William Finnegan | Gerry Lopez | Ricky Grigg | Mike Doyle | Miki Dora | Shaun Tomson | Willem de Kooning

William Finnegan | Gerry Lopez | Ricky Grigg | Mike Doyle | Miki Dora | Shaun Tomson | Willem de Kooning

Barbarian Days: A Surfing Life

William Finnegan

Corsair, London 2015

The other books on surfing which are discussed on this webpage came to my attention directly from the various media uniquely dedicated to surfing. It is a very specialized and exclusive world like those dedicated to, for example, tennis, horseback riding or mountaineering. In his book Maverick’s, former editor of Surfer Magazine, Matt Warshaw, described the art of big wave surfing as “a fairly obscure and cloistered pursuit,” (at least before the highly publicized drowning death of Mark Foo in 1994). Barbarian Days however came to my attention directly from the universal domain of Literature with a capital “L,” despite its devotion to surfing at the most elite level. It has that extra “something” that only a Pulitzer-Prize winning author, who is as well an elite surfer, can give to the art which he called “the disabling enchantment of surfing.” I have commented previously on the extraordinary literary talent of Gerry Lopez, whose Surf is Where You Find It (see below) was until now the best book, artistically speaking, that I had read on surfing. Barbarian Days, published only last year (2015), is a masterpiece of non-fiction.

In 1992 a long two-part article by William Finnegan entitled “Playing Doc’s Games” was published in the New Yorker. Twenty three years later, the memoir based on it that this New Yorker staff-writer was rumored to be writing was finally published. One year later the book fell into my hands by pure chance. Despite winning the Pulitzer Prize and international acclaim, it received little or no publicity in Sweden, where I live. Stockholm, summer 2016. I rode my bike to the municipal library on Sveavägen to return the biography of Maurice Ravel which I had borrowed. What will my next summer reading be? I wandered up and down the library aisles, looking for a non-fiction book that would catch my eye. I pulled several possibilities from the shelves, thumbed through them, and put them back on the shelf. Nothing interested me. I was ready to leave the library empty-handed. Then I randomly pulled a book from the shelf with a cover showing two surfers lounging on what seemed to be a front porch. Barbarian Days. Hmm… sounds a bit like my youth before I became so terribly domesticated in a big European city. I checked the book out with my electronic library card and returned home.

As it was reading the autobiography of legendary surfer Ricky Grigg (see below) I was again put into direct contact with my years growing up in southern California and surfing up and down the coast. And much more. Like many surfers, William Finnegan was possessed: “I did not consider, even passingly, that I had a choice when it came to surfing. My enchantment would take me where it would.” He went on to do the things that many of us average surfers only dreamed of doing, surfing in Hawaii, the South Pacific, Indonesia, South Africa and Peru. Like the surfers in the legendary film Endless Summer who found the perfect wave at Cape St. Francis, South Africa, Finnegan found the perfect, empty wave with his friend Bryan Di Salvatore in 1978, off a tiny island in Fiji called Tavarua. Much as he feared thirty-eight years ago, an exclusive surfing resort that costs about $400 a day has now been built on the once uninhabited Tavarua. Although his story evokes Endless Summer, it goes far beyond it as art. “Indeed, if the book has a flaw, it lies in the envy helplessly induced in the armchair surf-traveler by so many lusty affairs with waves that are the supermodels of the surf world.” (NY Times July 13, 2015)

The Irish-American Finnegan mentions reading Finnegan’s Wake in his youth, and very clearly holds master writers like James Joyce in high esteem, as he holds master surfers like Mark “Doc” Renneker (protaganist of “Playing Doc’s Games”) in high esteem. (The new Finnegan’s “wake” is the wake of the author’s surfboard.) This is the unique quality of Barbarian Days, the mastery of two arts side-by-side. Along with his studies he became what is called a “surfing junky” in the San Francisco surfing scene at Ocean Beach. (left: Finnegan surfing Ocean Beach)

After traveling and surfing all over the world, Finnegan was surprised to learn that there were hardcore surfers in San Francisco. “It was astounding to me that anyone learned to surf in San Francisco.” I too was surprised to learn that San Francisco can be named alongside Santa Cruz and Huntington Beach as a veritable city of surfers. Along with Santa Cruz surfers they go by the name Vermin, some of whom are toughened veterans of the biggest most brutal waves California has to offer at Maverick’s on Half Moon Bay. It is a cold and raw ocean that this southern Californian surfer encountered in the Bay Area, after his adventures surfing in warm tropical oceans where he never donned a wetsuit. In the big, violent, cold waves of Ocean Beach, even a wetsuit did not protect Finnegan from the bitterly cold water: “A broken leash and a long swim could spell hypothermia. Loss of sensation in hands and feet was already giving me trouble. I sometimes had to ask strangers to open my car door and put the key in the ignition, my own manual dexterity having been deleted by a surf.”

As a newcomer to San Francisco, Finnegan had as friend and mentor big wave surfer Mark “Doc” Renneker, one of the elite group of surfers who have mastered the colossal waves at Maverick’s. During one session at Ocean Beach, Finnegan and Renneker tired of fighting the fierce current in order to stay at the same sand bar where the waves broke, so they abandoned themselves to the current. They drifted three miles north as they surfed at various breaks haphazardly and then hitch-hiked home with their boards. Another time they were caught “inside” when a huge set rolled in, bigger than anything he had yet seen at Ocean Beach. His leashed snapped and now he was a lone swimmer struggling for his life, diving deeper and deeper under each new and bigger wave, stunned by each detonation above him, “a basso profundo of utter violence.” He finally emerged from he cold ocean and went home to bed. “Doc” Renneker stayed out four more hours.

Earlier in the book, in Missoula, Montana, Finnegan told his friends that he was headed west to California and then to the South Pacific, and would return from the east. A year or two later, after the splendid surfing adventures described in Barbarian Days, he hitch-hiked from New York to Missoula, Montana (“a long, cold, magnificent trip”). Finnegan had circumnavigated the globe on a whim. “For what it was worth, I was coming, as promised, from the east.”

Several times he referred to the novel he was working on in the midst of his barbarian adventures, finding quiet libraries where he could add a few more pages to his slowly evolving opus. I don’t know if he ever finished his novel, but having stopped reading novels altogether, I know that I would not have read it. Finnegan’s evolution as a writer went from being a writer of fiction to a writer of non-fiction. The non-fiction of Reality provided him with a well-composed narrative before he wrote a line. It was there, like a gem in the soil waiting for the miner to unearth it, more entertaining than an invented plot with invented events and characters in a novel.

That which interests me most as a reader of, say, Conrad or Melville, is not the plot with its fictitious events and characters (called a “brilliant lie” by Zola), but a non-fiction essence lurking between the lines that these ocean-bewitched writers truly experienced as seamen. One of my absolute favorite examples of American literature is Two Years Before the Mast by Richard Henry Dana, after whom Dana Point, California is named. This non-fiction narrative of a young Bostonian seaman who signs on to a clipper ship in 1834 to round Cape Horn to California and back to Boston, with its heroic trials and and jubilations, readily can be compared to Barbarian Days. The epic non-fiction narratives of George Catlin also come to mind.

Jardim do Mar, Madeira

In the chapter entitled “Basso Profundo” Finnegan relates a near-death experience at Jardim do Mar in Madeira in 1997 – one of the most suspense-filled passages I have ever read about big-wave surfing. The superb skill of his writing again makes me think of Gerry Lopez in his book Surf is Where You Find It (below) describing a moment of sheer terror while being overwhelmed by colossal waves: “If there was a time to call for Mama, this was it.” Finnegan, in a similar plight, describes the heightened sense of awareness that kicked in with a drowning death lurking close at hand. This heightened perception made Finnegan and his surfing buddy Peter Spacek keenly aware of how truly dangerous it was out there. The wave-hunters had become the wave-hunted in an instant.

Usually, as in Lopez’ case, being caught “inside” is the danger. In their case, it was being caught “outside,” totally exhausted, when the biggest waves of Finnegan’s career rolled in from over the Atlantic horizon as night was falling, making the option of paddling in for the day out of the question. The two were obliged to frantically paddle even further out into the darkening ocean: “We made it safely over the set. The waves, however, were the biggest waves I had ever seen from a surfboard.” This scene evokes the legendary drowning death of 17-year-old Dickie Cross on December 22, 1943 on the North Shore of Oahu. He and his companion Woody Brown as well were trapped “outside” on a colossal day when paddling in would be suicide. Woody survived and lived to old age and told the tale many times. Dickie’s body was never found. Finnegan and Spacek also survived by a hair.

