten | Part Eleven | Part Twelve | Part Thirteen | Part Fourteen | Conclusion |

(Part Five in a series in response to Zack Kopplin.)

Highlights:

|

|

MAIN MENU A. What is Methodological Naturalism, and is it an essential part of the scientific method? B. Hume, Kant and the philosophical roots of Methodological Naturalism |

A. What is Methodological Naturalism, and is it an essential part of the scientific method?

In this mosaic, from a Roman villa in Sentinum, ca. 200 to 250 A.D., Aion, the god of eternity, is standing inside a celestial sphere decorated with zodiac signs, in between a green tree and a bare tree (summer and winter, respectively). Sitting in front of him is the mother-earth goddess of Nature, Tellus (the Roman counterpart of Gaia) with her four children, who possibly represent the four seasons. (Munich Glyptothek, Inv. W504.) Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

Looking through all the letters in support of your campaign, Zack, I've noticed a common theme: a desire to keep religion out of the science classroom. That's highly commendable. But where do you draw the line between science and religion? The criterion that's usually invoked today is that of methodological naturalism: science should confine itself to naturalistic explanations, and it should never invoke or appeal to the supernatural.

Four definitions of methodological naturalism

I'd like to begin by examining four definitions of methodological naturalism which I've encountered in the literature. I'll argue below that all of these definitions share a common flaw, which I shall attempt to remedy by putting forward an improved definition of my own, which not only explains what the term means, but why it is commonly regarded - mistakenly, in my view - as an essential part of scientific methodology.

The definition of methodological naturalism (MN) which I propose is a fairly robust one, and some proponents of MN might regard it as too strong, since (as I will argue below) adherents of a large number of religions hold contrary beliefs. I then contrast my definition of methodological naturalism with a weaker alternative version which contains a different rationale for why MN an essential part of scientific methodology. This version is based on arguments put forward by Professor Robert Pennock. I argue that this weaker definition of MN is untenable, as it would logically entail that more advanced intelligent life-forms than ourselves either don't exist anywhere in the cosmos (which violates the Copernican principle, beloved by anti-supernaturalists) or that these highly intelligent life-forms are in principle undetectable by us (which is absurd, as it would surely be easy for them to send us a signal encoding mathematical or scientific information which unambiguously confirmed their presence). Finally, I examine an even weaker version of MN, which bans references to supernatural agents in science, on the grounds that science has so far succeeded in explaining phenomena without having to invoke these agents. I argue that if this principle were allowed to stand, scientists would also have to ban, on methodological grounds, all references to any new or speculative scientific concept - which would mean that such concepts could never be tested and that science could never progress.

I conclude that my stronger definition of methodological naturalism is the only one that can stand, which means that if it is regarded as a vital part of scientific methodology, then people of many religious persuasions cannot be scientists.

I would now like to begin by examining some common definitions of methodological naturalism.

My first definition of methodological naturalism comes from Wikipedia, which provides a handy explanation of the term in its article on Naturalism (philosophy):

Methodological naturalism is concerned not with claims about what exists but with methods of learning what is nature. It is strictly the idea that all scientific endeavors — all hypotheses and events — are to be explained and tested by reference to natural causes and events. The genesis of nature, e.g., by an act of God, is not addressed.

My second definition is taken from Part One of an essay by Assistant Professor Peter S. Williams, entitled, Intelligent Designs on Science: A Surreply to Denis Alexander's Critique (2006). Williams' definition of "methodological naturalism" is essentially the same as Wikipedia's. Williams also provides a helpful explanation of the origin of the term:

Indeed, the phrase 'methodological naturalism' was apparently coined by theistic evolutionist Paul de Vries in a 1983 conference paper subsequently published as "Naturalism in the Natural Sciences," Christian Scholar's Review, 15 (1986), 388-396. De Vries distinguished between 'methodological naturalism', as a disciplinary method that is neutral concerning God's existence and 'metaphysical naturalism', which 'denies the existence of a transcendent God.' Hence De Vries states that the goal of the natural sciences is: 'to place events in the explanatory context of physical principles, laws, fields... the natural sciences are committed to the systematic analysis of matter and energy within the context of methodological naturalism.'[69] Methodological naturalism (MN) has thus been defined as the idea that: 'scientific method requires that one explain data by appealing to natural laws and natural processes.'[70]References

[69] Paul de Vries, 'Naturalism in the Natural Sciences,' Christian Scholar's Review, 15 (1986), 388-396.

[70] Garrett J. DeWeese & J.P. Moreland, Philosophy Made Slightly Less Difficult, (Downers Grove: IVP, 2005), p. 133.

My third definition of "methodological naturalism" is taken from is the locus classicus for the term: Paul de Vries' original 1983 essay, "Naturalism in the Natural Sciences." The following passage is especially pertinent:

I let go of my pencil and it immediately falls to the floor. Why? It would not be scientifically enlightening to say, "God made it that way." Similarly, scientists would not explain a particular rainstorm in terms of an Indian's rain dance or a farmer's prayers. Rainstorms are explained in terms of natural factors, such as air pressure and temperature — factors that themselves depend on other natural factors.In brief, explanations in the natural sciences are given in terms of contingent, non-personal factors within the creation. If I put two charged electrodes in water, the hydrogen and oxygen will begin to separate. If I were writing a lab report (even at a Christian College!), it would be unacceptable to write that God stepped in and made these elements separate. A "God Hypothesis" is both unnecessary and out of place within natural scientific explanations.

The naturalistic focus of the natural sciences is simply a matter of disciplinary method. It is certainly not that some scientists have discovered that God did not make phenomena occur the way they do. The original causes or ultimate sources of the patterns of nature are not proper concerns within any of the natural sciences — though they remain a wholesome and legitimate concern of many natural scientists. The natural sciences are limited by method to naturalistic foci. By method they must seek answers to their questions within nature, within the non-personal and contingent created order, and not anywhere else. Thus, the natural sciences are limited by what I call methodological naturalism. (p. 289)

For de Vries, then, the term "methodological naturalism" signifies an agreement, on the part of the scientific community, to confine its explanations of phenomena to those which invoke contingent, non-personal factors - and nothing else. Hence methodological naturalism necessarily excludes all appeals to miracles as scientific explanations of natural phenomena. De Vries takes pains to emphasize, however, that methodological naturalism does not prohibit scientists from appealing to God as an ultimate explanation of natural phenomena - provided that they make it clear that they are invoking God as a philosophical explanation rather than a scientific one.

My fourth and final definition of methodological naturalism comes from a widely-cited 2011 article by Professor Robert T. Pennock: "Can't philosophers tell the difference between science and religion?: Demarcation revisited" in Synthese 178(2), pp. 177-206, DOI: 10.1007/s11229-009-9547-3. Pennock's definition is succinct and to the point:

"MN [Methodological naturalism] holds that as a principle of research we should regard the universe to be a structured place that is ordered by uniform natural processes, and that scientists may not appeal to miracles or other supernatural intervention that breaks this presumed order. Science does not hold to MN dogmatically, because of reasons having to do with the nature of empirical evidence." (p. 184)

Intriguingly, Pennock seems to suggest in this passage that methodological naturalism is a revisable scientific principle - an interpretation he confirms later in his essay, when he writes that "MN [Methodological naturalism] is not dogma; it continues to be accepted in part because of its success - it works" (p. 199). He even hints that "if someone were to find a workable method of finding evidence for supernatural hypotheses" then scientists might consider "modifying the ground rule" of methodological naturalism (p. 199). However, he finds it "hard to even imagine what such an alternative method would look like" (p. 199), as "we have no experience and thus no knowledge of divine attributes" (p. 189). For these reasons, he contends that the Intelligent Design creationist's "call for a theistic science is ... unworkable" (p. 185).

