— Marcia Pablo (Salish/Kootenai NW Montana)In the field of ethnography, for too long we have watched the extraction of our traditional knowledge

from our elders - knowledge used not to benefit our people but to launch a professional career or create

a "professional expert" on our tribal lifeways. These careers have been built on the shoulders of our elders,

the true Ph.Ds of our culture.

For the Nation there is an unrequited account of sin and injustice

that sooner or later will call for national retribution.

— George Catlin

UPDATES:

September 29, 1999 | October 12, 2000 (colonialism) | July 25, 2001 (American holocaust)

January 5, 2002 (grave desecration) | July 5, 2002 (Yanomami genocide)

January 4, 2004 (An Answer to Johnson and Haley) | May 20, 2004 (Ishi)

June 13, 2004 (No Brave Champion) | June 21, 2004 (No Brave Champion - cont'd)

June 26, 2004 (Thanks Clay Singer) | July 20, 2004 (Chinigchinich) | August 11, 2004 (Art and Science)

February 23, 2005 (Rock Art and Science) | June 6, 2005 (Australia) | July 16, 2005 (Who Stole Indian Studies?)

October 11, 2005 (Vine Deloria, Jr. on Anthropology) | March 9, 2006 (Archaeology Answerable)

April 14, 2006 (Postscript: the two Custers) | January 26, 2007 (Minik) | April 7, 2007 (Chumash "risk minimization")

Ethics and Archaeology (April 12, 2008) | Negative Capability (summer solstice 2009)

Secrets of the Tribe (November 9, 2011)

On January 25, 1992, Chumash clan members met at the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History to discuss the misuse of mission genealogies that led to misrepresentations they believe have harmed their people. Attending the meeting were museum director Dennis Power, Leslie Power, anthropologists Steve Craig and John Johnson, archaeologist Clay Singer and Phil Holmes of the Park Service. Among the Chumash present were: Kote Lota (who invited me to the meeting), his wife A-lul’Koy and John Ruiz of the Owl clan; Sal Perez, Redstar and Mati Waiya of the Turtle clan; Charlie Cooke of the Eagle clan; Pilulaw Khus of the Northern Bear clan; Choy Slo of the Blackbird clan; Lydia Rodriguez, Anwai Wilanci (Shoshone) and Alan White Bear, chairman of the Coastal Band of the Chumash Nation. Some drove many miles from San Luis Obispo, Santa Ynez, Santa Paula and Thousand Oaks to attend the meeting. At issue was a reluctance by certain anthroplogists to regard the Chumash as Chumash, an attitude based on research in mission archives that the Chumash regard as insulting. Along with the insistence of some that this is none of the museum’s business, it was pointed out that mission records only offer a fragment of the whole picture, at times quite inaccurate, and that only they, the Chumash, know these intricate family ties in full – information they regard as totally private.

The Spaniards responsible for the mission records totally ignored clan organizations. Mixed residency at mission San Fernando, mission San Gabriel and Fort Tejon makes the existing records, based most often on the mother’s name, misleading at best. There was anger expressed at the meeting over insinuations that they are not Chumash based on this faulty data, and all desired to establish equally as good relations with the museum as they have with the Park Service. It was agreed that there was a need for the scientists to broaden their understanding of the meaning of ”Chumash”.

Many complaints have been leveled at John Johnson over this issue, the latest being one that led to this meeting stemming from a conversation he had with Phil Holmes. Steve Craig said that the museum should recruit and not exclude people from the community, which happens when one person of Chumash origin not acknowledged by the others as representing them is regarded by the museum as the representative of the Chumash. Kote Lota, creator of the Shalawa Meadow Medicine Circle, calls such a person a ”pet Indian” and felt that such preferential treatment excludes the rest of the Chumash community. The anthropologist in question he saw as a ”nuisance”. Speaking directly to John Johnson, Kote said, ”You are hurting a lot of people – a lot of families.”

John Ruiz, Kote’s half-brother, was irritated at how relations with the museum had deteriorated since the death of Travis Hudson and the tomol (plank canoe) project a few years ago, when the participants were denoted as ”Chumash” when it suited the museum’s publicity needs. But now they are humiliated by on-going insinuations from the museum that they are not Chumash. All present were very upset over this.

Clay Singer pointed out how early anthropology made an attempt to classify the world’s races into white, red, black, etc., and how this was grounded in scientific ignorance. This becomes a key issue in view of legal questions concerning the repatriation of native artifacts and skeletal remains in museums to their original cultures. Posing the question, ”Are there pure-blooded English, Germans or anything else?”, Clay answered that there is no such thing as a pure-blooded anything, for the nature of human society is to ”bleed and breed” over national boundaries.

Charlie Cooke spoke of his thirty-three years of struggles to be recognized as who he is, and stated, ”We are the most likely descendants to receive the artifacts, regardless of what tribes may represent our ancestry.” Addressing this point, Clay Singer said that legally, even a full-blooded Norwegian, if accepted into the tribal group as a bonafide member, is entitled to all the benefits the law provides the group. Genetically determining who is and who is not Chumash is a futile snipe hunt, a chimera that can never be caught. As for another misconception, someone exclaimed: ”We don’t like being called Indians. Indians are in India.”

The grievances that culminated on this day have been building up for years, with other unforgotten incidents in the past as their source. Among these was an LA Times article based on an interview with John Johnson in which ethnographic information was misused. A-lul’Koy said that it was degrading to have strangers scrutinizing one’s family and making decisions about private matters that only her people are qualified to make. She stated that things her "auntie” told her about her family tree contradict the mission records. John Johnson examined the mission records for her family as well as those for her husband Kote’s family. Earlier, he told the present writer that Kote was not Chumash and things Kote said about his ancestry should be ”taken with a grain of salt.” This is a roundabout way to call a man a liar, and Kote is understandably offended.

No one brought up the point that it was, at the very outset, gestures of ill-will towards the Chumash that resulted in these coveted mission records, an insult by the Spanish colonizers to an entire culture. (At San Juan Capistrano mission, the Spanish priest Boscana referred to the Acjachemen people as ”monkies”.) A-lul’Koy added that her people live to protect the land, its sacred sites and the burial grounds which have already been desecrated. She did not want her grandchildren to have to fight the museum to be recognized.

Redstar, who recently released two tame condors in the back country of Ventura county, regretted that the oldest of the elders have not ”come out” because of this official attitude towards the Chumash community, which fosters fear and apathy. One old Saticoy aunt of his used to prepare ceremonial herbs, but no longer. Redstar said that this traditional knowledge is needed today. He showed all present his infant daughter, who is genetically part of both cultures, and lamented that she and her children might still have to continue the tedious struggle for recognition.

John Ruiz indignantly asked: ”Why do we have to prove to you who we are?” and Steve Craig admitted that it was ”a tremendous invasion of privacy” to delve into old records and draw conclusions about living people and their families. Choy Slo believed that John Johnson ”acted in a malicious manner towards our nation.” Museum director Dennis Power acknowledged there was room for improvement.

The misunderstandings come from the written word – the inflexible written word. Clay Singer pointed out the gap between the two cultures present at the meeting, the one used to written records and the other to the oral tradition. Scientists usually believe written records to be the more accurate of the two, but Pilulaw claimed the oral tradition was the more accurate. Perhaps Pilulaw was alluding to the unending stream of falsehoods recorded in print generation after generation in the occident.

Speaking in defence of his besieged colleague, Steve Craig said that until Chumash artifacts and human remains at the museum are repatriated to the Chumash, it is the role of the museum staff to protect the interests of the anthropologists as well as the artifacts. He blamed zealous land-developers and journalists for eliciting information from John Johnson and then misusing it, and believed that John Johnson needed to be ”protected”. Kote Lota then asked if John Johnson was that terribly naive. Kote complained of christian ”pet Indians” who have little knowledge of traditional Chumash values stepping into the limelight and speaking on behalf of people who do not acknowledge their authority to do so. Mati Waiya added: ”**** does not represent us,” referring to a person of Chumash descent who had collaborated with John Johnson.