Finnegan now calls New York City home. More surprising than San Francisco being a surf city, is New York as a surf city. He has enormous empathy for fellow humans, and has spent his life reporting on a variety of lives, sometimes in dangerous war zones in Africa or Latin America. This empathy adds color and depth to his descriptions of surfers and non-surfers alike. One native New Yorker and dedicated surfer who became his friend, John Selya, is a ballet dancer from the American Ballet Theatre, initially under the direction of Mikhail Baryshnikov, before he became a celebrated dancer in Broadway musicals. He is described as “an utterly remarkable dancer” by a New Yorker dance critic, and equally as remarkable a surfer by Finnegan: “His surfing is precise, aggressive, explosive – balletic.” His younger friend’s obsession for surfing is so intense that Finnegan admitted: “Selya makes me look half-committed.” After a long session of surfing in big winter waves on Long Island, each squinting from the ice particles flung into their faces by the off-shore wind, they quickly changed from wetsuits to street clothes in the parked car. Finnegan then drove Selya, star dancer in the musical Movin’ Out, to the stage door in Manhattan, where he “panthered in with minutes to spare.” (Not the usual surfer profile.)

In surfing history one refers to watermen – not moving over the ocean as sailors do, but in it. William Finnegan truly belongs to this Hawaiian, Californian, Australian, Peruvian and South African tradition of hardy watermen whose stories remain alive for generations, like the stories told and retold since Homeric Greece. Finnegan fortunately did not chose to write a novel about his experience. And Literature with a capital “L” is all the more enriched by his non-fiction.

I have not been equally as captivated by the New Yorker staff writer Willam Finnegan. Read more...

Surf is Where You Find It

Gerry Lopez

Patagonia Books, 2008

A word comes to mind seeing videos of Gerry Lopez surfing, snow-boarding or being interviewed: grace. In his autiobiographical book Surf is Where You Find It, he also demonstrates grace as a writer. In a psychopathic world, grace is not welcome. And yet, receiving “grace waves” from Master Marpa led to Enlightenment for the Tibetan bard Milarepa, wandering barefoot in the Himalayas, as Gerry Lopez wanders barefoot in the oceans. With parents who instilled in him a love of reading books as a child, and with a father who was a newspaper journalist, Lopez is equally at ease with a pen as with a surfboard. He is one of the rare surfers, like Ricky Grigg (see below), who writes his own story without the assistence of a co-author or ghost writer. He vividly portrays scenes that were never captured on film, and that would never have left the private story-telling mode of surfers, had he not written them down. The intensity is on the same wave-length as the Iliad and the Odyssey. One such scene involves his friend Herbie Fletcher out on a terrifying close-out day at Waimea on his “souped-up” jet-ski. It would have been near suicide for a surfer on a board to have been out on such a day, even though one was out and nearly drowned. The power of the jet-ski allowed for outrunning the huge waves, even though Herbie Fletcher too was in great danger. Lopez viewed the whole episode from the lifeguard tower with Herbie’s young son:

I watched the wave grow more in height as the thick lip, arrayed across the width of the Bay, pitched up and out. It landed with an earth shattering crash right behind him; the explosion seemed to blast him and his ski up in the air. Herbie’s body was fluttering like a flag, his hands on the handlebars his only attachment to the ski as the rest of his body flapped like a towel on a clothesline in brisk wind and his mechanical savior bounced like a ping pong ball in the whitewater.This amazing scene displays an uncanny instinct for the writer's craft. Lopez masters all the crafts that he undertakes, whether surfing, snowboarding, writing or practicing yoga. This is not always the case when great surfers move to other disciplines – like the art of painting.

However, Gerry Lopez’ mastery of the pen equals his mastery of Pipeline and G-Land on a surfboard, or his mastery of gigantic slopes of virgin snow on isolated mountaintops. In one interview he likened his snowboarding experiences to the tow-in take-offs on terrifying waves at places like Mavericks and Jaws. Being towed by a jet-ski allows the surfer to catch the wave far earlier than he could paddling. In fact, surfers say that such waves can’t be paddled into, since you can’t paddle fast enough. The prelude to the ride is a smooth initial run on a very round unbroken wave, gathering enormous energy before it explodes in epic fury. The master of this art is Laird Hamilton.

Gerry Lopez has gone beyond the poet into extraordinary eloquence. In the two epics of Homer Odysseus as well survived terrifying wipeouts. Lopez is homeric describing “the sheer terror” of his wipeouts, like his catastrophic wipeout at G-Land in Indonesia. Caught "inside", a “rogue set” of monstrous waves steamed down on him mercilessly “as the surge got a grip on my legs”. Just before the first of several colossal walls of churning white water from “rogue waves” collided with him, he “groaned in helplessness”:

My mind was ticking like time bomb as I ran through my options. I found no solace in any of them; there didn’t seem to be any escape from this imminent pounding. Cold fear washed through me as I realized that I couldn’t even abandon ship and dive underwater. It was just deep enough that this much whitewater was going to tumble me for a long distance down the point, into all the pain and suffering that lay that way. My mind was on the edge of panic… Closer and closer it came and I still didn’t have a plan.The homeric quality of this chapter on G-Land is a fresh sensation as if the reader were there as well in the turbulent “wine dark sea”. This epic wipeout at a break called the Launch Pad put great terror in his warrior heart: “It was like the maelstrom of the ancient mariners, the whirlpool of death from which no one escapes.” Compare this classic wipeout 3,000 years ago with “groaning” Odysseus:Odysseus was left in perplexity and distress, and once more took counsel with his indomitable soul... This inward debate was cut short by a tremendous wave which swept him forward to the rugged shore, where he would have been flayed and all his bones broken had not the bright-eyed goddess Athene put it into his head to dash in and lay hold of a rock with both hands. He clung there groaning while the great wave marched by. But no sooner had he escaped its fury than it struck him once more with the full force of its backward rush and flung him far out to sea. (The Odyssey, chapter 5, tr. E.V. Rieu)Gerry Lopez didn’t have a plan for escaping annihilation at the Launch Pad, and that indeed is the secret of his superiority as a survivor like Odysseus lamenting : “Let this calamity come – it only makes one more.” Lopez sums up: “Total panic was just around the corner, but somehow I didn’t go there.” Reading about Gerry Lopez with Gerry Lopez as narrator is a sublime experience. The sheer grace of his surfing permeates the other arts he practices, permeates his life. This is the meaning and purpose of Art: permeate society with the soul-saving creativity of the artist, whether a surfer, painter, poet or musician. The ancient Greeks knew this , and Art was the guiding principle of their societies.His saga growing up in Hawaii is breath-taking. The North Shore on Oahu was his playground. He writes much about the Japanese-American side of his mother, but almost nothing about his Spanish father, who was also a writer. Some of the greatest living surfers are his intimate friends. Up to his high school graduation in 1966, surfing was not a high priority for him, although he had been surfing for many years. “I now discovered that it was really all I wanted to do.” The graceful, harmonious and relaxed style he displays while surfing extremely dangerous waves is the grace of the Ocean itself. He knows the fine details of calamity, its feet and inches of proximity: “Yet, 20 feet behind a guy who’s having it easy, another surfer might be on the edge of terror, skirting disaster by only inches.”

Gerry Lopez displays keen knowledge of the rhythms of the earth; the tides; the winds; the cycles of the moon; the seasons; the geography of Indonesia, Bali, his native Hawaii and many other parts of the world that he visited with his surfing buddies: “We timed all our trips to coincide with the new and full moon tides.” Once upon a time societies were governed by such people… oh, that’s another story that Homer told better. Such direct knowledge from nature emanates spiritual power that shines into the odds-and-ends of daily life. Unfortunately, society does not benefit from this knowledge, just as modern Greece does not benefit from Homer.

‘Twere long to tell, and sad to trace,

Each step from splendor to disgrace.

– Byron

Lopez lives with Catastrophe as a next-door neighbor, and learned how to deal with it. Becoming an adept of surfing and yoga, he nurtures a calm, centered and relaxed state of mind as in tai chi. This quality emanates from the photo of him surfing Money Trees in Indonesia, where he displays a swordsman’s precision, the surfboard’s rail cutting the vertical wall of green water like a tai chi sword cutting bamboo.

