|

|

A misleading metaphor can do a lot of damage especially when it is a metaphor for the world itself. In today's post, I'm going to discuss four metaphors for the natural world. I shall attempt to explain why I and many other Intelligent Design proponents believe that the metaphor of a watch, which is generally associated with William Paley (1743-1805), is an inadequate metaphor for the natural world. After that, I'll discuss what I consider to be three better metaphors for the world: a lute, a recipe and a symphony.

This post will also address a profound philosophical issue: what accounts for the "thinginess" of the things we find in the world? What makes a thing a thing? The question may sound a little abstruse, but it is actually of immense practical significance. Getting the answer to this question wrong can cause philosophers to over-exaggerate the reality of natural objects, causing them to falsely believe that things don't need a Creator to sustain them in existence. At the other extreme, philosophers may fall into the trap of minimizing the reality of things to such a degree that they are no longer real things at all, but merely simulations, like the "things" in the Virtual Reality world of The Matrix.

What prompted me to write this post was a recent online talk given by Professor Edward Feser at the Science and Faith Conference, held at the Franciscan University of Steubenville on December 3, 2011. I would strongly recommend that readers take the time to listen to Professor Feser's presentation, "Natural Theology Must Be Grounded in the Philosophy of Nature, Not Natural Science", as it is a crushing refutation of the arrogant pretensions of modern atheistic scientists, who believe science is fully capable of resolving the ultimate questions about Nature, without recourse to philosophy. Natural theology, argues Feser, has to be grounded in the philosophy of nature, if it is to get you to the God of classical theism.

Professor Feser's talk also contains a succinct exposition of the chief philosophical and theological objection made by some (but not all) Thomist philosophers to the notion of Intelligent Design. In layperson's language, Feser contends that ID is incapable of accounting for the built-in tendencies of natural objects. These tendencies endow things with their very "thinginess." Without these built-in tendencies, the world would be something like The Matrix; it wouldn't be a real world. Since Intelligent Design fails to account for the "thinginess" of things, Feser concludes that it is therefore of no help whatsoever when attempting to argue for the existence of a Creator Who made (and Who maintains in existence) each and every thing. What's more, says Feser, if things themselves are construed as artifacts, then it becomes impossible in principle to philosophically demonstrate that they need someone to maintain them in existence; all one could ever hope to show is that their parts need to be held together by an Intelligent Agent. The God of classical theism, however, is more than a mere Demiurge; He endows things with their very being.

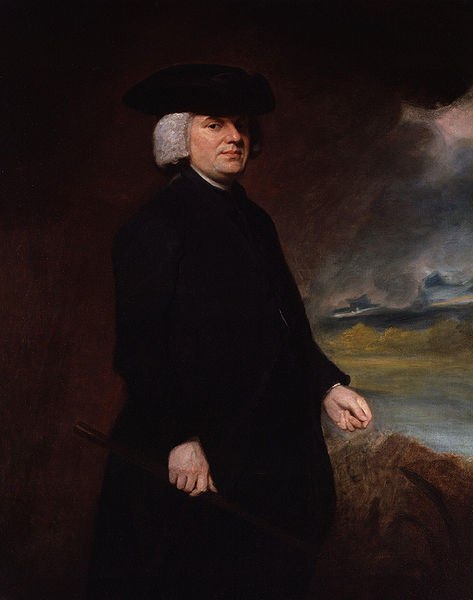

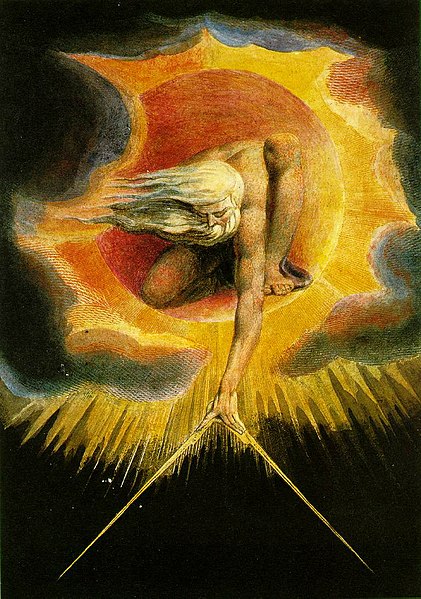

During his talk, Feser discusses the theology of William Paley, who famously likened a living organism to a watch, which must have been made by a Divine Watchmaker. Feser focuses on the watch metaphor, because it encapsulates what he thinks is wrong with Intelligent Design.

This post (which is the first of two posts in reply to Professor Feser) will be divided into eight parts:

|

1. PART ONE: Professor Feser's claim that Intelligent Design is unable to account for the "thinginess" of natural objects ID proponents' willingness to adopt artifactual metaphors to describe objects in Nature which they consider to have been designed, leaves them unable to account for the "thinginess" of objects. Without this "thinginess" the world would be nothing more than a giant simulation.

2. PART TWO: Why Professor Feser thinks ID proponents have an emaciated view of living things

3. PART THREE: Why medieval Scholasticism accords well with the way in which Intelligent Design proponents talk about living things

4. PART FOUR: Is Intelligent Design wedded to a mechanistic view of living things?

5. PART FIVE: Why Intelligent Design has to be bottom-up as well as top-down

6. PART SIX: The origin of the clockwork universe metaphor

7. PART SEVEN: Was Paley wrong in likening natural objects to artifacts?

8. PART EIGHT: Getting past the watch metaphor: three better metaphors for the cosmos |

|

|

|

Left: Professor Edward Feser, a Thomistic critic of Intelligent Design. Image taken from http://www.edwardfeser.com/.

Middle: A Russian mechanical watch. A watch's purpose is to tell the time. However, the parts of a watch have no inherent tendency to function together as a time-keeping device. Their purpose is extrinsic to their natures: it is imposed on them from outside. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

Right: A brain in a vat, rather like the ones in the movie The Matrix. Professor Feser argues that if natural causes have no inherent tendency to produce their characteristic effects, then they are not genuine causes at all. It would be really God - and only God - who brings about the effects they are said to "produce". Such a view would rob things of their very "thinghood". It would mean that the world we are living in is really an illusory one, like The Matrix. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

In the course of his presentation at the Science and Faith Conference, held at the Franciscan University of Steubenville on December 3, 2011, Professor Feser addressed his cardinal difficulty with Intelligent Design. Specifically, Feser's objection related to the notion of immanent finality, a property of natural causes which he defined as their inherent tendency to "point to" or be "directed at" their characteristic effects. To adapt one of Feser's favorite examples, when white phosphorus (which was used in some old matches) is exposed to air, it tends to ignite and generate fire and heat, rather than (say) frost and cold. (I say "tends to", because interfering circumstances may prevent it from reacting in the usual manner, of course.)

Feser contrasted the immanent finality of natural substances with the extrinsic finality of an artifact, which, he maintains, resides not in the artifact itself, but in the mind of its designer (and the people using it). For example, we say that the hands of a watch "point to" the correct time (say, 5:20 p.m.), but that's because the people who design watches intend the "5" on the dial to mean "five hours after mid-day" when the hour hand points to it during the daytime, while the "4" on the dial is taken to mean "twenty minutes after the hour" when the minute hand points to it. If it were not for these human conventions, the hands on a watch wouldn't mean anything when they pointed at those numbers on the dial.

Professor Feser then argued that when Intelligent Design proponents speak of meaningful patterns being imposed on objects by a Designer, they thereby externalize the proper functions of objects, effectively treating them as if they were artifacts that possessed only extrinsic finality. Rev. William Paley's watch metaphor reinforces this way of thinking. The danger of regarding natural objects as having been designed in this way is that their purpose or function would then reside only in the mind of their Maker (God), which would leave no room for us to speak of these natural objects as having any inherent causal powers of their own. In effect, the watch metaphor, when applied to things in the natural world, takes their very "thinginess" out of them, by robbing them of their causal agency. God becomes the only causal agent, and the world becomes a virtual world, like something out of The Matrix. As Feser put it in his talk:

If natural objects are to be true causes they must possess immanent finality and not merely extrinsic finality.To deny them immanent finality, and to hold that whatever finality they have resides only in the divine intellect, in the manner that the time-telling function resides in the designer of a watch, and in no way in the natural objects themselves immanently, would therefore seem to entail denying natural objects genuine causal powers, and to attribute all causal powers to God alone - and that would be an embrace of occasionalism.