Finally, the main purpose of the meeting was on the table. However unwillingly, John Johnson offered an apology to the Chumash present, as he apologized years ago for a damaging LA Times article that hurt many people. (The museum’s official minutes of this meeting do not mention this apology.) The general feeling was that it was hoped a third apology will never be needed. Johnson was thanked ironically for having united all the Chumash clans in a way that they have been seldom united. Normally, the Chumash community keeps a low profile, and even anthropologists know little of their activities. But, as Mati Waiya put it, once burial grounds are desecrated or other offences committed, they emerge in defence of their homeland with a very determined sense of purpose. They asked the museum to have a better idea of what is happening in the Chumash community at large, to have more empathy with real, living human beings, and not mere scientific concern for a culture officially deemed extinct.

Clay Singer suggested that a cultural anthropologist could act as liaison between the Chumash community and the museum, thought by all to be a good idea. When asked by Kote if he would like to be this liaison, Clay politely declined. Choy Slo was most often silent, but when he chose to speak, his voice reverberated authoritatively with thousands of years of Chumash culture. He wished to emphasize the gravity of this issue, gravity which has consistently been ignored by American society and anthropologists studying them. Should the offences continue, and this grave situation be regarded in a nonchalant manner, Choy Slo spoke of ”other levels of war.” As quiet testimony to the gravity of his words, Alan White Bear, war chief of all the clans, stood in the back with his arms folded, listening to every word. Choy Slo added: ”We are the keepers of the Western Gate,” a reference to Point Conception, one of the most sacred sites in the Chumash realm.

Kote Lota has told me that Humqaq (Point Conception) is not only sacred to the Chumash, but to tribes all over California, and even to the Shinnecock of Long Island on the Atlantic coast. On a visit a few years ago, Kote exchanged ceremonial gifts with a Shinnecock elder. The Shinnecock are the keepers of the Eastern Gate: Montauk Point. (On my way out to Montauk Point in 1972 on a camping trip, I was arrested and sent to jail in East Hampton for disobeying a ”No Trespassing” sign posted on the beach.)

Choy Slo summed up by saying that the balance tips in favor of thousands of years of habitation of this land, as opposed to less than two short centuries of American presence in California. Looking at the museum spokesmen, Choy Slo said: ”You work for us.”

The meeting was coming to an end. Some had very long drives back home and had to leave earlier than the rest. Kote Lota commented that by the end of the day, all Chumash in all counties would know what had happened at the meeting – that is how fast news spreads. One of the last people to speak was Lydia Rodriguez, a close relative of **** . She was brief, saying only that **** does not speak for the entire family, adding: ”She hurt me by what she had to say,” and then left the room in tears.

Copyright © Theo Radic´ 1999

What John Anderson refers to as the ”California holocaust” presents a painful dilemma for all who choose to know their homeland in depth and confront it. For Native Californians, it is a subject of anger and ongoing suspicion of the American Dream. For Euro-Americans it can only be an issue of shame. Most refuse to shoulder this shame, feeling the painful burden too much to endure. And so, they choose to be proud instead. Gregg Castro, from the Salinian people near Salinas, has written that it is very difficult for most Americans to undergo what he calls a ”grief ritual”. For Euro-Americans, this involves a bitter confrontation with the atrocities and genocides of our history hiding behind the flattering lies and patriotic pride that we were force-fed in school.

This ritual is usually full of emotion and pain. It is obviously very disturbing to some people. I think the reason Native Americans do this is to see if there is any empathy. This is not usually a planned, conscious act. Through this ritual, Native Americans can measure the reverence and respect that others have for one’s heritage.Among those Americans who find this ”grief ritual” difficult or impossible to undergo, are included even anthropologists and archaeologists who ”study” native cultures. One such culture studied by the anthropologists was the Yahi (now extinct). For unexplainable reasons, Ishi, the last Yahi, was not allowed a final sacred rest by the anthropologists - even in death. Does it matter that this ghoulishness excuses itself because it is carried out "in the name of science"? At his death in 1916, Ishi's brain was removed and sent to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC. The scientific information thus obtained (whatever that may have been) was regarded as more important than the most rudimentary respect granted the dead all over the world. Anthropologist Orin Starn's research eventually led him to the Smithsonian's Natural History Museum where he beheld Ishi's brain: "Ishi's brain was right there in Tank 6 of the Wet Collection [...] There were thirty-two other brains floating in the stainless steel tank, each in a cheesecloth sack tied with a plastic accession tag. [...] At the same time, I knew it was much more than happenstance that Ishi's brain had ended up in the Smithsonian. Alfred Kroeber had sent the brain there knowing that Alex Hrdlika was amassing brains for scientific study." (American Indian Quarterly Summer/Fall 2005) It took almost one hundred years for Ishi's remains to be released by the scientists for a proper burial by Native Californians. This criminal betrayal of a friend is perhaps the greatest shame Alfred Kroeber's memory shall have to bear. This is the trangsgression for which anthropology is answerable.Gregg Castro, ”Educating Ourselves About Archaeology”, News from Native California, Summer 1996

[Note: In the occident reverence for the dead is not always a given fact. The irreverent treatment given Ishi’s remains evokes many similar cases in our culture, a long tradition of intellectual necrophilia, whether for reasons of dissection, religious mummification or sheer perverse curiosity. Perverse curiosity led to Mozart’s presumed skull, dug up 10 years after his burial, being handled as a curio by many people for over 200 years after his death, to this very day. Mozart’s skull changed owners several times as a bauble that was bought and sold. (Beethoven, Liszt, Schubert and Haydn all suffered the same indignity, their skulls stolen by students of phrenology and displayed by collectors.) After a century of such irreverent commerce, Mozart’s skull was put on display at the Mozart Museum in the city of his birth, Salzburg. It was on public display for 50 years, but today it is housed at the museum out of public view. Despite the fact that few if any people brought such glory to Austria as did Mozart, his memory is defiled by this academic necrophilia. It is like the supposed bones of Buddha that led to the founding of temples to house these relics, in total opposition to the Master’s teachings. After nearly 100 years, the American scientists came to their senses and allowed Ishi’s remains to be properly buried. 213 years after his death, Mozart has yet to be shown this respect in Austria.]

The above article has been included on this site in view of certain scholars who provide arguments helping to remove the sacred status from sacred domains for purposes of development. Much academic knowledge and pseudo-knowledge is being used to help pave the way for the commercialization of California’s last untouched natural beauty by sabotaging legitimate aboriginal claims in the legal process. This collaboration is unforgivable. To preserve this beauty is a sacred calling for all who love it, regardless of ethnic background.

Update, October 12, 2000:

COLONIALISM

"Anthropology answerable" is also an issue dealt with in Current Anthropology (April 1999) by Les W. Field, in which he deems "anthropology complicit with colonialism", and "anthropologists...as formal instruments of the bureaucratic machinery". He begins his article thus: "California's statehood and assimilation into the United States during the 19th century were accompanied by genocide against the indigenous population; among those peoples that survived, a large number were officially eraced by a federal policy of nonrecognition in which anthropologists and anthropological knowledge played a role." Although Field is also an anthropologist, he expresses "outrage" over "anthropology's role in... historical injustices" that created unacknowledged tribes and disenfranchised Native Americans all over the country. He believes that anthropologists can help rectify these injustices. Bringing them to light may induce certain scholars to understand the harm they have caused, however unknowingly. By officially declaring the Ohlone of the San Francisco Bay Area and other living tribes "extinct", Alfred Kroeber as well was guilty of this academic complicity against the indigenous peoples of our state.