What I'd like to argue is that none of the four definitions listed above constitutes an adequate formulation of the principle of methodological naturalism. A simple illustration will suffice to explain the flaw these definitions share. Suppose I were to define scientific methodology as follows: "the scientific method requires that one explain data by appealing to laws and processes beginning with the letter S." The reader would reasonably object that my definition was ad hoc, and that I had provided no justification whatsoever for my arbitrary exclusion of laws and processes beginning with letters other than S. In other words, a definition of scientific methodology which merely stipulates what kinds of explanations are to be called "scientific" is a very poor one. What we need is a definition of scientific methodology which authenticates itself: a definition which tells us not only what scientific methodology is, but why it works in that way and not some other way. In other words, what we need is a definition of scientific methodology which supplies its own epistemic warrant.

Let me be clear: I am not arguing here that defenders of methodological naturalism have failed to supply a rationale for their definition of scientific methodology. As we have seen, De Vries puts forward a highly persuasive rationale - which I shall critique below - in the paragraphs preceding his own definition, and Professor Pennock, in his 2011 essay, takes pains to lay out the scientific rationale for methodological maturalism. Rather, the point I wish to make is that the rationale for any good definition of scientific methodology should be contained within the definition itself, so that we need look no further when we ask ourselves why science has to work that way.

It needs to be borne in mind that methodological naturalism is a very powerful scientific claim. It has to be, in order to banish all talk of the supernatural from the domain of science - which is something that de Vries certainly wanted his definition to accomplish, since he insists that scientists "[b]y method ... must seek answers to their questions within nature, within the non-personal and contingent created order, and not anywhere else." If we are to banish God-talk from science, then we need to be very clear about why we are doing so.

What are the criteria for identifying things which are natural?

Before we can define methodological naturalism properly, we need to define the word "natural." How can we tell if something is natural or not? I would suggest that the following set of properties can be regarded as hallmark properties of natural entities:

(a) mutability, or the ability to undergo change;

(b) fixed dispositions, or uniform (i.e. regular) behavioral tendencies, which serve to characterize that object as a member of some natural kind, whose boundaries may be either sharp (e.g. the element oxygen) or fuzzy (e.g. a biological species such as the herring gull, Larus argentatus);

(c) interactive causation in space-time, or the ability to affect and be affected by the behavior of other natural objects, within some spatio-temporal domain;

(d) scientific laws describing all of the entity's behavioral dispositions, which are [ultimately] mathematical in form, and whose parameters are all capable of being quantitatively measured by some instrument; and finally,

(e) total contingency: for each and every one of an entity's attributes, scientists can meaningfully ask: "What makes it that way, and not some other way?"

On the definition of "natural" which I am employing here, the term "natural" means roughly the same as "physical." The term "empirical," on the other hand, is narrower in scope, as it only refers to things that we can observe, either directly (with our senses) or indirectly (using some instrument which then relays a signal to our senses). Thus any object within the observable universe is empirical, but objects in some other universe which is causally isolated from us are not empirical objects.

On my usage, the term "natural" may be legitimately contrasted not only with "supernatural", but with anything non-physical, whether it be God or a disembodied spirit. (Thus my definition of "natural" differs from the definition which a theologian would use. For a theologian, the last trait, contingency, would suffice to identify something as natural, as necessity is a hallmark trait of the Creator alone. The other four traits would not necessarily apply to spirits.)

The term natural, as I am using it, is not meant to be contrasted with "artificial", but with "spiritual". Thus an intelligent agent would qualify as natural if - and only if - it satisfies the definition given above.

What methodological naturalism is not - and what it is

I contend that methodological naturalism is a very strong methodological principle, which should not be confused with a number of weaker principles, for example:

(a) the principle that scientific questions are not to be resolved by appealing to the tenets of some revealed religion;

(b) the principle that science can be defined as the systematic study of physical phenomena, which are by definition part of Nature;

(c) the principle that science is limited to the study of regularly occurring phenomena - or alternatively, that science is limited to the study of replicable phenomena;

(d) the principle that scientists should look for natural explanations before invoking supernatural ones;

(e) the principle that scientists should avoid appealing to miracles, when attempting to account for physical phenomena; or even

(f) the principle that scientists should look for natural proximate causes when attempting to account for physical phenomena;

(g) the principle that scientists should confine themselves to natural causes, whether proximate or remote, when attempting to account for physical phenomena.

Many people might be inclined to identify methodological naturalism with principle (g), but I will argue below that they are mistaken: a more robust principle is required, in order for methodological naturalism to do the job it was intended to do.

If methodological naturalism is to banish all talk of the supernatural from the domain of science and establish science as an autonomous discipline in its own right, then it has to accomplish two objectives:

first, it has to maximize the scope of scientific explanations, in such a way as to bring all (and not just some or most) physical phenomena within the domain of science, so as to leave no room for phenomena which may require a supernatural explanation; and

second, it has to eliminate appeals to the supernatural, when attempting to explain observed phenomena.

Accomplishing the first objective is vital. For if there were a special category of unexplained physical phenomena which fell outside the domain of science, then the possibility that these phenomena required a supernatural explanation could not be ruled out. The existence of a category of unexplained (and possibly supernatural) phenomena would also threaten the autonomy of science, as there would be no way to prevent these phenomena from interfering with ordinary phenomena that scientists claimed to be able to explain.

The necessity of meeting the second objective should be obvious enough, for unless scientists can eliminate appeals to the supernatural when attempting to explain physical phenomena, methodological naturalism will never be successfully implemented, as a program for doing science.

None of the seven principles listed above accomplishes both of these objectives.

Principle (a): Scientists shouldn't resolve scientific questions by appealing to the tenets of revealed religions

Principle (a) says nothing about the scope of scientific explanations. In particular, it does not tell us whether science is able to explain all physical phenomena, or merely a large subset of those phenomena. Thus it fails to meet the first objective. Additionally, while it successfully eliminates appeals to the tenets of any religion when attempting to account for empirical phenomena, it nonetheless fails to eliminate appeals to the supernatural, when attempting to explain observed phenomena. For instance, principle (a) is perfectly compatible with natural theology: the quest to arrive at a knowledge of God based on observed facts and experience, apart from divine revelation. Such a God, if postulated as an ultimate explanation of physical phenomena, would be a supernatural Being. Thus principle (a) not only fails to meet the first objective, but it fails to satisfy the second as well.

Principle (b): Science is the study of physical phenomena which are found in Nature

Principle (b) also fails to satisfy either the first or the second objective. All it says is that the subject matter of science is physical phenomena, and only physical phenomena. However, nothing in this principle implies that science is competent to explain all physical phenomena. Moreover, the principle in no way implies that physical phenomena can be explained solely in terms of other physical phenomena. It could be the case, for instance, that while scientists can only study physical phenomena, they nevertheless have to invoke various non-physical phenomena - the proper study of which lies outside the domain of science - in order to fully account for the physical phenomena they observe in Nature. In other words, scientists might still be able to indirectly infer the existence of a non-physical (and possibly supernatural) realm, even though they are unable to study it directly. I therefore conclude that no self-professed supernaturalist has anything to fear from principle (b): methodologically, it is utterly innocuous.

Principle (c): Science is the study of regular phenomena (or alternatively, replicable phenomena)

Image of a large meteorite impact. Scientists hypothesize that the extinction of the dinosaurs and many other groups of organisms at the end of the Cretaceous period 65.5 million years ago was caused by one or more catastrophic events, including at least one asteroid impact (especially the one which created the Chicxulub crater) or possibly increased volcanic activity. Image courtesy of NASA and Wikipedia.