Insofar as Paley's position denies immanent finality, it therefore threatens to collapse into occasionalism.

I have some good news for Professor Feser: it may interest him to know that some of Intelligent Design's leading proponents have publicly rejected Paley's watch metaphor. I'll say more about this below.

Occasionalism, for those readers who may be wondering, is the extremely odd view, held by a number of medieval Arab philosophers (as well as a handful of Christian philosophers), that natural objects never really cause anything to happen, and that when they appear to do so, it is really God - and only God - who brings about the effects. On this view, a flame, to use a medieval example, does not burn the piece of cotton that it comes into contact with; rather, it is God who burns the piece of cotton on the occasion of its being brought near a flame. The danger of this view is that by robbing things of their agency, it also robs them of their "thinghood" or "thinginess."

At the other extreme, mere conservationism refers to the view that God conserves all natural causes in being, but that His involvement in producing changes in the world is an indirect one, at best: He is either a remote cause (the first in a long chain of causes) or He doesn't cause change at all, but simply maintains in existence things that have the built-in ability to change themselves automatically, without Him having to do anything extra. The danger of this view is that it marginalizes God, reducing His causal role in events that take place in the world: He become either a remote Deity or a merely permissive one. Only one medieval thinker - Durandus - upheld this view.

Professor Feser, like myself, is neither an occasionalist nor a mere conservationist but a concurrentist: he holds that natural causes do indeed bring about their effects, but that when they do so, God does not merely act as a First Cause which conserves the natural cause in being. God does more than that. God also acts in co-operation with each natural cause to bring about its effect immediately. Thus both God and the natural cause are in immediate contact with the effect they produce. This was the view of Divine causality taken by nearly all medieval Christian philosophers. The chief advantage of this view is that it maximizes the causal roles of both God and natural agents.

|

|

A liana vine (left) and a hammock (right), are used by Professor Feser to illustrate the difference between natural objects, which exhibit immanent finality, and artifacts, which exhibit extrinsic finality. Images courtesy of Wikipedia.

Unfortunately, Professor Feser was a little imprecise in his talk at the Franciscan University of Steubenville on December 3, 2011, when he attempted to explain the difference between immanent and extrinsic finality. While it is arguably true for an artifact such as a watch that its time-telling function resides purely in the mind of its human designer and users, it is certainly not true of all artifacts. For instance, it would not be accurate to say of a knife, that its function of cutting resides only in the mind of its maker and the people using it. An alien archaeologist visiting Earth long after human beings had become extinct could, upon digging up a buried knife, instantly recognize that it was intended for cutting something. A knife wears its function on its sleeve, as it were.

Happily, Feser himself has provided a much clearer exposition of the precise difference between the immanent finality of natural objects and the extrinsic finality of artifacts in an online post of his, entitled, Nature versus Art (30 April 2011). Here, Feser explains that the parts of natural objects have an inherent tendency to function together, because they share a substantial unity: they are parts of one thing. In Aristotelian jargon, the inherent unity of these parts is the result of their substantial form, which makes them one substance.

The unity of an artifact, on the other hand, is a merely accidental one, in which the parts have no inherent tendency to function together. An artifact only functions because an external agent brought together its parts and imposed some arrangement upon them, enabling them to perform some task. The parts of an artifact don't share a common substantial form; the only form they share in common is the artificially imposed arrangement of their parts. (In Aristotelian terminology, such a form is described as accidental, which doesn't mean "happenstance"; rather, it simply means that the form is not a substantial one in other words, they're not really parts of one thing.) Hence an artifact cannot truly be described as a single entity. It is an assemblage.

|

|

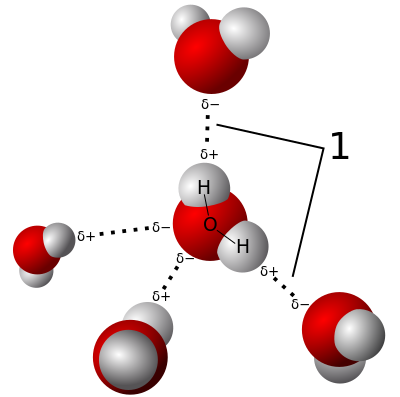

Left: A model of hydrogen bonds in water, showing partial positive and negative charges. Image courtesy of Qwerter and Wikipedia.

The molecules of water are constantly moving in relation to each other, and the hydrogen bonds are continually breaking and reforming. However, these hydrogen bonds are sufficiently strong to create many of the peculiar properties of water, such as those that make it integral to life. Thanks to hydrogen bonding, water molecules have an inherent tendency to function together, giving them novel causal powers and chemical properties that they would otherwise have lacked. In other words, water molecules collectively exhibit what Professor Feser refers to as immanent finality. This example illustrates the fact that immanent finality can be found in inanimate natural objects, as well as in living things.

Right: A paper clip floating in a glass of water. Image courtesy of Alvesgaspar and Wikipedia.

The floating paper clip illustrates the phenomenon of surface tension, in which the molecules of water function together as a whole, to keep the clip afloat. This behavior is an example of immanent finality, as displayed by inanimate natural objects. In the bulk of the liquid, each molecule is pulled equally in every direction by neighboring liquid molecules, resulting in a net force of zero. However, the molecules at the surface of the water do not have other molecules on all sides of them and therefore are pulled inwards. This creates internal pressure and forces liquid surfaces to contract to the minimal area.

In the passage below, Professor Feser uses the example of a liana vine to illustrate the notion of immanent finality. I would like to stress that on Feser's view, it is not merely living things, such as liana vines, that possess immanent finality. Any kind of natural object, living or non-living, whose parts have an inherent tendency to function together can be said to possess immanent finality. The surface tension of water (illustrated above) would be one example of immanent finality in an inanimate object.

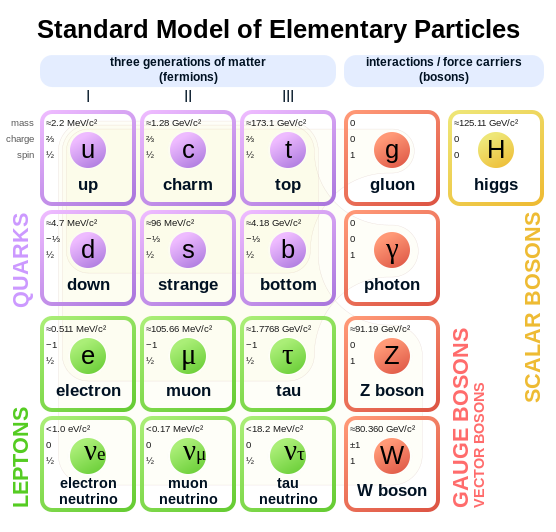

For the benefit of those readers who are new to Aristotelian philosophy, I should explain that when Feser writes about substantial form in the passage quoted below, he simply means: that which gives a thing its very nature, making it the kind of thing it is. Aristotle taught that the things we see in Nature all belong to various natural kinds, each with its own distinct essence, and for Thomists such as Professor Feser, each kind of natural object has one, and only one, substantial form. For instance, an electron's substantial form is what makes it an electron and not a quark; myoglobin's substantial form is what makes it that protein, and not some other kind; and a panda's substantial form is what makes it a panda, and not a polar bear. (I realize that all this invites the obvious question: where do you draw the line between the various natural kinds, and how? That's a big topic, and I won't be discussing it here. All I want to say is that the claim that natural kinds are objectively real makes excellent sense, especially if you're doing physics and chemistry. Think of the Standard Model. Think of the periodic table. In biology, many people disparage the idea of "essences" or natural kinds, but that's because they're mistakenly equating natural kinds with biological species, which can merge into one another. At higher levels of taxonomy, however, the boundaries are very clearcut. For example, each phylum of animals has its own distinctive body plan. What's the lowest level of taxonomy where we can still speak of clearcut "natural kinds"? Probably the level of the order, or possibly family. That's an ongoing topic for research.)