"The ethnography of Native America is a field dominated by male Euro-American scholars who rarely ask or care what the people they study have to say about their work. The fact that thousands of years of oral history preceded their work carries little weight in a society in which only written records comprise history. Even when considering the written records, the scholars often display historical amnesia in avoiding the wealth of documents that reveal the genocidal crimes of Manifest Destiny. They would like to believe that the mindless brutality (not only of soldiers and pioneers, but of science itself) is safely concealed in the past. American history reveals the exploitation of Native resources like timber and minerals without anything being given back to the Native American communities from which they were taken.In a similar manner, non-native scholars of Native America have extracted the resources of oral literature and history, profiting on them by attaining money and fame, often without returning anything to the Native American communities from which they were taken. We share the continent with them, and yet our own literature cannot attain the depth of saturation in its bedrock as that of Native America. Their ancient tradition of poetry is closer to the idea of the "Delphic oracle" issuing from the womb of the Earth herself, than much of the written poetry of our civilization.” (excerpt from The Whetting Stone)

One need not be an anthropologist to be knowledgable about indigenous American cultures and histories. The so-called ”objective observer” from the scientific community who in no way wishes to mix his own feelings with the native people he ”studies”, just may not see the forest for the trees. This thoroughly scientific approach led Alfred Kroeber and others to apply Freudian prejudices to the Yurok that could even include such deep insights as their being ”paranoid”, ”anal retentive”, or suffering from other psychoanalytical ailments.

The accompanying coldness and impudence of such scientific methods (that have offended many native people) may just mean that the best observers of these cultures have been non-anthropologists. For example, the historian Francesca Fryer’s in-depth trilogy, SANDSPIT, dealing with the Yurok and their interaction with white society, provides a more rounded, human, view of this culture than Kroeber’s. Not being an ”objective observer,” Ms. Fryer dares to mix her own life and feelings with her subject matter, and in doing so provides the reader with an emanation of living people absent from most anthropological texts. It just may be that culture is not at all something conducive to minute, a priori scientific study, but to random encounters and unexpected revelations that are part of the artistic process.

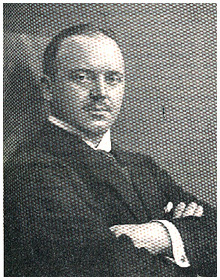

The artistic method of observing Native American cultures was used with astounding results by George Catlin, before there even was such a thing as anthropology. Franz Boas is generally considered the "father of anthropology" in North America. When I once suggested to an archaeologist in Santa Barbara that George Catlin in fact deserves this title, even though he was a mere artist, I was given an academic look that said: "Here is an ignorant fellow." I persist in my belief. The reasons for this belief can be read on my George Catlin page.

Assuming full responsibility for these genocides is the most forbidden of all taboos in my country today, which, as everyone knows, has always acted on the side of ”good”. Some scholars have compared ”Manifest Destiny” with Hitler’s Lebensraumpolitik, and have revealed the horrifying similarities between these two ”master races”. They tell us that Hitler is known to have expressed admiration for the efficiency of the American genocide campaigns agains the First Nations, viewing it as a forerunner for his own plans for mass-extermination of the Jews.* Hitler’s plan was to conquer the world. Manifest Destiny was a plan to conquer the West. However, as one conquers one’s way westward, circumnavigation of the globe is the natural result of Manifest Destiny. Today, ”globalization,” ”global economy” and ”global culture” are all the end result of the destructive vision: Manifest Destiny. That is, Manifest Destiny is a dream about conquering the world, the same dream as that of Adolf Hitler – "the wholesale moral bankruptcy of the entire western world."(Lilian Friedberg)

(excerpt from Hitch-Hiker in Hades)

__________________________________

*”Dare to Compare: Americanizing the Holocaust,” Lilian Friedberg, paraphrasing Hitler’s biographer John Toland, American Indian Quarterly, Summer 2000. vol. 2 no. 3. Note: Ms Friedberg is both of Jewish and Native American origin.

The desecration of First Nation graves has occupied archaeologists and physical anthropologists for two centuries. Rumaging in the available archives, researchers are stumbling upon horror stories that make one cringe with shame as a citizen of this nation. The perpetrators are not only enraged Civil War generals, "injun killers" or scalp-hunting psychopaths, but highly respected men within the hierarchy of science. In the last half of the 19th century, the United States Surgeon General ordered that the heads of slain aboriginal warriors on the battlefield were to be rountinely severed and sent back to the Smithsonian Institution for scientific study. These heads, along with a vast number of skulls plundered from First Nation cemeteries, were compared with European skulls to prove the popular 19th-century theory "polygenism," in which First Nation peoples were scientifically declared "inferior" – evolved even from a different branch of evolution than the ethnologists studying them. The scientific demand for these aboriginal skulls was so great that a veritable mining operation was begun to meet the demands of phrenolgists, who purchased thousands of skulls to build "cranial libraries", leaving a wake of calamitous sorrow and desperation in the native villages thus defiled.

This contempt for the sanctity of the First Nations was normal policy for the government and the ethnologists whom they employed. For example, Alaska’s Konaig people have been (in vain) seeking justice from the Smithsonian Institution for over one hundred years. They request that over eight hundred of their ancestors brutally dug up from a village cemetery in 1900 be returned to them for proper reburial. The perpetrator of this crime was not a night-marauding necrophiliac, but none other than Alex Hrdlicka, esteemed founder of the Smithsonian Institution’s "division of physical anthropology". Before the very eyes of the horrified Konaig villagers, and with rigorous scientific exactitude, the ethnologist and his team dug up one grave after the other, shipping the eight hundred cadavers back to the nation’s capital where they remain to this day.

This official contempt for the First Nations went on to infect the ranks of 20th-century ethnographers. An old photograph from the beginning of the century reveals archaeologists Earl Morris and Jesse Walter Fewkes after a season of "field work". They stand like proud hunters behind baskets and boxes filled with human remains plundered from native cemeteries. In the foreground a row of skulls are lined up on the ground. One thinks of the terrible images from Cambodia’s "killing fields", remains of a ghastly genocidal crime for which the criminals are sought today by an international tribunal. The Pawnee writer James Riding In, a professor at Arizona State University, condemns what he calls "orgies of grave-robbing" that have disturbed the eternal rest of the Indigenous Peoples, rest that all peoples of the world desire for their dead. He sees these trespasses committed in the name of science as a "spiritual holocaust."

Such grim deeds have left terrible wounds among the indigenous people that remain unhealed even today. And the offenses continue, one hundred years after Hrdlicka’s crimes. In – not the 1890s – but the 1990s, unforgiveable outrages were routinely committed against the last aboriginal peoples of South America. In this the last decade of the millennium, the naturalist and adventurer Charles Brewer visited the Yanomami people, living a once-peaceful stone-age existence in the jungle between Venezuela and Brazil. Having been fashionable subjects for ethnologists already in the 1960s, the Yanomami were already scarred by contact with western science. Thirty years later, Brewer "bought" much Yanomami land for a big scale mining operation. During a few years, he had five thousand mine-workers flown in and out of the region, leaving behind them epidemics, alcohol, weapons and prostitution. In his book, Darkness in El Dorado , Patrick Tierney estimates that fifteen hundred Yanomami died as a result of the mining operation. This same author, who also lived among the Yanomami, writes of an apprentice of Claude Lévi-Strauss, Jacques Lizot, who established a private harem of native boys deep in the jungle where he was conducting "field work". (Perhaps this ghastly sexual aberration is deemed acceptable by the perpetrators because Plato himself was a practitioner.)

But the worst villain of Tierney’s very controversial book is the cultural anthropologist Napoleon Chagnon, who arrived among the the Yanomami in 1964. Like the 19th-century ethnologists, Chagnon replaced honest scientifc methods with a preconceived idea of the inferiority of the Yanomami in relation to the Europeans. According to Patrick Tierney, Chagnon wrote of the Yanomami as a violent and aggressive people – "the fierce people". The book given this title became a best seller, and spread the author’s appraisal of a what he claimed to be a brutal, grim and treacherous people. When Patrick Tierney visited them twenty-five years after Chagnon, he was surprised to find a shy and hospitable people that did not fit his predecessor’s vicious portrait.