Likewise, principle (c) satisfies neither objective. It fails to meet the first objective, as it would severely narrow the scope of science, to exclude all singular events from its domain, thereby severely curtailing the scope of many of the historical sciences, which often have to deal with events which are not regular occurrences, or which are no longer replicable today. Not only would many "origin" events be excluded (e.g. the origin of the universe, or of life on Earth), but also one-off radiations of life occurring in the past (e.g. the Cambrian explosion) and more significantly, all catastrophic events, such as the Ice Ages or the K-T extinction event, caused by an asteroid impact, which killed off the dinosaurs and many other groups of organisms about 65.5 million years ago.

Aristotle and his medieval followers denied that singular anomalies resulting from chance and variability could belong to the subject matter of true science, since "there can be no demonstrative knowledge of the fortuitous." As a result, natural philosophy continued to restrict its investigations to common experience until the seventeenth century. (Aristotle, Posterior Analytics, 87b 19-20.)

In the modern era, the first scientist to mount a serious defense of principle (c) was Georges-Louis Leclerc, known as Comte de Buffon, who wrote in 1749 in his Theorie de la Terre that "The causes of rare, violent and sudden effects must not concern us, they are not part of the ordinary process of Nature" (quoted in Buffon: A life in natural history by Jacques Roger, Cornell University Press, 1997, p. 101). What Buffon wanted to do was to secure science's independence from theology, by excluding both miracles from the domain of science, but he did so at a very high cost: his methodological constraint forced him to exclude catastrophes from the scope of science as well. However, methodological naturalism is much more ambitious in its aims than Buffon's modest program for science; it endeavors to bring the entire range of observed phenomena under the domain of science. Because principle (c) deliberately narrows the scope of science, a modern-day methodological naturalist would therefore have no choice but to reject this principle.

What is more, principle (c) even fails to meet the second objective, of dispensing with appeals to the supernatural, since the only supernatural acts it would rule out are irregular ones - i.e. miracles. Moreover, one could argue that a miracle is not really an irregular occurrence, for as the nineteenth century mathematician Charles Babbage pointed out in his Ninth Bridgewater Treatise, even a singular value can be incorporated into the general description of a mathematical function. Babbage's point is readily grasped with the aid of a mathematical illustration. We can define a function y, as follows: y = 2x for x <> 100, y = 0 for x = 100. The apparently anomalous value of y when x = 100 is analogous to the occurrence of a miracle; it appears "irregular", but is in fact contained in the very definition of the function. Instead of calling it irregular, we should properly refer to it as discontinuous. The idea that God might have arranged in advance for miracles to occur at certain times in history when He created the world, by programming Nature at the outset to exhibit anomalous values for certain physical physical parameters at those times, might strike us as deeply distasteful, but Nature does not revolve around our aesthetic tastes.

Even if we were to generously grant that principle (c) precludes any appeals to miracles, a theistic proponent of principle (c) would be perfectly within his/her rights in attempting to explain natural phenomena by appealing to the supernatural but regular action of a Deity, Who maintains the world in existence and ensures that it behaves according to fixed laws.

In short: the reason why principle (c) fails to qualify as a genuinely naturalistic principle is that it only deals with the subject matter of science, which is defined as all regular or replicable natural phenomena. To rule out appeals to the supernatural, we need to limit not only the subject matter, but also the kinds of explanations that can be legitimately invoked in order to account for it. Rather than simply defining science as the study of regular or replicable phenomena, we should also say that the only explanations allowed in science are those which involve regular or replicable phenomena. Amended in this way, principle (c) does indeed rule out appeals to the supernatural, thereby satisfying the second objective. However, the claim is silent regarding whether all events occurring in the natural world (including one-off catastrophic events) can in fact be explained in scientific terms (by appealing to regular or replicable phenomena). Thus it still fails to meet the first objective.

Principle (d): Scientists should look for natural explanations before invoking supernatural ones

Principle (d) is merely a prudential maxim, which most supernaturalists would be quite happy to affirm. All it says is that we should look for natural explanations first, before invoking supernatural ones - which still leaves the door wide open to appeals to the supernatural, when all known natural explanations have been exhausted. Thus principle (d) fails to meet either the first objective listed above or the second: it does not tell us whether science will be able to explain all observed phenomena, and it fails to effectively exclude the supernatural from the domain of science.

Principle (e): Scientists should avoid appealing to miracles when accounting for physical phenomena

Principle (e) bars appeal to miracles by scientists, in the course of their work. But from a methodological naturalist perspective, principle (e) is still unsatisfactory, as it fails to meet either of the objectives listed above. Showing that a physical phenomenon is not miraculous does indeed entail that it is explicable in naturalistic terms, but that does not guarantee that it is explicable in purely naturalistic terms. For instance, scientific explanations at a proximate level might be entirely natural; but at the ultimate level of scientific explanation, a supernatural explanation might still be required. If we are to effectively banish the supernatural from the domain of science, then, we need a postulate which states that natural causes are sufficient to account for all observed phenomena. Thus principle (e) fails to satisfy the first objective stipulated above.

Second, principle (e) would mean that when faced with a mysterious phenomenon which totally confounds scientific explanations, scientists would still have the option of saying: "As a scientist I cannot explain that, but putting on my religious hat, I'd say we're witnessing a miracle here." (Think of the Lourdes Medical Bureau.) Thus principle (e) fails to meet the second objective as well.

I should add that if one also adopts principle (c), then principle (e) will be trivially true. Miracles are not required to invoke regularly occurring phenomena. Miracles are by definition extraordinary events; therefore they cannot be invoked to explain the ordinary. In Part D below, I will argue that medieval natural philosophers who upheld principle (e) did so only because they accepted principle (c): following Aristotle, they limited science to the study of regularly occurring natural changes. However, they also maintained that many events occurring in the world that appeared to be singular events (e.g. eclipses, earthquakes, epidemics) were in fact part of a regular pattern, and hence not miraculous. These philosophers did not reject miracles as such; rather, they wisely refrained from invoking them in order to explain what they believed to be regular events.

Principle (f): Scientists should look for natural proximate causes when attempting to account for physical phenomena

Detail of In hoc signo vinces (In this sign, conquer) by Raphael, Sala di Costantino, Vatican City. Image courtesy of NASA and Wikipedia. According to the historian Eusebius of Caesarea, Constantine I and his army had a vision of a chi rho on the sky, with the words "In this sign, conquer" in Greek emblazoned below it, just before the Battle of Milvian Bridge against Maxentius on 28 October 312 - a battle that Constantine went on to win, making him undisputed ruler of the Roman Empire. During the Middle Ages, this event was commonly accepted as a bona fide miracle. As such, it would have been regarded as a singular celestial phenomenon: the kind of event which falls outside the domain of science, according to medieval natural philosophers. Although they would have recognized this event as a miracle, these philosophers nevertheless adopted a very matter-of-fact attitude towards comets and eclipses, to which they assigned natural proximate causes, because they regarded them as regular events.

Principle (f) is also deficient from a methodological naturalist perspective, as it does not tell us whether science is able to explain the entire gamut of observed phenomena - which is the operating assumption that methodological naturalism needs to make, in order to satisfy the first objective listed above.

It is interesting to note that principle (f) would be robbed of its force if it were combined with principle (c), which stipulates that science should confine itself to the investigation of regular phenomena. All it would entail then is that regular phenomena have a natural proximate cause - a trivial point on which naturalists and supernaturalists alike would readily agree. As we shall see, this was precisely the view upheld by medieval natural philosophers in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, who wrote about celestial phenomena such as comets and eclipses. In their view, these phenomena were not singular but regular occurrences with a natural cause, and people who believed otherwise were credulous simpletons.