For people with a chemistry background, it may be very tempting to equate substantial form with the concept of atomic or molecular structure. Tempting, but wrong. The equation of substantial form with structure only works for substances that are either atoms or molecules. It doesn't work for simple subatomic particles, which have no structure (e.g. electrons). It doesn't work for the spatially diffuse fields that physicists love to talk about. It doesn't even work in all areas of chemistry - for a complex biomolecule, the substantial form which gives it its distinct identity is a matter of sequence, rather than structure. And the equation of form with structure certainly doesn't work for living things. Biologists don't "slice and dice" the natural world just by looking at structure.

Aristotle referred to a living thing's unique substantial form as its soul - which certainly doesn't mean some kind of spirit or spook. For both living and non-living things, the substantial form is simply a realization of the underlying matter. (Thomists regard this "underlying matter" as being utterly devoid of all form; other Scholastic philosophers disagree. I'll say more on that in Parts Two and Three.)

In the discussion which follows, it's important to keep in mind that a thing's substantial form belongs to its innermost essence. (Technically, the essence of a thing is the underlying matter plus the substantial form.) By contrast, an accidental form (such as shape, size or color) is a property of a thing, rather than part of its essence.

Let us now examine how Professor Feser explains the contrast between immanent finality in his online post, Nature versus Art (30 April 2011):

Let's illustrate the distinction in terms of a simple example. A liana vine the kind of vine Tarzan likes to swing on is a natural object. A hammock that Tarzan might construct from living liana vines is an artifact. The parts of the liana vine have an inherent tendency to function together to allow the liana to exhibit the growth patterns it does, to take in water and nutrients, and so forth. By contrast, the parts of the hammock the liana vines themselves have no inherent tendency to function together as a hammock. Rather, they must be arranged by Tarzan to do so...What is true of hammocks is from an A-T [Aristotelian-Thomistic] point of view true also of watches, cars, computers, houses, airplanes, telephones, cups, coats, beds, doorstops, and countless other things. Like the hammock, they are artifacts rather than true substances because their specifically watch-like, car-like, computer-like, etc. tendencies are extrinsic rather than immanent, the result of externally imposed accidental forms rather than substantial forms...

Hammocks made out of liana vines are artifacts, but liana vines themselves are not and could not be. The notion of an artifact presupposes the natural substances out of which it is made, so that (from an A-T point of view, anyway) it can hardly make sense to think of natural substances themselves as "artifacts."...

[N]atural objects are not artifacts, and that's why God doesn't make ... natural objects that are artifacts...

(Bold emphases mine, italics Feser's VJT.)

In the passage above, Professor Feser refers to the (accidental) forms of artifacts (such as a hammock) as being externally imposed, which seems to imply that the (substantial) forms of natural objects (such as a liana vine) are not imposed from outside. He also declares that artifacts are not true substances, as "their specifically watch-like, car-like, computer-like, etc. tendencies are extrinsic rather than immanent, the result of externally imposed accidental forms rather than substantial forms" (italics mine). Thus it is fair to conclude that one of the criteria by which Feser distinguishes immanent finality from extrinsic finality is that the functionality of a natural object cannot be externally imposed, whereas the functionality of an artifact can only be externally imposed, because it is not a natural form.

When Feser states in the passage above that the parts of natural objects (such as liana vines) having an inherent tendency to function together, he does not directly address the question of whether they have an inherent tendency to come together in the first place. However, in an earlier post entitled, ID theory, Aquinas, and the origin of life: A reply to Torley (April 16, 2010), Feser refers to "the making of a mousetrap or a watch, which unlike water and living things have no natural tendency to come into existence in the first place." Additionally, on page 137 of his book Aquinas (Oneworld, Oxford, 2009), Feser writes that "the parts of an artifact have no inherent tendency to come together" which might reasonably be taken to imply that the parts of a natural object do have such a tendency. Thus for Feser, one difference between the immanent finality of a natural object and the extrinsic finality of an artifact is that the parts of a natural object have a natural tendency to come together, while the parts of an artifact do not.

So now it seems as if there are four distinguishing features of immanent finality, according to Feser:

1. In a natural object, which possesses immanent finality, the parts have an inherent tendency to function together. The parts of an artifact lack such an inherent tendency.

2. The functionality of an object exhibiting immanent finality is explained by its substantial form, which gives the object its nature. The functionality of an artifact, on the other hand, is the product of its accidental form - usually, the highly artificial arrangement of its parts.

3. In an object exhibiting immanent finality, the functionality cannot be imposed from outside. By contrast, the functionality of artifacts can only be imposed from outside, as it is not natural.

4. Natural objects exhibiting immanent finality tend to arise in Nature, because their parts have an inherent tendency to come together in the first place. Artifacts, on the other hand, have to be manufactured; their parts have no natural tendency to come together.

The Standard Model of elementary particles, showing the 12 fundamental fermions and 4 fundamental bosons, shows how natural objects can possess immanent finality even if they lack physical parts. Elementary particles are believed to have no physical parts: consequently, on Professor Feser's definition above, they would lack immanent finality, which he defined as having parts with an inherent tendency to function together. However, these particles undeniably possess inherent tendencies, distinguishing them from artifacts. This example suggests that Feser's definition of immanent finality needs to be broadened. Image courtesy of MissMJ, PBS NOVA, Fermilab, Office of Science, United States Department of Energy, Particle Data Group and Wikipedia.

A brief comment on Feser's four criteria for distinguishing immanent finality from extrinsic finality

I would contend that Professor Feser's first criterion needs to be modified, as not all natural objects have physical (as opposed to metaphysical) parts. For instance, an electron (shown in the illustration above, depicting the fundamental particles in the Standard Model) can be regarded as point-sized (and hence structureless), when it is behaving as a particle. Despite lacking physical parts, it still possesses inherent tendencies - for instance, it tends to electrically repel other electrons and be attracted to protons. So Feser should say that a natural object possesses inherent tendencies, and that if it is composed of physical parts, these parts will also have an inherent tendency to function together.

Feser's second criterion is uncontroversial: no-one who accepts the reality of Aristotelian substantial forms could possibly find fault with it.

Feser's third and fourth criteria, however, require drastic revision. The third criterion is obviously flawed, as it is quite easy to show that the functionality of a natural object can be externally imposed. Lastly, Feser's final criterion mistakenly conflates a thing's origin with its function. The mere fact that the parts of a natural object have an inherent tendency to function together gives us absolutely no reason to believe that they had a natural tendency to come together, in the first place, as Feser supposes.

In the passage on liana vines and hammocks which I quoted in section 1.2 above, Professor Feser referred to the (accidental) forms of artifacts (such as a hammock) as being externally imposed, which seems to imply that the (substantial) forms of natural objects (such as a liana vine) are not imposed from outside.

However, there is a legitimate sense in which even Thomistic philosophers, such as Feser, can speak of the substantial form of a natural object being externally imposed on matter. For Thomists like Feser, this form would have to be imposed on prime matter - i.e. matter devoid of all form, or in other words, in other words, pure passive potency. For Thomists, prime matter has no positive features whatsoever, so it would be dangerously wrong to regard it as some kind of "stuff". Nevertheless, it can be legitimately described as the ultimate substrate of change, in natural objects.

I'd now like to discuss three cases where Professor Feser would have to acknowledge that the substantial form of a natural object is externally imposed.

Case One: The synthesis of water

|

|

|

Left: Close-up view of a Space Shuttle Main Engine during a test firing at the John C. Stennis Space Center in Hancock County, Mississippi. The Space Shuttle Main Engine burnt hydrogen with oxygen, producing water vapor. Image courtesy of NASA and Wikipedia.

Middle: A picture of Henry Cavendish, by George Wilson. 1851. Cavendish was the first man to create water by burning hydrogen gas, in 1781.

Right: Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier. In 1783, Lavoisier and Laplace replicated Cavendish's finding that water is produced when hydrogen is burned. Line engraving by Louis Jean Desire Delaistre, after a design by Julien Leopold Boilly.