On the contrary, the brutal, grim and treacherous peoples – as most of us know by now – left Europe and populated the Americas by tyrannical force. Tierney writes that violence arrived among the Yanomami with Chagnon, who brought weapons and indiscriminately handed out gifts to some, denied them to others, thus causing internal strife. Worst of everything – a revelation that has made Tierney an outcast among established ethnologists – is Chagnon’s nonchalance in giving measles vaccinations. The vaccine contains a small amount of the measles virus which is effective in civilization. But the jungle people had different metabolisms, and instead around one hundred Yanomami became infected with measles and died. When Chagnon’s helicopter landed near an extremely remote jungle village, the village was destroyed in the machine’s winds and injured a number of Yanomami, some of whom had to be rescued from beneath fallen roofing and poles. The headman’s wife had such a pole rammed through her leg. The medicine men began ritual chants against an evil visitation from civilization. Chagnon went home to bathe in his fame, while leaving unanswered this vital question: what good reasons do anthropologists have to enter remote jungles and use these societies as their personal laboratories, doing them no good whatsoever?

By his [Chagnon’s] own account, the wars that made the Yanomami famous

began on the day he arrived in the field, November 14, 1964; also by his own

account, their worst epidemic started the day he returned after a long absence,

on January 22, 1968.

Patrick Tierney, Darkness in El Dorado

The science of anthropology – the study of mankind – has systematically avoided the most fundamental axiom of this study: know thyself. The proverbial "objective observer" of science does not, after all, observe himself. (Freud’s attempt at this poetic task is questionable.) This glaring error in methodology has led to much human suffering inflicted by anthropologists, just as the above quote by Patrick Tierney reveals the "collective agony" of the Yanomami of the Venezuelan jungles. Had Napoleon Chagnon and his colleagues devoted time to the axiom "know thyself," they would not have been pleased with the result, as we others are not pleased. For the Yanomami people, it would have been best if this anthropologist had never been born. They detested him, as is evident in the palm-frond effigy of Chagnon made by the Yanomami after his departure, which they shot full of arrows.

Seemingly harmless anthropological practices like establishing genealogies can cause great turmoil, as happened with the Chumash in California (see top of page), and with the Yanomami in Venezuela. The most taboo subject among the latter was to pronounce the names of the dead outloud. This is exactly what the anthropologist Chagnon forced them to do while making detailed genealogies of Yanomami ancestors. Chagnon was a professor at the University of California at Santa Barbara, in Chumash territory, where other anthropologists caused turmoil and rivalries among the Chumash by also making genealogies based on the taboo names of the dead.

The Yanomami could not understand the interest of this complete stranger in the names of their dead, unless it was for purposes of black magic and witchcraft. To name the dead among them was a grave insult, a cause for divisions and wars. This was precisely the result of the anthropologist Chagnon’s research in Yanomamiland, as Tierney coroborates: "Within three months of Chagnon’s sole arrival on the scene, three different wars broke out, all between groups who had been at peace for some time and all of whom wanted a claim on Chagnon’s steel goods." So covetous were they of steel machetes and axes, that tribesmen would trade their daughters for a blunt machete or axe. Inter-tribal accusations of black magic, all Chagnon’s doing, led to bloody wars among the Yanomami that did not exist among "the fierce people" (as Chagnon called them) before the arrival of the anthropologists.

Even worse, the measles vaccinations with the very dangerous Edmonston B virus, administered by Chagnon and others, left hundreds, maybe thousands dead, according to Tierney: "At that time [1968], over three thousand Yanomami lived on the Ocamo headwaters; today there are fewer than two hundred." The evidence Tierney gathered points to one thing: the measles vaccine itself caused the devastating measles epidemic. "The scientists kept moving on and the epidemic moved on with them." The main purpose of the vaccinations was a clinical study on this isolated people who were used like white mice in acquiring scientific statistics – all for the personal advancement of the scientists. Most contemptible of all in this genocide was Chagnon’s supervisor in the measles vaccinations, the geneticist James Neel from the University of Michigan’s Department of Human Genetics.

Far from benefiting from Chagnon’s visits, the Yanomami culture, as Tierney states over and over again, was devastated. Although directly responsible for the deaths of thousands of human beings, his crimes go unpunished, when they indeed come down to mass murder of unequaled proportions. Chagnon became famous and prosperous at their expense. The Yanomami were the losers. Such is very often the case with the intrusion of anthropologists into peaceful tribal domains. Tierney’s investigation reveals crimes similar to nazi and Japanese medical experiments on living human beings during World War II. These crimes against humanity were knowingly committed under the guise of innoculating the Yanomami against measles, when in truth they were part of an experiment involving racial theories as aberrant as those of the nazis.

Although the geneticist James Neel was largely responsible for these crimes (which he deviously tried to cover up) the whole evil scientific project among the Yanomami fits perfectly into the frame of anthropology. As Tierney writes, the word anthro has become a part of Yanomami vocabulary, and is not a term of endearment. Although the Greek term means "man" or "human", the Yanomami understand "anthro" as a malevolent, "powerful non-human with deeply disturbed tendancies and wild eccentricities." One such "anthro", Jacques Lizot, was called Bosinawarewa by the Yanomami, which means Anus Eater. Lizot’s pedophilia became so notorious among the Yanomami, that they coined a new word for sodomy: Lizo-mou - "to do like Lizot." The child-molester Lizot's enterprise of 25 years among the Yanomami was funded by the French state.

In general, Venezuelans and Yanomami alike remembered the "anthros" for the most outrageous behavior, even though, as Tierney emphasizes, "these were normal anthropolgists." Like J.P. Harrington among the Chumash (who also practiced sodomy – on his wife) the anthropologists were extremely envious and competitive of each other’s work. The Venezuelan anthropologist Jesús Cardozo recalled: "Anthropologists were chasing each other around with shotguns. Each had his own fiefdom. Villages were named for Lizot and Chagnon, as though they were great Yanomami chiefs. And the anthropologists’ villages took on their personalities. Chagnon’s Yanomami were more warlike than any other group; Lizot’s village became the capital of homosexuality." *

Yet again, for these terrible deeds, for this utter disgrace, anthropology is answerable.

____________________________________________

* Patrick Tierney, Darkness in El Dorado

W.W. Norton & Company, New York, 2001

Napoleon Chagnon's response to Darkness in El Dorado, pdf 142 pages

Although Lizot is utterly contemptible, I also found Chagnon to be contemptible in the film. His arrogance and pride have seemingly not been effected by the harsh international criticism which he has faced. Nor his narcissism. In an interview he shamefully compared himself to Galileo, despite there being very much that puts him in another class than one of the greatest scientists of all time. While visiting Florence Chagnon stopped in front of the villa at Arcetri, where Galileo was condemned to house arrest in 1634 for heresy until his death in 1642. Chagnon said he looked up at the window on the second floor and, filled with self-pity, wished to believe that he too was being unjustly accused by an evil papal establishment which would require 400 years for exoneration. The documentary corroborates Tierney’s initial accusations made ten years ago. Chagnon believes that he, not the Yanomami, is the victim!

My second Acta Americana article, an answer to Brian Haley’s attack in the same journal of my "Western Gate" article (see link below), has recently been published. Two additional articles by Haley and his colleague John Johnson have also been published in the same number of this journal, again attacking my credibility. I have no more time to spend on this debate. I steal time from my other projects nonetheless to inform my readers that Humqaq, also known as Point Conception, is a part of an oral Chumash tradition that is very likely thousands of years old. It is a vast symbol spanning millennia, like Avikwame on the Colorado river, the Mount Parnassus of the Aha Macav (Mohave) people.