At the same time, however, these same philosophers would have acknowledged the miraculous nature of singular celestial phenomena of a portentous nature, which could not possibly be explained as regular events - for example, the cross in the sky with the words, "In this sign, conquer" emblazoned above it, that was allegedly witnessed by the Emperor Constantine and his entire army shortly before the Battle of Milvian Bridge in 312 A.D. - an event which was universally accepted in medieval Christian Europe as a miraculous act of supernatural intervention. My point here is that the natural philosophers of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries who appealed to principles (c) and (f) in their scientific writings were not methodological naturalists, but rather, highly disciplined supernaturalists. Their use of principle (f) did not prevent them from invoking the supernatural miracles to explain celestial portents which could not be "regularized."

But the most serious problem with principle (f) is that it also fails to satisfy the second objective. It does not eliminate appeals to the supernatural, when attempting to explain physical phenomena; all it does is make the supernatural a remote rather than immediate explanation. Principle (f) is entirely compatible with the practice of looking for natural proximate causes for physical phenomena, while still invoking God as a First Cause - which is precisely what natural philosophers in the Middle Ages did.

Principle (g): Scientists should invoke only natural causes when attempting to account for physical phenomena

Many people (including, it seems, Paul de Vries) would equate methodological naturalism with principle (g). However, principle (g), like principle (f), says nothing regarding the competence of science to explain the entire gamut of natural phenomena - which is the operating assumption that methodological naturalism needs to make, in order to satisfy the first objective listed above. It does not tell scientists what they are to do when faced with phenomena which appear recalcitrant to a naturalistic explanation.

Additionally, principle (g) fails to satisfy the second objective. It does not eliminate appeals to the supernatural, when attempting to explain observed phenomena; all it eliminates is scientific appeals to the supernatural. A supernaturalist could consistently uphold principle (g), but at the same time maintain that observed phenomena also require a deeper, metaphysical explanation which goes beyond the phenomena themselves, to some underlying non-physical Cause.

At this point, a methodological naturalist might respond: "That's the whole point of the definition. Whether physical phenomena ultimately require a supernatural explanation is a question that science cannot answer, one way or the other. If it did, then methodological naturalism would collapse into metaphysical naturalism. So long as the supernaturalist you described above keeps God out of science, he/she is still a bona fide methodological naturalist."

What this response overlooks, however, is that the the raison d'etre of methodological naturalism is to protect the autonomy of science, as an intellectual mode of inquiry. Science's autonomy is guaranteed only if its explanations of observed phenomena are fully adequate. But if the empirical phenomena which science deals with cannot be fully explained within a scientific framework, but also require a theistic metaphysical framework in order to fully explain them, then the domain of science can no longer be isolated from that of theology, and science is no longer self-contained as a mode of inquiry.

A consistent methodological naturalist, then, must be committed to holding that science is capable of fully explaining phenomena as such. This does not mean, however, that methodological naturalism must collapse into metaphysical naturalism. The reason is that science says nothing about the inner reality, or being, of things. In Kantian terms, science does not deal with noumena, or things in themselves; rather, it deals with phenomena, or appearances. It is these phenomena which a consistent methodological naturalist must allow that science is fully capable of accounting for, without the need for any underlying metaphysical explanations. For instance, an Argument from Motion to the existence an Unmoved Mover (Aquinas' First Way) would fall foul of methodological naturalism, as I am construing it here, since motion (or change) is a natural phenomenon; whereas an Argument from Contingency to the existence of a Necessary Being (Aquinas' Third Way) would not, since being belongs in the realm of noumena.

It should be apparent by now that methodological naturalism goes much further than claims (a), (b), (c), (d), (e), (f) and (g). What it says can best be expressed by the following principle:

(h) When doing science, we should assume that natural causes are sufficient to account for all physical phenomena, and that for precisely this reason, all talk of the supernatural is banished from science.

Or as Professor Lawrence Lerner memorably put it in a short piece entitled, Methodological Naturalism vs Ontological or Philosophical Naturalism, which was excerpted from a longer article he published for the NCSE (February 14, 2003), entitled, Proposed West Virginia Science Standards: Evaluated by Lawrence Lerner, Attacked by Intelligent Design Creationists:

Methodological naturalism is not a "doctrine" but an essential aspect of the methodology of science, the study of the natural universe. If one believes that natural laws and theories based on them will not suffice to solve the problems attacked by scientists - that supernatural and thus nonscientific principles must be invoked from time to time - then one cannot have the confidence in scientific methodology that is prerequisite to doing science. The spectacular successes over four centuries of science based on methodological naturalism cannot be gainsaid.

It needs to be borne in mind that methodological naturalism (MN) is a methodological principle, not a metaphysical one. For instance, methodological naturalism does not assert that miracles never occur in the natural world - although anyone who accepted principle (h) could not consistently countenance them. Nor does methodological naturalism claim that the laws of Nature are never broken - although it would instantly be rendered invalid if they were. Finally, methodological naturalism does not assert that the natural world is all there is, or that nothing exists outside Nature, or that there are no supernatural beings. All of these statements are metaphysical claims, whereas the claim made by MN is a methodological one.

The robust version of methodological naturalism proposed here secures the autonomy of science, but at a price. It clashes with a key claim made about the world made by many of the world's leading religions - namely, that miracles have occurred on rare occasions in the past. Most Christians believe this (the Resurrection is an obvious example). Likewise, many Jews believe that the nature miracles recorded in the Tanakh [or what Christians call the Old Testament] actually occurred - for instance, the prophet Elisha's raising a dead boy to life in 2 Kings 4:29-37. Muslims also believe that God worked miracles in the past - e.g. through Noah (see Sura 11 and Sura 23). Belief in miracles is common among Hindus, and even Buddhism has its miracles. If you believe that miracles have occurred at any time in the past, then you cannot believe that natural causes are sufficient to account for all physical phenomena - and thus you cannot accept principle (h), which declares that they are. Thus if principle (h) is fundamental to science, then if you believe in miracles, you cannot practice science. This requirement would exclude the majority of the world's religious believers, some of whom were Nobel Prize winners, as we've seen. So much for the claim that methodological naturalism is religiously neutral.

Nor do the problems stop there. Textbook definitions of methodological naturalism [MN] usually emphasize that MN sidesteps questions relating to ultimate origins. As Paul de Vries puts it in his 1983 essay, "Naturalism in the Natural Sciences": "The original causes or ultimate sources of the patterns of nature are not proper concerns within any of the natural sciences." But if the epistemic definition of MN in principle (h) is the only definition which adequately grounds MN in a consistent manner, then the question of ultimate origins cannot be bracketed in this fashion. To be a consistent methodological naturalist, you must believe that science is fully capable of explaining physical phenomena - which means that you have to believe that science is capable of accounting for their origin as well. The majority of the world's religious believers, however, would hold that the world was created at some point in the past by God or some other supernatural Deity, without Whom the world would never have come into existence. If you accept principle (h), then you will have to abandon this belief as well.

By now, we are left only with religious believers who either accept that the world is eternal, or who hold that the laws of Nature explain how the cosmos could have popped into existence, without any need for a Creator. What's more, these religious believers must also hold that the Deity has never broken the laws of Nature, and that nothing exists within the natural world which science cannot fully account for. Only religious believers who accept all of these things can be methodological naturalists, on the epistemic definition of MN which I am proposing, in principle (h).

Thus I would maintain that a fully consistent version of methodological naturalism, while not overtly hostile to religion as such, has anti-religious implications, in that it would preclude a very large proportion of the world's religious adherents from practicing science.