In a previous post entitled, ID theory, Aquinas, and the origin of life: A reply to Torley (April 16, 2010), Professor Feser has himself acknowledged that the substantial form of a natural object (which confers a genuine unity upon it, and thereby makes it a true substance) can be externally imposed by intelligent human beings. One example he gave in his post was that of scientists synthesize water in a laboratory. In such a case, insisted Feser, the water is not an artifact, as the atoms have a built-in tendency to come together. But regardless of whether we call water that was made in a laboratory an artifact or not, it is undeniably true that the form is externally imposed by scientists taking advantage of the laws of chemistry. In such a case, Thomist philosophers would say that the substantial form of water is externally imposed on prime matter, rather than on the constituent elements of hydrogen and oxygen, as they maintain that each natural object has one and only one substantial form. (I'll say more about this below.) This explains why Feser wrote in in a recent post (July 5, 2012) that "the hydrogen and oxygen in ... [water] exist only 'virtually' rather than 'actually.'"

Case Two: Scientists intelligently generating life from non-living matter

|

|

Left: Professor George Church, of Harvard Medical School, marveling at a molecular model at TED 2010. Church is interested in the creation of a synthetic cell, starting from scratch. He has publicly stated, "Biology presents a unique opportunity to run trillions of experiments that are atomically precise. If we recreate life as a chiral mirror image, it might have radical new properties." Image courtesy of Steve Jurvetson and Wikipedia.

Right: Synthetic chemist Julie Perkins works to link two molecules, each of which binds to two protein binding sites. Image courtesy of Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory and Wikipedia.

In his online post entitled, ID theory, Aquinas and the Origins of Life: A Reply to Torley (April 16, 2010), Professor Feser also allowed for the theoretical possibility that scientists might one day be able to intelligently generate a living organism using the raw materials of life. (I presume he means organic molecules such as amino acids and nucleotides.) Feser thinks that scientists could conceivably do this, but only if there is "some final causality already built into nature" which would allow them to "use non-living materials that nevertheless have immanent causation definitive of life within them, 'virtually'". However, Feser thinks this scenario is highly unlikely, because of "the absence of any evidence for spontaneous generation." If it were to happen, though, it could only be accomplished through a radical change of nature: the old substantial form of the raw materials would have to be displaced by the new form of a living organism. The new substantial form of the organism would thus be externally imposed on prime matter - i.e. matter devoid of all form.

Case Three: God making a man from dust

Adam and Eve, by Lucas Cranach the Elder. Bode Museum. Oil on beech wood, 1533. Image courtesy of Till Niermann and Wikipedia.

Professor Feser happily concedes that God could, if He wished, impose the substantial form of a man (i.e. a human soul) on the dust of the ground, as in Genesis 2:7. If He chose to do so, however, Feser maintains that the substantial form of a man would displace the substantial form of dust. Also, says Feser, there would be no need for God to reconfigure the dust, as an Artificer would do: He could simply command it to become a man.

Finally, Professor Feser has acknowledged that God could, if He wished, make a man from the dust of the ground. If God did so, He would be imposing the substantial form of a man (i.e. the human soul) on prime matter, and this new form would replace the old form that characterized dust.

In a comment on his post, Nature versus Art (April 30, 2011), Feser asserted that God could, if He wished, make a man from the dust of the ground, simply by saying, "Dust, become a man", without needing to rearrange or reconfigure the dust, in the way that an artificer would need to do, if he were making something new from dust. In this case, God would be imposing the substantial form of a man on prime matter, and this form would replace the old substantial form that characterized dust. (I'll say more about this claim in Part Five below; contra Feser, I think God would have to reorganize the dust, atom by atom, from the bottom up, and that top-down-only transformations are metaphysically impossible, even for God.)

One might try to amend Feser's third criterion for distinguishing natural objects from artifacts, as follows: whereas the form of an artifact has to be externally imposed, the form of a natural object does not, although it may be imposed from outside by an intelligent being. But even this is highly problematic, as it assumes that the forms of all natural objects are capable of arising as a result of natural physical processes, without the need for an intelligent agent to impose them. This is a very questionable assumption, as I'll argue below.

It seems that the safest way to preserve the essence of Feser's third criterion is to simply say that for a natural object exhibiting immanent finality, the functionality can be imposed from outside, but only by destroying the nature of the thing it is imposed upon, leaving nothing but prime matter as the underlying substrate of change.

Even if the chemical constituents of life have a built-in capacity to assemble themselves together, the example of hurdling illustrates the reason why the probability of these constituents naturally exercising this capacity is vanishingly low. In short: there are too many obstacles to be overcome, and even during the 13.7 billion year history of the universe, the likelihood that they will be overcome is astronomically low. It takes the direction of an intelligent agent to overcome all of these obstacles. Image courtesy of Rodrigo Moraes and Wikipedia.

In section 1.2 above, I remarked that the inherent tendency of the parts of a natural object to function together does not logically entail that they have a tendency to come together in the first place. For example, the parts of a living thing certainly have an inherent tendency to function together, but it does not follow from this that they have any natural tendency to come together from non-living matter. As I have written elsewhere: "The intrinsic finality we find in all living things cannot account for the coming-to-be of the first living things."

Curiously, Feser appears to agree with me on this point. In his post Aquinas on the origin of life: A reply to Torley (April 16, 2010), Feser is openly skeptical of the notion that there are inorganic natural processes which are "virtually" capable of generating life, under the right circumstances (abiogenesis).

Indeed, Professor Feser is strongly inclined to think that the molecules composing a living thing have no built-in capacity to assemble themselves into a living thing. In his post, ID theory, Aquinas, and the origin of life: A reply to Torley (April 16, 2010), Feser wrote:

...[T]he view that life cannot arise from non-life is in fact itself a commonplace of the A-T [Aristotelian-Thomistic] tradition, even if it is not the subject I was addressing. Not only do I not object to that view, I warmly endorse it.

However, Feser also maintains that if the various molecules composing a living thing could somehow be assembled by intelligent agents (e.g. scientists of the future) into a living thing, this would mean that the molecules composing a living thing do, after all, have a built-in capacity to assemble themselves into a living thing. For the scientists to do their job, they would have to make use of "some final causality already built into nature", enabling them to "use non-living materials that nevertheless have immanent causation definitive of life within them, 'virtually'" (bold emphases mine). It may even be the case that in the process, "the scientists did something to the raw materials that could not have happened in the absence of an intelligence like their own." Such a scenario, writes Feser, "is an eccentric but still natural way of generating life, just as the synthesis of water is. It isn't like the making of a mousetrap or a watch, which unlike water and living things have no natural tendency to come into existence in the first place."

Why intelligently generating a life-form from scratch isn't like synthesizing water in a laboratory

Unfortunately, there is a gap in Professor Feser's metaphysical reasoning here. The hydrogen and oxygen molecules from which water is generated have an active tendency to assemble themselves into water. As Wikipedia informs us in its article on hydrogen:

Hydrogen gas (dihydrogen or molecular hydrogen) is highly flammable and will burn in air at a very wide range of concentrations between 4% and 75% by volume. The enthalpy of combustion for hydrogen is −286 kJ/mol.

- 2 H2(g) + O2(g) → 2 H2O(l) + 572 kJ (286 kJ/mol) [energy per mole of the combustible material (hydrogen)]

Hydrogen gas forms explosive mixtures with air if it is 474% concentrated and with chlorine if it is 595% concentrated. The mixtures spontaneously explode by spark, heat or sunlight. The hydrogen autoignition temperature, the temperature of spontaneous ignition in air, is 500 °C (932 °F).

With living things, the situation is different. Even if the molecules composing a living thing have a built-in passive capacity to be assembled by clever scientists into a living thing, that would in no way imply that these molecules have the active capacity to assemble themselves into a living thing. What Professor Dembski is denying that the chemical constituents of life possess is the active capacity to assemble themselves, not the passive capacity to be assembled.