The story of the Chumash Western Gate has the odor of extreme antiquity. BH persists in his losing battle to spread the lie that the Western Gate was recently “invented” by “neo-Chumash” who had problems with drugs, divorces and other human woes, and who, in their delirium, coined the term “western gate”. According to BH, these people live out their lives in self-delusion. Now he has seen his own problem. Only courage can help him to acknowledge it. His second attack on Dr. John Anderson, certain Chumash leaders, and myself, will prove to be his undoing. In my second article, he and JJ found errors I committed in the use of a Chumash name and incorrect dates for the native uprisings, and the rapes, floggings and tortures routinely committed on Native Californians at the missions and presidios. But as JJ concedes, these small errors do not effect my main point of contention with them: Humqaq is an extremely ancient phenomenon which has survived in an extremely ancient Chumash oral tradition. Neither BH nor JJ were able to deny this in their latest attack against me. However, JJ was able to mock my Slavic surname, Radic becoming Radic’al in the title of his article. Ho, ho, ho…

Now, to the crux of the matter: their theory that the Western Gate was invented in the 1970s by self-deluded misfits to whom they have given the name “neo-Chumash” will not be long-lived. JJ and BH both possess more factual knowledge about this culture than I. But they misuse their knowledge. BH again mocks me for having Humqaq as a sacred calling. He protests that a report written as a sacred calling is inappropriate for a scientific journal devoted to... yes, sacred callings in various aboriginal cultures throughout the Americas. This reasoning is hard to follow, and indeed appears utterly stupid. One of the journal’s main editors is Professor Emeritus Åke Hultkrantz , known throughout the world for his profound insights into the spiritual teachings of Native America. I was given full support by Prof. Hultkrantz in my second Acta Americana article. Apparently, BH believes he knows better than this firmly established patriarch of anthroplogy! J.P. Harrington’s astounding research among very many tribes throughout California can only be seen as a sacred calling for Harrington himself. Shall BH and JJ now mock Harrington for this “vice” as well?

Strangely, BH and JJ did not address the damning facts in Chumash spiritual leader Paul Pommier’s complaint in the appendix to my last article. “You must remember when a possum is cornered it becomes very vicious and has no where to go but to attack.” (Opening sentence of Paul Pommier’s complaint.) This complaint by a highly respected Chumash spiritual leader was not considered by BH and JJ because it would be very embarassing for them to do so. JJ would be obliged to explain why Paul Pommier, his former collaborator, chose to reevaluate his trust in JJ and revoke it. This respected spiritual leader is even acknowledged by the Doubting Thomas JJ as having impeccable genealogical proof of Chumash ancestry. He unequivocally denounces the use of the derogatory term “neo-Chumash” by these two anthropologists. Does not this clear-cut judgement of a widely respected Chumash spiritual leader register in your academic minds? Paul Pommier continues with his complaint: “Too often they have learned about our culture by scavenging from our ancestors’ graves.” JJ, curator at the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History, is well-aquainted with the boxes of human remains housed at the museum, as well as the rage this evokes in Chumash descendants today. “They have educated themselves by desecrating our burial lands.”

As for the blunder of BH, Paul Pommier, acknowledged by both BH and JJ as a bonafide Chumash leader, states that the Chumash people owe him nothing: “We owe these scholars like Haley, who claim the exclusive federal role of ‘delineators of identity’, nothing.”

Whether an observer can maintain "scientific objectivity" while examining cosmology and culture is questionable. Chumash descendant Mike Khus has written of this in his article on "anthropological nihilism":

“This debate reflects the broader issue of whether anthropology as practiced today, is capable of scientific objectivity on the level of other disciplines such as theoretical physics (it clearly is not) or whether it is merely an ‘interpretive art’, and is therefore not reliable or authoritative for purposes of public policy. [...] Neither have they [anthropologists] flinched from making it their business to meddle in the internal affairs of the Chumash community, deliberately targeting those Chumash families & individuals who challenge these same anthropolgists when sacred religious sites are threatened by the latter's irresponsible actions.”

Update,

(Read the entire article on John Anderson's webpage, as well as Dr. Anderson's answer to Haley)

ISHI

Still another book on Ishi has been recently published, Ishi in Three Centuries (2003), a collection of 22 essays and testimonies edited by Karl Kroeber and Clifton Kroeber, sons of Alfred and Theodora Kroeber. In his review of this latest book on Ishi, Peter Nabokov has both praise and criticism to mete out. Nabokov remarks that previously unpublished material testifies that Ishi “was remarkbly intelligent, surprisingly sweet-tempered, and innately dignified, facing his fate with heartbreaking equanimity.” (News from Native California, Spring, 2004)

In this book we learn that at Ishi’s death, Alfred Kroeber’s first reaction was the right one: to totally forbid a scientific dissection of Ishi’s body. From Europe he wrote: ”We propose to stand by our friends. If there is any talk of the interests of science, then say for me that science can go to hell.” Had Kroeber stood firm in his resolve, posterity would not have subjected him to harsh condemnation for lack of character. Alas, he did not stand firm, and his words were mere talk, not backed up by action, or in this case, non-action. Ishi’s brain was sent to the Smithsonian Institution through the efforts of Kroeber, who chose not to stand by his friend.

Nabokov notes that the editors of Ishi in Three Centuries took every opportunity to put “family-or-profession-justifying spins” on their commentaries. “One gets the sticky impression that the Kroebers still regard Ishi’s legacy as something of a family franchise. Sometimes it seem’s the man’s dissection still goes on.” Nabokov continues: “Plowing through this book’s tortured arguments and reinterpretations, I could not help feeling that perhaps what Ishi most deserves now is silence.”

Amen. But I doubt that we are mature enough for this silence, as Ishi was mature in the sacred silence about his name. After centuries of of trans-continental genocides, we need centuries to verbally deal with our collective shame and disgrace before we can rest in silence. My personal belief is that the epic crimes committed against Native Americans for long gruesome centuries cannot be expiated. Despite status as the only global super-power, high technology that produces atom bombs, sends men to the moon, and makes possible the overthrow of a foreign government at whim, the United States does not possess the power for expiating these genocidal crimes. Ishi’s enigmatic death mask smiles down at us as if saying: the gift of Turtle Island was bestowed on the Euro-Americans as pearls before swine.

Update, June 13, 2004

A particularly volatile situation developed after a local newspaper charged improper student handling of Chumash skeletons, dug up through publicly funded archaeological projects. Bones from innumerable burials had been scattered together in a large laboratory basin for examination by undergraduates, who routinely handled them without faculty supervision. Not unexpectedly, Native American students reported numerous incidents of disrespect by non-natives.[…] Lack of cooperation from the department led to continued bad publicity. It seemed like everyone else I knew in the university was appalled by the department's obstinacy, since similar confrontations were occurring nationwide as native religious leaders from Florida to Alaska sought legal rulings restricting academic access to native graveyards and other spiritual sites.

Many Chumash graves have been desecrated, often without the people responsible understanding that they were doing something forbidden. John Anderson writes of an atmosphere within the anthropological community from its very birth in which the native peoples of the continent were regarded as inferior, uncivilized and barbaric. Anderson cites numerous examples showing how Alfred Kroeber himself was guilty of this error, which has increased the suffering among California’s Indigenous Nations. One could almost say that this arrogance and pride at the core of academia is also behind the calamities we as a nation have brought down on the world and ourselves, and from which we will most likely not recover.

One arrives at the realization that no Euro-American, despite a Ph.D in anthropology and an entire career behind him or her, can have any other view of these cultures than one colored by European civilization. In his introduction to the Luiseño singer Villiana Calac Hyde's songs, Eric Elliott states: "In order to fully understand the culture of a given community or individual, one has to be a member of that culture." (Surviving Through the Days, edited by Herbert W. Luthin, University of California Press, 2002)

Luiseño women at Mission San Luis Rey

(San Diego Historical Society)

Note: At the peak of its prosperity,

Mission San Luis Rey was one of the largest

and most populous missions in both of the Americas.

The Eurocentric racism of Kroeber, Harrington and the university system is a sad fact. The good news however is that this racism embedded in white studies of Native California (and the rest of the continent) at the university level can be cured. But the cure is impossible if this arrogance and pride are not regretted and erradicated. And then, with humility and wisdom, the true nature of the cultures of our state can be fully appreciated and respected.

Update, June 21, 2004

However much one can object to what Anderson calls “Powers’ degrading language,” his book is invaluable for Native Californian studies. Without it, something profound would be missing in California ethnology. I doubt that Anderson would condemn Malki Press for having republished Padre Boscana’s Chinigchinich in 1978 from the 1846 version, although Boscana’s extreme racism can be compared to that of Himmler, Goebbels and Hitler. Without this valuable text, republished by a native-owned publishing house, we would never have learned about this man-god from Puvungna (Rancho Los Alamitos, near Long Beach). This republication was obviously not a “low point” in California ethnology, although its author is much more reprehensible than Powers.