Methodological naturalism Mark II: Is Professor Pennock's weaker version of methodological naturalism viable?

At this point, some "accommodationist" defenders of methodological naturalism might object that the definition I have proposed above is too strong. They may wish to put forward a weaker version of MN - let's call it methodological naturalism Mark II - which would make it true by default, on the grounds that scientists have no way of testing for supernatural causes, and have managed to account for physical phenomena perfectly well without positing them:

(i) Scientists need to test their hypotheses, and because (1) there is no way in principle of testing for supernatural causes, and (2) scientists have hitherto managed to fully explain physical phenomena purely in terms of natural causes, all talk of the supernatural is banished from science.

This version of methodological naturalism sits well with the arguments of Professor Robert T. Pennock, in his 2011 article, "Can't philosophers tell the difference between science and religion?: Demarcation revisited" (Synthese 178(2), 177-206, DOI: 10.1007/s11229-009-9547-3), where he writes:

"My own account has been to explicate scientific naturalism as a methodological commitment, not an a priori metaphysical one, and to rationally reconstruct it as arising from a basic value in science, namely to the idea of testability or more precisely, to science's epistemic value commitment to the authority of empirical evidence. MN [Methodological naturalism] is not dogma; it continues to be accepted in part because of its success - it works. Moreover, we do not necessarily rule out modifying the ground rule if someone were to find a workable method of finding evidence for supernatural hypotheses. On my analysis of the relevant concepts I find it hard to even imagine what such an alternative method would look like and I have seen no proposal that comes close to being conceptually coherent (certainly IDCs [intelligent design creationists] do not have such a method) but I remain open to being show wrong." (p. 199)"Would it even be intelligible to speak of supernatural "weight" or supernatural "color"? If these were truly meant to be different from the notions of weight and color as we understand these concepts in terms of our ordinary natural experience, then we have no ground upon which to draw any inference about them. Supernatural "design" is of a kind. As Hume pointed out, we have no experience and thus no knowledge of divine attributes. Those who think otherwise, whether in the service of proving or disproving the divine, invariably do so by illegitimately assuming naturalized notions of the key terms or other naturalized background assumptions." (p. 189)

However, I would argue that this weaker version of methodological naturalism is fatally flawed. I base my argument on Arthur C. Clarke's Third Law, which states that any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic. One corollary of this law is that any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from the activities of a supernatural Being. In other words, if a smart enough race of aliens were to visit us, they could perform amazing feats that would fool us into thinking they were gods.

Personally, I am inclined to think that Arthur C. Clarke's Third Law is wrong. I don't think any race of aliens could resurrect a corpse, for instance, and even if they attempted to fool us into thinking they'd done so by somehow making the corpse disappear and instantly replacing it with another body teleported from somewhere else, I think our scientists could probably devise a way to detect the switch. But let that pass. My point here is that Pennock is committed to upholding Arthur C. Clarke's Third Law. If he denies it, then he has to acknowledge that there is a way to distinguish the activities of a supernatural agent from those of natural agents - and that would destroy his whole case for excluding all talk of the supernatural from science - namely, that scientists have no way in principle of testing for supernatural agents.

But if there is no way to distinguish supernatural agents from advanced aliens, then the Pennockian principle (i) put forward above will have to be modified, as follows:

(j) Scientists need to test their hypotheses, and because (1) there is no way in principle of testing for the existence of very advanced intelligent beings (whether natural or supernatural), and (2) scientists have hitherto managed to fully explain physical phenomena without positing these beings, all talk of the activities of very advanced intelligent beings (whether natural or supernatural) is banished from science.

It should be clear that principle (j) is indefensible as a rule of scientific methodology. First, it violates the hallowed Copernican principle, beloved of anti-supernaturalists, which states that there is nothing special about our Earth and its place in the universe. This means that if intelligent life evolved on Earth, then we should expect it to have evolved on other Earth-like planets too. But some of these planets are billions of years older than our own, which means that by now, the intelligent life-forms on these planets would be light years ahead of us, in terms of their technology. If this is the case, then principle (j) is wrong, as it denies the legitimacy of even talking about such beings, on methodological grounds. Thus if Pennock wishes to uphold (j), he will have to abandon the Copernican principle.

Second, the claim in principle (j) that scientists have no way in principle of testing for the existence of very advanced intelligent beings is clearly false, as it would be easy for them to send us a signal which unambiguously confirmed their presence: the first 1,000 digits of pi, for instance. (The odds of 1,000 successive digits encoding the first 1,000 digits of pi by chance is 10^1,000, which is greater than the number of events, or operations, that have occurred in the history of the entire observable universe from the Big Bang up to the present - a number estimated by Seth Lloyd at 10^120 in his article, Computational capacity of the universe in Physical Review Letters 88:237901, 2002.) Scientists receiving a mathematical signal of this sort would automatically infer that it came from an advanced civilization. If the civilization then sent us further signals containing scientific information that was hitherto unknown to us, then scientists would know they were much more advanced than we are.

Since principle (j) contains a demonstrably claim, and since principle (j) is entailed by principle (i), it follows that principle (i), which I shall refer to as the Pennockian version of methodological naturalism, must be a flawed methodological principle.

Paul de Vries to the rescue?

Perhaps we can shed more light on the justification for methodological naturalism by re-examining Paul de Vries' original 1983 essay on "Naturalism in the Natural Sciences," which I cited above. Here is what de Vries writes about supernatural explanations (all citations below are taken from page 289 of de Vries' article):

I let go of my pencil and it immediately falls to the floor. Why? It would not be scientifically enlightening to say, "God made it that way." Similarly, scientists would not explain a particular rainstorm in terms of an Indian's rain dance or a farmer's prayers. Rainstorms are explained in terms of natural factors, such as air pressure and temperature — factors that themselves depend on other natural factors.

In this passage, de Vries rejects supernatural explanations as "not ... scientifically enlightening." However, the same objection could be made to the claim that a physical phenomenon - say, a monolith on the Moon - was produced by some unknown race of aliens who were far more technologically advanced than we are. Since the latter claim is generally acknowledged to be scientifically meaningful at least, there can be no a priori grounds for excluding the former.

But let us go along with de Vries' logic, for the sake of argument. Assuming he is right, what has he actually demonstrated? So far, all he has established is principle (f), which states that scientists should look for natural proximate causes when attempting to account for physical phenomena. We are still a long way from principle (g), which stipulates that scientists should confine themselves to natural causes, whether proximate or remote, when attempting to account for physical phenomena.

De Vries continues:

In brief, explanations in the natural sciences are given in terms of contingent, non-personal factors within the creation. If I put two charged electrodes in water, the hydrogen and oxygen will begin to separate. If I were writing a lab report (even at a Christian College!), it would be unacceptable to write that God stepped in and made these elements separate. A "God Hypothesis" is both unnecessary and out of place within natural scientific explanations.

Two points are pertinent here. First, de Vries fails to explain why a good scientific explanation has to be not only contingent but also impersonal. If there are other intelligent life-forms in outer space, then there must be some physical phenomena (i.e. alien artifacts) for which the proper scientific explanation is a personal one, appealing to the intentions of their makers. It would be puzzling if de Vries rejected such an explanation as unscientific.

Second, de Vries' rejection of the explanation that "God stepped in and made these elements separate" commits him to nothing more than principle (e), which states that scientists should avoid appealing to miracles, when attempting to account for physical phenomena, or alternatively, principle (f), which states that scientists should look for natural proximate causes when attempting to account for physical phenomena. It would preclude scientists appealing to God as an immediate cause of physical phenomena, but not as an ultimate cause. We are still nowhere near establishing principle (g).