Interestingly, Feser himself acknowledges, in his post, ID theory, Aquinas, and the origin of life: A reply to Torley (April 16, 2010), that scientists generating life might do "something to the raw materials that could not have happened in the absence of an intelligence like their own", which implies that the raw materials obviously lack the capacity to assemble themselves into a living thing. In other words, a living thing has no natural tendency to come into existence in the first place. Amazingly, however, Feser then goes on to say that a watch, unlike water and living things, has "no natural tendency to come into existence in the first place", which would mean that living things do have such a tendency. Feser is thus contradicting himself in the same post, on the question of whether life has a natural tendency to come into existence.

Mere possibility versus probability

Four colored six-sided dice, arranged in an aesthetic way. All six possible sides are visible. Image courtesy of Diacritica and Wikipedia.

The notion of probability seems to constitute a major headache for Aristotle's metaphysics, which divides everything into two fundamental categories: potency and act. Probability fits in neither category. Potency is a binary, yes-no affair: it's something that an entity either has or it lacks. Probability, on the other hand, is quantifiable: it is represented by a number. On the other hand, probability cannot be identified with actuality, except in the case when it is equal to exactly 1.

Let us grant for the sake of argument that the chemical constituents of life do possess an active built-in capacity to assemble themselves into a living thing, because they "have immanent causation definitive of life within them, 'virtually'", to use Feser's words. Even so, there is still a vital difference between the natural tendency of hydrogen and oxygen to assemble themselves into water and the tendency of the chemical constituents of life to assemble themselves into a living thing. That difference can be summed up in one simple word: probability.

Even if the chemical constituents of life could (under the right circumstances) assemble themselves into a living thing, the probability of them naturally exercising this capacity may be vanishingly low, because there are so many chemical and energetic hurdles to be overcome. Indeed, according to Intelligent Design proponent Dr. Stephen Meyer, the odds of life forming as a result of natural processes are so low that we would not normally expect it to occur even once in the entire history of the observable universe.

What an intelligent agent can do, by a judicious manipulation of the ingredients of life, is to bring together individual molecules in a very cleverly-timed sequence of chemical steps, which in the state of Nature would have been astronomically unlikely to occur. A sufficiently clever and skillful intelligent agent could take these chemical constituents of life and build them into a living thing, with a probability of success of 100%. The role of intelligent agency here is to transform an active potency within the chemical constituents of life which is extremely unlikely to be realized, into a potency which is guaranteed to be realized.

Professor Feser thinks that thge most significant element in the above narrative is that the built-in capacity already exists within the constituents of life, making the generation of life different from the creation of a watch. But this argument can no longer be sustained if the probability of the chemical constituents of life naturally assembling themselves into a living thing is far lower than the probability of natural materials assembling themselves into a watch.

I might point out in passing that the notion of probability does not sit easily within Aristotle's metaphysical system, which divides everything into two fundamental categories: potency and act. Probability appears to belong in neither category. Potency is a binary, yes-no affair: it's something that an entity either has or it lacks. Probability, on the other hand, is quantifiable. It is represented by a number: for example, the probability of a die's landing on the number 3 is 1 in 6, or 0.166666.... Nor can probability be identified with actuality, except in the rare case when it happens to equal exactly one. A modern Aristotelian-Thomist might attempt to circumvent this difficulty, by saying that a die (for instance) has the actual property of having an equal chance of landing on any of its six sides. But that leaves the term "chance" undefined, and we are back where we started.

Conclusion

After critiquing Feser's four criteria for distinguishing immanent from extrinsic finality, I would now like to propose that they be re-written as follows:

1. A natural object possesses inherent tendencies, by virtue of the fact that it possesses immanent finality. If a natural object is composed of physical parts, these parts will also have an inherent tendency to function together, as they share a common substantial form, making them parts of a single entity. The parts of an artifact, on the other hand, lack such an inherent tendency, as they do not share a common substantial form. Hence the finality of an artifact is merely extrinsic.

2. The functionality of an object exhibiting immanent finality is explained by its substantial form, which gives the object its nature. The functionality of an artifact, on the other hand, is the product of its accidental form - usually, the highly artificial arrangement of its parts.

3. For a natural object exhibiting immanent finality, the functionality can be imposed from outside, but only by destroying the nature of the thing it is imposed upon, leaving nothing but prime matter (matter devoid of any form) as the underlying substrate of change. By contrast, the functionality of artifacts can only be imposed from outside, because it is not natural. The functionality of an artifact is always imposed upon a pre-existing object, whose underlying substantial form is left intact in the process.

4. The parts of natural objects exhibiting immanent finality may or may not have an inherent tendency to come together in the first place, depending on the kind of object in question. The parts of artifacts, on the other hand, have no natural tendency to come together; by definition, they have to be designed. Natural objects may also need to be designed, but even if this is so, it is not true by definition, as in the case of artifacts.

A little horse on wheels, discovered in the Ancient Greek city of Troy in a tomb dating 950-900 BC. Kerameikos Archaeological Museum in Athens. Image courtesy of Sharon Mollerus and Wikipedia.

Professor Feser argues that it's no use arguing that objects are designed, if the metaphor you use for describing natural objects prevents you from ever arguing that they need Someone to maintain them in existence. If objects are construed as artifacts, along the model of toys, then God is reduced to a mere Cosmic Toymaker, rather than the One who gives things their very being (Acts 17:28).

We are now able to address the question: what is Professor Feser's big beef with Intelligent Design?

In a nutshell, Feser's principal theological (and philosophical) objection to Intelligent Design is that ID proponents' willingness even if purely for the sake of argument to adopt artifactual metaphors to describe those objects in Nature which they consider to have been designed, renders them unable to account for the most basic features of objects, without which they would not be objects at all: namely, their causal powers. It is no use, contends Feser, to argue that objects are designed, if you "de-objectify" them in the process, and rob them of their causal agency. The agent whose existence you establish will not be a God worthy of the name.

What's more, says Feser, your argument can never hope to establish the existence of a Designer Who is identical with - or Who is even compatible with - the God of classical theism. For the God of classical theism is a God Who is needed to maintain things in existence. But if things are construed as artifacts, then it becomes impossible in principle to demonstrate philosophically that they need someone to maintain them in existence. All one could hope to show is that they need an intelligent agent to assemble (and perhaps hold together) their parts - in other words, a Demiurge, not a Creator. God would then be akin to a Cosmic Toymaker. The God of classical theism, however, is more than a mere Demiurge; He endows things with their very being. For our God is a God who made things, not toys.

Or as Feser himself put it in his online post, Nature versus Art (30 April 2011):

[S]ince natural objects are (for the A-T philosopher) simply not artifacts in the relevant sense, it is a waste of time to argue for a divine designer on the basis of the assumption that they are, even if this assumption is made only "for the sake of argument."... The point is that this is not a good way to begin an argument for the existence of God, because the key premise of the argument is false and because the implications of the comparison it rests on are dangerously misleading if used as a way of developing a conception of God's relationship to the world. (Bold emphases mine, italics Feser's VJT.)

The theological objection Feser puts forward here is certainly a formidable one. In this post, I intend to show that Intelligent Design proponents do not, in fact, model things on artifacts, and that their preferred metaphors for describing the relationship of God to the world highlight creation's intimate, ongoing dependence on God. The larger question of how an Intelligent Design advocate could argue for the reality of a God Who conserves things in existence is one which I will address in my next post.

|

|

|

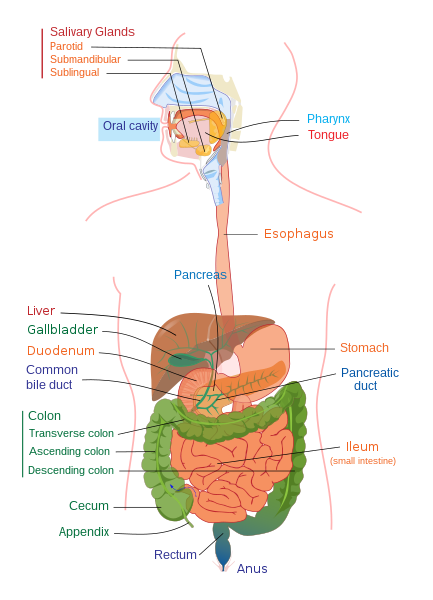

Left: The human digestive system. Image courtesy of Mariana Ruiz ("Lady of Hats") and Wikipedia.