[Note: Responding to my comment, John Anderson clarifies that he did not mean to imply that the old racist texts should not be published at all. He as well considers them extremely valuable, both for the information they contain, as well as for a demonstration of the racist attitudes prevalent at the time and which led to what we have today; but he confirms his opinion that any republication should be carefully prefaced. It can be argued, however, that Robert Heizer provided just such a cautioning preface. He wrote: "But Powers, as a man of a century ago, could scarcely fail to reflect in his writings (which we must not forget were directed toward a body of contemporary readers) the low opinion which Americans generally held about all Indians." As a reader of Tribes of California I am satisfied with Heizer's preface, which duly cautions against Power's racism.]

I agree with John Anderson that Powers is contemptible in his belief that the Native Californians belonged to “a humble and lowly race, one of the lowest on earth,” living in a state of “unprogressive savagery.” But refuting Powers’ report of cannibalism is nothing Anderson can do with scientific certainty. The chapter in Montaigne’s Essays called “Les Cannibales” refers to a practice that was prevalent throughout the Americas. J.P. Harrington also wrote of ritual cannibalism among certain southern Californian tribes, a reinactment of Coyote stealing the dead god's heart from the funeral pyre and eating it.

The degradation that Powers witnessed was also reported by chroniclers one century before him. When Powers wrote of the “degraded and unhappy offspring” of the Pomo, Anderson accuses him of being “insensitive.” But these children were like the victims of colonialism all over the world, impoverished and unhappy. Perhaps Powers’ comment was a sign of compassion? Robert Heizer wrote in his preface: "It is obvious, I think, that Powers genuinely liked the California Indians he was visiting and studying in the summers of 1871 and 1872, and was aware of their shattering experience of contact with the Americans from Gold Rush times, some twenty years before." Powers did indeed behold a degraded people. What he and some earlier chroniclers failed to understand was that this degradation was not intrinsic to native cultures, but to European cultures, most of all European Christianity. It is as if an outside observer were to judge Jewish culture by the degraded and emaciated Jews liberated from Auschwitz, instead of judging German culture as the author of this degradation.

The merest contact with Europeans degraded these peoples, just as California as a natural paradise was degraded by these same Europeans. Therefore, the academic pride of being “civilized” carries with it, firstly, the deadly consequences of this deadly sin. Secondly, it ignores that “civilization,” as both Catlin and Baudelaire observed, is about degradation of the individual, the society, the natural environment and the spiritual state of mankind.

Robert Heizer’s cautioning preface to Tribes of California mentioned above has no counterpart in the southern Californian classic Chinigchinich, republished by Malki Press in 1978 with a preface by William Bright. Bright does not comment on Boscana’s very harsh racism, nor does J.P. Harrington in his lengthy and extremely detailed notes to this work. The anthropologists instead commented on the unique importance of this text: “This is after all much the most important ethnographic document on the California Indians left by the Franciscans who converted them.” (A.L. Kroeber) “[It] is easily and by far the most ethnological of any of the essays or accounts written in the Spanish language during the Spanish period of the history of the Californias.” (J.P. Harrington) Bright notes that Boscana’s “rather bizarre spelling Chinigchinich […] has, by now, too much tradition behind it to be discarded.” Harrington suggested that it be pronounced “chee-ngich´-ngich.”

Robert Heizer’s cautioning preface to Tribes of California mentioned above has no counterpart in the southern Californian classic Chinigchinich, republished by Malki Press in 1978 with a preface by William Bright. Bright does not comment on Boscana’s very harsh racism, nor does J.P. Harrington in his lengthy and extremely detailed notes to this work. The anthropologists instead commented on the unique importance of this text: “This is after all much the most important ethnographic document on the California Indians left by the Franciscans who converted them.” (A.L. Kroeber) “[It] is easily and by far the most ethnological of any of the essays or accounts written in the Spanish language during the Spanish period of the history of the Californias.” (J.P. Harrington) Bright notes that Boscana’s “rather bizarre spelling Chinigchinich […] has, by now, too much tradition behind it to be discarded.” Harrington suggested that it be pronounced “chee-ngich´-ngich.”

This amazing story has fascinated me since I first came into contact with it 25 years ago. The translator, however, did not seem to appreciate it. I think of Richard Wilhelm's translation of the ancient Chinese classic on meditation called The Secret of the Golden Flower, which was also scorned by the translator, who lacked the necessary perception to appreciate the wisdom of this text. Such is the case in Boscana’s introduction to his Spanish translation of this Tongva/Acjachemen epic. The Spaniard did not have the necessary perception to appreciate the wisdom inherent in this true story of a holy man who surpasses all others we know of in the available literature. (Bright and Kroeber, however, doubted that Chinigchinich was an historic human being, not making the connection between the man and the god which is prevalent in mythologies throughout the world.) Boscana’s racism did not evoke any comments from William Bright nor J.P. Harrington, even when he referred to the Acjachemen people as “monkies,” “more like brutes than rational beings.” Nor did they comment on the very important data neglected by Boscana: who were the bards who told him this story? What was the nature of their tradition? How does it relate to the god in question?

Bright comments that Harrington’s aim was “to clarify and to flesh out the Boscana text with every bit of ethnographic and linguistic information that he could obtain.” Despite his near-lunatic scrutiny of this text, the glaring fact of Boscana’s contempt and ill will was overlooked (or ignored) by Harrington. And yet, the republication of Boscana’s text comes as a blessing. The priest was unwittingly the tool of the very people he scorned, an ignorant messenger whose purpose was to present us with southern California’s principle myth. Little does his contempt matter in this respect. It is surprising, however, that neither Harrington nor Bright chose to condemn Boscana’s racism.

Bards from the newly founded village of Acjachemen had carried the epic of Chinigchinich with them from the north (the area called San Gabriel Valley today), where it had its origins among the Tongva. When the Spanish took over their territory by force, used them as slaves to build a mission, and put Boscana in charge of it, the mighty story was injected into western culture like the venom of a rattlesnake, for Chinigchinich the Chastizer is the god of venemous animals. In this story of a god who lived a while in human form, the significance of his birthplace Puvungna – “the gathering place” – to southern California is like that of Bethlehem to Palestine.

Boscana wrote that in December, 1823, an in September, 1825, two comets appeared and were visible for a month. The Acjachemen people around mission San Juan Capistrano told the priest that they were departed chiefs, and that “they denoted some important change in their destiny.” Some thought it boded well, that they would return to their ancient way of life. The elders, however interpreted the comets as boding ill, “that another people [Americans] would come who would treat them as slaves and abuse them; that they would suffer much hunger and misery; and that the chief thus appeared to call them away from the impending calamity.” What seer or prophet could stand firm against Manifest Destiny?

Alfred Louis Kroeber wrote that the Tongva were considered “the enlightened ones” by the surrounding tribes, and he himself referred to them in his Handbook of the Indians of California as “the wealthiest and most thoughtful of all the Shoshoneans.” Chinigchinich was the principle deity of the Tongva, Acjachemen and certain other peoples who shared cosmogonies in southern California. Chinigchinich supplanted the earlier deity Wewyoot. This earlier deity, in many of the myths, was bewitched by his own people, killed and his body burned on a funeral pyre. Coyote stole his heart before it was consumed by the fire and ate it, becoming both devil and god for many tribes.

When Chinigchinich was a boy in Puvungna, he was called Saor, “before-he-learned-to-dance,” a term used also to refer to the uninitiated. When he became Tobet he established the rites of dance, epic poetry, painting, and the laws of Tongva society. Tobet also was used to refer to the headdress worn by the ritual dancers. John Peabody Harrington has also written that Tobet was the name of the first man ever to sing and perform singing ceremonies (Jack Rabbit in the myths). As Quaoar he dwells among the stars after having danced his way into heaven. So dreaded and sacred was his third name that it was rarely spoken, and then only in whispers.