But de Vries is not finished yet. He continues:

The naturalistic focus of the natural sciences is simply a matter of disciplinary method. It is certainly not that some scientists have discovered that God did not make phenomena occur the way they do. The original causes or ultimate sources of the patterns of nature are not proper concerns within any of the natural sciences — though they remain a wholesome and legitimate concern of many natural scientists. The natural sciences are limited by method to naturalistic foci. By method they must seek answers to their questions within nature, within the non-personal and contingent created order, and not anywhere else. Thus, the natural sciences are limited by what I call methodological naturalism.

In this paragraph, de Vries finally espouses principle (g), when he insists that "[t]he original causes or ultimate sources of the patterns of nature are not proper concerns within any of the natural sciences." He simply asserts this; he does not tell us why. However, since the complete explanation of any phenomenon requires tracing it back to its ultimate cause, then it seems that de Vries is committed to the claim that science does not aim to give complete explanations of phenomena. But if scientific explanations of phenomena may (for all we know) be incomplete, then the autonomy of science as a discipline can no longer be guaranteed, since we cannot exclude the possibility that the Creator and Ultimate Cause of natural phenomena might decide to alter their regular patterns of behavior at some date in the future, for reasons best known to Himself. On de Vries' proposed account of science, any variation in the regular patterns of nature would throw the whole of science into disarray.

The argument I have put forward here is that by excluding questions about ultimate explanations from the domain of science, de Vries has thrown into jeopardy the autonomy of science as a discipline - which was the very thing he wanted to uphold. We are forced to conclude, then, that de Vries' justification of methodological naturalism is insufficient, because it fails to preserve the autonomy of science from the domain of the supernatural.

Methodological naturalism Mark III: Will an even weaker version of methodological naturalism do the trick?

At this point, the reader may be wondering whether a defender of methodological naturalism might be better off dropping Pennock's testability criterion and relying solely on the success of science in explaining phenomena over the past 400 years, without invoking supernatural beings. In other words, perhaps we should define methodological naturalism as follows:

(k) Because scientists have hitherto managed to fully explain physical phenomena purely in terms of natural causes and without positing supernatural agents, all talk of the supernatural is banished from science.

I would like to point out that principle (k) is a very weak version of methodological naturalism, as it suggests that scientists would abandon the principle instantly, if they discovered a natural phenomenon that proved recalcitrant to naturalistic explanations.

The deficiencies in principle (k) should be readily apparent. Substitute any speculative scientific notion (e.g. magnetic monopoles) in place of "supernatural agents" and the flaw in the principle becomes obvious:

(l) Because scientists have hitherto managed to fully explain physical phenomena purely in terms of natural causes and without positing magnetic monopoles, all talk of magnetic monopoles is banished from science.

There are two obvious problems with such a principle. First, it's a non sequitur: the practical conclusion simply does not follow from the factual premise. Just because scientists have succeeded so far in explaining phenomena within the cosmos without resorting to entities such as monopoles (the existence of which has been hypothesized by some physicists), it does not follow that they shouldn't even talk about them.

Second, principle (l) (and any other principle like it) is far too dogmatic, as it would rule all new, unproven scientific concepts out of court on the sole grounds that scientists have never had to invoke them in the past, when they knew less than they do now. If principle (l) and others like it were taken seriously, science could never progress, as scientists could never even talk about, let alone test, new scientific concepts.

Since the weaker, Pennockian version of methodological naturalism in principle (i), which is based on the notion of testability, entails a demonstrably false principle (j), and since the even weaker principle (k), based on the success of science, fares even worse, I conclude that the only viable version of methodological naturalism is the strong version, formulated in principle (h) above - a version which, as we saw, runs afoul of the claims of many religions.

What's wrong with methodological naturalism, in a nutshell

It might still be objected that while I have refuted various versions of methodological naturalism, I have not yet provided any positive grounds for abandoning it. That is a fair criticism, which I would now like to remedy by putting forward the following syllogism.

1. One of the aims of science is to discover fully adequate explanations of physical phenomena.

2. For at least some physical phenomena, the only fully adequate explanation is one which appeals to intelligent agency. [Artifacts are an obvious example.] Any explanation of these phenomena which did not appeal to intelligent agency would be inadequate.

3. Scientists cannot know whether an explanation of a physical phenomenon is fully adequate unless they can ascertain whether the phenomenon in question is capable of being completely explained without invoking the notion of intelligent agency. (If the answer is negative, then any purported explanation of that phenomenon which ignores the notion of intelligent agency will be incomplete.)

4. There is no reason in principle why the universe - or the multiverse, for that matter - should be capable of being fully explained without invoking intelligent agency.

5. If the multiverse requires an explanation in terms of intelligent agency, then by definition, the Intelligent Agent Who explains the multiverse is supernatural.

6. By refusing to even consider the possibility that the multiverse may have a supernatural explanation, scientists are failing to properly carry out their scientific work, which is to look for fully adequate explanations of physical phenomena.

7. Hence, in order for scientists to do their work properly, science should remain methodologically open to the (epistemic) possibility that a supernatural Being exists, and that the postulation of this Being is required in order to fully explain physical phenomena.

The critical premises here are the first, second, fourth and fifth.

Premise 1: Is the explanation of physical phenomena one of the aims of science?

Someone who adopts Pierre Duhem's approach to science will find the first premise problematic. Duhem famously rejected the view that the aim of science was to explain physical phenomena, arguing that because explanations involve appeals to metaphysical concepts, and because scientist A and scientist B may have radically different views on matters relating to metaphysics, it would be impossible to ever secure agreement among scientists that a given explanation of phenomena was in fact the right one. Other alternatives would always suggest themselves. The sheer diversity of possible interpretations of quantum mechanics may appear to lend a certain plausibility to Duhem's argument.

In response, I would argue that:

(i) different explanations of physical phenomena have testable consequences, which means that it should be possible to eventually rule out some metaphysical concepts, if they entail conclusions which are at variance with the data;

(ii) the fact that there is such a variety of interpretations of quantum mechanics tells us nothing more than that the science is in its infancy;

(iii) as Alvin Plantinga points out in his essay, Methodological Naturalism?, a radical rejection of all metaphysical concepts would make belief in an external world and an objective past unscientific, which would mean that belief in common descent would be unscientific. If we defined science in this narrow fashion, it would mean that an evolutionist could not be a methodological naturalist!

Another question that might be asked is whether the first premise commits me to the view that science aims to discover the true explanations for physical phenomena. Some scientists contend that science should not be reagrded as the search for true explanations of phenomena, but rather, as the search for useful explanations that generate testable predictions which are fully in accord with the observed facts. As it happens, I support the former view, but the argument I am propounding here is neutral between the two views. All that matters for my purposes is my claim in premise (2), that for some physical phenomena (e.g. artifacts), scientific explanations which appeal to the notion of intelligent agency can explain facts about those phenomena which alternative explanations cannot.

Premise 2: Is the notion of intelligent agency indispensable for the scientific explanation of some physical phenomena?

Most people (including most scientists) would regard premise (2) as undeniably true. Forensics and archaeology are two obvious examples of scientific disciplines where the notion of intelligent agency comes into play. Indeed, premise (2) can only be denied by reductionists, who hold that explanations appealing to intelligent agency can always be replaced by lower-level explanations in which intelligent agency does not figure, or by eliminative materialists, who maintain that there are no such things as intentional acts, which means that all explanations which appeal to the beliefs, desires and intentions of intelligent agents are fundamentally misguided.