Lopez finishes some chapters with a concise poetic reflection on the lessons he has learned on his path of “surf realization.” This is a profound expression for the full potential surfing offers us, not only the physical aspect of riding waves, but the spiritual aspect which just as well as not can lead to Enlightenment. These concise reflections emanate the art of the Aphorism. Surviving the horror of the catastrophic wipeout at the Launch Pad, he emerged from the agony of annihilation and summed it up in an aphorism: “If one believes that the truth lies within, faith dictates that it will reveal itself when it is most needed.”

In the chapter “The Mother of all Pipeline Swells” Lopez writes of an uncommon ground swell in September during three days at Pipeline. It was months before all the non-Hawaiian surfers swarmed to the North Shore from all parts of the world for the big winter surf: “It was a local boys only swell.” His description is more revealing than anything I have read about the physical realities of not only surfing Pipeline on a big day, but the ordeal of paddling out and wiping out as well: “This is not a situation to take lightly. The chilling specter of death haunts the Pipeline reef. More surfers have been killed there than at any other surf spot.” The trial of the first day made it almost impossible to paddle out even for these amazing athletes. Lopez paddled and paddled through enormous surf, exhausting himself as the sets rolled in mercilessly without a lull. “All that paddling had gained me precisely nothing... Some other guys had been trying to get out for more than an hour and hadn’t been able to.” Finally, after a courageous struggle he was able to paddle out to the lineup and catch “his” wave. Now he was inside that enchanting tunnel of water, and “the roaring sounds of the waves crashing were suddenly silent... I was one with the universe.”

Garrett McNamara surfing a 100 ft. wave in

Nazaré, Portugal (January 2013)Gerry Lopez, like other surfers who have written or co-written books, fills many pages with accounts of extraordinary men and women who have devoted their lives to the ocean. Again I am reminded of Homer, who sang of extraordinary men and women, like Achilles in his tent on the battlefield of Troy, playing his lyre and singing of “the glorious doings of men.” Some of the surfers mentioned by Lopez are well-known. Others are less known, like Garret McNamara (above), mentioned only once. Five years after the publication of Surf is Where You Find It, Garret McNamara rode the biggest wave ever ridden, a monster reportedly 100 feet high in Portugal. The video of this deed that became famous on the internet shows a tiny figure perched on a mountaintop that is a wave, making the biggest drop in surfing history. Another extraordinary man he described is “Dr. Surf”, Dorian Paskowitz from Israel, still surfing in his eighties.

Laird Hamilton surfing Jaws

National Geographic Nov. 1998

signed by Laird Hamlton and auctioned on E-BayThe chapter entitled ”A Good Day to Die” is about Gerry Lopez mastering his fear of Jaws and surfing it for the first time, with Laird Hamilton and his comrades as mentors. (Although he quotes this from the movie “Little Big Man”, the historical source is Crazy Horse’s speech to his warriors before entering battle: “Today is a good day to die.” ) Spending much of his childhood on Maui, Lopez once considered padling out with his brother at Jaws in the 1970s, before it was even known by that name or surfed. The waves appeared smaller than they really were from the top of the cliff, “where we watched in open-mouthed awe.” Several times he and his brother tried to get up the nerve to paddle out: “After climbing down the steep trail to the rocky shore below, however, we changed our minds. From the rocks near sea level the place was utterly forbidding.” (Jeff Clark had a similar experience discovering Mavericks in California, but paddled out and surfed it for 15 years alone before it was in turn discovered by other big wave surfers.) Twenty years would pass, and the innovations of the jet ski and foot straps made it possible to surf what Lopez calls “the heaviest break I had ever seen.” Out in very deep water, when he received the question “Are you ready?” from Dave Kalama, the jet-ski driver, he answered, “Why not?” In the pioneering phase of surfing Jaws, Laird Hamilton and his friends “became so good that everyone of them was capable of riding several waves in a set without getting his hair wet.”

Gerry Lopez leads the reader like a mountain guide into amazing realms that we others can only dream of. His skill in describing epic ocean scenes is smoothly transformed into the unique adventure of “mountain surfing” in British Columbia, the “blue bird bliss” in this “snow-surfing paradise.” His literary images are so crystal clear that the most sublime, inaccessible moments are conveyed like a handshake to the reader. Like life, mountain surfing is “a dangerous and potentially deadly affair.” The book reveals a detailed knowledge of the anatomy of fear, its tiniest details and fractions of seconds during wipeouts and avalanches.

Collaborating with elite European snowboarders on a film project, Lopez and his surfing friends agreed to introduce them to surfing on the North Shore, and the Europeans would introduce the Hawaiians to extreme snow-boarding in the Alps. The Hawaiians were gracious hosts. When the waves on the North Shore proved to be so terrifying to the snowboarders that they wouldn’t even get out of the car, the Hawaiians took them to the West Shore. There the waves were smaller, but still big. Even here the Europeans were too frightened to give it a try.

When it came time for snow-boarding in the Alps, the Europeans decided that they wanted to take revenge on the Hawaiians for having lost face. And so they deviously planned to scare the wits out of their guests high on a steep snow-covered crag in the Alps. Although the Hawaiians learned later that there was a much safer spot to land the helicopter, they were obliged to exit the machine as its propellors were still spinning, with only one landing ski resting on the extremely narrow ridge. Getting out with their gear, Lopez and his friend Darrick Doerner were petrified with fear looking down both sides of the narrow ridge at an abysmal drop that meant certain death for anyone who fell.

Although they as well were elite snow-boarders, they had never experienced anything like this. Lopez tried to give his friend moral support, and then summoning his courage, he made the plunge and snow-boarded down to the safe ledge where the Europeans waited, and where the helicopter normally landed. Poor Darrick! Although he is a legendary big wave surfer known for extraordinary courage, he was so terrified that he was obliged to crawl on his hands and knees off the ledge to safety as the Europeans laughed at him. He never forgave them this sadistic trick.

The provincial story of Oahu’s North Shore in the early 1970s, when Honolulu was called “town”, is told with Lopez usual vividness and skill. He evokes a “feeling” of his youth that is lost forever, like the “feeling” of coastal southern California in the 1950s and 60s. “It was a sleepy, quiet place where the roosters crowed at first light and the roads were always empty.” I too grew up in such a place, and sweet is the melancholy evoking it. Hobnobbing with locals, many of whom were skilled surfers, Lopez writes that “we would talk story a bit.” Here is the unassuming modern link to the epic tradition of Homer, who emanated centuries of bards before him who “would talk story a bit” about extraordinary men and exploits. Just as the natural order of surfing Sunset, Pipeline, Makaha or Waimea reveals gradations of mastery, so is the natural order of writing. Lopez had direct access to the ancient story-telling tradition of Hawaii that remains alive throughout generations: “Nonaka…used to come out once and a while and talk to us about the old days.” In his book, Lopez does just that and brings us up to date with modern times.

Despite its literary power, Surf is Where You Find It will likely not reach the wider reading public which it deserves. One need not be a surfer to enjoy it. I go back to it again and again, re-reading in a manner that is rare for me when I read prose normally. I am bewitched. Lopez’ mastery of English allows him to span the (at times mindless) jargon of surfers on the most local level (as was my experience surfing in southern California), and the eloquence of ancient warrior poets like Horace. From the world for which “bitchin” and “stoked” is normal language, to the splendid poetic prose of the last chapter “Jungle Love,” Gerry Lopez has given an in-depth narrative of surfing. He knows the ocean in a sensual way as a man knows a woman.

The oceanic disasters at G-Land in Indonesia which he previously described at great length, are surpassed by the disasters of this last chapter on G-Land, where the rage and terror of the ocean was even more intense this time around. Gerry broke his “Lopez Rule #4”: “Never, ever, take the first wave of set.” He paid dearly for breaking this rule, getting “caught inside” and surviving by a hair the calamities of the three remaining monster waves of the set. He did not dare look at the first wave he was obliged to get over. It was so terrifying that he paddled toward it with his head down. “If there was a time to call for Mama, this was it.” His strategy required absolute precision to succeed: “It had to be perfect or I was done.” One can compare the precision needed by Odysseus to escape the Cyclops’ cave with all his men. They had no choices. Survival was the only option for both. “No choosing, no deliberating, just do it.”

In tai chi, acting when having no choice is called wu wei, “acting without striving,” that is – being one with the Way, or as Lopez calls it, Truth. “The Truth is when things are as they are.” The final lesson is that of a sage in tune with the natural energy of the earth, which allowed him to overcome Fear: “By abandoning the notion of choice, I was in a place where my innate abilities and intrinsic wisdom were able to rise above my fears and expectations.”

Big Surf, Deep Dives and the Islands

My Life in the Ocean

Ricky Grigg

Editition Limited, Honolulu 1998

Unique among the many books on surfing history that I have read is Ricky Grigg’s Big Surf, Deep Dives and the Islands: My Life in the Ocean. Following the life story of one of the legendary big wave surfers who were models of manhood for me growing up in California, I am deeply moved by this poetic tribute to the Ocean, friends and life itself. The many photographs of big waves, ocean depths beyond 1,000 feet, pioneer surfers and the following generations of surfing champions are a vivid compliment to the eloquence of this extraordinary man, scientist, big wave surfer and philosopher. After purchasing this book directly from the author, I didn’t begin reading it immedately. After thumbing through it I sensed that it would require “the right moment” to begin reading it, considering the in-depth treatment Grigg gives not only surfing, but oceanography and philosophy. The latter endeavor historically attempts to confront the illusive concept “wisdom”, with varying results. In Grigg’s case it is the real thing. He has two distinct personas: scientist and big wave surfer. Richard/ Ricky Grigg’s love affair with the Pacific Ocean began as a small boy growing up in Santa Monica on the coast of southern California. His life was shaped by the Ocean in every way –emotionally, athletically, professionally, and spritually:

Through surfing, and later in my life by studying the sea, the ocean became a consummate teacher. It shaped my body and mind, my personality, my philosophy, my view of life, my persona. To me, the ocean represents truth… To seek the truth is to search for the essence of life… In the ocean, the truth is all that there is.

|

|

The Tongva people of coastal southern California had an ancient tradition of paddling plank canoes to and from the offshore islands. The most trafficked stretch was between Pimu (Santa Catalina Island) and Swa’anga, located on Palos Verdes peninsula, near the port of San Pedro, the largest and most populous Tongva village. (This village was seen by Cabrillo when he sailed past in 1542.) This maritime tradition died out, but was unknowingly revived by hardy surfers on paddleboards who established a short-lived tradition of a 33-mile open-ocean race between Santa Catalina and Manhattan Beach between 1955 and 1960. The first race in 1955 was on a foggy day with low visibility. One contestant paddled 11 miles too far in the fog. First to shore, Tommy Zahn was disqualified because he missed Manhattan Beach, the finish line. The 17-year-old future big wave surfer and oceanographer Ricky Grigg was declared the winner before a crowd of 100,000 people. In September 1995, descendants of the Tongva revived their maritime tradition and paddled the first ti’at constructed in two hundred years from Two Harbors on Santa Catalina to the port of Avalon. This link between Californian surfers and Native Californian watermen evokes that between modern Hawaiian and Tahitian surfers and their Polynesian predecessors.

The Californian Ricky Grigg has after decades become the Hawaiian Ricky Grigg, the 75-year-old surfing patriarch who has been intimately involved with the tragedies and triumphs of surfing and diving comrades on Oahu and the other islands. Chapter 20 of his book, the last, entitled “Life at the End of the Tunnel” begins opposite a full-page, blurry, black and white photo of the young Ricky Grigg riding probably one of the biggest waves of his life, a frightening “tunnel” at what could be Waimea. Looking at this photo I am reminded how stunned I was as a fourteen-year-old subscriber of Surfer Magazine looking in awe at such photos of bold-hearted surfers like Grigg, Noll, Dora, Curren, Pomar and others. (left: Ricky Grigg on the cover of Surfer Magazine) Almost fifty years later, I am still stunned. My admiration remains intact. I understand why surfers were considered as possibilities for the first men to be launched into space – for their calm, steady, unflinching courage and impeccable judgment in the face of danger. An added attribute in the case of Ricky Grigg is his deep scientific and philosophic knowledge of the Ocean, which he sees as the embodiment of truth.

The Californian Ricky Grigg has after decades become the Hawaiian Ricky Grigg, the 75-year-old surfing patriarch who has been intimately involved with the tragedies and triumphs of surfing and diving comrades on Oahu and the other islands. Chapter 20 of his book, the last, entitled “Life at the End of the Tunnel” begins opposite a full-page, blurry, black and white photo of the young Ricky Grigg riding probably one of the biggest waves of his life, a frightening “tunnel” at what could be Waimea. Looking at this photo I am reminded how stunned I was as a fourteen-year-old subscriber of Surfer Magazine looking in awe at such photos of bold-hearted surfers like Grigg, Noll, Dora, Curren, Pomar and others. (left: Ricky Grigg on the cover of Surfer Magazine) Almost fifty years later, I am still stunned. My admiration remains intact. I understand why surfers were considered as possibilities for the first men to be launched into space – for their calm, steady, unflinching courage and impeccable judgment in the face of danger. An added attribute in the case of Ricky Grigg is his deep scientific and philosophic knowledge of the Ocean, which he sees as the embodiment of truth.

The scientist Richard Grigg is quite a contrast to the surfer Ricky Grigg, and provides interesting information on oceanography in his book. In very clear terms he describes how the Hawaiian islands are gradually “drowning” in the Pacific as the tectonic plate carries them northwest over the volcanic "hot spot" which formed each island one after the other over tens of millions of years, and then deep into the trench off Kamchatka. Evidence of this "drowning" comes from the conclusions Grigg reached about the Darwin Point, the latitude where the islands begin to "drown". It took him five years to prove this hypothesis. The fossilized coral reefs which he saw and photographed at 1,200 feet are the proof, since coral grows only at much shallower depths. Now I know that coral atolls are round because they were formed on the rims of drowning extinct volcanoes. From the crest of a huge Waimea wave as he makes the plunge "over the edge", to 1,200 feet down on the ocean floor, Richard/Ricky Grigg has a knowledge of the Ocean like few other people.

Other surfers have written books (see below) but I have not yet encountered a writer/surfer with the philosophical depth and scope of Grigg. As a scientist and a surfer, he is preoccupied with distinguishing fact from fiction. Understanding reality is the main focus of taoist sages, and it has been the focus of Ricky Grigg his whole life: “The truth for me must be based on more than ideas – there must be some solid evidence. This rule has been vital to my survival riding big waves. It is also vital to conducting good science.” I surmise that he nonetheless acknowledges “soul” and “spirit” as truths, despite the fact that there is no “solid evidence” that would satisfy the demands of a not-so-spiritual scientist like, say, Richard Dawkins. Despite the lack of scientific “solid evidence”, I am convinced by his book that Richard Grigg, as opposed to Richard Dawkins, believes in Spirit and Soul.

Death is another fact that science cannot explain and which is the subject of an entire chapter in Grigg’s book. He regards Death as not only a possibility surfing big waves and diving to the limits of what humans can endure, but an inevitability for us all, whether one dies in a wipeout on a big wave, as did Mark Foo, or in one’s bed. Foo was one of several of Grigg’s friends and colleagues who perished in the Ocean. Foo’s body was recovered, but the bodies of Eddie Aikau and Jose Angel were never found. He writes: “There have been many other stories like Jose [Angel]’s over the years of lost black coral divers: Danson Nakaima, Larry Windley, Tim Lebalaster, and Tim’s son Beau, to mention a few.” Larry Windley, partially paralyzed with the bends, “sailed out to sea in a 15-foot catamaran, never to be seen again.” On April 5, 1951 at Malibu, surfer/poet Nick Gabalon rode an 8-foot wave straight into the pilings of the pier and was killed, six days after writing a poem called “Lost Lives”. Grigg’s recollection is hair-raising:

Three days later his body was spotted floating offshore. I remember paddling out, not knowing exactly why – probably to be sure it was Nick. After paddling 400 or 500 yards out, I could see his body floating face-down A seagull sat perched on his bloated back, which had turned white after three days’ immersion in the ocean. [Gabalon was African American] The bird was pecking at his flesh. I remember thinking then how fleeting life is, how it can be snatched away in an instant. How insignificant we all are. Death contradicts human importance. It shatters the ego. The sight was devastating to me, but somehow it helped me grow stronger.

He quotes a magnificent verse by Emily Dickinson:

Because I could not stop for Death,

He kindly stopped for me;

The carriage held but just ourselves

and immortality.

The Poet touches on realities which the scientist passes by because he can find no “solid evidence” for them. The fact that the scientist Richard Grigg cites Dickinson, Shakespeare and other poets reveals a kinship with Art, whereas the mighty Isaac Newton thought Art not to be worth his consideration. It is likely that Grigg’s profound closeness to the Ocean gives his scientific scrutiny an artistic bent. The possible union of Art and science has been a major theme of my writing, as it was for Goethe, but I do not believe that it will ever be realized.

Purchase this book from the author here

Another legendary surfer from California who captivated me as a teenager scrutinizing Surfer Magazine is Mike Doyle. His book Morning Glass, co-authored by Steve Sorensen, is great reading, and reveals quite a different personality than Ricky Grigg above. Grigg, who is seven years older, was a sort of mentor to the young Doyle when he was a lifeguard at Manhattan Beach and when he first began surfing the big waves of Oahu’s north shore. Mike Doyle, like Greg Noll in Da Bull: Life Over the Edge, tells his story with ribald humor, and it took only a few pages before I broke out laughing. But he went too far at times.

The story of his first wave as a boy at Manhattan Beach reveals a quirky accident that, although marking him for the rest of his life, is pure comedy. The humor comes from recalling at times painful moments in his youth, whether crushing his testicle after bailing out of his first wave, or being ridiculed and mobbed: “No matter where I was, at school or at the beach, I just didn’t fit in.” This led to Doyle longing for “camaraderie,” which he indeed found. And now he was making newcomers feel like fools, mocking them with his comrades when they came down the steps at Malibu.

Another legendary surfer from California who captivated me as a teenager scrutinizing Surfer Magazine is Mike Doyle. His book Morning Glass, co-authored by Steve Sorensen, is great reading, and reveals quite a different personality than Ricky Grigg above. Grigg, who is seven years older, was a sort of mentor to the young Doyle when he was a lifeguard at Manhattan Beach and when he first began surfing the big waves of Oahu’s north shore. Mike Doyle, like Greg Noll in Da Bull: Life Over the Edge, tells his story with ribald humor, and it took only a few pages before I broke out laughing. But he went too far at times.

The story of his first wave as a boy at Manhattan Beach reveals a quirky accident that, although marking him for the rest of his life, is pure comedy. The humor comes from recalling at times painful moments in his youth, whether crushing his testicle after bailing out of his first wave, or being ridiculed and mobbed: “No matter where I was, at school or at the beach, I just didn’t fit in.” This led to Doyle longing for “camaraderie,” which he indeed found. And now he was making newcomers feel like fools, mocking them with his comrades when they came down the steps at Malibu.

Reading about the demented pranks by some of these comrades, not only in Doyle’s book but in other surfing chronicles, reminds me all too well of the hooligans I grew up with in southern California. How could I fit in with young men who were either sexually depraved enough to drop their pants in public, cheerily displaying their anus or erect penis, or applaud these demented pranks as does Doyle: “I thought it was beautiful – a kind of performance art that made a mockery of people’s fear of nudity… He was years ahead of his time.” As for me, solitude is preferable to such “camaraderie”. Good character is simply not on the radar of these “performance artists.” However, receiving his induction notice from the US military Doyle’s reaction was identical to mine: “As far as I was concerned, the military was the enemy.”

Doyle’s first trip to Hawaii liberates the reader (as it liberated him) from the pettiness of southern California (despite its proximity to the grandeur of the Pacific Ocean). As in other surfing chronicles, the reader is feasted on the epic poem of the North Shore of Oahu. As with Homer’s epic, I have read and re-read this Hawaiian saga many times from many viewpoints. Despite the profound differences of writing style between Mike Doyle and Ricky Grigg (above), this epic sensation emerges into the same awe in both cases. His first day surfing the North Shore was at Pipeline, although he was unaware of this fact when he paddled out alone as a gullible 18-year old and made his first wave. Waiting onshore were his older mentors: Ricky Grigg, Buzzy Trent and Peter Cole: “They really took me under their wing that day."

Back in southern California after a 5-month adventure in Hawaii, the young Doyle again confronted the routine depravity of the City of Angels. As a lifeguard for Los Angeles County, there were few rescues in summer when the surf is not so big. The lifeguards got bored and amused themselves in various ways. Doyle refused to be a part of a homosexual orgy in one of the lifeguard towers. (It later became a courtroom scandal in which they were publicly humilated and fired.) This type of “camaraderie” was perhaps more usual than one can imagine, judging from the next account Doyle wrote of.

Doyle’s first trip to Hawaii liberates the reader (as it liberated him) from the pettiness of southern California (despite its proximity to the grandeur of the Pacific Ocean). As in other surfing chronicles, the reader is feasted on the epic poem of the North Shore of Oahu. As with Homer’s epic, I have read and re-read this Hawaiian saga many times from many viewpoints. Despite the profound differences of writing style between Mike Doyle and Ricky Grigg (above), this epic sensation emerges into the same awe in both cases. His first day surfing the North Shore was at Pipeline, although he was unaware of this fact when he paddled out alone as a gullible 18-year old and made his first wave. Waiting onshore were his older mentors: Ricky Grigg, Buzzy Trent and Peter Cole: “They really took me under their wing that day."

Back in southern California after a 5-month adventure in Hawaii, the young Doyle again confronted the routine depravity of the City of Angels. As a lifeguard for Los Angeles County, there were few rescues in summer when the surf is not so big. The lifeguards got bored and amused themselves in various ways. Doyle refused to be a part of a homosexual orgy in one of the lifeguard towers. (It later became a courtroom scandal in which they were publicly humilated and fired.) This type of “camaraderie” was perhaps more usual than one can imagine, judging from the next account Doyle wrote of.

Rincon, near the small town of Carpinteria (“the carpinter’s shop”) is one of the best surfing spots in California. But its splendor offers a serene oceanic environment to non-surfers as well, a veritable sacred place – to the Chumash people first and foremost. Doyle relates how he enrolled in a junior college at nearby Santa Barbara. He rented a house in Summerland “with four other guys” and the landlord lived undoubtedly to regret it (especially after their boisterous party with 200 people). Doyle rejoiced at being so near Rincon for surfing, which before had meant a long drive for him. It is odd however that the writer Doyle did not leave his reader with the splendor of Rincon as the focal point of his memories living nearby. Descending the long wooden stairway down the bushy cliff to the beach, feeling the cool sand under one’s bare feet, the weight of the surfboard under one’s arm, the glassy waves rolling through the kelp beds and peeling off the point, the sun rising over the Ventura rivermouth – this is not the main impression with which he leaves the reader about his memories near Syukhtun (the Chumash town occupying the site of Santa Barbara for 8,000 years.)

The splendid point at Rincon was not the main focus of these memories, but (believe it or not) the anus of one of his deranged latent-homosexual surfing buddies whose delight was to pull down his pants in public and expose not only his butt, but the interior of his anus. A writer might possibly mention such a memory in passing as a sort of psychologist observing the pathological behavior of a young hooligan in need of professional help, who had previously that night trashed the house in Summerland in a drunken rage. But to celebrate this type of behavior and leave this in the mind of the unfortunate reader instead of the splendor of Rincon is a strange priority. Poetic reverence for the Ocean as expressed so eloquently by Ricky Grigg in his book above, comes to a tragic halt here, despite the poetic title Morning Glass.

Rincon

Doyle's humor again emerges when he relates a promotional tour for Catalina beach wear which took him to New York and other eastern cities and finally Galveston, Texas. His job was to demonstrate surfing in his jim-dandy Catalina surfing trunks to the large crowd gathered on the beach. He walked about 150 yards into the Gulf of Mexico and the depth was still only three or four feet. The water was ”the color of chocolate milk” and flat. The legendary big wave surfer finally paddled into a wave as his brand new Catalina Big-Wave Rider's trunks ”ripped from the crotch, through the seat, clear around to the waistband.” Nonetheless he jubilantly rose to his feet on ”a cleanly shaped twelve-inch wave, with my bare ass hanging out,” showing the large crowd of Texans the fine art of surfing. As in Shaun Tomson's autobiographical book below, as well as in other surfing narratives, the subject of ”the clothing market” is given very much attention. In most cases it is a rather boring digression from their noble art, and I feel like I must hurry past these narratives like thumbing through glossy ads in a magazine looking for text with substance.

Doyle's humor again emerges when he relates a promotional tour for Catalina beach wear which took him to New York and other eastern cities and finally Galveston, Texas. His job was to demonstrate surfing in his jim-dandy Catalina surfing trunks to the large crowd gathered on the beach. He walked about 150 yards into the Gulf of Mexico and the depth was still only three or four feet. The water was ”the color of chocolate milk” and flat. The legendary big wave surfer finally paddled into a wave as his brand new Catalina Big-Wave Rider's trunks ”ripped from the crotch, through the seat, clear around to the waistband.” Nonetheless he jubilantly rose to his feet on ”a cleanly shaped twelve-inch wave, with my bare ass hanging out,” showing the large crowd of Texans the fine art of surfing. As in Shaun Tomson's autobiographical book below, as well as in other surfing narratives, the subject of ”the clothing market” is given very much attention. In most cases it is a rather boring digression from their noble art, and I feel like I must hurry past these narratives like thumbing through glossy ads in a magazine looking for text with substance.

Newly married and living in Leucadia, California, Doyle bought a run-down house which he repaired, especially pleased with the dark rich soil which was perfect for a vegetable garden. Loving liberty, he wished to grow as much food as possible for his needs, and be dependent on society as little as possible. Unfortunately, his bride did not share this dream and they separated. After another brief marriage and other brief relationships, Doyle met a female New Age guru in La Jolla who was very famous and who impressed him with her skill at public speaking. He began still another brief relationship with her and helped her in marketing her image and tapes of her seminars. One tape on “relationships” was Doyle’s idea (despite his lack of competence in this area) and he outlined the thoughts in it, which he admitted was “ironic”, adding: “I’m the first to admit I’ve never figured out relationships myself and have only had succeess with them on a temporary basis. But then its possible that nobody ever does any better than that.” It is a shame that he would deceive himself to this degree, especially when he had friends committed to wives and children, and when there are plenty of loving couples who live together their entire lives. One can be a skillful speaker and have nothing of value to say. It is called hypocrisy.

Mike Doyle belongs to a long tradition of highly skilled watermen in California that is part of a coastal tradition of several generations. Most of these ultra-athletes grew up on the coast and were trained by fathers, older brothers and friends. The watermen of California leave behind epic stories of courageous and intelligent confrontations with the Pacific Ocean. They were and are thoroughly at ease in the Ocean, even with a killer whale passing directly under one’s board in 15 feet of water, as happened to Allen “Dempsey” Holder at the Tijuana Sloughs in the early 1940s. Dempsey remained as quiet as the black and white spots on the huge killer whale gliding beneath him, when Bob Simmons let out a loud curse ‒ two different approaches. They were riding some of the biggest most dangerous waves ever surfed. The intense freedom which has marked Doyle's adventurous life is truly admirable in our civilization of slaves

The most memorable moments of surfing history have not been captured on film, like Miki Dora’s 0.7 km ride on a wave at Jeffreys Bay described below, or Greg Noll’s legendary wipeout on a record big wave at close-out Makaha. In the same respect, the highlight of Mike Doyle’s surfing career was on the island of Kauai at Hanalei Bay – far from hectic competitions and video cameras. I was captured by his narration of that splendid day surfing with his friend Joey Cabell and a few other surfers who had discovered this virtually unknown surfing spot. In spite of our high-tech society such moments are best preserved in books, as it has been for thousands of years of history.

The two sides of Doyle – “contest junkie” and “soul surfer” – are very well delineated in his book. He began to feel that something was warped with competitions: “My reputation was influencing the judges, and sometimes it was embarassing for me to see that I had placed higher than somebody who had outperformed me.” Even though he was a highly acclaimed champion surfer, he did not take this aspect of surfing seriously. Mike Doyle is an artist who regards surfing as an art, not a sport. Competing in art is meaningless. Trophies and prizes are illusions: “Surf stardom interferes with your development as a human being.” Of much more value to Doyle are the secret moments like that day at Hanalei Bay.

After terminating his career as a professional surfer, he proceeded with his ingenuity and entrepreneur skills to make new inovations in the areas that interested him. He is the first to design and produce a single ski based on his knowledge of surfboard design and a gut-feeling that double skis were awkward on a downhill slope, since they were originally conceived for cross-country treks, not as sport equipment. Although his well-tested product never went into production, it was the precursor of the snowboard. Mike Doyle is also a painter and writes that art was his favorite subject in school. He has his studio and gallery in Cabo San Lucas where he lives and runs a surfing school.

All for a Few Perfect Waves

The Audacious Life and Legend

of Rebel Surfer Miki Dora

David Rensin

HarperCollins, NY, 2008

However, unlike the disillusionment I experienced reading the Willem de Kooning biography below, David Rensin’s Dora biography does not cause disillusionment, for Dora’s reputation as a thief and con-man was equally as well-known as his reputation as a master surfer to those of us who have followed his audacious life. The present biography flows along nicely through the commentaries of people who knew Dora. But the flow is at times interrupted by Rensin’s own personal style of journalistic writing. (The English language has now been blessed with a brand new word coined by Rensin: “sentimelancholia”.) Although the “I” who is the author of a biography can enhance the narrative with his or her own background, the purpose still remains to provide a clear window through which the life story appears in highest resolution. In the first few pages, the unique Miki Dora is compared to a tediously long list of celebrities: Elvis Presley, James Dean, Marlon Brando, John Cassavetes, Muhammed Ali, Flying Wallenda, Cary Grant, Jack Kerouac, Bob Dylan, Sid Vicious, Andy Warhol, etc. Is this comparison needed? Is any comparison needed?

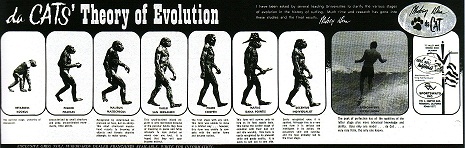

Admitting that Dora “notoriously disliked ‘surf music’”, Rensin nonetheless insisted on quoting a long passage from a Beach Boys’ song to dubiously illustrate a point. Having grown up in southern California, I feel that the Beach Boys were not really connected to the intrinsic mystery of the Pacific Ocean and its coasts, as was Dora. I had to keep it a secret that I never liked their music. They represented the commercialization which Dora detested. If indeed I were obliged to make a comparison, it would not be with movie and rock stars, but with another legendary alumnus of Hollywood High School, Everret Ruess, who disappeared in the year of Dora’s birth, 1934. The former lived an uncompromising life committed to the most audacious personal freedom, like Dora, before disappearing into a Utah desert at the age of 20. (Unlike Dora, Everett Ruess displayed the integrity and good character of a sage.) Following the life of Miki Dora over the decades I have encountered an astonishing and unique homo erectus, as seen in his classic surfboard ad (below) showing the evolution of surfing as human evolution, from primordial apes to Dora riding a Malibu wave – the “aquatic ape”. Despite the wit in this ad, supposedly conceived by his friend Darryl Stolper, it also reveals Dora with a pathological ego - as the culmination of human and surfing evolution. It also reveals a latent fascist who was extremely cruel to his younger friend and protegé Johnny Fain (“Pygmio Phainas”, the next to the lowest rung in Dora’s theory of evolution), who adored Dora like an older brother. Despite beating Dora in one Malibu competition, and Greg Noll calling him a “great surfer”, Fain (“Pygmio Phainas”) was “uncoordinated”, with “little ability” in Dora’s surfboard ad. Fain was humiliated and crushed: “He (Dora) withdrew his affection from me entirely. It broke my heart and hurt me very badly.”

A theme on this commentary page (see below) has been good character, and how rare it is in our culture. Miki Dora, Greg Noll and their surfing companions regarded good character as something a bit stupid, something that they felt their duty to avoid in order to be a “rebel”. Noll said, “I have difficulty making people understand this,” that is, that he and his companions regarded bad character as desirable, and good character as undesirable. That is the Dora legend: good surfing combined with bad character. There are people from whom you should not buy a used car, and others from whom you should not buy a used surfboard. According to surfer Mickey Muñoz, Dora’s attitude, after mixing graham cracker crumbs in the resin of a surfboard he was repairing, was, “Do it half-ass, get it done, get the money, and run.” Miki Dora’s teacher in good surfing and bad character was his step-father Gard Chapin. He could have learned more good character from his Hungarian father, Miklos Dora, Sr., as he himself admitted: “One father showed me how to atone for indiscretions and the other demonstrated how to commit them.” (Unfortunately, Dora’s father, a military man, had the extreme bad judgement of placing his little son in a military academy - a good way to foster hatred of all authority in a boy.)

A theme on this commentary page (see below) has been good character, and how rare it is in our culture. Miki Dora, Greg Noll and their surfing companions regarded good character as something a bit stupid, something that they felt their duty to avoid in order to be a “rebel”. Noll said, “I have difficulty making people understand this,” that is, that he and his companions regarded bad character as desirable, and good character as undesirable. That is the Dora legend: good surfing combined with bad character. There are people from whom you should not buy a used car, and others from whom you should not buy a used surfboard. According to surfer Mickey Muñoz, Dora’s attitude, after mixing graham cracker crumbs in the resin of a surfboard he was repairing, was, “Do it half-ass, get it done, get the money, and run.” Miki Dora’s teacher in good surfing and bad character was his step-father Gard Chapin. He could have learned more good character from his Hungarian father, Miklos Dora, Sr., as he himself admitted: “One father showed me how to atone for indiscretions and the other demonstrated how to commit them.” (Unfortunately, Dora’s father, a military man, had the extreme bad judgement of placing his little son in a military academy - a good way to foster hatred of all authority in a boy.)

There is an irony about the pop Malibu fairy-tale not touched on by Rensin. Although he briefly mentions that the name is Chumash in origin, Rensin no longer is concerned with this deeper, more meaningful Malibu past, much much older than than the golden age of Miki Dora and Bob Simmons having the perfect waves and the beach almost uniquely for themselves. Dora’s classic complaint over the “imbeciles” who took over his sacred place can be made by the modern Chumash people with much more authority. Dora’s grievance is nothing by comparison. He too becomes one of the “imbeciles” who invaded and usurped a sacred place. Dora’s grievance is well-known. The Chumash grievance is unknown. Those people today swarming on the beaches and the waves of Malibu are able to do so only because of the genocide inflicted on the Chumash people.

In his youth Dora’s greed for waves at Malibu was such that he became infamous for consciously trying to injure surfers who were on “his” wave by kicking out with his long board and aiming at the head of his enemy. (At left Dora pushes Johnny Fain off the wave) One of the few to have surfed Malibu in near solitude, he could not accept that those idyllic days were gone for ever. After the invasion of the “kooks”, the “king of Malibu” was not all that kingly. One average surfer, a Mexican-American named Oscar, took off on the same Malibu wave as Dora. Enraged, Dora rammed Oscar and destroyed both of their rides. Later, as Oscar sat peacefully on the beach with his family, Dora came out of the water and very belligerently demanded that Oscar (who was younger, shorter and lighter) get off “his beach” or else Dora would “beat the shit” out of him. As Oscar stood up to meet the challenge, Dora attacked him, not knowing that Oscar was a Golden Gloves boxer. After warding off Dora’s wild swings, Oscar punched “the king of Malibu” in the face and knocked him unconscious in plain view of his adoring fans. Dora was so disgraced that he didn’t show his face at Malibu for five days. Not having the humility to accept this defeat, Dora later sued Oscar for assault and was awarded $131.90 in damages, an example of the American way of punishing the victim and rewarding his aggressor.

In his youth Dora’s greed for waves at Malibu was such that he became infamous for consciously trying to injure surfers who were on “his” wave by kicking out with his long board and aiming at the head of his enemy. (At left Dora pushes Johnny Fain off the wave) One of the few to have surfed Malibu in near solitude, he could not accept that those idyllic days were gone for ever. After the invasion of the “kooks”, the “king of Malibu” was not all that kingly. One average surfer, a Mexican-American named Oscar, took off on the same Malibu wave as Dora. Enraged, Dora rammed Oscar and destroyed both of their rides. Later, as Oscar sat peacefully on the beach with his family, Dora came out of the water and very belligerently demanded that Oscar (who was younger, shorter and lighter) get off “his beach” or else Dora would “beat the shit” out of him. As Oscar stood up to meet the challenge, Dora attacked him, not knowing that Oscar was a Golden Gloves boxer. After warding off Dora’s wild swings, Oscar punched “the king of Malibu” in the face and knocked him unconscious in plain view of his adoring fans. Dora was so disgraced that he didn’t show his face at Malibu for five days. Not having the humility to accept this defeat, Dora later sued Oscar for assault and was awarded $131.90 in damages, an example of the American way of punishing the victim and rewarding his aggressor. When Miki Dora went to Oahu’s North Shore in 1963 to surf the huge waves as a stuntman for a commercial surfing movie, he too came as a “kook from the valley”. To established big-wave surfers like Ricky Grigg, Dora’s arrival in Hawaii was a “nonevent”. However, his achievement was very admirable, since he learned to surf the twenty-foot waves at Waimea in one day. As his lifelong friend and big-wave surfer Greg Noll put it: “He was stiff, but he made the transition from the king of small surf to twenty-foot Waimea like nobody I’d ever seen or can think of even now. Miki did it in just one day.” Dora, like all the other big-wave surfers, had to overcome his fear to paddle out at Waimea. When he asked one big-wave surfer if he was afraid, the answer was: “Well, I’m afraid to be afraid.” Both Noll and Dora took off on one big wave that is in the movie. Dora appears hunched over and stiff since it was nearly his first time. Noll recalled that he came from behind and realized he was not going to make the wave. He came beneath Dora, put his hand on the small of his back, and gave him a helpful shove that allowed Dora to make the wave while Noll wiped out. “He probably thought I was going to push him off his board, like he’d done to a thousand people at Malibu.” This sudden display of good character surprised both of them. When Noll paddled out a half hour after his wipeout, Dora said to him: “That was the nicest thing anybody has ever done for me. Why did you do that?”

Dora’s bad character was balanced by his poetry on the waves. Every once and a while one hears about surfers who are veritable artists, having ascended to a higher level than that prevalent in professional surfing. They do not surf for judges sitting comfortably in tribunals on the beach, nor for TV and movie cameras, nor for the fans. They surf because of an “inner necessity”, and solitude is more favorable to them than cheering crowds on the beach. It is when the cameras and crowds are absent that the poet-surfer has his most intimate contact with the Ocean. Miki Dora has written about such experiences on the isolated wild coast of Namibia. Dora was totally alone with the ocean – and the sharks, unseen reefs and strong currents – risking his life in solitude with no TV cameras or adoring crowds.

Miki Dora bought his freedom at the price of being remembered as a thief, con-man and utter scoundrel. Apparently he didn’t care. One of Dora’s most disgraceful deeds revealed in Rensin’s book is assuming the identity of a dead surfing friend, Richard Roche (who died a violent death in a car crash), in order to commit further credit card scams. After the funeral of his friend, Dora went to his widow’s house in order to “console“ her, telling her, “I’m sorry about this.” Meanwhile, he milked all the information he could about Roche’s successful company from his grieving wife. Dora became Richard Roche, applied for a passport in his name, and charged $58,000 to the estate of his dead friend in forged credit cards.

Dora’s inexplicable combination of courage and cowardice, intelligence and stupidity, evokes another legendary thief who roamed the hills of Malibu long before it was invaded by Europeans: the Chumash trickster Coyote. Like Coyote, Dora could be a good companion and then steal from friends who generously opened their homes to him, or invent a brazen lie as he did in New Zealand that he never broke a single one of the ten commandments. He could adapt to all social groups, wore disguises, was sneaky, spoke in riddles, intentionally misled, was spooked by people - just like Coyote.We had made and saved a lot of money. One afternoon, while reading on the beach, I looked up at our apartment and saw Miki on our veranda. When I went home that afternoon, our money was gone.

- Australian surfer Rhonda Chagourie remembering her stay in France, 1979

After paying for his “indiscretions” with two years in different prisons, and strictly controlled probation in California after his release, Dora returned to the Atlantic coast of France, where a surfing culture has evolved similar to California’s. (At Hossegor and other coastal towns there are regular international surfing competitions.) Again Dora felt the need to depart for less crowded places. Parking his van at a friend’s place in France, he took his surfboard and his spaniel Scooter Boy (“my half-wit son”) and flew to South Africa in 1986. Having surfed Jeffreys Bay in 1971, he returned to the perfect waves there, near Cape Saint Francis made famous in Bruce Brown’s classic film Endless Summer. Dora’s legend is completed here in an amazing way. He had surfed the point break at Malibu in near isolation until Malibu deteriorated into a world famous amusement park for the rich and famous and cafe latte enthusiasts.

At Jeffreys Bay he again found a magnificent point break like virgin Malibu where he could surf with very few other surfers in the water. At this time he was well over 50 and still an astounding athlete. The young surfers there were fiercely territorial, as he and his companions had been at Malibu. Now he was the unwelcome intruder, but his amazing skill allowed him to often snatch the best waves from the younger surfers. This successful quest after the bliss of his youth on barren Californian beaches was at the cost of much loneliness. But after a few years, even Jeffreys Bay became crowded, like Malibu...

In 1970 Jeffreys Bay was still relatively unknown. It’s been deteriorating ever since (like everyplace else). However, the real treasure chest of waves lies somewhere else. No matter what the population of the world ejaculates into, nobody is going to venture into this world within a world, wherein the Final Destination is the ultimate solitude - madness or death.

- Miki Dora, “Million Days to Darkness”, Surfer July 1989

Miki Dora is much more meaningful to southern Californian culture than a mere movie star. A movie star becomes famous pretending to be someone else. Dora became famous being himself. A Euro-American Trickster. The aura of mystery surrounding his life is the mystery of being human. Most people ignore the mystery of who they are. The Mystery was the only reality for Dora. A tiny few of his rides on waves have been recorded on film. Most of his rides remain his private property never to be shared, or sublime memories of those people who saw him surf.

One such memory was shared by Australian surfer Derek Hynd in Rensin’s book: “I’ll never forget Dora’s great wave [at Jeffreys Bay]”. On his “blue beast of a board” Dora, paddled into the “Great Wave”, and put awe in everyone watching, performing “as well as he’d ever performed at Malibu.” Hynd continued: “He beached the wave. Disappeared. I never saw him surf seriously again.” (He did indeed continue seriously surfing.) Dora later related that after this ride of maybe half a kilometer, he picked up some shells on the beach which he always kept. In his 65th year, experiencing much turbulence in a jet plane on the way to Chile, he rubbed these shells for good luck. There were more magnificent waves in Chile all to himself, although a left point break was not to his liking. At 66 he was surfing in Australia, despite a sickness that was later diagnosed as pancreatic cancer. At 67, knowing that he had only months to live, he was surfing in France.

This sublime ending to the Dora legend was again marred by his bad character. His story does not evoke an ancient Greek tragedy nor comedy, but an ancient Greek “satyr play” - in between the two.* Dora rented a small apartment from friends in Jeffreys Bay, and enjoyed their hospitality upstairs in their larger, more comfortable home. He was 64, two years after the “Great Wave” and three years before his death. It was June, a cold winter month in South Africa, and Dora was watching a soccer match on TV with his friend and landlord. He had put an electric hotplate under his bed downstairs to warm it up. In his absence, his apartment caught on fire and was totally destroyed, killing Scooter Boy.

The young wife of his landlord recalled the frantic attempt to put out the fire: “He just sat there paralyzed while I screamed, ’Come on, you jerk! Come and help us!’ He wouldn’t move. He couldn’t talk.” For stupidly putting her husband, their children, their dog and their home in great peril, she kicked Dora out, saying, “I’m not your mother and you have to go... He cried - and it’s the only time I’d ever seen him cry...” Dora, now homeless and bereft of the one being who truly loved him, was shattered. “Where am I going to go?” Like the satyr Silenus in the satyr plays, Dora invented outrageous lies to explain away his bad behavior: his house was fire-bombed by people in Jeffreys Bay who hated him; his landlord set fire to the house in an insurance scam...

Jack London wrote about surfing in Hawaii in the 19th century. Shaun Tomson, world champion big wave surfer from Durban, South Africa, believes that although London was a great writer, he knew little about surfing. In the same respect, Tomson is a great surfer but is not equally as gifted as a writer. His book was co-authored by Patrick Moser, and the reader wonders what parts are Tomson’s, and what parts are Moser’s. The unique typography of the book, with very many different font faces and font sizes and colors is very distracting. As is also common in magazines, an important quote from the text is frequently repeated in a larger font in a colored text box, with no real necessity to do so. The reader’s hand need not be held in this manner. The overall effect the book had on me, however, is one of personal satisfaction, which Tomson also calls his main motivation for surfing. Bearing in mind that I really like Surfer’s Code and the philosophy it contains, there are certain basic disagreements I have with it.

Jack London wrote about surfing in Hawaii in the 19th century. Shaun Tomson, world champion big wave surfer from Durban, South Africa, believes that although London was a great writer, he knew little about surfing. In the same respect, Tomson is a great surfer but is not equally as gifted as a writer. His book was co-authored by Patrick Moser, and the reader wonders what parts are Tomson’s, and what parts are Moser’s. The unique typography of the book, with very many different font faces and font sizes and colors is very distracting. As is also common in magazines, an important quote from the text is frequently repeated in a larger font in a colored text box, with no real necessity to do so. The reader’s hand need not be held in this manner. The overall effect the book had on me, however, is one of personal satisfaction, which Tomson also calls his main motivation for surfing. Bearing in mind that I really like Surfer’s Code and the philosophy it contains, there are certain basic disagreements I have with it.

The book is divided into twelve chapters, each one a "lesson" that is elucidated on with personal reminiscences and reflections. I would not however recommend "Lesson 1" to surfers or non-surfers as words of wisdom: "I Will Never Turn My Back on the Ocean." There are several ways to understand this, but if one takes it literally or symbolically, it is nonetheless a violation of the poet’s Code "know thyself" engraved in marble over Apollo’s temple at Delphi. For many decades, tens of thousands of surfers all over the world have driven to their favorite spots, parked their cars, surfed a good day, turned their backs on the ocean, and driven back home. Turning one’s back on the Ocean is to acknowledge that a surfer, yachtsman or oceanographer are not marine mammals, but land mammals, and however much they might love the Ocean, they must return to land, their natural habitat, their only means of survival.

There is a poetic quality to Surfer’s Code that is a refreshing contrast to the excited hype prevailing in professional surfing that so disgusted Miki Dora. Tomson was able to enter this competitive commercial environment, become world champion several times, and exit gracefully: "I did not surf to compete; I competed so that I could surf." His many victories, and the resulting fame, allowed him to have the freedom to surf whenever it pleased him, wherever in the world, whether Rincon or Jeffreys Bay. The perfection he has achieved as a surfer is at certain moments transfigured into perfection of the English language. For a surfer who wants to tell his or her story, there is no where else to go than perfection of language – poetry. At this level surfing is much more than a sport. It becomes an art like music or painting. I am humbled by Shaun Tomson’s experiences in very dangerous surf from the time he was a teen-ager. In admiring the courage of fellow South African Nelson Mandela, he has achieved the same courage – not only physical courage, but spiritual courage, a much more difficult feat.

Surfing as big business took and takes up much of Shaun Tomson’s time and energy. But to encounter the Essential - everything that is sacred and good about this sport of kings - one is obliged to look elsewhere than the "surfing industry". Shaun Tomson the businessman may retort that even surfers have to pay the rent. In the history of occidental art, very often one reads of great artists who suffered enormously rather than compromise their art. Amadeo Modigliani was quite capable of surviving as a commercial artist. But he died in utter poverty with one valuable asset: the integrity beaming from his paintings.

Several times Tomson refers to the "tremendous amount of pride" he takes in calling himself a surfer. And several times I myself have referred to Pride in my books as being only detrimental to spiritual health. Leonard Peltier, the Lakota/Ojibway spiritual leader and political prisoner of over 30 years now, also refers to the first sun dancers he saw as a boy as "fiercely proud", and to the "tremendous pride" he feels as a Native American. (My Life is My Sundance) I thought this was a deadly sin? Both the oppressors and the oppressed are "fiercely proud" of their pride. Why is this universally acknowledged deadly sin universally coveted as a virtue? "Extinguish pride as quickly as you would a fire." (Herakleitos) Although ancient sages from all over the world have insisted that Pride corrupts, Shaun Tomson believes that it need not "corrupt a pure activity like surfing."

In surfing, as in thousands of other actvities practiced by the homo sapiens, Pride (one of the Seven Deadly Sins) has been magically transformed into a virtue. Strange transmigration! Making a comparison with professional golfers and baseball players, Tomson writes: "From a young age I approached surfing with the belief that it was a professional sport." This is a point of view prevalent in South African surfing that he contrasts with the "associations with drugs, drop-outs, or beach bums" of California. Now, as a former beach bum and drop-out, I am obliged to speak on behalf of another view of surfing in which Pride plays no role. Despite his criminality (like that of the medieval French burglar/poet François Villon) Miki Dora was a poet/surfer whose life demonstrates a more poetic view of surfing. Although a legend in surfing history, a veritable champion surfer, master of Jeffreys Bay before Tomson, the pride of winning a world championship meant nothing to him. A whole different vista opens up when one’s relationship with the Ocean, with Life, is not tainted by Pride, this vice of businessmen and professional athletes. (Another "drop-out" from California: Everett Ruess)