After many years of studying the available material on the Tongva culture, I have found no answer to the question of Chinigchinich's age. Scholars vary in their beliefs, some seeing this man-god as a conscious imitation of the christian man-god (as did Kroeber), and others seeing him as extremely ancient, in existence long before the coming of the Spaniards in 1542. Still others see Chinigchinich as a European shipwrecked in the 16th century with a knowledge of judaism, christianity or buddhism. (However vain this alternative seems, it brings to mind the stranded 16th-century Englishman, Anthony Knivet, who became a war chief to the Tupinamba tribe in Brazil.) Similarities between the spiritual teachings of Chinigchinich and other teachings in the world need not suggest contact between the different cultures. Spirit, like blood, is common to all humanity, and similarities in spiritual teachings throughout the world often arise from this one common source.

William McCawley lists these various guesses as to the age of Chinigchinich in his book The First Angelinos, and writes that the Tongva cosmogony “may represent a religious system of considerable antiquity.” Those scholars who wish to see European influence in the story of Chinigchinich perhaps believe that spiritual profundity is impossible among “savages” and must be a European import. On the contrary, such spiritual profundity is not visible in the occident, with the exception of ancient Greece, where the artistic principle was also the prime mover of society. The man-god Dionysos filled a similar need in Greece as Chinigchinich in California, and indeed, is still filling this need even today, in the forms of Drama, Dance, Painting and Poetry.

Chinigchinich provided his people with sacred rites and a divine blueprint for musicians, dancers, ground painters, bards, healers, warriors, sorcerers, chieftains and prophets. When he appeared to the tribal elders the first time, it was as a spectre who quickly disappeared again. He reappeared, and disappeared again. The third time he remained to instruct them. (excerpt from The Whetting Stone.)

My 25 years of studies of Native California have been undertaken as an artist and not a scientist. (This is relevant to the discussion of Chinigchinich above, who was the prototype of aboriginal artists.) Even though this has meant that anthropologists refuse to take me seriously, there are parallels of artists undertaking studies in an area considered reserved for scientists. The in-depth studies of occidental culture carried out by Robert Graves and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe come to mind, as well as George Catlin's phenomenal opus. The two distinct methodologies – that of science and that of Art – involve completely different motivations for study.

In Art, the more you learn, the less you know about the mystery. In science, accumulated knowledge leads the investigator to believe that he or she knows more and more about the mystery under investigation – for example, the universe. Despite all the knowledge accumulated about the galaxies, quasars, stars and our solar system by scientists, I still look up at the starry night sky in total ignorance. I am comfortable with my ignorance of this mystery. Scientists, however are very uncomfortable not knowing. They gather knowledge as a means of alleviating this discomfort, and wish us to believe that their “Big-Bang” theory need not be doubted. They know, period. (Alan Watts has called scientific theories about the universe myths among other myths.)

However, the most obvious and all-pervading essence of the universe – Spirit – has been left totally out of the scientists' calculations. How can I but doubt their competence in this matter? In the human sphere, this translates into the sacred. The taoist sage Chuang Tzu believed that knowledge is a by-product to spiritual attainment. What good is knowledge without attainment? Chuang Tzu felt closer to the universe in a state of not-knowing. A mystery is not knowable. The thousands of years of Chumash culture are not knowable. The sacred is not really given proper treatment by science. It is not a scientific subject. It requires being comfortable with one’s ignorance.

The transgressions of scientists toward Native American cultures for as long as they have been studied derive from this faulty knowledge of the sacred which is intrinsic to science. We know that science does not deal with Spirit, for it is unscientific to do so. Alas, Spirit is strangely unaccounted for in all branches of science. It is neither seen in the elaborate formulas nor in the far-from-eloquent language used tediously in science. Those scientists who have attempted to make utterances on the nature of Spirit often make fools of themselves. Scientific methods are of no use to them here. Tibetan buddhists see science as having made major contributions to minor needs. Major needs – needs of Spirit – receive no attention from science. And after all, the universe is above all other things a spiritual phenomenon.

Sakta rinner vanvett i människornas hjärtan.

Gyllene dårskap famnar människornas tröskel med unga rankors lidelse.(Slowly insanity courses in human hearts.

Guilded lunacy embraces humanity’s threshold with the ardor of young vines.)— Edith Södergran

”The Stars are Swarming”

translated from Swedish by Theo Radic

(from Selected Poetry of Edith Södergran)

Update, August 11, 2004

ART AND SCIENCE

But such good will has difficulty prevailing over the greater ill will that inflicts science, and to a lesser degree, Art. Levi wrote that “between ‘the two cultures’ there is no incompatability; contrary, there is, at times, when there is good will, mutual attraction.”* This can be seen when the mind of Einstein confronted the mind of Bach. However, a certain academic haughtiness in Einstein made him equate what he saw as “beauty” in physics with that of Art – a fatal error. Whatever it may be, the “beauty” of physics can never approach the profundities of the Beauty of Bach’s music and the rest of the Art of human kind.

The individuals of Native Californian cultures versed in the uses of plants, weather predictions and star-gazing were compared to western scientists by the scientist Florence Shipek (California Indian Shamanism). The native men and women of knowledge possessed and possess knowledge immersed in the harmony of the Way, a trait lacking in the compartmentalized sciences of the west. Western scientists are strangers to the discipline of Harmony. Harmony is not something that falls into your lap automatically simply because you appreciate Art. Harmony is a discipline. An initiation. It is perhaps the most difficult of all goals to attain. The harmony that results in the initiation of the artists is then passed on to the rest of the community, whether they practice the musical, poetical, herbal, star-gazing, or rock/canvas painting arts.

The difficulty in truly achieving Harmony (which could be scientifically called balance between the right and left sides of the brain) can be seen in the lives of the occidental masters. Who more than Beethoven knew the secret technique of Harmony? And yet he made a mess of his life, tormented his brother's widow, snatched her only child away from her because of his power as patriarch, and, trying to raise the poor boy as his own, drove him to a distant hill with grazing sheep, where Beethoven's nephew put a bullet in his skull (he survived). He could not live up to the high standards that his tyrannical uncle imposed on him. So difficult is the task of bringing Harmony into the workings of daily life – not even Beethoven could do it!

The similarities between the modern sciences and what Shipek sees as sciences among the Native Californians are clearly evident. The differences as well are clearly evident. Concern for the sacred is where aboriginal sciences differ drastically from western sciences, which, when practiced correctly, are in fact arts. The ceremonies involving the solstices, equinoxes and blossoming stages of food sources were central for Native Californian societies. In them is concentrated genuine concern for the sacred by the people of the community. Lacking this widespread concern for the sacred, and uninitiated in the discipline of Harmony, scientists present us with a fragmented world-view.

There is a natural Chumash shrine frequented by tourists and university people near Tranquillon Peak on Vandenburg Air Force Base. (Once tranquil, Tranquillon Peak has been “developed” by the military, with bulldozers and earth-moving machines having permanently deformed its ancient silhouette at sunset.) The sacred shrine today is called Window Rock Cave. At the winter solstice (a time of paramount importance to the Chumash), the light of the afternoon sun enters the natural “window” of the cave, to illuminate petroglyphs engraved on the cave wall, a few days before and a few days after the solstice. The winter rays of sunlight snake along the walls obliquely, brushed dust-like over the mineral grains of the petroglyph of the sun. Knowledge of such natural coincidences is the profound talent of the Chumash, a talent still thriving today. But those modern Chumash who are initiated into the ancient rites have difficulty maintaining the sacred status of Window Rock Cave (just as Apollo's adepts no longer can maintain the sacredness at Delphi today). In both cases, the tourists are in the way.

A few years ago a female museum docent who visited Window Rock Cave with her colleagues during the winter solstice was quoted in the newspaper: “To think that the Chumash could find something like that is amazing. It's not exactly a holy place, but it’s something similar to it.” (Santa Barbara News Press 22.XII.92) It takes people initiated into the arts of the Way to understand that this is indeed, and with no doubts whatsoever, a holy place. Why did the scientist not understand this? (excerpt from Crazy Devil Sweeping)

Update, February 23, 2005

ROCK ART AND SCIENCE

"The Birth"

Chumash rock painting in Sespe

photo by Richard Cordero

There is a very fine line between science

and a bold flirtation with the speculative.

– Brian Fagan, Before California

Fagan writes: "The sad conclusion is that we can never hope to understand all the roles that rock art played in ancient California life." As a visual artist I do not regard it as "sad" that the significance of rock art will never be truly known in all its aspects. The fading and eventual disappearance of the painted image are important aspects of the art. Paintings on rocks, canvas or paper are more likely to be regarded as ”precious” by non-artists. Before he died, Claude Monet destroyed many of his paintings as unworthy to be left to posterity. Art dealers, art historians and other non-artists would have thought it a pity that these paintings were destroyed, still seeing them as precious objects to be coveted. Cézanne left oil paintings in the back country of Aix-en-Provence to be battered by weather and obliterated like last years autumn leaves. The covetousness of non-artists towards works of art is irritating to artists, and is is very evident in the academic debate over California’s rock art.

Brian Fagan begins his chapter on rock art with a fictitious story of a Chumash ”shaman” at Condor Cave in the Santa Ynez mountains in AD 1200, as if he were beginning a novel: "He sat cross-legged in the dark cave... As he waited [for the sunrise of the winter solstice] he sang quietly, etc." I have hiked to Condor Cave and photographed the images painted on the cave wall. I can’t say if the painter sang quietly on the morning of the winter solstice in the year AD 1200, or even if the cave was visited by a painter that particular winter. The archaeologist quotes the expert on Chumash rock art, Campbell Grant, who was himself a gifted painter: "The creators took satisfaction in a job ingeniously conceived and well-executed." According to Grant, Art satisfied the desire of the creator "to make a pleasing image on a rock where nothing had existed before, an image that might carry part of the artist into the most distant future." (Campbell Grant, James W. Baird, and Kenneth Pringle, Rock Paintings of the Coso Range, Ridgecrest CA, Maturango Museum, 1969) I find this evaluation by Grant to be very well-put, and don’t see why the issue need be more complicated than "to make a pleasing image on a rock where nothing had existed before."

|

|

Disagreeing with the artist Grant’s view, the scientist Fagan cautions: "We must not fall into the trap of thinking about art through Western eyes." I have painted since I was one year old. My evolution as a painter paralleled that of art history in general, beginning with my prehistoric period as a one-year-old-clutcher-of-crayolas, groping through Egyptian and Greek periods; a Renaissance period; and then neo-classicism, romanticism and naturalism; impressionism and fauvism; cubism and abstract expressionism. I regard Grant’s view of the motivation for creating rock art — to make a pleasing image — the raison d’être of all painting since the Altamira and Lascaux caves were decorated 30,000 years ago. I regard these prehistoric painters in Spain and France as the precursors of Velasquez and Picasso, Chardin and Matisse.

The "ferocious debates" over rock art by non-artist scholars overlook the "inner necessity" common to all visual art. Fagan cites "sympathetic hunting magic" as another motivation for rock art. This can be carried further to include the broader concept "participation mystique" used by depth psychologist Erich Neumann in his classic works The Great Mother and Origins and History of Consciousness. Erich Neumann’s insights into Art and creativity are profound, much more so than those of his elder colleague Carl Jung. Neumann borrowed the term “participation mystique” from a German author of the 19th century to denote the manner in which the artist “participates” in the unity of nature to such a degree that he is no longer separate from it.

Neumann's research clearly shows how there are similar motivations for creating in a child drawing with his crayolas and a prehistoric cave painter tens of thousands of years ago. The universal origins of creativity in human beings unite different cultures and epochs. With the insider’s deep knowledge of the art of painting, Vassily Kandinsky (1866-1944) explained this clearly as the Principal of Inner Necessity, which applies to rock art as well. Considering the vast degree to which this vital principle is ignored today (for it is the credo not only of the artist, but his connoisseurs as well), it is best to cite it in full:

1. Each artist, as creator, must express that which is unique to him. (Element of personality.)

2. Each artist, as child of his era, must express that which is unique to that era. (Element of the inner value of style, composed of the language of the people, as long as they exist as a nation.)

3. Each artist, as the servant of Art, must express that which is, in general, unique to Art. (Element of pure and eternal Art that one finds among all human beings, among all peoples and all times, that appears in the opuses of all artists, of all nations and all eras, and obeys no law of space and time as the essential element of Art.*

|

|

Brian Fagan's chapter on "shamans" in Before California emanates a clear comprehension of the spiritual realities of these creative individuals. But one can go further - not to complicate, but to simplify. For example, when Fagan writes that "shamans... mediated between the living and spiritual realms," one can also understand these two "realms" as one and the same. Spirit is intertwined with Life. When it departs, death is the result. Thus, "the living and spiritual realms" are in fact one. When Fagan, like so many other writers, refers to the "power" of the "shaman", we can simplify this mysterious word by calling it creativity instead.

Creativity, like the medicine people's "power", is a very rare phenomenon in human societies, although it alone is their architect. Nothing in any other human discipline surpasses the Art of human kind for in-depth confrontation with Spirit. Bach, da Vinci and Shakespeare are some of the best examples of this in our civilization. Remove Art from religion — all the poetry, oratorios and other great music, the paintings, architecture, divine inspiration and psalms of poets like Isaiah and David — and religion is stripped of its "power", of its spiritual legitimacy. The same for creators among the Chumash or other Native American cultures. Their "power" is very simply the creativity of the artist. Their "spirit helpers" correspond to the Muses of western artists.

Despite the differences between our culture and ancient Californian cultures, it may be said that in studying them we are looking into our own past, as Åke Hultkrantz wrote: "One reason those of us who are not Native Americans study their religious beliefs and customs is to recover a religious heritage that we all, as descendants of hunters in ages past, share." (Native Religions of North America, Åke Hultkrantz, Harper, San Francisco, 1987.) Hultkrantz has specified that shaman "is a technical term for a certain type of medicine man in some humanistic disciplines." (personal communication) In the universal use of language, it becomes less appropriate. At the local level of society, in all parts of the world, for time immemorial, there have been creative individuals within the community different from the others, who put their creative powers at the disposal of their brethren, often receiving no thanks and even punishment for being their benefactors. In our civilization they are known as artists. To call this global phenomenon "shamanism" is to pigeon-hole a great mystery into a tiny container, like Aladdin's imprisoned genie in the lamp. If the paintings in the caves of Lascaux, Altamira and California are universally acknowledged as Art, then the strange beings who painted them were artists, a far better description than "shamans".

Hultkrantz specifies that "there are few persons among the North American Indians who can be designated as shamans in the Siberian sense, but many who demonstrate specific shamanic traits." ("The Specific Character of North American Shamanism," Åke Hultkrantz, European Review of Native American Studies, 13:2 1999) Now we not only have the scientific distinction between "shaman" and "medicine man," but also a third category of one possessing "shamanic traits". Indeed, such distinctions are scientific, and imply a precision that can be relevant in chemistry or physics, but which is irrelevant in the domain of the spiritual, a thoroughly unscientific domain.

A recent book on rock art by David S. Whitely is entitled The Art of the Shaman. ”The Art of the Tribal Artist” is basically what is meant by this title. Reviewing this book, Ken Hedges, curator of of California collections at San Diego Museum of Man, agrees with Whitely’s "shamanistic interpretation of rock art." He believes that "we have much to lose if shamanistic interpretation is removed from consideration in rock art research." From an artistic perspective, we have much to gain examining the world’s art without applying ”shamanistic”, ”psychoanalytical” or any other preconceived scientific notions of art. What anthropologists term "shamanism" is in fact a stage in the evolution of Art. In the Cahuilla language (still spoken in the valley of my birth) the term puvalam, usually translated as "shaman", is said to mean "initiate". The artist is a life-long initiate. The practice of all the arts requires formal initiation. In certain cultures the initiation involves secrecy. Fagan writes: "Eyewitness accounts of painting are rare." This could have to do with ritual secrecy surrounding the initiation into this art. One eyewitness stated to Harrington that the painters painted their spirits [anit] on rocks "to show themselves, to let people know what they had done." (The Rock Painting of the Chumash, Campbell Grant, UC Press, Berkeley, 1965) This could have been the motivation for Michelangelo and other western painters as well.