The point I wish to make here is that reductionism and eliminative materialism are both strong metaphysical positions. They are much stronger, for instance, than the more modest (and more widely held) version of materialism known as emergentist materialism, which readily grants that the beliefs, desires and intentions of intelligent agents are irreducible to underlying physical processes, but nevertheless insists that our mental acts supervene upon these physical processes. For an emergentist materialist, higher-level explanations of physical phenomena which appeal to the notion of intelligent agency are a legitimate part of the scientific endeavor, which cannot be replaced by lower-level explanations.

Thus someone who wishes to challenge my argument against methodological naturalism by rejecting premise (2) has to adopt a very radical metaphysical position, as well as committing him/herself to the odd view that all scientific explanations of physical phenomena which appeal to the notion of intelligent agency are ultimately dispensable. But the whole point of scientists adopting methodological naturalism, as opposed to metaphysical naturalism, is that it allows them to avoid committing themselves to controversial metaphysical positions. In other words, if a methodological naturalist were to question premise (2), he/she would be in effect acknowledging that to be a methodological naturalist, you have to be a metaphysical naturalist too, which defeats the whole purpose of methodological naturalism.

Premise 4: Is there any reason in principle why the multiverse should not require intelligent agency to explain it?

Premise (4) is a premise which could only be denied by a metaphysical naturalist who believed that the whole concept of a supernatural agent is absurd. The same comments apply here as for premise (2): if a methodological naturalist were to deny this premise, then he/she would be acknowledging that in order to be a methodological naturalist, one must be a metaphysical naturalist as well: a self-defeating position.

Premise 5: Does an Intelligent Agent who explains the multiverse need to be supernatural?

That leaves us with the fifth premise. Someone might query this premise, arguing that perhaps that which explains the multiverse is something outside Nature as we know it, but still governed by scientific laws of its own. We might call it "Nature 2," as opposed to our own multiverse (of which our universe is a tiny part), which is "Nature 1." If some intelligent agent who lives inside Nature 2 is capable of generating the laws and occurrences found in Nature 1, then we have no need to invoke a supernatural agent in order to explain the multiverse, after all.

The problem with this proposal is that if Nature 2 explains Nature 1, then it must somehow contain Nature 1 - and if it contains Nature 1, then the laws of Nature 1 are subsumed by the (more general) laws of Nature 2. (This is true regardless of whether the laws of Nature 1 are generated by a blind process occurring in Nature 2, or by an intelligent agent within Nature 2, who created Nature 1 as a simulation.) However, the term "multiverse", as I am using it here, simply refers to the largest domain of entities whose behavior is regulated by scientific laws. Hence if Nature 2 has laws of its own, Nature 1 is not the multiverse; Nature 2 is.

It follows that any intelligent agent who explains the multiverse (as I am using the term) is a Being Who is not bound by any laws at all. An intelligent agent who is not bound by laws can only be described as supernatural.

The conclusion I have argued for here is that there are strong prima facie grounds for regarding science as an open-ended enterprise which has no built-in methodological constraints on its search for fully adequate explanations of physical phenomena. In other words, there is no principled reason why science cannot take us to God, if by "God" we mean an infinitely wise Being.

The shifting grounds of support for methodological naturalism

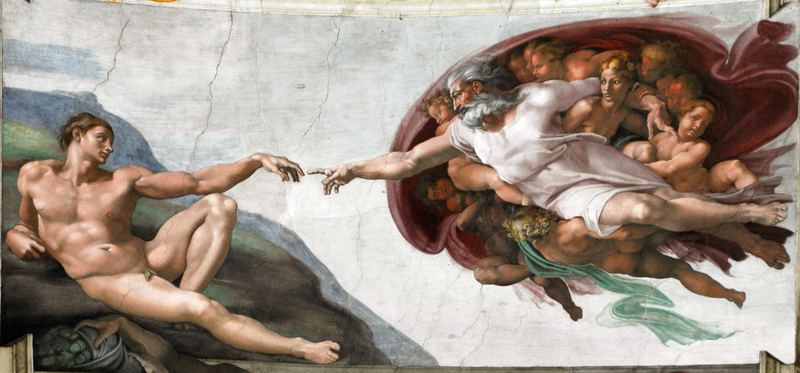

The Creation of Adam, by Michelangelo. Sistine Chapel. 1510. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

1. Supernaturalism in science would open the door to an infinite menagerie of supernatural beings

One facetious reason which is commonly given for keeping all talk of the supernatural out of science is that if we open the door to supernatural agents, there are an infinite number of possible candidates: a Deistic God who never tinkers with Nature; the God of classical theism, who is perfectly capable of doing so; the God of the Bible, who frequently does so; the God of Islam, who reveals Himself but disdains miracles; or for that matter, Krishna, Mazda, Zeus, Odin or even the Flying Spaghetti Monster. In reply, it might be urged that corporeal deities are, by definition, part of the physical order and hence not supernatural, but that still leaves us with a bewildering (and potentially infinite) variety of incorporeal candidates whose essential characteristics might differ, and whose attitudes and intentions may be diametrically opposed to one another. In which God should we trust?

The short answer to this question is: that shouldn't concern us too much. Even if scientists were able (at some future date) to conclusively establish that certain phenomena were caused by a supernatural Agent, but were utterly unable to say which one, that would still be an interesting scientific finding in its own right, which would be of immense significance for the human race - just as it would have been if the face on Mars had proved to be the work of some unknown extra-terrestrial intelligence.

The longer and more thoughtful answer is that the number of natural explanations for a newly observed phenomenon is also potentially infinite, and there is no way of testing all of them; nevertheless, scientists usually have little difficulty in practice in settling on a "best candidate" or a small, finite range of competing candidates. If scientists are able to eliminate a potentially infinite number of bad or defective natural explanations for a phenomenon, is there any good reason why they couldn't also eliminate a vast swath of second-rate supernatural explanations, on the methodological grounds that they were either too ad hoc or too vague? That would at least narrow the field.

Finally, there appears to be no reason in principle why scientists couldn't eventually arrive at a consensus on some of the essential characteristics of a supernatural Creator. For instance, the discovery of a structure in Nature that turned out to be capable of storing an indefinitely large (i.e. potentially infinite) amount of information would seem to indicate that its Creator had an (actually) infinite capacity to store and/or access information. (Only something with an actually infinite capacity is capable of generating something with a potentially infinite capacity.) One fruitful question for scientists to examine would be whether in fact the human brain (or for that matter, the brains of mammals and birds, who are probably conscious) has a potentially infinite capacity for storing information, or whether it has a built-in upper limit.

2. A supernatural being could wreak havoc with the cosmos, making it impossible for scientists to do their work

A second frequently heard objection to allowing supernaturalism in science is that a supernatural Deity, if it existed, would be capricious: such a Being could violate the laws of Nature at a moment's notice, without giving any warning, making it impossible for scientists to go about their everyday business. Now, for all scientists know, the law of gravity may fail to hold in five minutes' time. Epistemically, we cannot rule out this possibility, but on a practical level, we still conduct our lives in the assurance that the laws of Nature which have reliably held in the past will continue to hold in the future. However, if scientists became aware of some Being that was capable of interfering with the laws of Nature, which they rely on in their everyday work, they would be forced to entertain the real (as opposed to hypothetical) possibility that their experiments might or might not work. The continual distraction generated by the existence of a supernatural Agent would make it impossible, in practice, for scientists to go about their work. If we want scientists to concentrate on their research and avoid having to deal with metaphysical issues beyond their ken, then supernatural agents have to be excluded from the scientific worldview, as a matter of practical necessity.