The process of digestion illustrates what Professor Feser regards as the essential difference between living things and other natural causes. All natural causes have an inherent tendency to produce their effects, but living things are distinguished by causal processes that begin and remain within the agent itself, and which typically benefit the agent. This kind of causation is what Feser calls immanent causation. For example, in digestion, the mechanical and chemical breakdown of food into smaller components that are more easily absorbed into an animal's bloodstream occurs within the body of an animal, and helps it to grow and nourish itself.

Middle: A lodestone, or natural magnet, attracting iron nails. This is an example of transeunt causation, which is defined by Professor Feser in his book Aquinas (Oneworld, Oxford, 2009, p. 135): "Transeunt causation ... is directed entirely outwardly, from the cause to an external effect... One rock knocking another off the side of a cliff would be an example of transeunt causation." Thus the key difference between immanent causation and transeunt causation is that in the former case, causal processes remain within the agent itself, whereas in the latter case, they are directed exclusively at an outward effect. Although an inanimate natural object such as a lodestone does not exhibit immanent causation, it still exhibit immanent finality, because the atoms of which it is composed have an inherent tendency to function together as a magnet. Image courtesy of Fred Anzley Annet (Electrical Machinery: A practical study course on installation, operation, and maintenance, 1st Ed., McGraw-Hill, New York, 1921, p. 11, fig. 3) and Wikipedia.

Right: Tea-serving Japanese automaton with mechanism (right). 19th century Japan. Tokyo National Science Museum. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

The automaton pictured above is even less like a living thing than a lodestone, or natural magnet. The atoms in a lodestone have an inherent tendency to function together, when they naturally attract things made of iron. By contrast, the parts of an automaton have no built-in tendency to work together. They only do so because they have been artificially arranged that way. Their finality is extrinsic.

In Part One, we discussed the immanent finality which distinguishes natural objects from mere artifacts. By now, the reader may be wondering how Professor Feser distinguishes living things from other natural objects, given that all natural objects possess immanent finality.

According to Feser, living things are characterized by immanent causation i.e. causal processes that begin and remain within the agent itself, and which typically benefit the agent. An example would be the process of digestion, or the mechanical and chemical breakdown of food into smaller components that are more easily absorbed into an animal's bloodstream. This occurs within the animal's body, and it also benefits the animal, as it helps it to stay alive and grow.

In non-living things, by contrast, causation is always directed outward, at an external effect. The example of a magnet picking up a nail illustrates this point. This kind of causation is called transeunt, as opposed to the immanent causation found in living things.

Professor Feser has certainly performed a very valuable service in elucidating, for a modern audience, one of the crucial differences between living and non-living things. However, I do not think that this is the only critical difference between living organisms and other natural objects. Another key difference (which I discuss in Part Three below) is that living things are nested hierarchies, where each level contains several entities at the level below it: very simply, an organism contains organs, which contain cells, which contain molecules, and so on. In these nested hierarchies, the various parts work together for the good of the whole, allowing living things to display "end-directedness", or teleology, in a much stronger sense than other natural objects do.

The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp by Rembrandt van Rijn. 1632. Royal Picture Gallery Mauritshuis, The Hague. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

Corpses constitute a severe problem for Thomistic metaphysics. According to Aquinas, a living human being has one and only one substantial form, the soul, which grounds all of that human being's biological and physicochemical properties. When a human being dies, the soul ceases to inform the body, which then becomes a corpse: a new form (that of a dead body) replaces the old one (the human soul). After death, the soul and the biological and physicochemical properties associated with it no longer remain. Aquinas and modern-day Thomists like Professor Feser hold that the only thing which still remains of the old human being after death is prime matter, which is matter devoid of any form whatsoever, and hence devoid of any positive features. Thus a corpse has absolutely nothing positive in common with the living person whose body it once was.

In my opinion (and that of most medieval philosophers), this position of Aquinas' is a very counter-intuitive notion. Since the only thing remaining after death - prime matter - lacks any positive attributes of its own, it is a profound mystery why a corpse should retain the size and weight of the person whose body it once was, even after that person's death. Why do these positive properties remain? Thomistic metaphysics gives us absolutely no reason to expect that they should.

Professor Feser has repeatedly maintained in his writings that Intelligent Design proponents have a defective view of living things, which renders their argument for an Intelligent Designer who might be God, utterly useless. For Thomists like Feser, a living thing is one thing in a very radical sense. All of its properties - not only at the biological level, but also at the physicochemical level - are grounded in its unique form (which is joined to prime matter), and it is this form (which we call the soul) that explains everything about that living thing. To maintain otherwise, claims Feser, is to fall into the dangerous trap of regarding living things as nothing more than highly elaborate artifacts. Once you view things as artifacts, it becomes impossible in principle to demonstrate that the Intelligent Agent who gave living things their form, also gives them their being - or in other words, maintains them in existence. Since Feser wishes to demonstrate that the Intelligent Agent which guides living things to their ends is also responsible for maintaining them in being - for if the Agent didn't do that, it couldn't be God - he therefore feels that it is his duty, as a Catholic philosopher, to oppose Intelligent Design.

Before we proceed further, I'd like to provide my readers with a handy summary of the philosophical terminology used by St. Thomas Aquinas and by modern-day Thomists, including Professor Feser. Readers are welcome to refer to this summary, when trying to grasp the key points at issue in the philosophical controversy between Feser and Intelligent Design proponents:

|

A Brief Glossary of Metaphysical Terms, According to St. Thomas Aquinas Substance: A thing-in-itself, as distinct from its properties. Angels, human beings, animals, plants and inanimate natural objects are all substances. (God is not a substance; He's in a special category of His own, as we'll see below.) A substance is one thing; thus a mere assemblage of parts is not a substance. Human artifacts are not true substances, as their parts have no inherent tendency to function together. Natural objects (including humans) are substances which are made up of two components: prime matter and substantial form.

Prime Matter: Matter devoid of any form - in other words, pure passive potency. Prime matter is the ultimate substrate of change. It has no positive features, and thus we cannot even conceive of prime matter in its own right. Prime matter can never exist in isolation; it is always realized under some form.

Substantial form: A thing's substantial form is simply that by virtue of which it is the kind of thing it is. For instance, an electron's substantial form is what makes it an electron and not a muon; and a lion's substantial form is what makes it a lion, and not a cheetah. In natural objects, substantial form is an actualization of the prime matter underlying it. Each kind of natural object has one, and only one, substantial form. A living thing's unique substantial form is called its soul. Accident or accidental form: A property of a thing. Aristotle recognized nine kinds of properties, which can be illustrated with the example of a hypothetical individual named John Smith, who is smelly (quality), double the size of his younger brother (relation), in London (place), in the year 2012 (time), standing (position), with a cell phone (possession or habitus), talking on his cell phone (action) and being yelled at by his boss over the telephone (experience undergone by him or "passion", as in the term "passive voice"). Some accidents are essential: if the individual didn't possess them, it would be a different kind of thing. Other accidents are inessential. John Smith would still be human if he wasn't smelly or bigger than his brother, but he wouldn't be human without his capacity to reason. |

|

Essence: The nature of a thing. For natural objects, a thing's essence consists of matter and form. However, God and the angels have no underlying matter; their essence consists of form alone. The essence of finite beings is distinct from their act of existence. God's essence, however, is simply to exist: He is unbounded existence. Because He and He alone is totally unbounded, God doesn't fit into any category we can devise. For instance, God is not a substance as such. A substance is a thing which has existence, whereas God is Existence. Existence: A thing's act of existence, which for Aquinas is distinct from its essence. For Aquinas, the distinction between essence and existence is real, and not merely logical. Aquinas' argument for there being such a distinction is that I can know what a thing is without knowing whether it exists or not. |

|

Act: Any positive realization of an underlying potential. Matter, for instance, may be realized in the form of a banana (a substantial form) and on top of that, as yellow (an accidental form). According to Aquinas, a thing's essence is actualized ("switched on", if youy like) by its act of existence. Potency: Any capacity of a thing to be realized in some way. For example, wax has a potency to melt (and thereby undergo accidental change, as it is still the same chemical substance) as well as potency to burn (a substantial change, which would turn it into a different kind of chemical substance). A potency may be either active (e.g. the [never exercised] power I have to give someone a black eye by punching them in the face), or passive (e.g. the capacity I have to get a black eye if someone punches me in the face instead).

|

As a Thomist, Professor Feser holds that a living thing has one (and only one) substantial form. Not only are all of the biological properties of a living thing grounded in its form, but all of its physical and chemical properties are grounded in this form, too. (More precisely, these properties all inhere in the substance of a living organism, which consists of its form plus its prime matter. Prime matter, however, is absolutely devoid of any properties of its own; it is nothing more than pure passive potency.) Feser also subscribes to a top-down, holistic view of living things: for him, the biological properties of a living thing explain its physicochemical properties, rather than the other way round.

This Thomistic view of living things is an extremely radical one, with the counter-intuitive consequence that when a living thing dies and loses its substantial form, literally nothing positive remains of it in the corpse of the creature that was once alive. Most people would say that the atoms and molecules remain, but Thomists would deny that. On their view, atoms and molecules lose their chemical identities when they are subsumed into the body of a living thing, as occurs in the process of digestion. They simply become parts of a living thing. When that living thing dies, the only thing that remains of it is prime matter, which Thomists define as pure passive potency, with no positive features whatsoever not even a measurable property, such as mass or energy. If this is correct, then it becomes very difficult to explain why the fresh corpse of a man still has the same dimensions and weight as the man did, when he was alive.

The Thomistic view that a living thing has a single and all-embracing substantial form, is of crucial importance for understanding why Feser objects so vehemently to Intelligent Design. He seems to think that ID proponents conceive of living things as artifacts which are built from the bottom up that is, assembled from existing parts which already have substantial forms of their own, and that the new form they acquire when they are assembled together as a living thing must be merely an accidental feature, rather than one that defines its very essence:

[O]rganisms, being natural objects, are not artifacts in the first place, and (therefore) they don't have parts with substantial forms of their own which may or may not have been brought together either by a divine artificer or by impersonal evolutionary processes so as to take on the accidental form of a certain kind of organism (in the way the parts of a watch come together to take on the accidental form of a watch).

Nature versus Art (April 30, 2011).

As a Thomist, Professor Feser is assuming here that any form which is imposed on top of a substantial form can only be an accidental form. As we'll see in Part Three, many medieval philosophers would have stoutly rejected such an assumption. Rather, they believed that a higher-level substantial form could be imposed on top of a lower-level one. These philosophers did not view organisms as artifacts, and neither do Intelligent Design proponents. Feser is simplifying the issue here.

Scholastic disputations, medieval style. The illustration above depicts a meeting of doctors at the University of Paris. From a medieval manuscript of Chants royaux. Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

To hear Professor Feser tell it, you would think that there were only two metaphysical options for thinking about living organisms: either you accept the Thomistic thesis that a living thing is a single entity with a unique substantial form grounding all of its properties, or you become a mechanist, jettison all talk of "forms", and regard a living organism as a mere assemblage of atoms.

While I believe that Intelligent Design is perfectly compatible with the Thomistic view that a living thing has only one substantial form, I would also argue that Professor Feser is guilty of presenting a false dichotomy in contrasting the radically holistic views of St. Thomas Aquinas with the mechanism of modern scientists.

What Feser omits to point out is that there is an intermediate view, which was widely held by theologians in the Middle Ages, which acknowledges both the unity of a living thing, but at the same time treats it as a multi-layered entity, with two or more forms grounding its properties. Some medieval Catholic theologians, who were contemporaries of St. Thomas Aquinas, held that living things are entities with two or more layers of substance, and that a substantial form of corporeity (or "bodiliness") underlies the biological form, or soul, of a living thing. On such a view, we can legitimately speak of a substantial form being "imposed" on a pre-existing body, without in any way prejudicing the biological unity of the living organism created as a result of such an "imposition".

Many medieval philosophers thought that Aquinas' view that a living thing had one and only one substantial form, grounding all of its properties - biological and physicochemical - was a rather odd one, and preferred instead to postulate the existence of two or more forms in a living thing. Thus a form of corporeity (or "bodiliness") was assumed to underlie the biological form of a living thing. On this latter view, a corpse still has the form (and hence the properties) of a body, but it lacks the form of a living body.

The point I want to make here is that even among Catholic philosophers of the Middle Ages, there was a wide diversity of views regarding the nature of living things. Some philosophers agreed with Aquinas that a living thing must have one, and only one, form. A larger number maintained, however, that a living thing possesses two or more forms, and that the soul of a living thing, or the form which makes it alive, sits on top of an underlying form, which grounds its physicochemical properties. If we adopt that way of talking, then it becomes easy to see how the form of a living thing can be imposed on pre-existing material. We don't have to regard living things as artifacts in order to make sense of this picture. All we need to suppose is that the emergent holistic properties of living things, which give them a genuine unity at the biological level, supervene upon the underlying physicochemical properties of the material (i.e. DNA, proteins and other organic molecules) out of which a living thing is composed. This material has no inherent tendency to come together in the first place, but having been assembled together, it does have an inherent tendency to stay together and to function harmoniously as a single, organic entity.

The following table summarizes the key points of disagreement between St. Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274) and certain other Scholastic philosophers, on metaphysical matters. Many of these matters related to living things.

|

Key Areas of disagreement between St. Thomas Aquinas and certain other Scholastics: (1) Some Scholastics held that prime matter, though entirely without form, is actual in some way; thus it is not pure passive potency. For instance, Francisco Suarez (1548-1617) argued that prime matter must have some degree of actuality. Duns Scotus (1265-1308) is believed to have held a similar view. (2) Many Scholastics (including St. Bonaventure and William of Ockham) held that a living thing has at least two substantial forms: an underlying form of corporeity which makes it a body, and an overarching form, the soul, which makes it a living body. (3) Some Scholastics (e.g. Duns Scotus) may have believed in a nested hierarchy of substantial forms, within a living body. Thus each organ in my body has its own substantial form, and each cell in that organ has its own substantial form, and so on, all the way down. (4) Many Scholastics held that angels, unlike God, are not pure forms, but contain some kind of "spiritual matter" in addition to their form. Without this, it was thought, they would be Pure Act, and hence indistinguishable from God. St. Bonaventure (1221-1274) was a notable exponent of this view. (Aquinas' answer was that an angel would still differ from God even if it was a pure form, as it would be a composite of essence and existence - unlike God, Who is pure existence.) (5) Not all Scholastics posited a real distinction between a thing's essence and its existence, as Aquinas did. Some Scholastics (e.g. Duns Scotus and Francisco Suarez) held the distinction to be a purely logical one. (6) Not all Scholastics followed Aquinas in regarding a creature as a composite of potency plus act. From the fact that an entity contains both potency and act in its nature, it does not follow that it is composed of potency plus act. |

A possible objection from Professor Feser

A nine-banded Armadillo in the Green Swamp, central Florida. Courtesy of www.birdphotos.com and Wikipedia.

Some Scholastic philosophers held that a creature such as an armadillo had two substantial forms: one (a form of corporeity) making it a physical body, and another (in this case, the creature's soul) making it an organism of a specific kind - namely, an armadillo. (As most readers will be aware, the soul of an animal was viewed as intimately bound up with its underlying matter.)

As a Thomist, Professor Feser might argue that it is simply absurd to think that one and the same thing could possess two substantial forms, as this would then entail that the question, "What is this thing?" had two contradictory answers: "It is an A" and "It is a B" (e.g. "It is an armadillo" and "It is a bear"). Both answers cannot be right. In reply, I would argue that the two answers need not be contradictory; they may be complementary rather than contradictory. For example, the question, "What is this thing?" may have the answers, "It is an armadillo" and "It is a body", where the term "body" is understood in the context of the laws of physics. (I shall say more about the laws of physics in section 3.6. below.) These two answers complement rather than contradict each other. Thus a biologist, who understands the first answer, can tell me why armadillos are (unlike most other animals) capable of contracting leprosy systemically (due to their unusually low body temperature, which makes them hospitable to the leprosy bacterium), while a physicist, who understands the second answer, can tell me why a tennis ball, when hurled against the hard-plated armor of an armadillo, will not displace the creature very far: the armadillo, being much more massive than a tennis ball, will only acquire a very low velocity after the collision, and the friction of the ground on which the armadillo is standing will soon bring it to a halt.

|

|

Left: Vienne Cathedral, France. The Catholic ecumenical Council of Vienne (1311-1312) held its opening session here in 1311. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

Many Catholics are under the false impression that the Council of Vienne ruled in favor of Aquinas' view (shared by Professor Feser) that living things possessed one and only one substantial form. In fact, it did no such thing. Most of the bishops at the Council believed that a living thing possesses a plurality of forms. All the Council wanted to assert was that the intellectual soul informs the body directly, thereby preserving the unity of man.

Right: The late Baroque facade (completed by Alessandro Galilei in 1735) of St. John Lateran's Basilica, in Rome. The Catholic ecumenical Fifth Lateran Council (1512-1517) held its opening session in this basilica, in 1512. Image courtesy of Jastrow and Wikipedia.

The Fifth Lateran Council reiterated the declaration of the Council of Vienne in 1311 that the human soul exists "essentially as the form of the human body", as well as affirming the soul's immortality and condemning those who denied that different people have different souls. Since the Fifth Lateran Council said nothing further about the notion that a living thing possesses a plurality of forms, and since no subsequent ecumenical Council has said anything about the matter, Catholics are free to think as they wish on the subject.

For the benefit of those Catholic readers who may be wondering, I would like to point out that the ecumenical Council of Vienne (1311-1312) chose to leave the matter of whether living things have only one form or a plurality of forms open for discussion: its declaration that the rational human soul is "of itself and essentially the form of the body" did not rule out the possible existence of other forms underlying the rational soul. Those who wish to learn more can read Fr. Frederick Copleston's A History of Philosophy: Medieval philosophy (Vol II. in the series, Continuum Books, Third edition, London, 2003, p. 452) here. I shall quote a brief passage:

...[I]n 1311 the Council of Vienne condemned as heretical the proposition that the intellectual soul does not inform the body directly (per se) and essentially (essentialiter). The Council did not, however, condemn the doctrine of the plurality of forms and affirm the Thomist view, as some later writers have tried to maintain. The Fathers of the Council, or the majority of them at least, themselves held the doctrine of the plurality of forms. The Council simply wished to preserve the unity of man by affirming that the intellectual soul informs the body directly.

The Fifth Lateran Council (1512-1517) simply reiterated the declaration of the Council of Vienne in 1311 that the human soul exists "of itself and essentially as the form of the human body", as well as affirming the soul's immortality and condemning those who denied that different people have different souls. [Readers should scroll down to view Session 8, on December 19, 1513, to view the relevant decree.]

To this day, the Catholic Church has not pronounced as to whether a living thing has one or multiple substantial forms. Catholics have absolute freedom to think as they please on this issue.

Blessed John Duns Scotus (1265-1308). Unlike St. Thomas Aquinas, Scotus held that a living organism contained a plurality of substantial forms. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

Blessed John Duns Scotus (1265-1308) was one of the most brilliant philosophers of the Middle Ages. His complex and nuanced arguments earned him the nickname of "the Subtle Doctor". Duns Scotus was also a prominent exponent of the common medieval view that each living thing contains a plurality of substantial forms. However, Scotus' precise views on the plurality of forms are the subject of some scholarly debate. The "standard" interpretation of his views can be found in an article by Professor Thomas Williams in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy:

... Scotus holds that some substances have more than one substantial form (Ordinatio 4, d. 11, q. 3, n. 54). This doctrine of the plurality of substantial forms was commonly held among the Franciscans but vigorously disputed by others. We can very easily see the motivation for the view by recalling that a substantial form is supposed to be what makes a given parcel of matter the definite, unique, individual substance that it is. Now suppose, as many medieval thinkers (including Aquinas) did, that the soul is the one and only substantial form of the human being. It would then follow that when a human being dies, and the soul ceases to inform that parcel of matter, what is left is not the same body that existed just before death. For what made it that very body was its substantial form, which (ex hypothesi) is no longer there. When the soul is separated from the body, then, what is left is not a body, but just a parcel of matter arranged corpse-wise. To Scotus and many of his fellow Franciscans it seemed obvious that the corpse of a person is the very same body that existed before death. Moreover, they argued, if the only thing responsible for informing the matter of a human being is the soul, it would seem that (what used to be) the body should immediately dissipate when a person dies. Accordingly, Scotus argues that the human being has at least two substantial forms. There is the "form of the body" (forma corporeitatis) that makes a given parcel of matter to be a definite, unique, individual human body, and the "animating form" or soul, which makes that human body alive. At death, the animating soul ceases to vivify the body, but numerically the same body remains, and the form of the body keeps the matter organized, at least for a while. Since the form of the body is too weak on its own to keep the body in existence indefinitely, however, it gradually decomposes.

(Thomas Williams, John Duns Scotus, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2010 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.).)

On this view, a living thing can contain more than one substantial form, because it is ontologically multi-layered: at its bottom level it is a body, and at its top level it is an organism.

An alternative interpretation of Duns Scotus' views on living organisms

Russian dolls. Each doll is encompassed inside another, until the smallest one is reached. This is the concept of nesting. When this concept is applied to sets, the resulting ordering is called a nested hierarchy. Duns Scotus envisaged an organism as a nested hierarchy, on Assistant Professor Thomas Ward's reading of his views. Image courtesy of Fanghong, Gnomz007 and Wikipedia.

A quite different (and highly original) interpretation of Scotus' views is put forward by Assistant Professor Thomas M. Ward, of Loyola Marymount University, in his forthcoming essay, Animals, Animal Parts, and Hylomorphism: John Duns Scotus's Pluralism about Substantial Form, soon to appear in the Journal of the History of Philosophy. Whereas on the "standard" interpretation of Duns Scotus, living things are ontologically multi-layered entities (bodies overlain by an organismic form), on Ward's interpretation, living things are nested hierarchies, where each level contains the levels below it. The body contains organs, which contain organelles, which contain cells, which contain molecules, and so on. According to Ward, Scotus held that each organ in the body (as well as each of the constituent parts of an organ, or what we might call organelles) has its own substantial form, and that whenever Scotus discussed the "form of corporeity" of a living thing in his writings, he really meant it as a convenient short-hand for the whole set of the nested substantial forms in a living thing, with the exception of the soul, which sits on top and which makes a living thing one thing at a holistic level. As Ward puts it:

Scotus and others in the medieval period call matter and substantial form the essential parts of a substance. Scotus is also a pluralist about substantial forms: he thinks that living composite substances are composed of matter and more than one substantial form. According to the common scholarly view these substantial forms are a soul and a form of corporeity, where the form of corporeity is supposed to be the substantial form by which an animal is corporeal, and the soul is supposed to be the substantial form by which an animal is living. Fewer commentators have recognized that Scotus also thinks that what he and others call the integral parts of animals, things like livers and hearts, are themselves composites of matter and distinct kinds of substantial forms, a form of the liver, a form of the heart, and so on.... I argue that... Scotus thinks that in a process of embryological development many substances are generated a heart, blood, a brain, and all the rest of the organs and under natural conditions these substances can be informed by a soul. The union of these substances with the soul is the last stage in the generation of a complete organism, whereby these substances become integral parts of one animal. For Scotus there is no substantial form of corporeity whose job it is to make a substance merely corporeal. (pp. 1-2)

As I am not a specialist in medieval philosophy, I have no wish to adjudicate the current scholarly controversy concerning Duns Scotus' views on the soul. All I want to point out here is that Scotus' view is strikingly different to that of St. Thomas Aquinas, and that it seems to me that Scotus' view could accommodate talk of a substantial form being "imposed" on a pre-existing body, without in any way prejudicing the biological unity of the living organism created as a result of such an "imposition".