I have to say that I find this objection disingenuous, as it glides over different senses of "capable." For instance, would a God who (as the nineteenth century mathematician and theologian Baden Powell envisaged) is by nature incapable of breaking his promises, and whose laws of Nature have the status of edicts (i.e. promises which even God cannot break), make it impossible for scientists to do their work? Obviously not. Researchers would have no problem with such a scientifically benign Deity. What about a God who promised not to violate the laws of Nature, except for the gravest of reasons, and only in ways that caused no harm to human life, and that left laboratory research intact? My guess is that scientists would rapidly adjust to this situation: after all, there's very little practical difference between an experiment that's known to work 99.999999% of the time and one that works 100% of the time. What about a supernatural Being Who is silent, and says nothing at all about His intentions? This situation would be a little disquieting at first, but in the end, scientists (like the rest of us) would have to learn to live with it. If enough time passed without any nasty "incidents", then scientists would eventually conclude that the Being in question posed no threat to science, and go back to their research.

3. Supernaturalism is a science-stopper

A third objection to allowing supernaturalism in science is that it is a science-stopper. Michael Ruse makes this argument in a recent article for The Guardian (5 May 2010) entitled, Intelligent design is an oxymoron, where he wrote:

...[A]lthough ID is not bad science – it is not science at all – its intent is deeply corrosive of real science. As Thomas Kuhn pointed out repeatedly, when scientists cannot find solutions, they don't blame the world. They blame themselves. You don't give up in the face of disappointments. You try again. Imagine if Watson and Crick had thrown in the towel when their first model of the DNA molecule proved fallacious. The very essence of ID is admitting defeat and invoking inexplicable miracles. The bacterial flagellum is complex. Turn to God! The blood clotting cascade is long and involved. Turn to God! That is simply not the way to do science.

What I find most astonishing about Ruse's argument here is that it was fully answered by someone whom he quoted in his article: William Whewell (1794-1866), who in his 1833 work, Astronomy and general physics. Considered with reference to natural theology (New York, Bairper and Brothers, 1856), turned the tables on his atheistic opponents by charging them with being science-stoppers for failing to ask why the universe existed:

It is related of Epicurus that when a boy, reading with his preceptor these verses of Hesiod, thus translated: "Eldest of beings, Chaos first arose, Thence Earth wide stretched, steadfast seat of all The Immortals," the young scholar first betrayed his inquisitive genius by asking "And chaos whence?" When in his riper years he had persuaded himself that this question was sufficiently answered by saying that chaos arose from the concourse of atoms, it is strange that the same inquisitive spirit did not again suggest the question "and atoms whence?" And it is clear that however often the question "whence?" had been answered, it would still start up as at first. Nor could it suffice as an answer to say, that earth, chaos, atoms, were portions of a series of changes which went back to eternity. The preceptor of Epicurus informed him, that to be satisfied on the subject of his inquiry, he must have recourse to the philosophers. If the young speculator had been told that chaos (if chaos indeed preceded the present order) was produced,by an Eternal Being, in whom resided purpose and will, he would have received a suggestion which, duly matured by subsequent contemplation, might have led him to a philosophy far more satisfactory than the material scheme can ever be to one who looks, either abroad into the universe, or within into his own bosom. (1833, pp. 133-134)

In Whewell's view, the real "science-stopper" is not supernaturalism but the premature introduction of final causes into science: once we know why something exists, there is a temptation to stop asking further questions about it. Hence he insists that scientists should endeavor to identify the physical causes of natural phenomena, tracing them as far back as they can possibly go, before inferring the existence of a Creator of the natural world. Then and only then are scientists in a position which allows them to see the end or purpose of the natural phenomena that they are investigating:

Final causes are to be excluded from physical inquiry; that is, we are not to assume that we know the objects of the Creator's design, and put this asssumed purpose in the place of a physical cause. We are not to think it a sufficient account of the clouds that they are for watering the earth, (to take Bacon's examples,) or "that the solidness of the earth is for the station and mansion of living creatures." The physical philosopher has it for his business to trace clouds to the laws of evaporation and condensation; to determine the magnitude and mode of action of the forces of cohesion and crystallization by which the materials of the earth are made solid and firm. This he does, making no use of the notion of final causes: and it is precisely because he has thus established his theories independently of any assumption of an end, that the end, when after all, it returns upon him and cannot be evaded, becomes an irresistible evidence of an intelligent legislator. He finds that the effects, of which the use is obvious, are produced by most simple and comprehensive laws; and when he has obtained this view, he is struck by the beauty of the means, by the refined and skilful manner in which the useful effects are brought about; — points different from those to which his researches were directed. (1833, p. 219)

In an essay entitled, , philosopher Paul Herrick puts forward a principle of inquiry which he calls the Daring Inquiry Principle (DIP):

When confronted with the existence of some unexplained phenomenon X, it is reasonable to seek an explanation for X if we can coherently conceive of a state of affairs in which it would not be the case that X exists.

This is an open-ended principle of inquiry, unlike the one he attributes to atheist philosopher Keith Parsons, and which he humorously dubs the Principle of Parsony:

In general, the nonexistence of X is no mystery unless, given general background knowledge, its existence is either expected or is no more unexpected than what does exist (i.e., its existence is at least as expected as that which does exist).

The Principle of Parsony tends to make people incurious about "brute facts". For instance, Professor Parsons concludes that we have no rational basis for expecting that some other universe might have existed instead of ours, or that there might have been nothing at all, just as we have no basis for expecting that the moon might have been made of green cheese. The existence of an ex-hypothesi eternal universe, therefore, is no more of a mystery than the nonexistence of a moon made of green cheese.

In a post of mine, entitled, Why the moon isn’t made of green cheese (Part One of a reply to Professor Keith Parsons) I argued that there was in fact a reasonable answer to the question, "Why isn't the moon made of green cheese?", which even a young child can understand:

So, how would I answer a young child's question: "Why isn't the moon made of green cheese?" If the child was about five years old, I'd answer it like this. To make cheese, you need milk. The only way you can make milk naturally is from animals like cows, who feed their babies with it. There are no animals on the moon, and there never have been. Animals need air, and the moon doesn’t have any, because it's too small to keep its air. So there's no way of naturally making a moon out of cheese, let alone green cheese. The key notion being deployed here is that certain raw materials (e.g. milk, from which cheese is made) have a characteristic natural origin: they originate in this way, and no other.If the child was aged eight years or older, I would add that scientists believed that all of the matter in the universe was originally a very light gas called hydrogen, and that over the course of time, other heavier elements formed, such as iron. Carbon (found in the proteins contained in cheese) formed too, but it was just one of many elements. So even if cheese could form naturally from the elements, without the need for animals, it would be very unlikely that the moon would contain nothing but cheese – a bit like flipping a million coins and getting nothing but heads. At this level, the answer to the child's question, "Why isn't the moon made of green cheese?" invokes a rudimentary notion of probability.

If the child were ten years or older, I would further add that the most popular scientific theory of the moon's origin is that it was formed from the debris left over when another planet collided with Earth. To encourage the child to keep an open mind, I would also mention that some scientists are proposing a new theory of the moon’s formation, according to which a massive nuclear explosion occurred at the edge of Earth’s core, flinging red-hot, liquid rock into space. The orbiting debris gradually coalesced into what is now our moon. No matter which theory is correct, however, the logic is the same: since the Earth isn’t made of green cheese, we wouldn’t expect the moon to be. So the answer to the child’s question in this case depends on the added piece of information that the Earth materially contributed to the moon’s formation.

two arguments put forward by Herrick, showing why the Principle of Parsony is a very poor explanatory principle, because it’s a science-stopper.

First, the Principle of Parsony would rule out a lot of questions that most scientists would consider perfectly reasonable to ask. Here’s one example proposed by Professor Herrick: